Happy 30th Anniversary to The Juliana Hatfield Three’s debut (and only) album Become What You Are, originally released August 3, 1993.

In 1993, Juliana Hatfield was sitting in a hotel room watching the tail end of Guns N’ Roses’ “November Rain” on MTV. Anyone who was alive at the time remembers how omnipresent that video was, how melodramatic in its rain-soaked, nine-minute depiction of the bad romance between Axl Rose and a Victoria’s Secret model in a mullet wedding dress. As the video wound to its tragic conclusion, hitting its final wailing note as Stephanie Seymour lay “dead” in a coffin, Hatfield’s own video for “My Sister” suddenly came on.

It was a surreal moment. After all, Guns N’ Roses were rock legends—the biggest band in the world. “Had I earned my place on the charts next to G N’ R?” Hatfield worried. Because here was the truth about G N’ R: “You knew that they knew that rock-n-roll stardom was their birthright, that they fuckin’ deserved to be rock stars,” Hatfield recalls in her 2008 memoir When I Grow Up. And now, as evidenced by its MTV “Buzz Bin” distinction, Hatfield’s “My Sister” was elbowing against G N’ R for relevance. Crazy, considering that it didn’t even have a chorus!

“My Sister” is the centerpiece of The Juliana Hatfield Three’s 1993 Nietzschean-titled debut Become What You Are. A mix of grunge, punk, and melodic indie-pop, it’s a left-of-mainstream album that critiques celebrity, the fashion industry, and all things vapid and showy (like Guns N’ Roses), while bravely exploring personal battles with depression, eating disorders, and the general malaise of being a young person out of step with conformist society. “My Sister” embodies some of Become What You Are’s themes by telling the story of a girl enthralled by her cool older sister, who takes her to see the Violent Femmes and the Del Fuegos but who, at other times, is rejecting and aloof.

“I hate my sister, she’s such a bitch,” Hatfield sings in her charmingly girlish voice, countering it later with “I love my sister, she’s the best.” In many ways, the song can be interpreted as not just about a sister, but the sisterhood at a time when feminism was just entering its Third Wave (Hatfield famously—maybe infamously—bristled at the ’90s’ ubiquitous “Women In Rock” label, viewing it as marginalizing). In fact, the most interesting thing about “My Sister” is that Hatfield didn’t have a sister, but instead based the song on her older brother’s onetime girlfriend, whom Hatfield refers to as “Maggie” in her memoir. Maggie introduced a teenage Juliana to underground music and acted as a confidant during a volatile time in Hatfield’s home life. “If I had had a sister, she would have done all the things that Maggie, my adopted, temporary sister, had done for me,” Hatfield writes.

I didn’t have a sister either, but “My Sister” was relatable. My “Maggie” came into my life around 1985 or ’86, when I was around nine years old. Every day after school, my brother and I would trudge over to our babysitter Debi’s house, to deter us from running wild with all the latchkey kids on our American army base in Cold War Germany. Debi had a teenage daughter named Shelli, who was a cool combination of blonde prom queen and ’80s alternative chick. On many an afternoon, I’d sit at the edge of the bathtub while Shelli primped in front of the government-issue mirror, teaching me how to curl my bangs into a cresting wave and line my eyes with blue Cover Girl eyeliner.

More importantly, though, Shelli introduced me to The Smiths. One day, we sat cross-legged on the living-room floor while Shelli played Meat Is Murder (1985) on the record player and I studied the album cover with its photo of a beleaguered American soldier in Vietnam. On the title song, Morrissey’s voice floats between grinding chainsaws and the mooing of anxious cows. “The Smiths are, like, vegetarians,” Shelli explained. I hadn’t read Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle or heard the term “Military-Industrial Complex” yet, but those two concepts came together for me that afternoon, and it felt like Shelli and I were sharing a thrilling little secret. A couple years later, I’d declare myself a vegetarian, and Shelli’s introduction to alternative music would guide my tastes throughout my teen years and beyond.

Many people have a memory like this, of an older sibling or a hip older kid who makes you feel seen while opening your mind to new music and ideas. It’s both commonplace and utterly magical, and Hatfield managed to capture its alchemy with “My Sister.” The song also skillfully tapped into the Gen-X zeitgeist of “Teen Spirit,” with Hatfield examining the intoxicating, formative teenage years from the perspective of a privileged insider (at one of the coolest all-ages shows) and from an ironic, outsider type of remove.

Listen to the Album:

It didn’t escape Nirvana’s notice. “Juliana, I really like your new album, especially ‘My Sister.’ The video’s great as well,” Kurt Cobain told Hatfield in a handwritten note that year. (In a comic twist of coincidence, Nirvana and Guns N’ Roses had an ongoing beef, based on their bands’ stark philosophical differences, that reached its zenith at the 1992 VMAs, the year of “November Rain.” Stephanie Seymour snidely asked Courtney Love if she was a model, Love asked Seymour if she was a brain surgeon, and Axl told Kurt, “Shut your bitch up or I’m taking you down to the pavement.”)

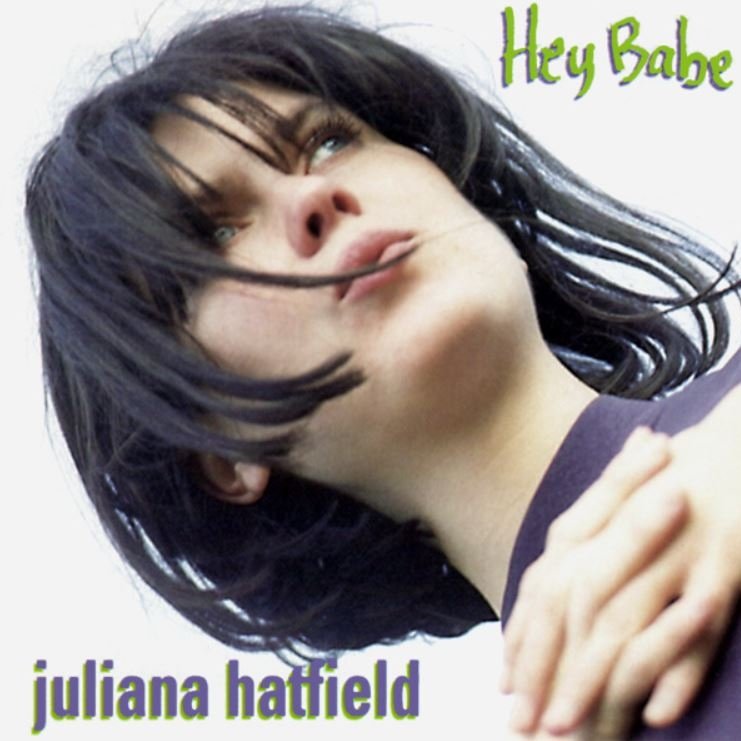

On “Supermodel,” the grungy opening track to Become What You Are, Hatfield sings, “The highest-paid piece of ass / You know it’s not gonna last / Those magazines end up in the trash.” (But then she vulnerably adds, “I wish she'd trade places with me.”) As her star rose throughout the early ’90s, Hatfield’s own pretty face would appear on the cover of Sassy, as well as SPIN. “How long can she make a perfectly healthy audience believe in—and sing along with—a chorus hook as ridiculous as ‘I’m ugly / With a capital U,’” SPIN asked in a 1994 profile, referring to the song “Ugly” on Hatfield’s previous album Hey Babe (1992).

Which means Hatfield wasn’t exactly new to this music thing. In the late ’80s, upon meeting John Strohm and Freda Love at Boston’s Berklee College of Music, the trio formed the Blake Babies and released four albums. Evan Dando, who performed on a couple of Blake Babies’ later albums, then recruited Hatfield to play bass and sing backup on the Lemonheads’ acclaimed 1992 album It’s A Shame About Ray. That same year, Hatfield released her debut solo album Hey Babe.

Hatfield wasn’t a fan of the intense attention that came with a solo career. (One topic of relentless, rather sexist scrutiny was whether or not she and Dando were dating). “I wasn’t very good at navigating the world of people and I think I was struggling with a lot of insecurities and fear,” she divulges. So for her next album, she recruited bassist Dean Fisher and drummer Todd Phillips to form the Juliana Hatfield Three. The band had a fantastic, palpable chemistry, and Hatfield’s best-known songs come from this era. The trio recorded Become What You Are in LA, and, right before going into the studio, Hatfield thought that it needed one more song, something that would shake things up a bit.

She’d been listening to PJ Harvey’s Dry (1992) and was impressed by Harvey’s use of 5/4 time on a couple of songs. So Hatfield sat down to write her own odd-metered song, christening it “Spin The Bottle.” “I challenged myself to do what PJ Harvey had: to write a catchy, driving, danceable pop song in a weird, unpopular time signature,” she recalls. “I wanted people to dance and sing along even though the song was in five.”

Not long after Become What You Are came out, Hatfield was approached about contributing “Spin The Bottle” to the 1994 movie Reality Bites. “I remember reading the script and thinking, ‘Yeah, I would love to have my song in this Generation X movie,’” she recalls. “I don’t know if the term ‘Generation X’ had even been invented yet, but it became kind of this touchstone movie for Generation X issues.” The movie revolved around a group of twentysomethings navigating the AIDS crisis, dealing with dysfunctional parents, coming out as gay, and attempting to put their unique stamp on a culture that was becoming increasingly corporate and mainstream. In fact, the main conflict arrives when Winona Ryder’s character sells her documentary to an MTV-like channel, which then turns her labor of love into cheesy Real World-style programming.

Another amazing opportunity soon arrived when ABC contacted Hatfield about writing a song for My So-Called Life’s Christmas episode. Because MSCL hadn’t aired yet, Hatfield was sent the first few episodes on video. “I watched them and I was like, ‘This is totally great.’ […] It seemed special, different,” she says. “And I really related to the character Angela—she reminded me of myself in high school.” Initially, the offer was simply for Hatfield to write a song, but then after meeting her, MSCL offered her the role of an angel who watches over Ricky after he’s been kicked out of his house for coming out as gay.

Like Reality Bites, My So-Called Life became a ’90s touchstone, this time for teen Gen X and their Boomer parents. It was an antidote to superficial shows like Beverly Hills, 90210, featuring real-looking kids with real-life problems. Sadly, MSCL was cancelled after only one season. In an article titled “Too Bad About ‘My So-Called Life,’ It’s A Fine Family Drama,” critic Joyce Millman observed that it "evokes the emotional turbulence of adolescence with breathtaking accuracy,” adding that the show has an interesting perspective on “midlife crisis and marital boredom.” Millman concluded, “With bittersweet clarity, My So-Called Life shows us that teen angst is something we never outgrow.”

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about Juliana Hatfield:

Hatfield also always manages to capture this truth and Become What You Are does so with particular shrewdness and sensitivity. One of the opening songs, “This Is The Sound,” captures the awkwardness of an unrequited crush, while also embodying the album’s greater philosophical theme. “This is the sound of a tree falling down,” Hatfield sings, asserting that although her concerns might be personal, and maybe trivial in the grand scheme, they do indeed matter and deserve to be heard.

“For The Birds” sees its narrator finding a dying bird on the sidewalk, which sparks a mediation on human cruelty and environmental destruction and then, at song’s end, a lament for the protagonist’s own school-cafeteria plight: “I’m lying if I say I’m cool / ’Cause really I’m not.” Instead of coming across as self-absorbed, the line serves as just one more thing the narrator has no control over—a sad reminder of how small and powerless each of us truly are.

The next track, “Mabel,” examines mental illness and homelessness from a place of compassion, drawing inspiration from the 1974 Cassavetes film A Woman Under the Influence. The song alternates between a son worried about his mother, and passersby who sing, “Check out that lady / She’s talking to herself.” The story ends, sadly, with “Check out that lady / They’re taking her away.”

The album continues its unflinching look at reality with stormy rocker “Dame With A Rod,” a Thelma & Louise-type vengeance fantasy against a rapist—“Touch her again and you’re dead / You heard what I said,” Hatfield warns. Meanwhile, “Addicted” juxtaposes sonic sunniness with dark lyrics about, yes, addiction, but more likely an eating disorder, which Hatfield has been candid about suffering from, most recently via her Substack that features excerpts from an unpublished memoir about her time in an eating-disorder clinic. “My body is a shell / A broken empty shell / A little private hell,” she sings, only to lament later, “The skeleton trees / Remind me of me.”

“Feelin’ Massachusetts” shifts the lament, capturing the listlessness of living in a small town. It eventually rocks into a discordant Lemonheads bop, capturing some of that ‘baby-I’m-bored’ from It’s A Shame About Ray. Next up, “Spin The Bottle,” with its off-kilter twirl, is genius in that it’s about something everyone can relate to—a teenage party game—but also unconventional in its story about meeting a C-List movie star in a bar. Its quirkiness made it a perfect match for Reality Bites, and Ben Stiller even shot the music video, which stars Ethan Hawke, Janeane Garofalo, and Steve Zahn in the bottle-spinning scenes.

“President Garfield” begins as a slow, melancholy stream-of-consciousness track in the style of Liz Phair before it morphs into darker, sludgier rock. The narrator watches a truck go by, then starts thinking about a book some guy wrote about himself that sits on her shelf. The guy has a “neck like a tire, iron man,” and the song is rumored to be a thinly-veiled dig at Henry Rollins (whose real surname is Garfield).

It’s no surprise that Phair, another “Women In Rock” contender and critic, considered Hatfield a kindred spirit. “Juliana’s a great song maker,” Phair told Rolling Stone in 1994. “I think the personality she presents is what bugs people. I have the same problems. When all these women suddenly show up in the media, and we’re having to grapple with the whole of women’s personalities instead of the half of objectification […] people come down way too hard.”

On the hard-driving “I Got No Idols,” the final song on Become What You Are, Hatfield makes no apologies for being who she is—and for not explaining herself. “But I’m a liar, that’s the truth / Go home and think it through,” she sings. “That’s the harm in mystery, all you know is what you see.”

While Hatfield was instrumental in ushering in a rawer and more realistic phase in ’90s music and pop culture, she also became a casualty of its inevitable backlash. Mid-decade, President Clinton signed the Telecommunications Act of 1996, which had a possibly unintended—but wholly unfortunate—effect. “Since Congress passed the Telecommunications Act of 1996, which removed barriers to the number of radio stations one media conglomerate could own, the largest of these conglomerates—Texas-based Clear Channel—has grabbed more than 1,200 stations and shaped a musical mix characterized by the homogenization of playlists, the death of programming diversity, less local programming, reduced public access to the airwaves and rapidly declining public satisfaction with radio and the music it plays,” observed John Nichols of The Nation.

In other words, alternative artists like Hatfield were getting kicked off the airwaves in favor of more sleekly packaged bands—a repeat of Guns N’ Roses’ heyday. But for Hatfield, it was a little more complicated. “A series of outside forces, along with my own ambivalence, conspired to help slow the upward trajectory of my career in the mid-1990s,” she recalls. Around the same time the Act was signed, Hatfield had to cancel a European tour in order to address a serious bout of clinical depression. Prior to that, Danny Goldberg, who had tirelessly championed alternative artists like Hatfield at Atlantic Records (and, famously, had managed Nirvana), left the label. Hatfield left the label soon thereafter. “Maybe the Telecommunications Act of 1996 was a blessing in disguise,” she writes.

Hatfield was unable to maintain the dizzying momentum that came with the release of Become What You Are. However, despite her more low-key profile, she’s been incredibly prolific over the decades, releasing nearly 20 solo albums in addition to collaborations (including a reunion with the Juliana Hatfield Three in 2015). Her unique sound and distinctive worldview have continued to deepen and mature, and with each new album, she becomes what she already is.

Listen: