Happy 25th Anniversary to Tori Amos’ fourth studio album From The Choirgirl Hotel, originally released May 5, 1998.

In my memory, I pick up Kara at the Frankfurt airport and we drive directly to the concert venue. But I know that’s got to be wrong, because Kara’s just gotten off an eight-hour transatlantic flight and she’s exhausted. I can see it in the smeared mascara under her eyes, and in the way she’s slumped in the plastic chair at the baggage claim. She stands up, all 6 feet of her, and I realize that college-age Kara has changed from the scrawny seventh grader she was when I last saw her. “Kara, you have huge boobs,” I say, and we giggle, and the ice has been broken.

I’ve been listening to From The Choirgirl Hotel since it came out that past Spring, lying on my bed in the dorm with my headphones on, soaking in its dark whirlpool of “Liquid Diamonds,” “Raspberry Swirl,” and the looping, industrial wasteland of “Iieeee.” My roommate is on a semester abroad, and I gloriously have the room to myself. Choirgirl has become an interior, private affair—if someone were to walk in, it would feel like I’d been caught scratching my butt, or talking to myself. So when Kara emailed to tell me Tori Amos would be playing in Frankfurt that summer on her Plugged Tour and that the show would coincide with her, Kara’s, visit, I was conflicted. I wanted to see Tori, but seeing Tori with someone I hadn’t hung out with in years seemed…awkward. I’m precious about only a handful of artists, but Tori Amos is one of them. What if Kara were to do something annoying, like sing along loudly to every song? I buy the tickets anyway.

That summer of 1998, I’m prickly and raw. Before Kara left our army base in Germany at the end of middle school, we’d thrown a going-away party for her at my house. Like practically everyone in that era, we had a bulky Panasonic video camera that, red light conspicuously blinking, made its rounds through the party. My dad cheerfully grills hotdogs, my mom happily refills cups of lemonade, and my brother unleashes his rip-roaring laugh as he runs between two girls doing lazy cartwheels on our lawn.

But what a difference six years can make. Now, in ’98, my parents are divorced, my brother’s been to rehab, and my mom is married to a dude she knew for two weeks before deciding to run off to Denmark (the Vegas of Europe for quickie marriages) to get hitched. I feel a burning shame when I see my new “family” through Kara’s eyes. Kara who, back in Virginia, still has a dad who grills hotdogs and a mom who smiles as she refills your cup of punch, and a brother whose only fault is that he’s a little bit of a dork.

Choirgirl salves this pain. “We don't often see our own stories,” Amos wrote in her 2005 memoir Piece By Piece. “Good artists are the ones that whisper our own stories back to us.” That’s what Amos has always been to me—someone who finds the perfect tone and exactly the right words when I’m in the thick of it and can’t see shit through the bug-smeared windshield. The songs morph over the years, too. What might have spoken to me about my severed family in 1998 might later resonate on a completely different subject—an unforgettable night out, a job that’s driving me crazy, my divorce, a move across the country, an illness, unexpected good news, getting older.

From The Choirgirl Hotel was recorded during a raw time in Amos’ mid-thirties when she suffered a series of miscarriages while aching to become a mother. “I had a hard time getting from the bed just to the kitchen,” she told MTV News in 1998. “You’re so helpless when you’re having a miscarriage because there’s nothing you can do to save this little life. You can’t be the woman you were before you carried this life, and you’re not a mom, so you’re in this no-man’s land.” At one point on the journey, she dealt with a male doctor who was controlling—menacing, even—in his attempts to decide what was best for her and her body, and the experience left her shaken. “After the second miscarriage, I made From The Choirgirl Hotel,” she writes. “I took on the subject of my loss directly in those songs. The album clearly came from a place of grief, but also from deciding that instead of fighting the patriarchy and expressing rage and defiance, I had to do something new.”

Watch the Official Videos:

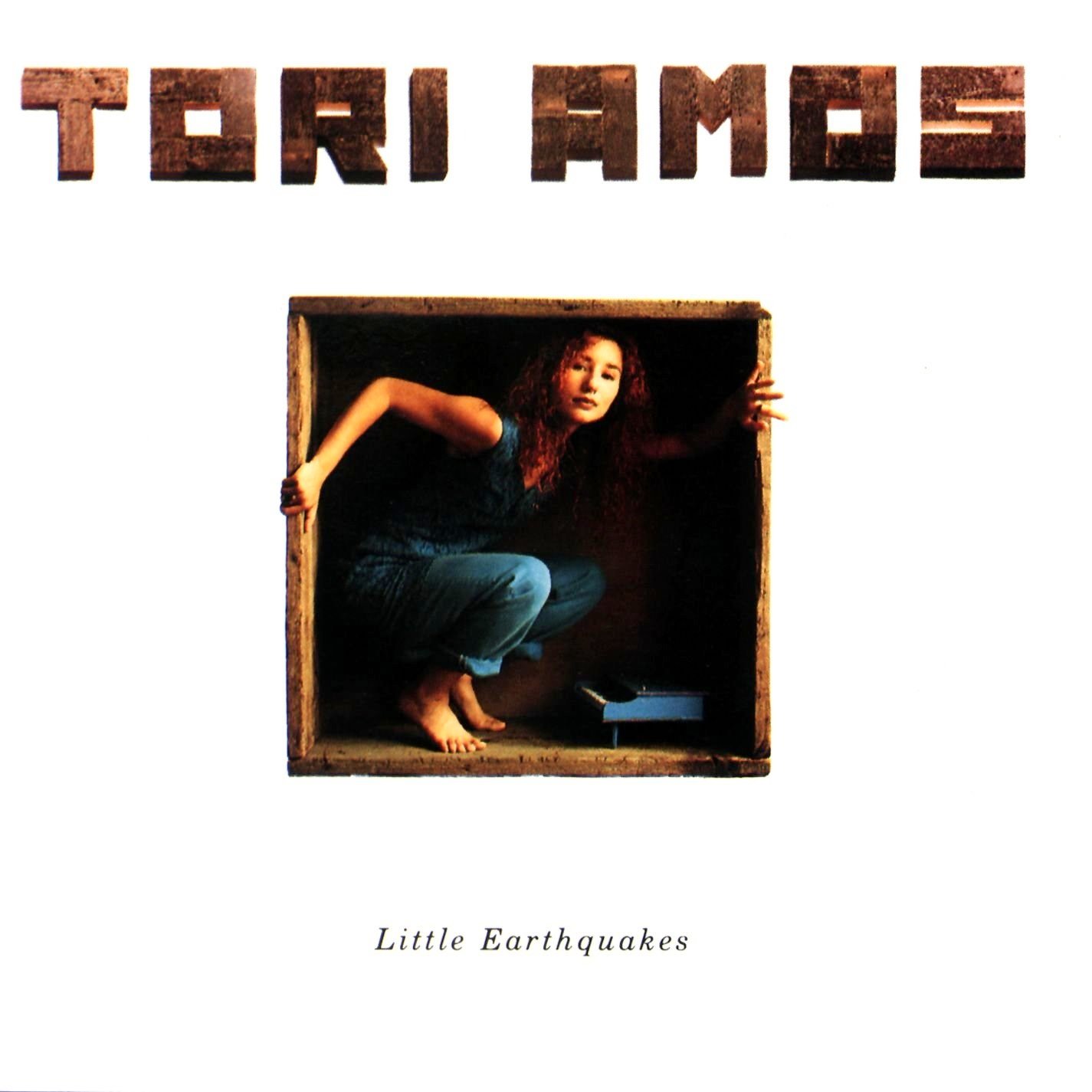

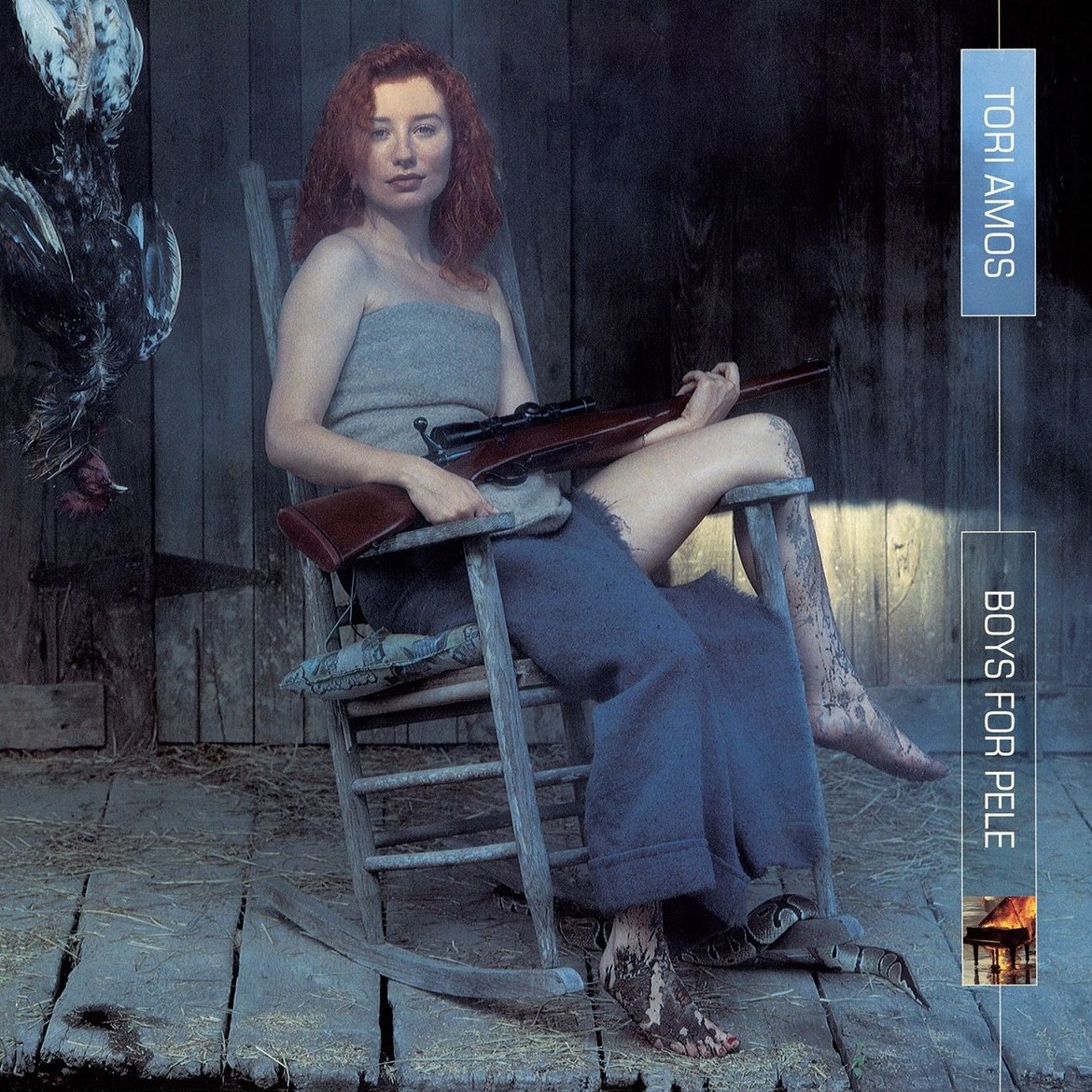

The album sees Amos abandoning the baroque, harpsichord-punk influences of her previous album Boys For Pele (1996)—as well as the signature singer-songwriter ‘Tori-ness’ of Little Earthquakes (1992) and Under The Pink (1994)—in favor of drum programming, keyboards, string sections, and thick electric guitar. “[Choirgirl Hotel] was a very different type of record for me, and that came from listening to OK Computer,” she told Pitchfork. I didn’t know half the time what Thom [Yorke] was talking about, but it didn’t matter. Maybe it was way over my head—a lot of things are—but I felt it.”

Choirgirl Hotel is dark and heavy, weaving an avant-garde atmosphere with trip-hop and techno influences, and it fuses sonic landscapes and instrumentation that shouldn’t work well together, but absolutely do. Because it takes such a wide turn from Amos’ well-established formula, Choirgirl often seems to the be the “forgotten” or overlooked album, but it’s one of my all-time favorites. Despite Amos’ palpable sadness on Choirgirl, it teems with an unapologetic sensuality that screams of a woman coming into her own. Amos is no longer a twenties girl-woman, but a grown-ass woman. Hearing it at 20, it gave me something to aspire to.

Amos, who’s part Cherokee, has often talked about how, in the writing process, her songs come to her as separate entities belonging entirely to themselves—she often refers to them as “girls” —and not from her as their creator. “The romantic myth of the artist says that you are the Source. I have no illusion about that,” she says. “I think this goes back to my grandfather. That was his great gift to me—Native Americans don't believe they are the Source. They have access to the Source.”

However, Amos experienced the songs a bit differently on Choirgirl. “These songs were the supportive, nurturing women,” she explains. “This was an unbelievable mothering I was getting.” As for the “hotel” part, it was as if all of these women (as opposed to girls) were coming together as a force under one sturdy roof. “I saw some of them in Room 13, I saw some of them answering the phone, and it became very much like a traveling group of wanton women,” she says. So, while grappling with the unfulfilled mother inside of her, Amos was simultaneously being unshakably mothered via the music she was accessing. During the dissolution of my family in my teens, I had often taken on the role of a mother to my brother, and a mother to my mother, which left me aching for some mothering myself. No doubt that’s why Choirgirl Hotel is the album I reach for whenever I, too, need some of that nurturing, big-mama energy.

“Spark,” the first of Choirgirl’s wanton women, is moody and cold-metallic, and it alternates between traditional ballad and slow underwater interludes. “She’s addicted to nicotine patches / She’s addicted to nicotine patches,” Amos sings, nearly listless. “She’s afraid of a light in the dark / 6:58 are you sure where my spark is.” I had given up a pack-a-day Gauloises habit in ’98, and so I could easily relate to the bored, distanced itchiness of the song.

The next track, “Cruel,” stretches out the nicotine-fiending sulk, serving up an eddying groove of marimbas while Amos rocks on with her blasé detachment— “No cigarettes, only peeled Havanas for you / I can be cruel / I don’t know why.”

“Black Dove (January)” is a more traditional, soaring piano ballad in the vein of Amos’ widely beloved “Winter.” It manages to capture coldness and warmth at once, and Amos opened with this song at the show Kara and I attended at Frankfurt’s Alte Oper (old opera house) that June of 1998. It was my first time seeing Amos perform, and I was absolutely blown away—as I totally expected to be. (Also, Kara ended up being a perfectly suitable concert buddy—no loud singing along!). The venue was somewhat small and intimate, so we were able to crowd in right in front of the stage. There are more up-tempo songs on Choirgirl than on any of Amos’ other albums, so it was an incredibly lively, dynamic, even dance-y sort of show. Kara and I left the Alte Oper basking in catharsis and cloud-nine bliss, reliving the highlights frequently throughout the rest of her stay in Germany.

“Raspberry Swirl” is the album’s total banger: robotic, pounding, and whirling with a provocative sexuality that demands female fulfillment—“If you want inside her, well / Boy, you better make her raspberry swirl.” I had so much fun at the show in Frankfurt that I ended up seeing Amos perform again at my university in the fall. Naturally, she performed “Raspberry Swirl” at both shows, with everyone—even the tamest concertgoers—jumping out of their chairs and dancing like maniacs. “[Amos] embraces her piano with a passion that’s almost overwhelming, at times pounding the keys with such intensity that it’s difficult to believe that stunning melodies still emerge,” observed the local Morning Call.

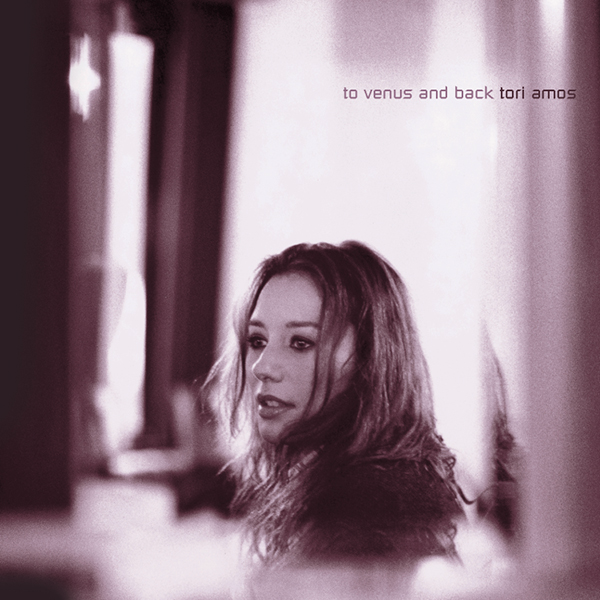

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about Tori Amos:

A sweeping ballad, “Jackie’s Strength” combines an Amos family memory of the JFK assassination with Tori’s own misty nostalgia for her teen years. “I was three months old to the day when my mother, after hearing over the radio that JFK had been shot, put me down and said a prayer—and prayed for Jackie’s strength,” Amos recounts. Written not long before Amos married sound engineer Mark Hawley, the song reflects on birth, death, and marriage, as well as girlhood merging with womanhood. With its emphasis on ’70s nostalgia (themed lunchboxes, pot smoking, David Cassidy), the ballad, though quite different sonically, draws an obvious comparison to Smashing Pumpkins’ “1979” of a few years earlier.

“Iieee,” one of my favorite songs, pairs a slow, circular groove with Amos’ expansive moans and melancholy, and it paints a dark, murky watercolor of the no-man’s land Amos spoke of when discussing her miscarriage. “‘Iieee’ has a Native American influence in it, when you hear the rhythm,” she says. “And yet there’s a little bit of that New Mexican driving in an old dilapidated Mustang and you’re just on your own and you drive for days and days and days, and you think you’re at the end of the earth and it’s just you.”

My other favorite, “Liquid Diamonds,” features a swirling, engulfing ocean of bass, drums, and piano. It’s sleek and seductive, submerging the listener fully in a black, glittering, silken dream that beckons you to stay under just a little bit longer. In contrast, the strutting “She’s Your Cocaine” captures an essence of freewheeling ’70s rock while Amos conjures her beloved Robert Plant in the wails.

Chorgirl’s vibe does a complete 180 with “Northern Lad,” a cashmere-blanket of a ballad about a long-lost love. “‘Northern Lad’ is probably the love song on the record—you’ve got to have one of those on every record,” Amos says, adding with a sly smile, “Yeah, I know a northern lad.” The album’s underwater-electric sexiness resumes with “Hotel,” where we’re invited to imagine a less sweet and much more sultry type of affair—“Met him in a hotel / You were wild / Where are you now?”

The perfect mother doesn’t exist, and Amos explores this idea on the bluesy, pedal-steel “Playboy Mommy,” about an old-fashioned sort of floozy (“a good friend of American soldiers”) who apologizes to her dead child for not measuring up. “I never was the fantasy of what you wanted / Wanted me to be,” Amos sings like slow-dripping honey, and it’s a tearjerker of a song that both mothers and daughters can relate to. To close the album, “Pandora’s Aquarium,” with its evening piano-bar sensibility (like one might find in a hotel), resolves Choirgirl’s themes with equal parts aqueous sadness and steely resolve.

Amos would end up sorting out the medical issues underlying her miscarriages, finally giving birth to her daughter Natashya in the year 2000. “Are you surprised that you were able to make music, create anything, out of something that was as gutting and exhausting as a miscarriage?” MTV veejay John Norris asked Amos in 1998.

Amos is silent for a moment, then answers, “The songs started to take me by the hand and said, ‘You can’t create as a mother at this time, but we’re coming to you. Can you hear us? Honor that this is another form of the life force.’ This album is about having an appreciation for the life force in a way that I hadn’t really seen before.”

Listen: