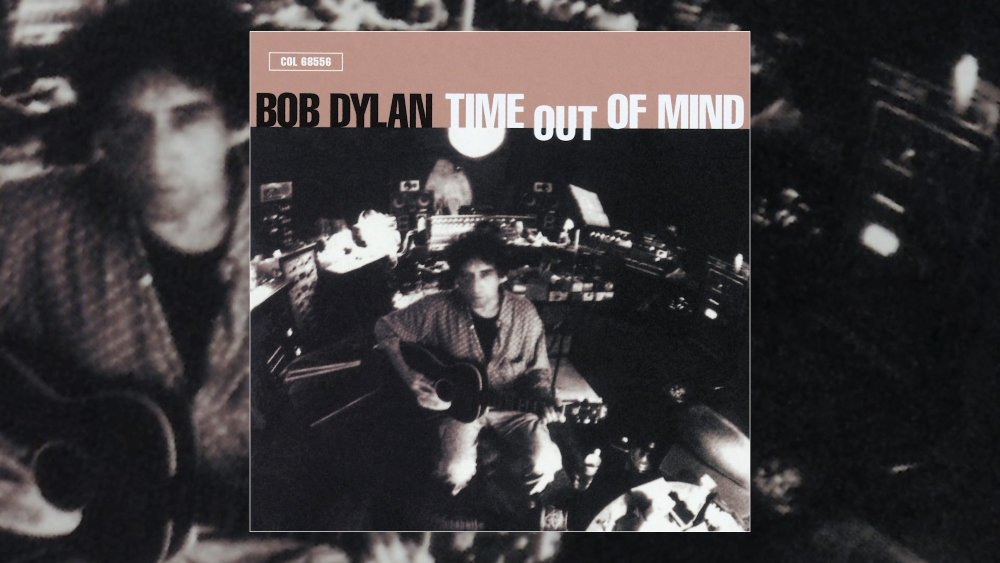

Happy 25th Anniversary to Bob Dylan’s thirtieth studio album Time Out of Mind, originally released September 30, 1997.

When you say an artist has released his best work in 22 years, you’re implying at least three things. First, the artist has an established history of creating good to great music. Second, after creating said good to great music, the artist has enough talent and ability to create more music of comparable quality more than two decades later. Third, the artist has been making notable music for, at the very least, over two decades.

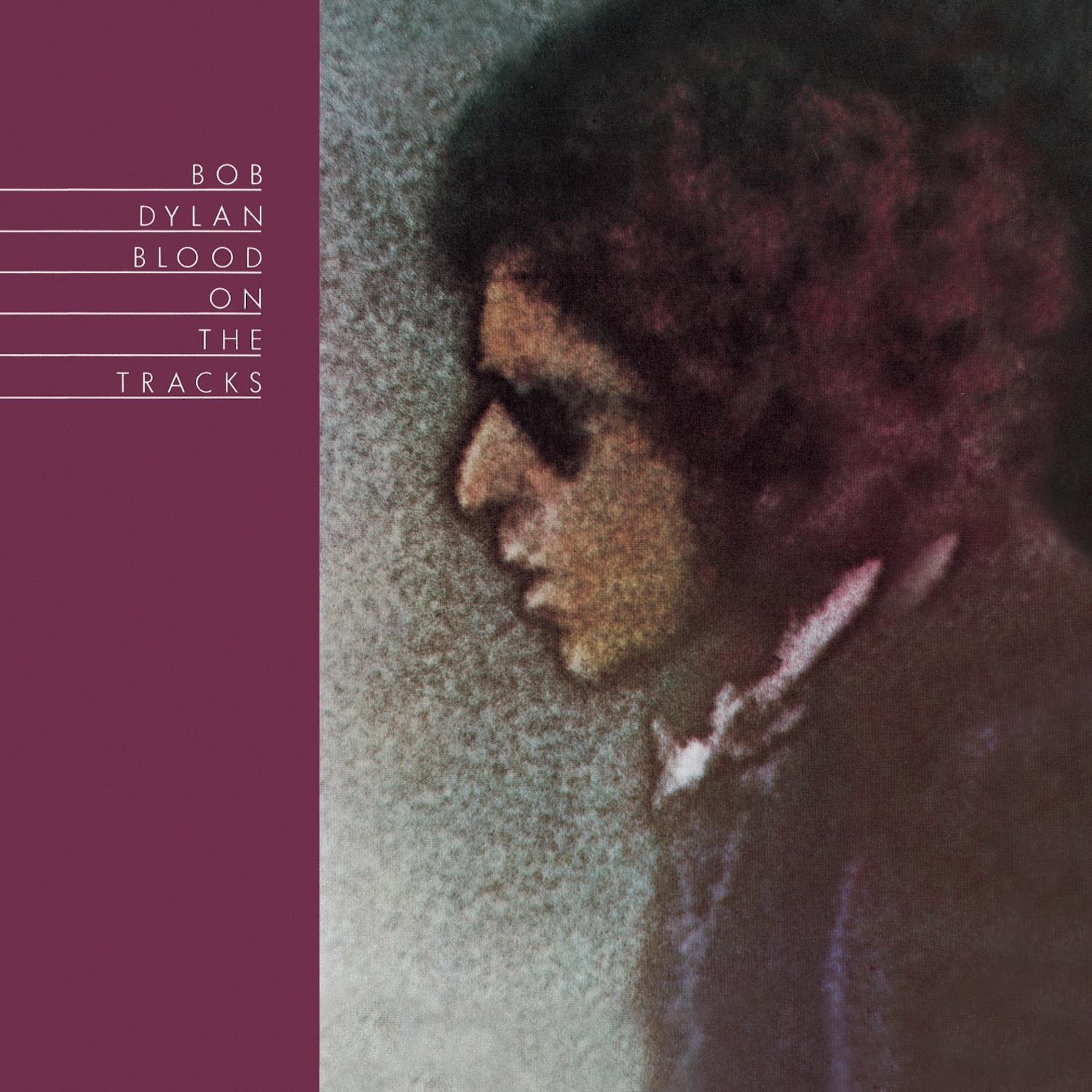

Now, consider that Bob Dylan released Time Out of Mind about 35 and a half years after putting out his revolutionary first album. Then consider that Time Out of Mind is not only arguably his best album since 1975’s groundbreaking opus Blood on the Tracks, but also stands shoulder to shoulder with the best of his catalogue. These factors are all part of what makes Times Out of Mind a remarkable album, as we now celebrate the 25th anniversary of its release.

Time Out of Mind, Dylan’s 30th (30!) solo album, ended what had been a bumpy period for the beyond iconic musician. The future Nobel Prize-winning laureate was in a bit of an artistic funk for a good chunk of the ’80s, releasing Knocked Out Loaded and Down in the Groove to scant commercial success and withering critical reviews. He bounced back with Oh Mercy in 1988, only to follow it up in 1990 with Under the Red Sky, spurned for its over-slick production and almost childish subject matter.

Dylan spent the first half of the 1990s rededicating himself to his roots, releasing two albums of traditional folk songs (Good as I Been to You and World Gone Wrong). In 1995, he released a live album from his legendary MTV: Unplugged performance, which found him acoustically replaying his old classics, infusing them with new meaning. Time Out of Mind was Dylan’s first album of original material in seven years, and with it he started yet another act of his already legendary career.

To record Time Out of Mind, Dylan re-enlisted Daniel Lanois, who had produced Oh Mercy. The Canadian producer was best known for his work with U2, contributing to The Joshua Tree (1987), Achtung Baby (1991), and The Unforgettable Fire (1984), as well as producing Emmylou Harris’ Wrecking Ball (1995). What resulted in their second pairing was not only an album that was better than Oh Mercy, but better than many of the rock albums released in the decade that preceded it.

Dylan and Lanois had notably different production styles. Dylan liked to do most of the work while he was in the studio recording the music. He and his band would play a take, and if the take didn’t work, they’d play it again. Meanwhile, Lanois was a big fan of using studio magic, and liked to make full use of the resources and production technology that was available to him. He had Dylan demo songs before they recorded them, then later did more production work after the songs were recorded. He used separate and specialized microphones for each instrument. He apparently recorded as many as three live drummers during one recording session. And as a result of their differing in-studios ethics, Dylan and Lanois clashed frequently throughout the making of Time Out of Mind.

Watch the Official Videos (Playlist):

Due in large part to Lanois’ methods, Time Out of Mind sounds dense, layered, and dark. It’s also over-produced at times; on a few tracks, the music overpowers the vocals and lyrics. And if you’re listening to a Bob Dylan album, much of the appeal is listening to the lyrics.

Regardless, out of this weird mix of styles and strong personalities, a great album emerged. Time Out of Mind is an artistic triumph, and a critical and commercial success. It earned three Grammy awards, including one for Album of the Year. Maybe the clash of styles helped the album achieve its success, or maybe Lanois’ techniques lent themselves to the album’s overall themes.

The overall theme of Time Out of Mind is the loss of love. It explores the regret, isolation, and lack of direction that can come from a broken heart. Songs touch on how when it comes to love, time does not necessarily heal all wounds, and grief often festers with age. The album is one of the better and most poignant collections of songs about the sadness and pain that love can bring ever recorded.

Things begin with “Love Sick,” a contemplative ode to the misery that lost love can bring. The song begins with sparse keys, backed by muted strings, bassline, and guitar. Dylan sings, “Did I hear someone tell a lie? / Did I hear someone’s distant cry? / I spoke like a child; you destroyed me with a smile / While I was sleeping.” The guitars build with power and volume as Dylan adds, “I’m sick of love but I’m in the thick of it / This kind of love I’m so sick of it.”

Much of Time Out of Mind continues in this vein, with songs like “Standing in the Doorway” and “Not Dark Yet,” where Dylan reflects on feelings of abandonment and the hopelessness that goes along with it. The album sports distinct blues influences, in both sound and lyrics, especially on tracks like “A Million Miles” and “’Til I Fell in Love with You.” On the face of it, the over-production on these songs is a somewhat odd choice because the Blues is known for its spare minimalism. But, again, Dylan and Lanois make the alchemy work.

Lyrically, Dylan is effective as ever by saying a lot when not using that many words. On “’Til I Fell in Love with You,” he expresses the anguish that rattles around in his head as he tries to recover from a break-up, attempting yet failing to move past it, singing, “Junk is piling up, taking up space / My eyes feel like they’re falling off my face / Sweat falling down, I’m staring at the floor / I’m thinking about that girl who won’t be back no more.”

Time Out of Mind peaks with “Trying to Get to Heaven,” a sharp and introspective exploration of learning to cope with loss. Dylan goes on a metaphorical journey around America’s heartland, working to distract himself from the pain of rejection, trying to convince himself that he’s getting over who he once considered his true love. During the early verses he muses, “Every day your memory grows dimmer / It doesn’t haunt me like it did before” and “You broke a heart that loved you / Now you can seal up the book and not write anymore.” But as the song progresses, he allows his sorrow to creep in, singing, “They tell me everything is gonna be all right / But I don’t know what ‘all right’ even means” and “When you think that you’ve lost everything / You find out you can always lose a little more.” The song also features two beautiful harmonica solos by Dylan, the only time he utilizes the instrument throughout the entire album.

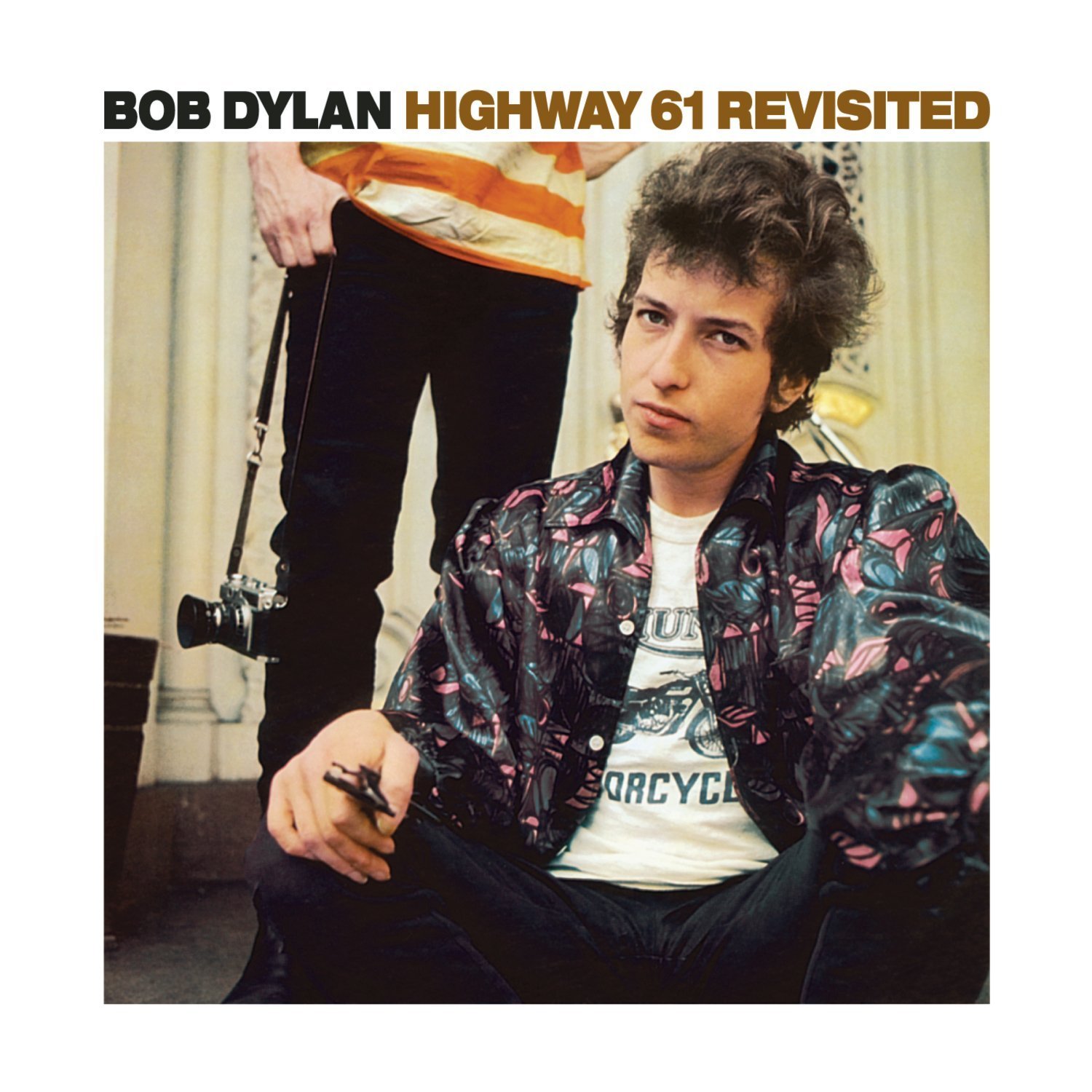

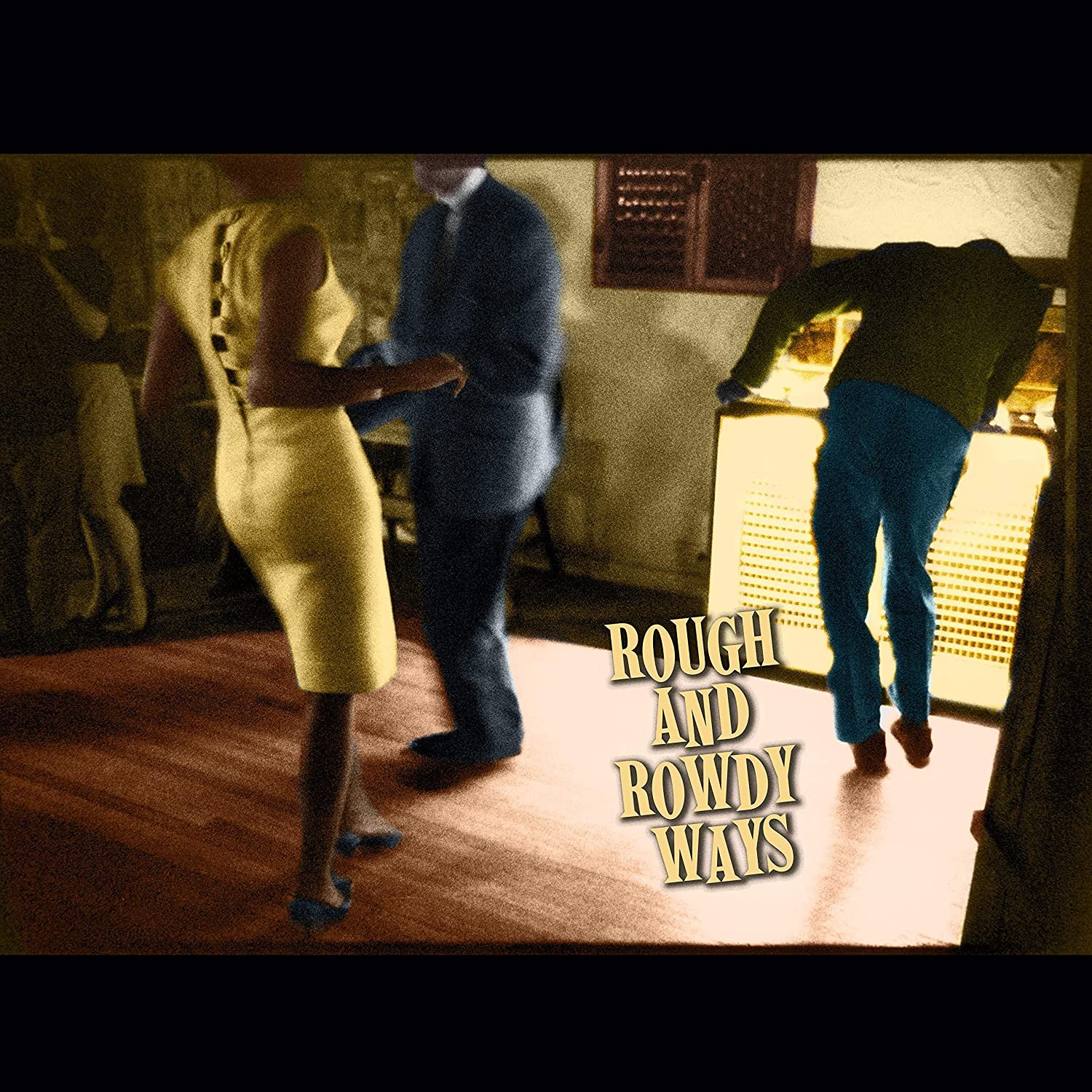

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about Bob Dylan:

Not all of the songs on Time Out of Mind are dark. The instrumentation for “Dirt Road Blues” is almost upbeat with a grooving guitar and buoyant organ riffs. The song sports the rock-a-billy influenced sound that Dylan would further explore on later albums. The song is mixed so that it almost sounds like you’re hearing it through tin-y stereo speakers, but the technique fits the overall feel of the song.

“Cold Irons Bound“ is unique to anything else in Dylan’s catalogue of work. It boasts the same bleak aesthetic that the album is built around, but it also shimmers with multiple layered guitars riffs, a propulsive bassline, and sprinkles of organ. The song often chugs with locomotive-like momentum, as Dylan’s vocals echo, ghost-like throughout the track, as he details his world falling apart around him, singing, “There’s too many people, too many to recall / I thought some of ’em were friends of mine / I was wrong about ’em all / Well, the road is rocky and the hillside’s mud / Up over my head nothing but clouds of blood / I found my world, found my world in you / But your love just hasn’t proved true.” The song earned Dylan a GRAMMY Award for Best Male Rock Vocal Performance, and it’s one that was well deserved.

Time Out of Mind does trip over itself a couple of times, first with the straightforward piano ballad “Make You Feel My Love.” Although penned by Dylan, it sounds out of place and like a peculiarity in Dylan’s catalogue. It’s almost redundant to say it would feel more at peace on an album by Elton John or Billy Joel, since a version of the song by the latter beat this one to market by about a month. “Make You Feel Me Love” just might be one of those songs written by Dylan that’s more successful when other people sing it, as Adele’s version graced her 2008 debut album 19 and became a mega-hit.

The album’s final song, “Highlands,” falters despite feeling very much like a Bob Dylan song. At sixteen and a half minutes in length, it’s the longest song that Dylan has ever released. Apparently inspired by both a late eighteenth century work by poet Robert Burns and an unknown Charley Patton song, Dylan sings 20 verses over a simple blues riff, without a chorus or bridge.

Dylan has an exceptional track record creating epic songs that are lyrically interesting and tell compelling narratives, such as “Desolation Row,” “Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts,” and “Hurricane.” “Highlands” seems directionless in comparison. What starts out as another meditation on loneliness devolves into close to self-parody, as Dylan spends seven verses and what feels likes half the song’s length sitting in a Boston diner, squabbling with a waitress about eggs and sketches. Furthermore, the unchanging riff drones on repeatedly. By minute four of the song, it’s clear that maybe a bridge or two would have helped.

Still, Time Out of Mind is today correctly remembered as an artistic triumph for Dylan, and the album was the initial piece of a later career renaissance that lasted for 15 years. In 2001, Dylan released Love and Theft, an album that was perhaps even better than Time Out of Mind. He continued this run with Modern Times (2006), Together Through Life (2009), and finally Tempest (2012). But by the time Tempest was released, Dylan’s voice sounded severely shot, possibly from a non-stop regimen of recording and touring. He eventually took a break to recharge.

Since 2015, Dylan has again returned to his folk roots, as the three albums he released prior to the original songs that comprise 2020’s Rough and Rowdy Ways all featured his versions of standards from the Great American Songbook. In 2016, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, and in true Dylan fashion, did not accept the award until mid-2017 at a private affair.

Regardless of what type of material he records, one thing that’s remained constant since the release of Time Out of Mind is that Dylan produced all of his subsequent material. Sometimes he’s listed under the alias of Jack Frost, sometimes he uses his own name. No matter how much success and acclaim this album earned him, he determined afterwards that he’d be the one primarily in control at the studio.

Time Out of Mind took risks, succeeded, and was rewarded. There wasn’t a Bob Dylan album like it before, and there likely won’t be another ever again. Even with its unorthodox production, it remained true to the type of music that Dylan had spent 35 years recording, while presenting his overall voice in a unique manner. The album still stands the test of time, and is rightly considered a seminal work of musical art.

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2017 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.