Happy 25th Anniversary to Saint Etienne’s fourth studio album Good Humor, originally released May 4, 1998.

“The sounds of the city are the sounds that bring to us news of love and adventure. And this is the sound of Saint Etienne—a sound that is both utterly metropolitan and effortlessly clean. It is the sound of love without blame, and hope without conditions.” – Douglas Coupland, March 1998

Indeed, just as the Canadian novelist Coupland writes in Good Humor’s liner notes, Saint Etienne’s music embodies the dynamism and romance of the urban experience, primarily as it pertains to London, but also universally applied for those of us who call cities home. Inherent within many of the trio’s songs is an understated yet profound empathy for the often troubled and lovelorn city-dwelling souls that inhabit the narratives they spin.

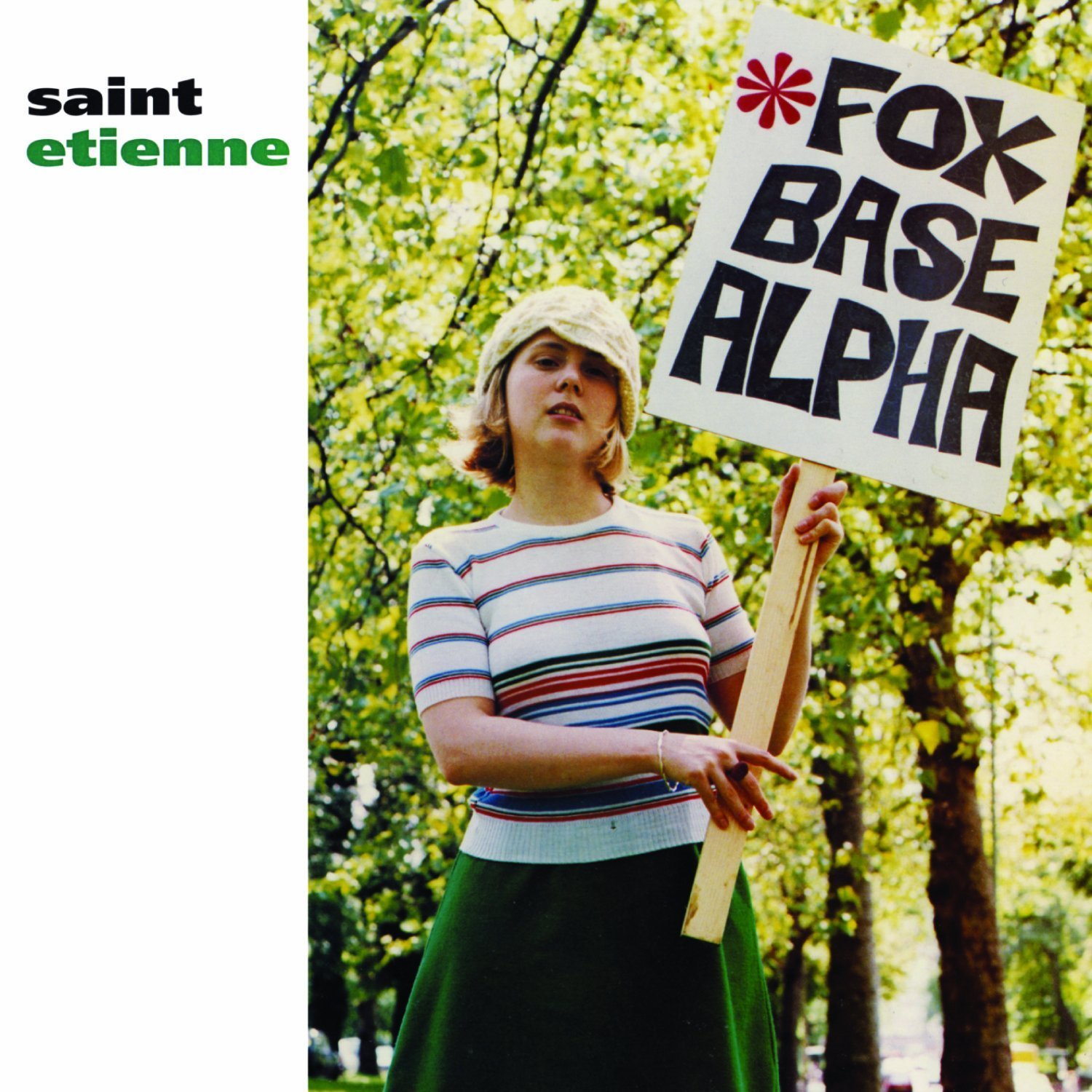

Wholly devoid of pretension and never pandering to the listener, Saint Etienne’s approach to crafting pop music has always been informed by their affinity for artistic adventure, purity of intent and passion for the genre’s rich, kaleidoscopic history. This has been true since their earliest days, with their formal arrival back in 1991 by way of their feted debut album Foxbase Alpha and on through to its acclaimed successors So Tough (1993) and Tiger Bay (1994).

By the latter half of the 1990s, three albums into their then-ascendant recording career, kindred musical spirits Sarah Cracknell, Bob Stanley and Pete Wiggs had solidified their proven reputation for crafting sophisticated, dancefloor-friendly pop that circumvented the genre’s more saccharine and superficial strains. But just as Saint Etienne were seemingly hitting their creative stride following a whirlwind four-year, three-album run, they defied the conventional, “more where that came from” route by taking an extended—albeit, well-deserved—hiatus from recording.

During the three years that elapsed between Tiger Bay’s release and their return to the studio, the group remained quite active, however, as they delivered the hits-to-date collection Too Young To Die: Singles 1990-1995 (1995), the excellent remix compilation Casino Classics (1996) and the rarities assemblage Continental (1997) in steady succession. Together, all three of these releases kept the band visible among their growing legion of devotees, while also establishing their dedication to inviting listeners into the deeper corners and contours of their expansive recorded oeuvre.

Cracknell also recorded and released her inaugural solo album Lipslide (1997) during this sabbatical, which her bandmate Wiggs wryly referenced during a 1998 interview when asked about Good Humor’s delay. “Sarah did a solo album, which took a bit longer than planned,” he said. To which she half-jokingly replied, “Sorry. That’s not very nice.”

Meanwhile, and for better or worse, the Britpop phenomenon had proliferated during this period, within the broader context of the so-called “Cool Britannia” cultural paradigm that pervaded music, fashion, sports, and yes, even politics, with the election of Labour Party leader Tony Blair to the prime minister post in the spring of 1997.

When the trio reconvened that same season to commence recording sessions for their fourth album, they did so in mutual repudiation of the overarching forces at play and in stark opposition to what they perceived to be the stagnation of pop music. “I wasn’t listening to Britpop, which was still around but in its terminal phase, and most dance music had gone trancey and flaccid,” Stanley confides in the liner notes for Good Humor’s 2010 deluxe edition.

They also rebelled against being pigeonholed by others within the rigid classification of “Britishness,” redirecting their creative energy toward American shores. “We were fed up with the ‘quintessentially English’ tag, so there was a bit of a backlash about that,” Cracknell explains in the deluxe edition’s liner notes. “And there was a very British/Britpop thing going on and it was also an answer to that. We were trying to think of the America that we grew up hearing about. I don’t think any of us had spent much time in the States, but it’s what we’d heard about or films or TV we’d seen.”

Listen to the Album:

In light of their subsequent output and particularly their two most recent albums Home Counties (2017) and I’ve Been Trying To Tell You (2021), which both pay reverential—and unequivocally beautiful—homage to their native UK, Good Humor’s stateside focus stands as an anomaly within the expanse of their discography, but it was the thematic pivot that they needed at the time. It also coincided with—and perhaps catalyzed—their desire to embrace a handful of creative and professional transitions that informed Good Humor’s genesis.

In addition to being their first—albeit only—album recorded for Creation Records (home to such British rock heavyweights as My Bloody Valentine, Oasis, and Primal Scream) after multiple Heavenly Records commissioned, self-produced releases, Good Humor represented the first time that the group relinquished the production reins to an outside collaborator. Hoping to be guided toward new, more experimental approaches to advancing and diversifying their sound, the group hired Swedish producer Tore Johansson, who was just about a year removed from orchestrating The Cardigans’ breakthrough third studio album First Band on the Moon (1996).

“We wanted to try something different to make our job more interesting and fun and it was a challenge,” Cracknell shares in the deluxe edition’s liner notes. “We’d got quite used to sampling things and using technology, so it was exciting to go and use real musicians and there were so many in Sweden.” Stanley shares the same sentiment, explaining, “We wanted to make it ‘organic.’ Not that we were going for a trad-rock authenticity kick, just that being non-musicians it seemed like an intriguing challenge to make an album from scratch, no samples, nothing digital.”

Recorded at a brisk pace in the spring of 1997 at Johansson’s Tambourine Studios in Malmö, Sweden, Good Humor was originally slated for release that summer. But due to Creation’s resources being committed to their all-hands-on-deck promotional push behind Oasis’ quagmire of a third album Be Here Now, Good Humor’s arrival in the UK was delayed until May of the following year, with a subsequent stateside release managed by the famed Seattle-based Sub Pop label a few months later in September 1998.

The finished product found the group seamlessly embracing their nuanced sonic direction, replete with meticulously arranged, shapeshifting soundscapes that provide somewhat incongruous—yet wholly intriguing—backdrops for their cleverly constructed portraits of dysfunctional characters. In fact, it is precisely the dark-and-light contrasts that exist within the album’s thematic, lyrical and melodic dimensions that make Good Humor such an absorbing listen overall.

A wise choice for the album’s official first single, the piano-driven, drama-filled “Sylvie” is a propulsive shuffler with house-like flourishes that belies the bitter undertones in the song’s lyrics. Inspired by—and originally intended for—the prolific French-language singer Sylvie Vartan, the song examines a case of sibling rivalry (and jealousy) that pervades matters of the heart, with Cracknell adopting the guise of the older sister admonishing her younger sibling (“Sylvie, girl, I'm a very patient person / But I'll have to shut you down if you don't give up your flirting”).

In a similar buoyant sonic vein, the kinetic “Lose That Girl” is a standout that the band had originally recommended as the second official single (they were overruled by the label, it would seem, as “The Bad Photographer” was slotted in instead). Throughout the track, Cracknell inhabits the voice of a clairvoyant confidante who regrets not being more forthright in warning her friend about his incompatible girlfriend, with the latter’s most regrettable crime being her questionable taste in music (“On her radio she'd turn the disco down / Disco down”).

Owing to its lite and breezy composition with flute and harpsichord prominently featured, you’d be forgiven for overlooking the subtle yet sinister hit-n-run climax of “Goodnight Jack,” which depicts a scorned lover exacting revenge upon her object of affection by running him over outside of his office with her Ford Capri. Brutal.

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about Saint Etienne:

The aforementioned second single “The Bad Photographer” coasts along with a jaunty swing that obscures the more malevolent tale at hand. With the devil to be found in the details as the song unfolds, it’s a tale of a West London photo shoot gone awry, as the ill-intentioned photographer manipulates his subject and presumably sells compromising photos of her to a tabloid.

Loosely informed by Glen Campbell’s classic 1967 breakup song “By the Time I Get to Phoenix,” the protagonist in the uptempo, brass-infused stomper “Split Screen” is flipped to the female lover’s perspective. With allusions to the cinematic trick of split-screen imagery, the song conveys the divergent course the relationship in question has taken for both parties. It also functions as an ode to liberation, with Cracknell defiantly declaring in the chorus, “Now I really don't care / Cause I'm dying to get the sun in my hair / Yeah I really don't care / That I'm here and you're still there / Yeah I really don't care / Cause I'm going to breathe the country air / Yeah I really don't care.”

References to America emerge most notably in two of Good Humor’s eleven tracks. The gentle, percussive sway of album-opener “Woodcabin” betrays the drearier, more noirish strains of the American narrative the song conjures, as the velvet-voiced Cracknell sings, “A redwood tree / The radio / They moved them down the hall / A beauty queen from Idaho / Was broken in the fall,” later reflecting, “In twenty years this place will be / Just like L.A. today.” Later, toward the album’s conclusion, “Erica America” presents the portrait of a girl who wishes to flee from her smalltown confines with grand visions of escaping to America, including a well-positioned reference to the band America’s chart-topping early ‘70s single “A Horse with No Name.”

Evoking the old adage that suggests that “distance makes the heart grow fonder” with a title inspired by the name of a Japanese café the band once visited while on tour, the wistful “Mr. Donut” finds the contemplative Cracknell celebrating the connection to her partner back home (“When I'm far from home / You call me on the phone / Tell me everything that's happening in England.”). Similarly endearing, the effervescent love song “Been So Long” calls to mind When Harry Met Sally, in its rendering of friends becoming lovers, forever altering their relationship dynamic.

Not only my favorite offering in their sterling discography to date but also one of my favorite albums of all time, Good Humor remains an integral and inspired part of Saint Etienne’s still-evolving story. Thirty-plus years into their recording career, and the trio’s fidelity to the genre is stronger than ever, as evinced by their majestic most recent album I’ve Been Trying to Tell You and, invariably, by whatever new musical paths they will traverse together in the years to come.

Listen: