Happy 60th Anniversary to Bob Dylan’s second studio album The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, originally released May 27, 1963.

When The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan was released in 1963 it changed folk music and the country’s perception of young Robert Zimmerman, a.k.a. Bob Dylan, of Hibbing, Minnesota. When Dylan put out his eponymous first album the year before, he was seen as a gifted folk singer, but not necessarily a successful one. With the release of Freewheelin’ 60 years ago, Dylan was recognized as a serious singer-songwriter in the mold of Woody Guthrie, speaking profoundly about complex social and personal issues.

Freewheelin’ was Bob Dylan’s second album in a career that’s spanned six decades. His self-titled first album, while a creative success, did not result in a financial windfall for Columbia/CBS Records. John Hammond, who’d signed Dylan to the label, remained steadfast in his support and produced the sophomore album. His faith in Dylan’s ability was certainly well-placed, as the artist elevated his game during the year-long record process for Freewheelin’. Dylan’s songwriting, already unique among his contemporaries, markedly improved with this album and proved that he could be lyrically arresting no matter what the subject matter.

Freewheelin’ is the blueprint for a topically diverse album. Much of the album concerns the social unrest that was beginning to stir in the early to mid ’60s, particularly the growing Civil Rights Movement, as well as increasing anxieties about global conflict. And, like many great albums, the specter of lost love and heartbreak hangs over everything. Similar to his debut album, almost all of Freewheelin’ features just Bob Dylan, his acoustic guitar, and occasionally his harmonica, increasing its intimacy and personal touch.

The album begins with “Blowin’ in the Wind,” the definitive recorded protest song of the time period. Lots of people my age probably sang it around summer-camp campfires and/or in 7th grade music class. This hymn on integration and the failure to act is the prototype for the “folk songs that mattered.” Dylan’s decision to write the song’s verses as a series of unanswerable questions gives increased weight to the song’s scope. The verses themselves, like much of Dylan’s great early work, draw their power from their simplicity: “How many years can some people exist before they're allowed to be free? / And how many times can a man turn his head and pretend that he just doesn't see?”

The lesser-known “Oxford Town” further examines racial problems in the South, and while it never had the honor of appearing in Forrest Gump, it’s subtly poignant nonetheless. The song draws its inspiration from the tumult caused by James Meredith enrolling at the University of Mississippi, hence integrating the school for the first time. Because it was the early ’60s, his enrollment was met with serious resistance throughout the state, including from the governor at the time, Ross Barnett.

Dylan wrote the song in response to an invitation by Broadside magazine, a mimeographed and independent monthly folk magazine, which invited folk singers around the country to lend their creative voices to their reaction toward the incidents. Dylan continues to say more with less with verses like, “He went down to Oxford Town / Guns and clubs followed him down / All because his face was brown / Better get away from Oxford Town.”

Listen to the Album:

Global Thermonuclear War was a very real possibility when Freewheelin’ was released, as the U.S. was neck deep in the Cold War. Dylan manages to convey anger, sadness, and humor at the idea of the planet’s destruction on three separate songs. The first and perhaps the best known of the three is “Masters of War,” a scathing missive he unleashes on the military industrial complex. The song features Dylan at his most enraged, as he spits venom towards the hawkish, greedy, doddering politicians and businessmen.

The lyrics themselves seethe with contempt, as Dylan contends, “You fasten all the triggers for the others to fire / Then you set back and watch while the death count gets higher / You hide in your mansion while the young people’s blood / Flows out of their bodies and is buried in the mud.” Dylan’s fury towards these death merchants maintains at a constant roar throughout the song’s four and a half minutes, as Dylan decrees that “You ain’t worth the blood that runs in your veins” and “Even Jesus would never forgive what you do.”

“A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” is melancholy rather than angry. It’s frequently referenced that Dylan penned the song in response to the Cuban Missile Crisis, when in fact he had written and performed the song a month before the event occurred. The song features some of Dylan’s best and most complex songwriting not only to that point, but also across his entire career. He weaves surreal and striking images like something out of a Game of Thrones dream sequence, each symbolizing the sorrow and horror of war. Dylan famously said, “Every line in it is actually the start of a whole new song. But when I wrote it, I thought I wouldn’t have enough time alive to write all those songs, so I put all I could into this one."

With “Talking World War II Blues,” Dylan humorously improvises his view of what life would be like after the bomb drops. Dylan describes an increasingly absurdist view of life in New York City after nuclear destruction. Dylan “dreams” of wandering the mostly deserted streets, shunned or shot at by the few survivors he encounters, eventually seeking the solace of a recorded voice of an operator telling him the time as a substitute for human interaction. The dark wit belies the fear of loneliness and abandonment that would go along with being the sole survivor of a nuclear holocaust, while Dylan dispenses a little wisdom along the way. His most profound revelation? A Cadillac’s not a bad car to drive after a war.

Abandonment is a central theme throughout Freewheelin’, though often associated with heartbreak. “Girl From the North Country” features Dylan playing a simple guitar melody, singing about his lost true love from where “the rivers freeze and summer ends.” The song was influenced by Dylan’s first trip to England, specifically his immersion into the London folk music scene and his contact with many of its gifted singers. Dylan later re-recorded the song as a duet with Johnny Cash as the lead song for the country-tinged Nashville Skyline (1969). While it’s great to hear two masters collaborate and breathe new life into a great song, I’ve always preferred the original version.

Dylan also shares his thoughts on the disintegration of a relationship with “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right.” It features some of Dylan’s best and most intricate guitar playing on the album, as well as some of the best crafted lyrics. Apparently inspired by his breakup with Suze Rotolo, who had chosen to study abroad in Italy for an extended period of time, the song illustrates the little fictions we tell ourselves as a relationship ends in order to feel better about how things unfolded.

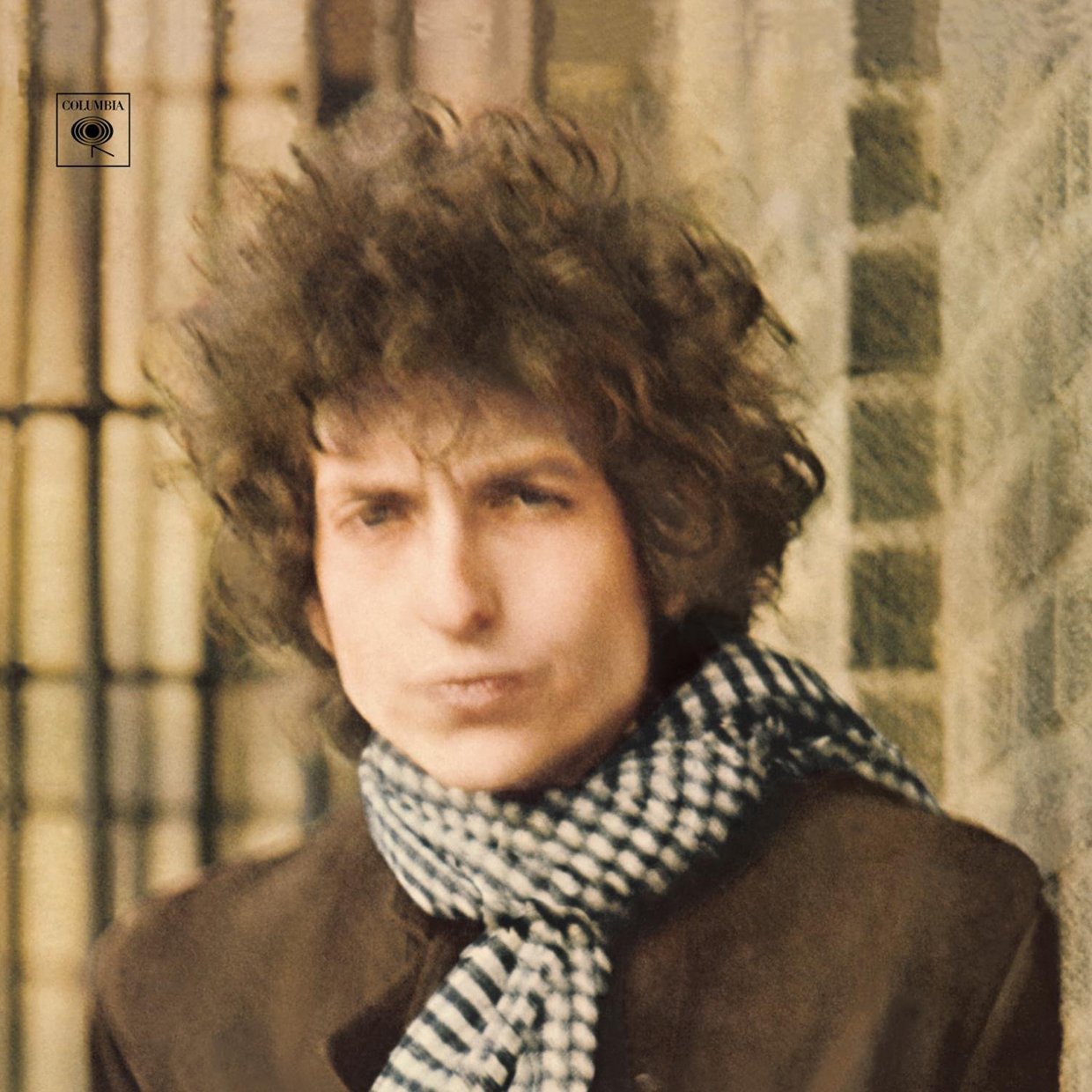

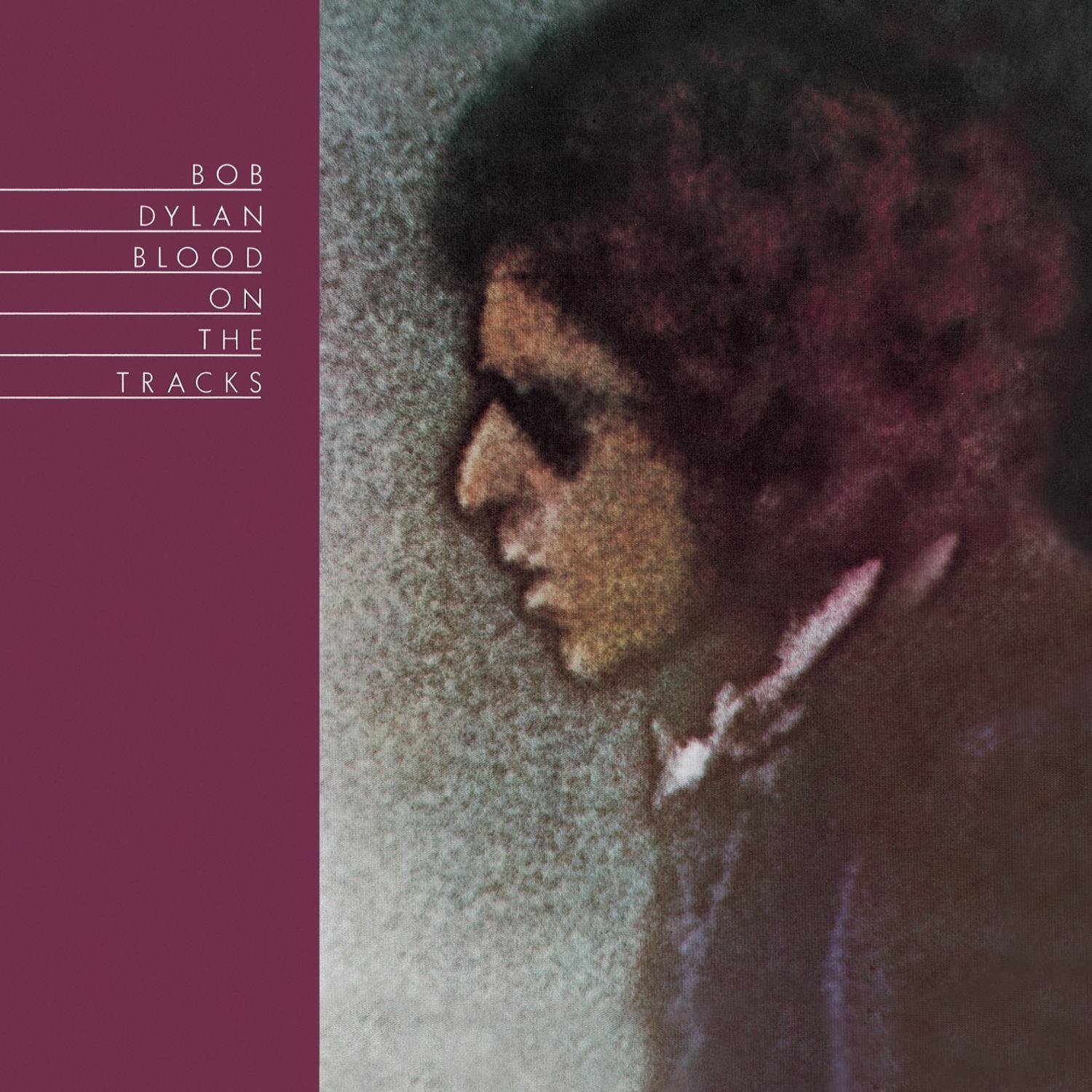

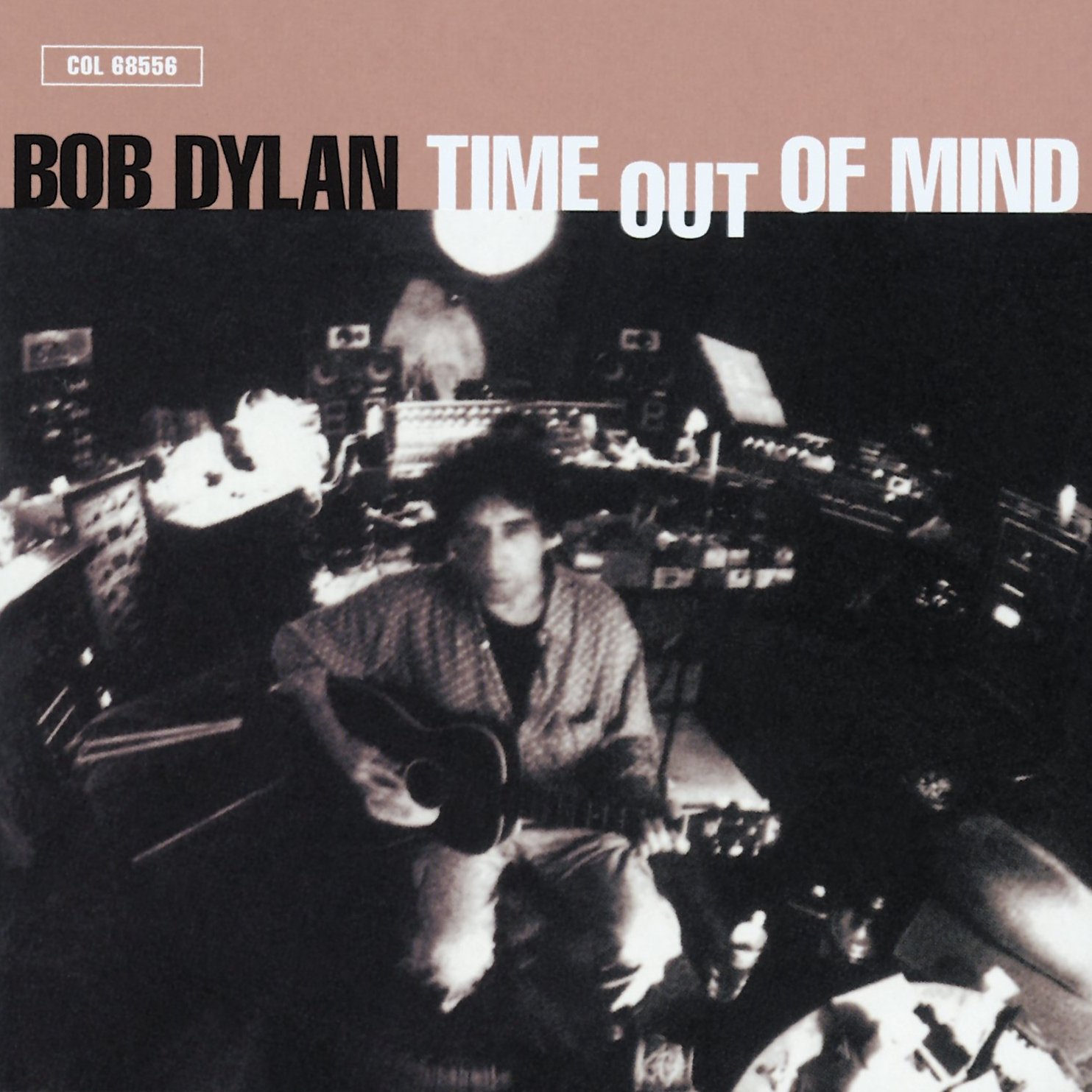

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about Bob Dylan:

Here Dylan attempts to convince himself that it was he that initiated their separation, even though his lyrics betray his true wishes throughout the song, with lines like, “But I wish there was something you would do or say / To try and make me change my mind and stay.” In the end, he ends things on a bitter note, trying to convince himself he was never happy, singing, “I ain’t sayin’ you treated me unkind / You coulda done better but I don’t mind / You just wasted my precious time.” Ouch, Bob. That’s kinda harsh.

Rotolo haunts other songs on the album, including the traditional blues number “Down the Highway,” where Dylan sings, “Yes, the ocean took my baby / My baby took my heart from me / She packed it all up in a suitcase / Lord, she took it away to Italy.” Dylan uses his skills of improvisation again on “Bob Dylan’s Blues,” a different sort of folksy blues number, where he relates mini-vignettes on the absurdity of life.

The majority of the songs on Freewheelin’ are Dylan originals. The notable exception is “Corrina Corrina,” a spin on the blues song “Corrine, Corrina,” which dates back 35 years before the album was released. Dylan gives a fresh spin to the song, altering the lyrics and infusing them with a sense of loss and lament. It’s the only song on the album where Dylan utilizes a few backing band members.

Freewheelin’ ends with “I Shall Be Free,” a goofy change of tone after what is nearly 45 minutes of thought-provoking material. Dylan reinterprets Lead Belly’s “We Shall Be Free,” which the Blues legend performed with folk music titan Guthrie, using the same melody and rhythmic cadence. It’s one of the more slight songs on the album, but there’s some biting subtext to go along with the light-heartedness. Alongside wig-wearing women slathered in “onion gook,” the great-granddaughter of Mr. Clean, and jokes about erections, he works in the references to Civil Rights, Jim Crow laws, and the inherent untrustworthiness of politicians.

The version of Freewheelin’ that most people know and love is technically not the original version of the album. Rare pressings of the album exist that feature four different songs that were removed from the album almost immediately after its initial release. The most notable of these is “Talkin’ John Birch Blues,” another talking blues song where Dylan mercilessly mocks the rabidly anti-communist John Birch Society. These four songs were removed at the behest of the parent record label CBS, much to Dylan’s chagrin, and replaced with four songs taken from later recording sessions, such as “Girl From the North Country” and “Takin World War III Blues.” As much as I enjoy “John Birch Blues,” I think the altered configuration flows better and is more consistent in tone. Besides, all four songs left off here have been made available on subsequent “bootleg” releases.

Six decades after Freewheelin’s release, Dylan’s personally affecting thoughts on race, war, and love remain as powerful as they ever were. Like a large chunk of Dylan’s catalogue, it’s required listening for anyone who really wants to understand popular music in the second half of the 20th century. And like a lot of great recorded music, it’s music that simultaneously feels of the time, yet still timeless and applicable to the world today.

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2018 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.