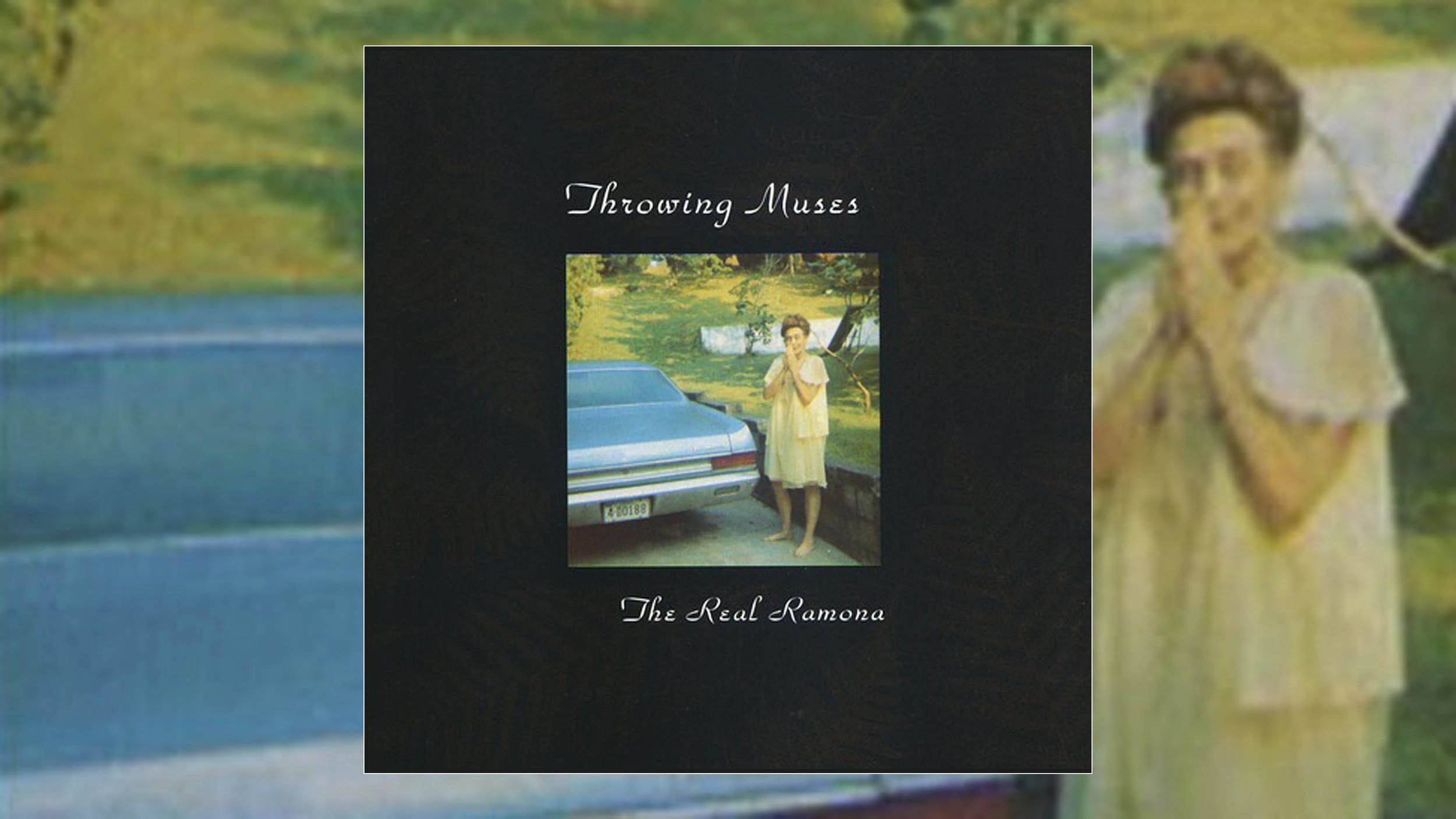

Happy 35th Anniversary to Throwing Muses’ fourth studio album The Real Ramona, originally released in the UK February 18, 1991 and in the US March 12, 1991.

When she was 16 years old, Kristin Hersh was dashing to her summer job on her bike when an old woman in a speeding Chevy hit her with full force. Hersh remembers soaring through the air in slow motion and, as the pavement inched closer, she seemed to levitate over the asphalt, tree branches swaying in the breeze and the smell of fresh-cut grass sweetening the air. A thought entered her mind: “Go limp.” And so she did, knowing that she was about to hit her head harder than she’d ever hit it before.

The old woman sped off—a hit and run. When a neighbor raced out of her house to see if the teenager splayed in the middle of the street was still alive, Hersh caught a glimpse of her bloody face, shredded horrifically like hamburger, in the woman’s mirrored sunglasses. Hersh would come to believe that the old woman in the Chevy, the hit-and-run lady, was a witch of the spell-casting kind. A few days later, lying in a hospital bed with a double concussion, Hersh was plagued by sounds—industrial grating noise, metallic humming, tinkling wind chimes, and the lapping of the ocean that came together to form a song. A constant thrum of new songs would become her new normal, like a strange curse.

She’d seen songs in color—a condition known as synesthesia—ever since her father, a hippie college professor known to everyone as Dude, had taught her to play guitar when she was a young child. But this was different. Now she felt almost possessed with a compulsion to write songs all the time, so much so that she’d have to swim every night just to burn off all the excess, frenetic energy.

When they were fourteen, Hersh and her stepsister Tanya Donelly had decided to start a band. Hersh and Donelly were born three weeks and 900 miles apart in the summer of 1966, but they met in the third grade after Hersh’s family moved from Georgia to Rhode Island, where Dude had taken a job at Salve Regina University. They became stepsisters at 11 after introducing their divorced parents to each other. Petite with dishwater-blond hair, they looked uncannily alike, and they loved practicing Beatles songs together on their guitars. “Are you twins?” people would ask. “We’re step-twins,” Donelly would reply, and folks would nod as if this made complete sense.

They began as an all-female band called Throwing Muses, recruiting Elaine Adamedes and Becca Blumen, fellow classmates at Rogers High School in Providence. Adamedes and Blumen were later replaced by bassist Leslie Langston and drummer David Narcizo and, in 1984, the band recorded a self-titled EP that they released on their own label. Then, around the time Hersh turned 18, she began living in an apartment in Providence she nicknamed the “Doghouse,” where she wrote feverishly and uninterrupted.

“Last fall, the music I heard began to feed off the Doghouse’s evil energy,” Hersh recounts in Rat Girl, a memoir based in part on the diary she kept when she was 18, only two years after her fateful bike crash. “Songs no longer tapped me on the shoulder; they slugged me in the jaw. Instead of singing to me, they screamed, burrowing into my brain as electricity. I got zapped so bad in that apartment, I don’t think I’ll ever rest again.” Still, she was proud of them, despite what they took out of her: “I’m actually head over heels in love with these evil songs, in spite of myself. It’s hard not to be. They’re … arresting.”

Hersh’s fiery Doghouse sessions and her increasing inability to turn off her musical brain led to a suicide attempt, followed by a diagnosis of schizophrenia that was soon amended to a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. She began taking lithium, until she discovered she was pregnant at the age of 19 and quit for the health of the baby. Still, despite these major shakeups in Hersh’s life, Throwing Muses relocated to Boston that year, deciding it was now or never to get serious about making something of their band and Hersh’s arresting songs.

Listen to the Album & Watch the Official Videos:

The songs the band recorded would soon become known as the “Doghouse Demo,” which they shared with Gary Smith, a producer at Ford Apache Studios, upon moving to Boston in 1985. Smith became a tireless champion of Throwing Muses (and was beloved by many other Boston bands), sending out their demo far and wide. The tape eventually attracted the attention of Ivo Watts-Russell, co-founder of the 4AD record label in the UK. Hersh and Watts-Russell struck up a long-distance friendship over the phone, and based on that chatty alliance Throwing Muses became the first American band to be signed to 4AD, eventually paving the way for fellow Boston band the Pixies to also be signed. Thanks to 4AD, the two bands would become huge in England and throughout Europe long before fans in America caught on.

Throwing Muses recorded their first full-length album, their eponymous debut, with producer Gil Norton, prior to Hersh giving birth to her first child, a little boy named Dylan. They released two more albums—1988’s House Tornado and 1989’s Hunkpapa—and then Leslie Langston left the band in 1989 and was replaced by Fred Abong.

In 1991, the band released their most pop-leaning record to date. It was perfect timing—the same year Nirvana exploded in the mainstream with Nevermind—and Throwing Muses’ contribution, The Real Ramona, would end up becoming one of a handful of seminal albums to form the backbone of ’90s “alternative,” as the college rock/modern rock genre soon came to be known. (“They call us ‘alternative’ rock. We think it’s disparaging,” Hersh complains to a friend in Rat Girl. “I mean, alternative to what, real rock?”)

Tanya Donelly, who had already dabbled in a side project by forming the Breeders and recording Pod (1990) with the Pixies’ Kim Deal, would end up leaving Throwing Muses to form Belly, another ’90s-alternative behemoth, after recording The Real Ramona. Around the same time, Hersh began a solo career, releasing Hips and Makers, before eventually recording additional Throwing Muses material. Still, despite going their separate ways, The Real Ramona would serve as a foundational document of both Hersh’s and Donelly’s careers, with songs like “Counting Backwards” and the Donelly-penned “Not Too Soon” serving as beloved blueprints of the ’90s alternative canon.

The Los Angeles Times seemed to sense the coming excitement in 1991, and published a lengthy profile of Throwing Muses around the release of The Real Ramona. By that point, Hersh and the band had been contending with more difficulties. Hersh had just gone through a long custody battle with the father of her then five-year-old son Dylan and had lost primary custody, in part due to the travel demands of being a musician. Meanwhile, the band had split ways with their manager Ken Goes in yet another court battle. “There was so much going on at the time. It was probably the worst that ever happened to me,” Hersh divulged. “I didn’t remember why I was in the band.”

Still, working on The Real Ramona ended up being healing, and invigorating. “The project itself took me out [of personal problems] in a good way,” Hersh explained. “Hard work is good for it—hard work with meaning behind it.”

The Real Ramona kicks off with an inaugural drum fill by David Narcizo and then a wholly infectious groove. “Counting backwards, I count you in,” Hersh sings with her charming signature rasp, and then come some beautiful harmonies between Hersh and Donelly, their voices melding seamlessly and then coming apart again. “Him Dancing” serves a refreshing role reversal from the conventional pop song, with man as subject and woman as possessor of the gaze—“Him dancing / Him rolling on the ground / Him moaning ‘I can’t help myself.’” There’s more decisive drumming by Narcizo here, and the beat provides the sturdy structure Hersh’s voice weaves in and out of, tickling its bones.

“Red Shoes” harkens back to the not-so-distant ’80s, with unmistakable Kate Bush influences (though Bush’s own “The Red Shoes” wouldn’t come out for another couple years). It’s sexy and slinky with feathery guitars and Hersh’s slightly ragged wails—a slow and tasteful striptease.

“Graffiti,” my favorite track on the album, is ticking and urgent and hauntingly sad. I listened to this album a lot in college when I was going through a breakup that spanned summers and continents and, for whatever reason, it hit the right register of melancholy so the fact that its lyrics were cryptic didn’t matter at all: “See my name on the wall / I tried to walk on this wall / It fell right under my feet.”

The mood picks up with “Golden Thing,” raucous and vintage-sounding with Hersh and Donelly singing in unison like the Chordettes, “You gotta see this / Golden thing / You golden thing.” If you don’t immediately crawl out of your funk and shimmy and hustle around the room to this one, there’s something very wrong. Meanwhile, “Ellen West” is strutting and slightly dangerous, like walking down a dark street in the wrong neighborhood against a backdrop of jagged, zigzagging guitar riffs and urgent drumbeats.

“Dylan,” clearly named after Hersh’s son, is sparse and spidery and sad, an instrumental with only the faint calls of what sound like ghosts. “Hook in Her Head,” another favorite of mine, begins one way and abruptly changes shape at the second verse, becoming several different shifting songs in one. It’s a song like those I imagine plaguing Hersh in the Doghouse—wild and intricately structured, but also multicolored and sublime.

The album takes a sharp turn with “Not Too Soon,” a ’60s girl group-inspired confection with swirling guitars and fun, flirty vocals that alternate between husky-whispery and bratty in the most endearing way. “Honeychain” takes us into more introspective, melancholy territory with spare guitar and fluttery vocals by Donelly until it suddenly takes a banshee turn before mellowing into a swaying pop song that dissolves into gorgeous two-part harmonies between Hersh and Donelly.

“Say Goodbye” begins with recorded voices off the TV or radio, followed by a chugging melody and Hersh’s slightly snarling vocals. This is another song with esoteric ’80s DNA, one slightly reminiscent of the B-52’s. The album ends with the waltzing “Two Step,” with weeping guitars and diaphanous vocals worthy of a cool and slightly weird prom song.

Eventually, after many years of misdiagnoses, Hersh discovered the true root of her mental-health issues: dissociative disorder, caused by PTSD from childhood trauma. The result was a split personality, one where an entity Hersh referred to as Rat Girl (who emerged after the bike accident) wrote and performed the music, and Hersh herself would disappear. “I had really bad stage fright because I never knew what was going to happen on stage,” Hersh said in 2019. “Kristin couldn’t play guitar. Kristin had no idea what those pedals did. I was just this nice lady, and I’d be doing deals with God in the dressing room.” With the help of therapy, Hersh was able to integrate Rat Girl into her own personality, and the process of making and performing music has since become much smoother and a lot less feverish and anxiety producing.

But in 1991, when talking to the Los Angeles Times about The Real Ramona, Hersh became almost mystical when talking about her songs, describing them as something that originated beyond her. “I was definitely obsessed with songs, because they seemed so huge and I seemed to get smaller in relation to them. I just wasn’t there a lot of the time. The songs were there instead. I thought maybe in order to tell the truth, you have to give up your life.”

Still, she felt that songwriting should go beyond the artist in order to capture something much bigger and more universal: “It’s the difference between telling a dream to someone and fascinating them, and telling them a dream and boring them to tears.”

Listen: