Happy 30th Anniversary to Paris’ second studio album Sleeping with the Enemy, originally released November 24, 1992.

As an Amazon affiliate partner, Albumism earns commissions from qualifying purchases.

It’s safe to say that 1988 to 1992 was the golden era of political and socially conscious hip-hop. Spawned from over a decade of Reaganomics, the Crack Era, the proliferation of street gangs, and about a hundred other factors that I don’t have space to write about here, this style of hip-hop was characterized by rappers who were fired up and couldn’t take it anymore. Met with apathy and outright hostility from the United States’ ruling class, these emcees and crews used their talents to vent their anger and frustration towards the systematic oppression of the Black race.

Thirty years ago, Oscar “Paris” Jackson, Jr. released Sleeping with the Enemy, one of the last great political albums of the time. Unfortunately, he was knee-capped before the album was even completed, a victim to spineless record executives afraid to see their names in the paper. Which is really faulty, because Paris’ sophomore release had so much to offer, and could have been an even bigger political statement.

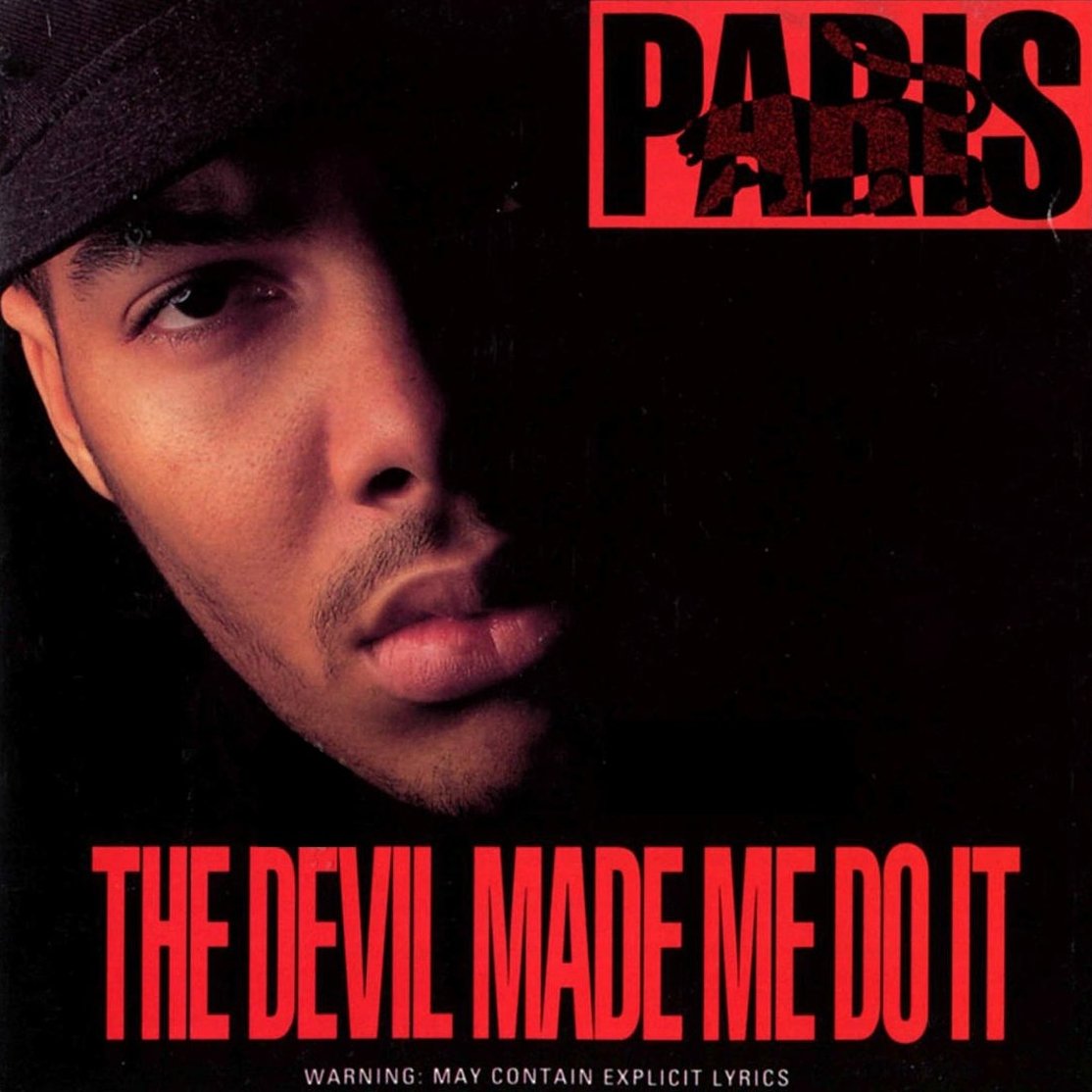

Paris had bum-rushed his way onto the scene in 1990 as the “Black Panther of Hip-Hop.” Armed with tracks like “Break the Grip of Shame” and “The Devil Made Me Do It,” the Bay Area-based emcee delivered uncompromising hip-hop with a political bent, influenced by artists like Public Enemy, Boogie Down Productions, and Rakim. He signed with Tommy Boy Records and released his debut album The Devil Made Me Do It (1990), a raw and fierce call for revolution against a crooked government system.

He eventually began recording a follow-up to The Devil Made Me Do It, but was soon met with resistance from Tommy Boy’s parent label, Warner Bros., who began objecting to everything from the album’s lyrical content to its album cover. This situation was more common than it should have been for hip-hop artists trying to release an album. It was, after all, an election year.

Sleeping with the Enemy was one of the main victims of the post “Cop Killer” reality. After the song by Ice-T’s heavy metal group Body Count became a cultural flashpoint and fodder for right-wing politicians, many other rappers were subjected to often ridiculous amounts of scrutiny. Record labels, particularly Warner Bros., were trying to avoid their label’s hip-hop releases becoming talking points for ambitious politicians seeking low-hanging fruit. Hence labels shelved or severely delayed a few projects that had the whiff of controversy. And, well, Sleeping with the Enemy gave off more than a whiff.

The most prominent arguments seemed to center around the content that involved President George H.W. Bush. Paris made no secret of his disdain for the 41st president, from his domestic policies to the Gulf War that he championed in the early 1990s. The album’s proposed cover featured Paris hiding behind a tree near Washington DC’s Capitol Building, gun in hand, lying in wait for an unsuspecting Bush. Paris also assassinates Bush on two different occasions on the album, first during a commando-style raid that opens the album, and second with a sniper attack that appears on the intro to the song “Bush Killa.”

Warner Bros. also shied away from a song that focused on delivering violent consequences towards the reprehensible police officers terrorizing local citizenry. Then Vice President Dan Quayle had singled out 2Pac’s “Souljah Story” and its supposed ties to the shooting death of a police officer, calling for his debut LP 2Pacalypse Now (1991) to be pulled from shelves. So the label proceeded with an excessive amount of caution.

The label ultimately shelved the album, with Paris eventually negotiating to get released from his contract and take the master tapes with him. Through complicated maneuvers, Paris was able to put out Sleeping with the Enemy independently through his own Scarface Records, which may have had its beginnings as Rick Rubin’s Sex Records vanity label. But all of the delays had ensured that the project wouldn’t hit the shelves until after the 1992 presidential election.

Paris has bristled at the idea that the legacy of Sleeping with the Enemy has been reduced to just the controversy. While he grants that these angry sentiments are an important component of the album, he’s asserted that they shouldn’t define it. “It was supposed to be an album that was presented as representing the totality of the experience of Black people in America at the time,” he told the Library Rap podcast.

Sleeping with the Enemy is a solid follow-up to The Devil Made Me Do It, even if it isn’t as strong overall. Paris writes in the liner notes that “this album was censored and rushed,” and both seem to ring true. Things seem stretched out as the album progresses, with a few too many unnecessary skits and a remix that doesn’t add too much to the original song. However, Paris definitely has a lot on his mind, covering a wide array of topics and areas of Black life in the United States.

Sleeping with the Enemy features some of the earliest production credits and appearances by DJ Shadow. According to Paris, he met Shadow while he attended UC Davis. Shadow, a Davis local and a teenager at the time, would occasionally be in the studio for Paris’ radio show through the university’s on-campus station. Paris would occasionally play Shadow’s mixes live on the air, giving the aspiring beat-maker and DJ some of his first exposure.

Shadow is credited with “Samples” for three of the tracks on Sleeping with the Enemy. It’s not quite clear what that credit entails. For his part, Paris told Library Rap that’s Shadow’s contributions entailed giving him the Blackbyrds’ album that featured the sample for the project’s first single, “The Days of Old,” as well as doing the scratches on a pair of songs.

Shadow makes an early appearance on the album, providing cuts for Paris’ opening sonic salvo, “Make Way for a Panther.” The song plays like an updated version of Public Enemy’s “Lost at Birth,” the cacophonous opening track to their Apocalypse ’91 (1991) album. Paris has said that the legendary group shaped his musical direction throughout his career, and “Make Way…” definitely feels like an homage.

Similar to the Public Enemy recording, the song begins with an extended instrumental intro, accompanied by Shadow’s furious scratches. Paris then firmly sinks his teeth in the jugular of those who actively work to suppress Black history and perpetuate myths that people of European descent created civilization. “Take and rape, shape your brain and claim that what's ours is theirs, so you fear the white race,” he raps. “And hate and never think about the fact we built it all / Got you thinking all the black can do is crawl.”

Throughout the early portion of the album, through songs like the title track and “House N****s Bleed Too,” Paris takes aim at members of the Black community who aid and abet white supremacy. “Every brother ain’t a brother” becomes a common refrain, particularly as he directs his ire towards Black members of the media who chose to parrot talking points that denigrate the African American population. “Bush Killa” is a well-executed, two-part “expression of aggression” by Paris. In the face of a society indifferent and often outright hostile to the suffering of the Black population within the United States, he expresses that militant action is the only true solution. “So don't be telling me to get the nonviolent spirit,” he snarls. ”’Cause when I'm violent is the only time the devils hear it.”

“Coffee, Donuts & Death,” which Warner Bros. balked at releasing, is a menacing and evocative entry. Paris delivers a lengthy verse over a haunting piano, describing the methodical stalking and killing of the police officer responsible for the 1989 repeated rape of an Oakland woman. “This pig finna kiss the lead man,” he growls. “I’d rather just lay you down, spray you down,” he growls. “’Til justice come around / ’Cause without it there’ll be no peace / The only motherfucking pig that I eat is police.”

“Guerillas in the Mist” went through a few iterations before Sleeping with the Enemy was released. At some point, it was conceived as a team-up between himself and radical left-wing hardcore band Consolidated. This version had a distinctly more rock bent and a verse from Adam Sherburne, the group’s lead singer; it appeared on Consolidated’ s Play More Music, released about two months earlier. For Sleeping with the Enemy, Paris cuts Sherburne’s verse and repositions the song as a sequel to “Break the Grip of Shame,” right down to the use of the same beat. Paris has said that lyrically, the song conveys a level of rage and anxiety in a way that he envisioned.

Paris takes things to the streets with “Conspiracy of Silence,” a rousing track about revolutionary action, featuring guest appearances by homie K.P. and a young Son Doobie from the group Funkdoobiest. Back in 1992, Son Doobie was just about the last rapper I expected to appear on a Paris album, as his earlier appearances featured him as an extemporaneous, off-the-cuff rapper. Here he impressively matches Paris’ revolutionary fervor, while maintaining his off-kilter mic presence. “And I'm certain you'll get played like Richard Burton,” he raps. “Barrels to the kneecaps, you best believe that.”

Paris is correct in claiming that much of the variety heard throughout Sleeping with the Enemy was ignored due to the more provocative subject matter. Indeed, some of Sleeping with the Enemy’s best moments are its quieter ones. Or certainly the ones with a less chaotic production style and blunt subject matter.

“The Days of Old,” the album’s first single, centers on Paris reminiscing on the days of his youth, when he states people were more respectful of each other and less easily spurred towards violence. The choice to sample the aforementioned Blackbyrds’ “Mysterious Vibes” is an inspired one, as the smooth shimmering sample connotes a more contemplative time. “Thinka ’Bout It” is an underappreciated entry on Sleeping with the Enemy, as Paris warns the Black population against various means of self-destruction, from criminal activity to not practicing safe sex. The song is one of the better tracks to utilize the sample from the Gap Band’s “Outstanding,” with the meditative piano complementing chirping synths. “Funky Lil’ Party” is an exceptional low-key entry, as Paris chronicles a night out with his crew, hitting up a hype night spot that eventually gets broken up after a gun fight.

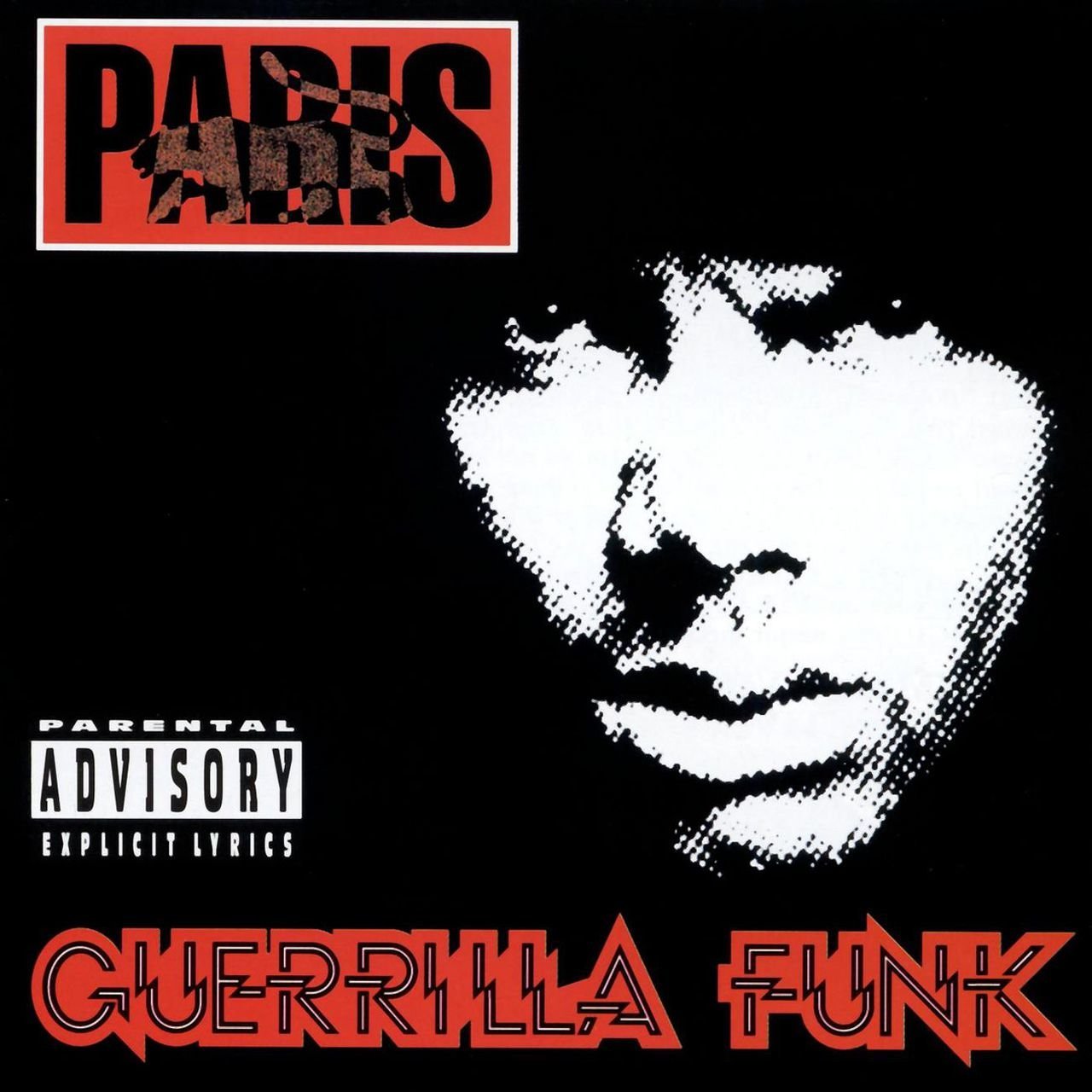

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about Paris:

“Assata’s Song” shows another facet of Paris’ personality, as he uses the song to honor Black women. Paris told the Rap Library podcast that he wrote the song after journeying to Cuba and meeting Assata Shakur and Fidel Castro. Paris examines a real and well-rounded look at Black femininity, rather than attempting to fetishize it. He always turns a critical eye inwards, admonishing himself for the lack of care he’d shown in his past. “But then I seen that the game was ignorant,” he raps. “The time had come for me to break away from that / Don’t you know there ain’t no future in hurting our own / It's bad enough that the trust and love are gone.” The accompanying track is smooth, making use of a live saxophone and mellow piano groves.

Paris was certainly put into a difficult situation when it came to releasing this album. However, the music reveals that it deserved to be judged on its own merits, rather than through the prism of those openly hostile to hip-hop culture. Incendiary political hip-hop is a lot harder to come by these days, as most major record labels flee from any sort of confrontation. Regardless, Paris gave it a fitting 21,000-gun salute with Sleeping with the Enemy, and its lessons are still applicable today.

As an Amazon affiliate partner, Albumism earns commissions from qualifying purchases.

LISTEN: