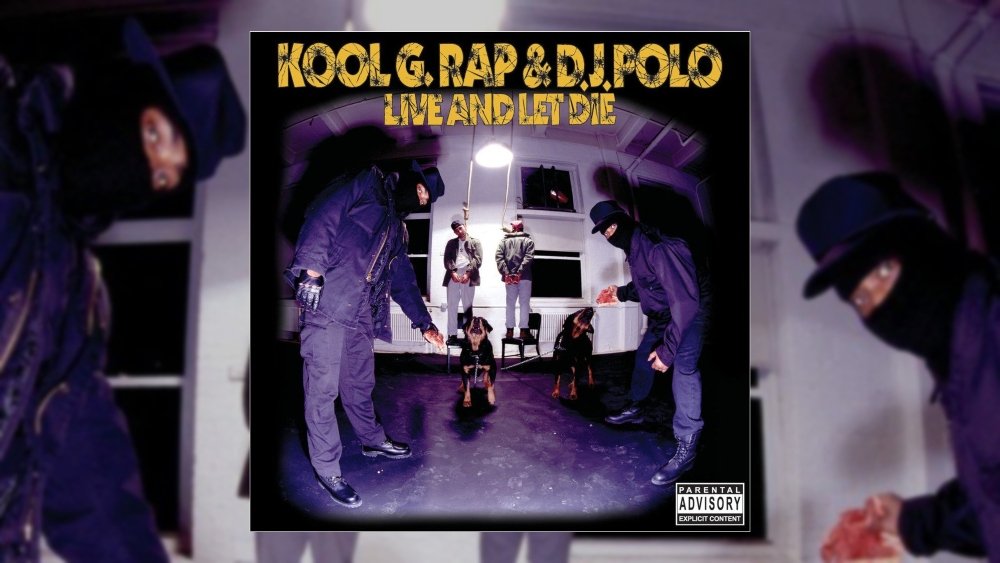

Happy 30th Anniversary to Kool G Rap & DJ Polo’s third and final studio album Live and Let Die, originally released November 24, 1992.

[Editor’s Note: Live and Let Die is not currently available in authorized form via major streaming platforms, hence the absence of embedded audio from the full album below.]

As an Amazon affiliate partner, Albumism earns commissions from qualifying purchases.

Few albums released in 1992 were as grim as Kool G Rap & DJ Polo’s Live and Let Die. Nathaniel “Kool G Rap” Wilson and Thomas “DJ Polo” Pough had established themselves by creating music that painted unflinching portraits of life in the inner city. Their third album, released 30 years ago, is the most lyrically masterful album of nihilistic sentiment ever recorded. It was Ready to Die before Ready to Die, but bereft of any attempts at radio appeal.

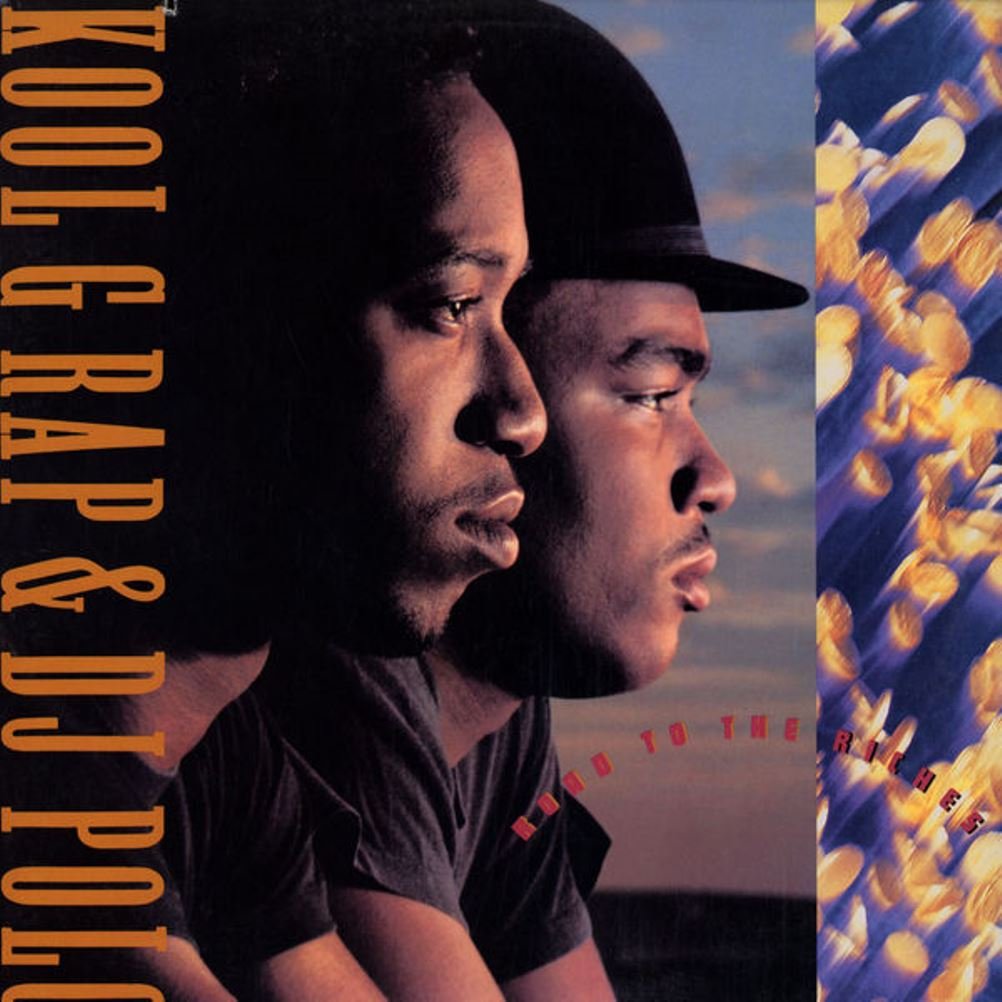

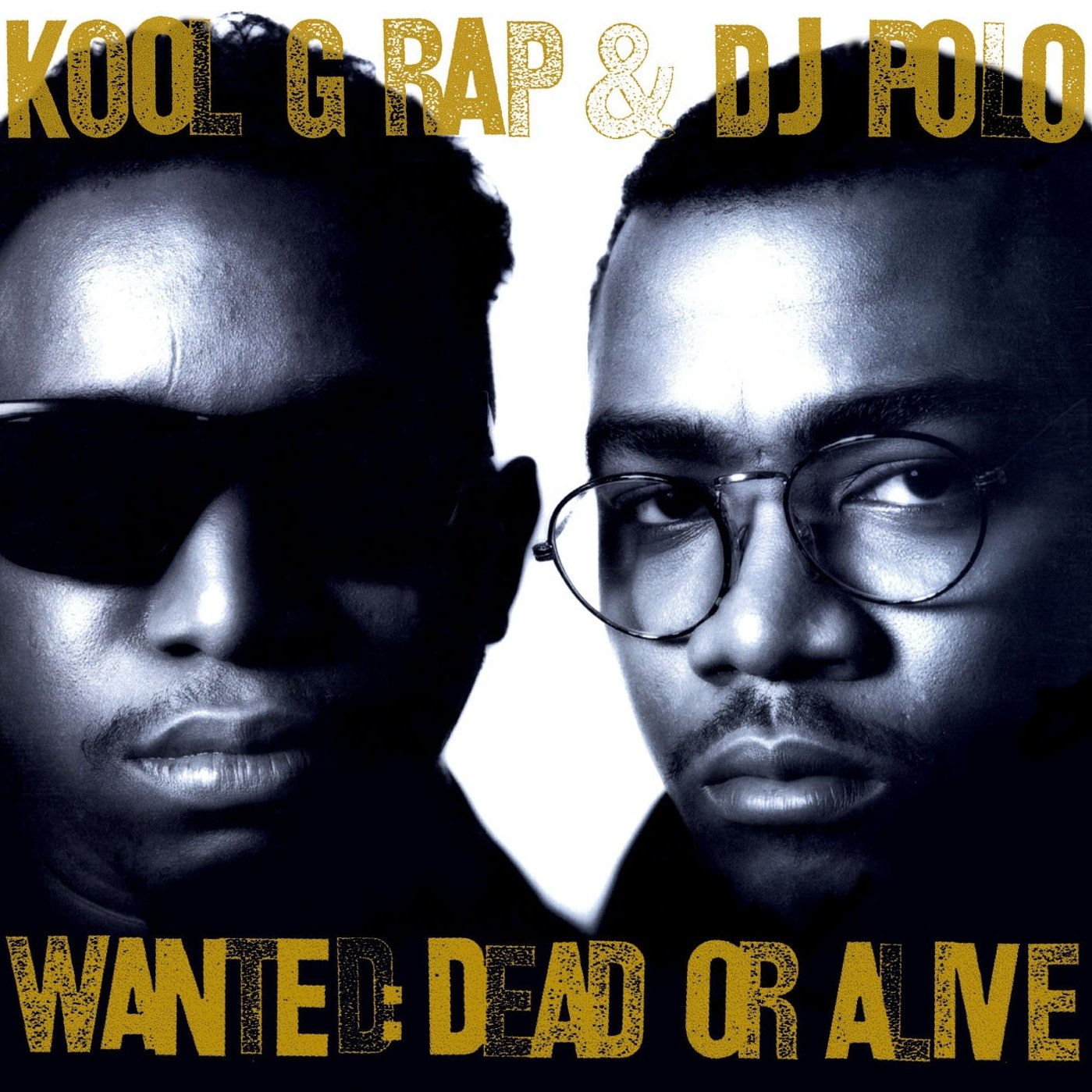

It’s not an exaggeration to say that Kool G Rap & DJ Polo were legendary by the time Live and Let Die dropped. Kool G Rap had already earned a place as one of the best lyricists in hip-hop music through the duo’s first two albums, Road to the Riches (1989) and Wanted: Dead or Alive (1990). He became known for his razor sharp lyricism, uncanny storytelling ability, and his distinctive voice, including his thick lisp. Tracks like “Road to the Riches,” “Men at Work,” “Poison,” and “Streets of New York” are among the best hip-hop tracks ever released. His verse on Marley Marl’s “The Symphony” posse cut is one of the best rap verses ever recorded. Rap royalty like Nas, Big Pun, and The Notorious B.I.G. have all counted him among their top influences.

Kool G Rap is a pioneer of “Mafioso rap,” or, essentially rap music conveyed from the perspective of The Godfather or Goodfellas-styled gangsters. It’s understandable for emcees who choose to rap about carrying out illegal activities in their songs to leverage the more “glamorous” examples already available in popular culture. But even as Live and Let Die features a good deal of Mafioso rap tracks, it’s also deeply influenced by the straight-up gangsta rap from places like California and Texas that were earning national attention at the time.

Part of this influence is evident in the sound of the album’s production. For Live and Let Die, Kool G Rap sought different producers than he had usually relied upon. Marley Marl had handled the entirety of the production on Road to the Riches, and he had worked with Large Professor, Eric B., and Biz Markie on Wanted: Dead or Alive. For Live and Let Die, he went a decidedly different route, enlisting Los Angeles beat maker Sir Jinx to set the album’s musical tone.

Before collaborating with G Rap, Sir Jinx was known for his work with Ice Cube and his affiliates. Jinx had come up with Cube, releasing music together as members of the group C.I.A. in the mid-’80s. He became known as an important contributor to the production of Cube’s solo projects, especially his early efforts like his 1990 debut AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted, the Kill At Will EP (1991), and Death Certificate. He also produced the major of WC and the M.A.A.D. Circle’s 1991 debut LP Ain’t a Damn Thang Changed album as well as tracks for Yo-Yo.

Sir Jinx utilizes a production style that carries the same vibe as his work with the Bomb Squad on AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted. The sound is incredibly dense, creating an often-crowded wall of sound. The soundscape fits in well with the album’s subject matter. G Rap had become known for creating intricately constructed battle rhymes and vivid stories of crime and urban decay. Some songs are cinematic, others are introspective, and a few are almost cartoonish in their levels of violence. But overall, like Kool G Rap & DJ Polo’s previous albums, Live and Let Die is a largely unrelenting account of crime and criminal behavior, punctuated by a few displays of humor and lyrical wizardry on G Rap’s part.

It was the album’s crime-based subject matter that led to its delays and almost prevented it from being released at all. Live and Let Die was originally supposed to be released in late 1991, but was nearly derailed by two separate incidents. Things were first thrown out of whack by the notorious Gilbert O’Sullivan sample case, which was lodged against fellow Juice Crew member Biz Markie and Cold Chillin’ Records, the results of which forever changed the nature of sampling on hip-hop records. Hence, it took nearly a year to complete the required sample clearance.

Watch the Official Videos (Playlist):

The “Cop Killer” controversy, stemming from the infamous song recorded by the Ice-T fronted heavy metal act Body Count, proved to be even more damaging. It was the start of an election year, and candidates were looking for easy targets to score points. Although “Cop Killer” was not a hip-hop record, hip-hop artists were the ones who felt the brunt of its fall-out, as protests against rappers for their potentially controversial lyrical content became national news. As a result, albums by Time Warner-affiliated artists fell under the microscope.

Eventually Time Warner opted not to distribute Live and Let Die due to issues with its cover artwork (featuring two federal drug agents strung up and seconds away from being set upon by a pair of hungry Rottweilers) and the content, which was deemed to be too violent and graphic. Truthfully, the content of Live and Let Die is no more extreme than the content of most other “gangsta rap” records of the era, but Time Warner was loathe to have its releases become political talking points.

One thing that’s missing from Live and Let Die is DJ Polo. It’s never been clear how much Polo contributed to the group: while he has some production credits on their first and second albums, it’s been disputed whether or not he provided any of the scratches on any of their albums. On Live and Let Die he seems to be extraneous. He provided some adlibs at the beginning of few songs, but G Rap barely mentions him at all throughout the project. So it came as no great surprise when the two parted ways after this album.

G Rap uses his nearly unparalleled ability to create cinematic narratives throughout Live and Let Die. He leads off the album with “On the Run,” in which he tells the tale from the perspective of a low-level gangster who decides to steal a whole shipment of money and cocaine from a prominent crime family. On “Great Train Robbery,” he and four accomplices try to pull off a low-level version of The Taking of Pelham 123, and attempt to strong-arm passengers of a subway train at gunpoint.

One of the album’s strongest tracks is also its first single, “Ill Street Blues,” another cinematic track where G Rap describes his various illicit escapades, engaging in criminal activities to exert his domination over the streets. The track, based on a loop of Joe Williams’ jazz vocal version of “Get Out My Life, Woman,” is one of three songs on Live and Let Die produced by the Trackmasters. The production crew got its start working with Chubb Rock and his affiliates, and was still a couple of years away from linking up with Bad Boy Records to produce the Notorious B.I.G.’s debut single “Juicy.” On Live and Let Die they provide a nice jazzy and soulful balance to Jinx’s largely chaotic production. But here on “Ill Street Blues,” G Rap still shines the brightest, delivering lines like, “I shake a schmuck just to make a buck /Then I break a duck and if the duck got to get bucked then I don’t give a fuck / Hyper as a sniper piping n*****s like a plumber / Cold vicking and sticking up the ones that run the numbers.”

Live and Let Die is at its strongest when G Rap explores the devastation that crime has on impoverished neighborhoods, contributing to an even greater hopelessness in these communities. On “Home Sweet Home,” G Rap describes dozens of quick scenes occurring on the drug and crime-ravaged blocks of New York City, using impeccable lyrical precision and complicated rhyme flows. He raps, “Can’t sleep, cause the streets are filled with danger / Miss, your little daughter's a swinger, you can't change her / She left with a stranger, inside a drug dealer's party / Now off to the morgue, to go identify her body.” On “Crime Pays,” G Rap explores the underlying political and social issues that create this environment and drive a disproportionate amount of inner-city residents toward lives of crime.

G Rap tackles the psychological effects of violence and poverty on two different tracks. The first is “Straight Jacket,” also produced by the Trackmasters. In terms of lyrical content, it sounds like it would be at home on Scarface’s first album, Mr. Scarface is Back. G Rap speaks as a patient describing his severe mental issues and how they’ve manifested themselves in extreme and deadly acts of violence. Besides hallucinating “pink elephants with little polka dots” and characters talking to him through the television, he describes killing people at random as a result of the voices swirling in his head. “I can’t escape this hell I'm in, not even in my dreams,” he raps. “I cover both my ears, because I’m sick of hearing screams.” The song lacks much subtlety, but subtlety and hip-hop don’t necessarily need to co-exist.

“Edge of Sanity” is more restrained in its approach, as G Rap speaks as a former stick-up artist struggling to stay on the straight and narrow, slowly losing his grip on his faculties in the process. G Rap begins by unsuccessfully trying to find a legal way to support his family as a convicted felon, but eventually succumbs to the pull of street crime. His eventual incarceration and loss of his family push him into madness, leading him to murder those once closest to him.

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about Kool G Rap & DJ Polo:

In the midst of all of this extremely heavy subject matter, G Rap does occasionally show flashes of humor, particularly on “Operation: CB.” In this case “CB” stands for “Cock Block,” as he spins a pair of tales about first his producer Sir Jinx and then a precocious toddler preventing him from getting his desired sexual gratification through their overall obliviousness. Sure, it’s juvenile, but G Rap’s palpable exasperation is entertaining.

G Rap also takes the time to engage in some top-notch braggadocio, displaying his verbal dexterity on tracks like “Go For Your Guns” and “’Nuff Said,” while still making it sound menacing. “Letters” carries a bit more of a lighter tone, as it’s designed to sound like an impromptu live lyrical display, with the DJ providing live scratches over a loop of Joe Tex’s “Give the Baby Anything the Baby Wants.” His skills are on full display as he raps, “Lead from my tec, come and step up and get your head wrecked / Wait a sec, you coming to see what's left? / I gotta catch my breath, rappers slayed / Or played like Jeff to the left.”

Live and Let Die also features a pair of sequels to enjoyable songs on Wanted: Dead or Alive to decidedly mixed effect. First is “Fuck U Man,” the even raunchier follow up to the already super-raunchy “Talk Like Sex.” If DJ Polo was to be believed, the song was originally conceived as G Rap’s ode to porn star Ron Jeremy, which is just weird if true. As it stands, the track, the third on the album produced by the Trackmasters, has G Rap spitting graphic sex raps to a sample of Bohannon’s “Save Their Souls.”

“Still Wanted Dead or Alive” is Live and Let Die’s second sequel, and somewhat misses its mark. It’s the type of super-violent track that would inspire Time Warner to decide against distributing the album, but it lacks any sort of direction. Sonically, it sounds like a clone of Ice Cube’s “The Product,” another Sir Jinx produced track, and pales in comparison to the album’s stronger fare.

The album closes with “Two to the Head,” where, over a slow, methodical sample of Funkadelic’s “Mommy, What’s a Funkadelic?,” G Rap is joined by Houston homies Scarface and Bushwick Bill, as well as Southern California O.G. Ice Cube. The track is one of the earliest collaborations of major label artists from East Coast, West Coast, and the South on one song. All four emcees do their thing, but Scarface, with the lead-off verse, may come the strongest, rapping, “So feel me drill me, put a bullet in my head / But you can't kill me, cause I'm already dead.”

Live and Let Die earned G Rap continued acclaim, even if it lacked a major label push in the Time Warner fall-out. While DJ Polo would fall to the wayside, G Rap would continue recording music as a solo artist. The dope 4, 5, 6 (1995) was the Cold Chillin’ imprint’s final long-player. The subsequent decades have seen numerous solo releases and collaborative LPs with different producers and emcees.

Live and Let Die might not be G Rap’s best album, but it’s certainly his most emulated. Its template was used by many artists, particularly NYC street rappers, throughout the ‘90s. But though many tried, few lacked G Rap’s lyrical depth and storytelling abilities. Even though the album was unfairly shafted by election year politics, its influence persists decades later.

As an Amazon affiliate partner, Albumism earns commissions from qualifying purchases.

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2017 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.