Happy 30th Anniversary to Tori Amos’ second studio album Under The Pink, originally released January 31, 1994.

In the fifth grade, my best friend Mary turned the entire class against me with razor-sharp precision. I can’t remember most of the details now, only that she told the entire class—including the boys—that she’d found a box of Kotex in my bathroom cabinet during a sleepover. It managed to provide the final “eww” factor in her calculated campaign, so that I ended up temporarily becoming the classroom pariah. (“That little bitch,” muttered my mother, the actual owner of the Kotex, shocking me as I sobbed against her.) Eventually, Mary and I made up, but it was more out of survival than a desire to ever be her friend again.

In 1993, Tori Amos was walking down the street with her friend Karen Binns, a drum-and-bass groove wafting out of a storefront as the two women were deep in conversation about the ways girls and women can be abusive to each other. It was a conversation they’d been having on and off for a couple years, and they’d even begun to develop their own language around it, referring to serial saboteurs as “Cornflake Girls.”

Something about the music in the background added to the conversation’s sense of importance. “I found it really difficult not to sway back and forth to this rhythm,” Amos recalls. “So as I was physically swaying, Karen asked me about the book under my arm. It was Possessing The Secret of Joy by Alice Walker. How women behave toward each other within the global culture of patriarchy is the discussion that the song ‘Cornflake Girl’ wanted to take part in.”

It was, in fact, the discussion Amos’ entire 1994 album Under The Pink wanted to take part in. A barbed silver thread of women-to-women difficulty is woven through songs like “Bells For Her,” “The Waitress,” and “Cornflake Girl,” while Amos admonishes the patriarchy directly on the song “God.” An album full of dissonance and experimentation, Under The Pink presents an intricate collage of womanhood under the patriarchy using personal narrative, found letters and objects, human-rights violations, political intrigue, well-known historical figures, and—as is very characteristic of Amos—well-timed cheekiness and humor.

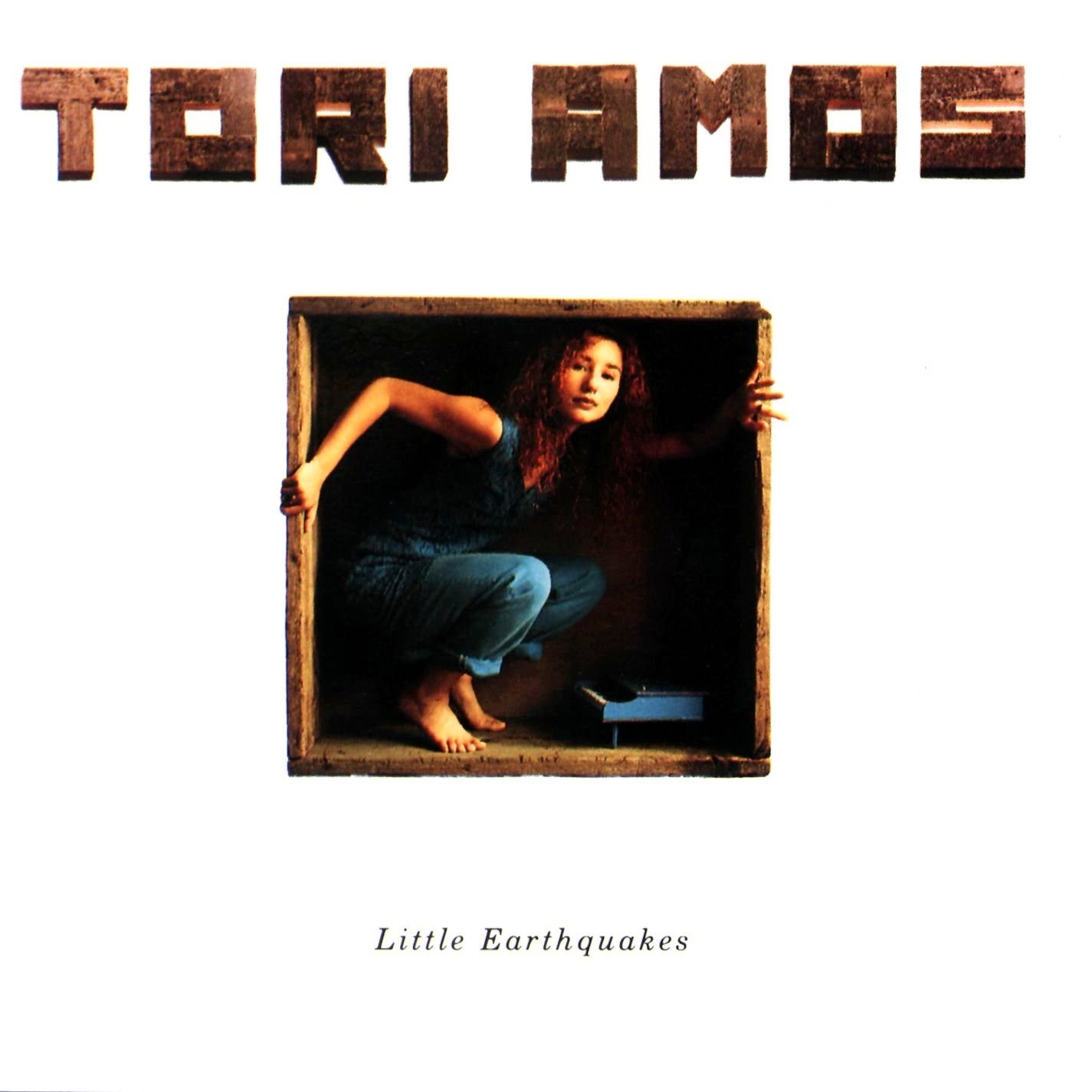

After her success with her debut Little Earthquakes (1992), Amos was looking for a fresh perspective. “I felt like I dealt with the son on the first record, so I was going after the father,” she told Canada’s MusiquePlus in 1994. “Violence between women—that just happened to dump in my lap. I think, in a way, I put some clothes on after Earthquakes. That was so stripped and raw that I just felt like I couldn’t expose myself in that way.”

The album was originally to be called God With A Capital G, but Amos went with Under The Pink to connote a more universal stripped-ness. “Under the Pink, the way I see it, is if you ripped all our skin off, we’re all pink, and that is what goes on under that,” she told deejay Bob Waugh during an interview on WHFS.fm. However, pink, too, is the color most often associated with the feminine and so Under The Pink is Amos focusing particularly on the inner and intra workings of women.

Yellowjackets, the Showtime series that compellingly combines Alive with ’90s teen girl coming-of-age, managed to present all of Under The Pink’s concepts somewhat literally in its second season last spring. A girls’ soccer team survives a plane crash in 1996, only for the teens to begin to starve once winter hits the Canadian wild in which they’re stranded. Their descent into cannibalism is set against an icy backdrop of bitter infighting, betrayal, and backbiting for the affections of the lone teenage boy. At the same time, the survivors’ deep love for one another and interdependence into adulthood are also poignantly depicted in the show.

Nora Felder, Yellowjackets’ music supervisor, didn’t intend to use multiple songs from Under The Pink, but she chose two needle drops—“Bells For Her” and “Cornflake Girl”—simply because they fit so well with the show’s theme of feminine ferality. In the “Cornflake Girl” scene, a starving girl decides to take a nibble out of her dead best friend’s detached, frozen ear. “I remember the editor called me saying, ‘I’m presuming you want this to hit on the bite,'” Felder said of the line “This is not really happening” arriving at just that perfect moment.

Watch the Official Videos:

Under The Pink has a distinctly wintery feel, and photographer Cindy Palmano and Karen Binns, Amos’ stylist, captured that sensibility in the album art. “I remember Cindy, Karen, and I having long, long talks about how to represent emotional danger,” Amos recalls. “Cindy came up with a glass world with a lone woman [Tori] having to navigate it with bare feet. Karen came up with the idea of white. I dug it because if the lone woman missteps, then there is nowhere to hide all that blood on such a pretty white dress.”

Despite its icy aesthetic, Under The Pink was recorded in the middle of the desert. To remove herself from all outside influences, Amos decided to build a studio in a 150-year-old hacienda in Taos, New Mexico. Amos and her boyfriend and collaborator Eric Rosse nicknamed the studio the “fish house” after their recording equipment had, unfortunately, been shipped alongside crates of seafood.

They used their unusual, remote surroundings as inspiration for unorthodox approaches and experimentation. Rosse completely dismantled and reassembled an upright piano to get the old-timey bell-like tones on “Bells For Her,” detuning it, smashing the soundboard, and muting some of the strings. Meanwhile, they fiddled around with industrial loops mixed with acoustic piano on other tracks. During other points in the recording process, they rolled large ball bearings on the strings of Amos’ Bösendorfer as well as metal food cans on the other instruments for subtler effects.

Despite its experimentation, Under The Pink’s opening track “Pretty Good Year,” is a traditional ballad with misty wistfulness—and an added surprise of eight bars of grunge. It’s one of the few songs on the album featuring the male perspective, inspired by a letter Amos received from a despondent fan who felt he couldn’t understand women. “Greg is 23, lives in the north of England, and his life is over in his mind,” Amos told the Baltimore Sun. “In that early-20s age, with so many of the guys—more than the girls [who are] a bit more, "Ah, things are just beginning to happen—for the guys, it was finished. The best parts of their life were done. The tragedy of that for me, just seeing that over and over again, got to me so much that I wrote ‘Pretty Good Year.’”

The next song “God” is full of grinding industrial loops, distorted guitars, and screeching dissonance, the perfect complement to Amos’ displeasure. “God sometimes you just don’t come through / Do you need a woman to look after you,” she sings, pairing ethereal vocals with scolding confrontation. “When I sing this song, it’s been freeing for me to go, ‘Hey buddy, you need to sit down, put your feet up, have a cup of tea, and maybe you need a little advice,” Amos told VH1. “And I think that’s a beautiful thing. It’s calling forth the goddess energy, the female side.”

Under The Pink’s wintery feel is conveyed viscerally on “Bells For Her” where Rosse’s deconstructed piano creates an eerie, bell-choir effect through moody fog and misty window. When Amos wrote the song, the words poured out of her so that she had to listen back to the recording to know what she’d been saying. She immediately understood that it was about a conflict with her best friend Nancy Shanks, a.k.a. “Beanie.”

“‘Bells For Her’ is about a woman, a best friend, and how we just couldn’t communicate,” Amos recalled to MusiquePlus. “She made choices that made her have to…she chose to be with a man who was treating her like dog shit.” It created a seemingly insurmountable rift in her friendship with Beanie. “I couldn’t stay there and lie about it when I saw him destroy her,” Amos said. “The good news is she finally got out of it. Not until this year, though. When ‘Bells For Her’ was written, I didn’t know if we’d ever speak again.”

While penning “Past The Mission,” Amos knew that she wanted Nine Inch Nails’ Trent Reznor to sing with her on it. So she traveled to Los Angeles where Reznor was recording The Downward Spiral in the Sharon Tate house. Nearly as odd as its recording environment, “Past The Mission” begins with a Bavarian oom-pah rhythm, and then dissolves into a warm, fuzzy-at-the-edges duet that meanders baroquely down twisting paths and strange little byways.

The next song, “Baker Baker,” rises and falls with a sad, reflective vulnerability. It was Amos’ attempt to contend with some of the armor she’d built up after documenting her brutal rape on Little Earthquakes. “After I wrote ‘Me And A Gun,’ I had to work through trying to open up intimately again with a man,” Amos told Katie Couric on NBC Today. “And it’s been a bit of a… I’ve been working on it with my boyfriend.”

The melancholy of “Baker Baker” is offset by the exuberant, galloping cabaret of “The Wrong Band,” which Amos wrote about a sex worker she befriended while performing in piano bars in Washington, D.C. “She finally had to leave because she felt her life was in danger because she was seeing somebody on the Hill, and she knew too much,” Amos recalls.

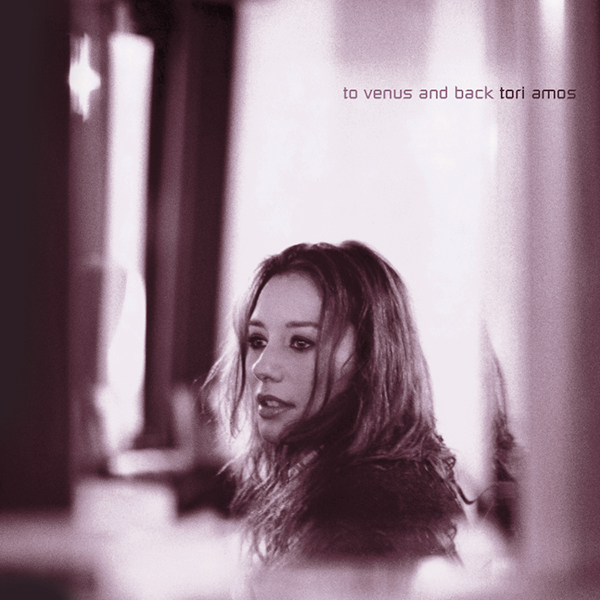

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about Tori Amos:

In another well-timed exit, Mary—remember her, the girl who turned the entire fifth-grade class against me?—ended up moving away not long after the Kotex incident. (Now as an adult, I understand that Mary was conflicted about her budding womanhood—who could blame her—and foisted that on me.) But I still think of her whenever I hear Under The Pink. Most of my childhood was spent on an American army base in Cold War Germany and, as was customary in the military, families were always coming and going. So if you had a problem with someone, you really didn’t have to wait long before they transferred elsewhere.

Then, some years later when I was 16, life had gotten stale until a new boy swaggered onto the school bus one day in baggy skater pants and Adidas. It was instant attraction—lots of smiles and little stolen glances—and it wasn’t long until he and I were sitting next to each other every day to and from school. The only problem was he still had a girlfriend on another army base, and so I told him I wouldn’t date him until he’d broken it off. Still, we continued to hang out constantly and, somewhat inevitably, ended up kissing before I left on a trip over Spring Break.

So you can imagine my horror on the first day back from vacation when I found him sheepishly sitting with a totally different girl on the bus. Turns out, he’d begun dating her just as I’d first laid my towel down in the hot sand in Ibiza. Now, there’s absolutely no doubt that I’d been shady making out with him, but this chick was getting twice-reheated leftovers—and she even had the audacity to act smug about it.

I can’t say exactly what it was, but I hated this girl with a blind rage. I was much angrier at her than at him; probably because she and I had mutual friends, and because it was my first taste of this type of betrayal. Coincidentally, Under The Pink had come out only a couple months prior to the awful incident, and it became my constant companion. Every time I heard “The Waitress,” that girl’s self-satisfied face would float in my mind, particularly whenever Tori began to shriek “I believe in peace, bitch.”

“Tell me about the waitress you want to kill,” Bob Waugh asked Amos on his WHFS.fm radio show in 1994. “Well, I’m a waitress, too, so we’re on equal footing. So for all those waitresses out there, it’s about two waitresses who hate each other,” she explained. “And I happen to hate this girl with a passion, and have no problems wanting to just throw her up against the wall and rip her head off. It’s kind of shocking.”

Amid clanking, metallic loops and understated piano, “The Waitress” presents the deceptively simple story of two waitresses working alongside each other in a spirit of competition. “I don’t go into the details of why. Why isn’t the issue,” Amos told the Baltimore Sun. “The issue is that I thought I was a peacemaker, and this violence has totally taken control of every belief system that I have.” Let’s be clear: I didn’t actually want to kill the girl on the bus—and I’d argue Tori doesn’t actually want to kill the waitress. But it took some serious soul searching for me to forgive her. It wasn’t until the guy proved himself to be a player and a cheater in other scenarios that I realized she and I had both been victims of his bullshit. As women, we simply expect more from each other than we do from men.

Jangly and bluesy and now instantly recognizable, “Cornflake Girl” delineates two types of girls —Cornflake Girls and Raisin Girls—and we’re to understand that being the former just isn’t the way. Although I always imagine the movie Heathers when I hear this song, its inspiration was much more serious. You’ll remember that Amos had a book under her arm—Alice Walker’s Possessing The Secret of Joy—on the day that groove wafting out of a storefront inspired the song.

“[That book] opened up the conversation to a practice with which I had been unfamiliar. It is now widely known as FGM, or female genital mutilation,” Amos writes in Resistance. “This is child abuse on a grand scale.” The female circumcision—which often removes the clitoris, making pleasure impossible for the remainder of life—is typically performed by women on girls. Amos’ horror is reflected in the line “This is not really happening / You bet your life it is.”

Pensive and cascading, the next song “Icicle” morphs female pain into pleasure with an ode to masturbation. The song depicts a gathering of churchgoers in holy communion while the protagonist joyfully explores her own body—“Getting off, getting off, while they’re all downstairs.” Keeping with the theme of communion, it’s followed by “Cloud On My Tongue,” one of the album’s more cryptic songs. "It’s dealing with Eve—dealing with feeling inferior, that somebody else has something that you want,” Amos explains.

Funky and psychedelic, “Space Dog” is my favorite track on Under The Pink, containing a line that always makes me chuckle: “Is she still pissing in the river now / Heard she’d gone, moved into a trailer park.” Like Amos with Beanie, my best friend Nikki once had to give me a dose of tough love—I was a budding teenage alcoholic—and, in a fit of frustration, she shouted, “You’re going to end up living in a trailer park!” It was no doubt inspired by this song (we both loved Tori). And it made me pull my shit together.

Under The Pink’s final song, “Yes, Anastasia,” sprung from a bout of food poisoning Amos suffered after eating crabs in Maryland. Apparently, Amos was so weak and delirious that she ended up hallucinating the czarina Anastasia Romanov. “Her being visited me and said, ‘You need to tell my story.’ And I'm like, ‘Oh, come on. I'm losing crab at both ends,’” Amos recalled to the Baltimore Sun. Joking aside, Amos saw parallels between the kidnapping and rape she experienced in “Me And A Gun” and the horrors Anastasia endured at the hands of the Bolsheviks. Amos challenged herself when writing the nine-minute song, using Debussy as inspiration in the first half and the Russian composers in the second half.

Ultimately, after seemingly insurmountable woman-to-woman difficulty—“Girls, girls, what have we done / What have we done to ourselves”—the song touchingly concludes Under The Pink with a woman from far back in history lending Amos her strength. “The line ‘We'll see how brave you are’ walks with me every day,” Amos said in the album’s deluxe liner notes. “The idea of bravery has to be to keep asking yourself, "What kind of energy do I want to put out into the world today, and what do I want to take in?"

Listen: