Happy 30th Anniversary to Nine Inch Nails’ second studio album The Downward Spiral, originally released March 8, 1994.

On August 9, 1969, Winifred Chapman stepped off her bus at the intersection of Santa Monica and Canyon Drive, already keyed up because she was late to her housekeeping job. Reaching the house at 10050 Cielo Drive, she noticed immediately what looked like a severed telephone wire hanging over the security gate. It concerned her, and she wondered if the gate would work, but as soon as she pushed the button, it swung wide open.

She noticed that someone had left the outside light on all night, which was unusual. She unlocked the service door, went inside, and picked up the phone in the kitchen. It was dead. She then walked into the living room, and that’s when she noticed the red splashes and puddles. The front door was ajar and beyond it, out on the lawn, she saw a body.

She ran out of the house and down the hill to the neighbors screaming Murder, death, bodies, blood! When the police arrived, they discovered what prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi would describe in Helter Skelter as “a human slaughterhouse.” The house and grounds, belonging to movie director Roman Polanski who was away in London, were strewn with the brutally slain bodies of Polanski’s pregnant wife Sharon Tate and the couple’s friends Jay Sebring, Abigail Folger, and Voytek Frykowski.

It wouldn’t take the LAPD long to trace the bloodbath to Charles Manson and his cult of hippie followers (a.k.a. “The Family”) at Spahn Ranch. Part of what helped them tie the murders to the Manson Family was the cult’s penchant for scrawling messages in their victims’ blood. On the front door of the house at 10050 Cielo Drive had been one bloody word: PIG.

Decades later in 1992, Trent Reznor visited a dozen Los Angeles houses in a day in hopes of finding a place to work on his forthcoming album The Downward Spiral. He then flew to Miami to record part of his Broken EP, and while he was there, he received the rental agreement for the place he’d settled on in LA. It came with a legal disclosure: the house had been the site of the Tate murder. So he reread Helter Skelter, and then unceremoniously moved into the house, where he’d live and record for the next year and a half. In a spirit of dark humor, he’d nickname the place “Le Pig” in honor of its front door—which he’d eventually take with him as a macabre souvenir before the house was razed.

Tori Amos, who visited Reznor at the Tate house to record a duet for her album Under The Pink (1994), was struck by its eeriness. “It’s a very spooky house, knowing what it is,” she recalled. “It’s just weird that when I was a young kid, we’d see the pictures in the book [Helter Skelter]—I had no idea that I’d ever be standing there, and standing there with Trent was kind of even goofier.”

Much like Amos’ confessional Under The Pink, which would arrive one month prior in 1994, Reznor’s The Downward Spiral was symbolic of “shedding skin, taking a layer off and analyzing it.” Perhaps that’s why Amos was one of the few guests Reznor welcomed at Le Pig. He’d moved there with the intention of living and working in almost total isolation. After all, he was pissed off at pretty much everybody.

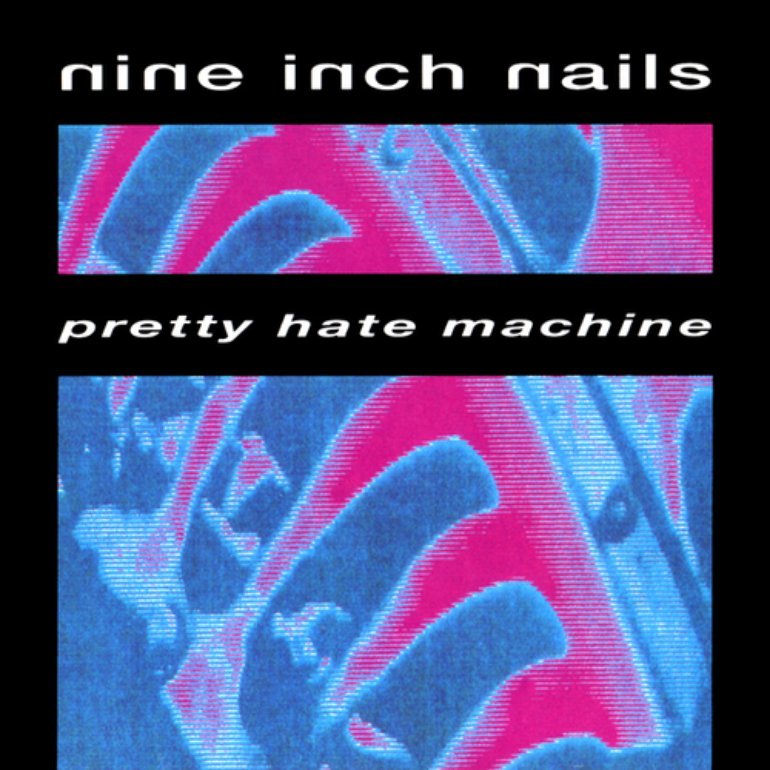

Reznor had started Nine Inch Nails in the late ‘80s shortly after moving to Cleveland and landing a job at Right Track Studios. During his off-hours, he toiled for a year recording demos that would score him his first record deal with label TVT in 1988. But during the recording of Pretty Hate Machine (1989), so began Reznor’s friction with TVT label boss Steve Gottlieb, who felt that Reznor’s decision to work with a slew of renowned producers (Flood, Adrian Sherwood, John Fryer, and Keith LeBlanc) complicated the recording process. Then, upon first listen, Gottlieb deemed PHM “an abortion.”

The tension reached a fever pitch as Reznor became increasingly critical of TVT’s support for the album after its release. There were drawn-out lawsuits and NIN halted any other recordings for the label. During a gap in touring, Reznor secretly began recording Broken, and his anger towards TVT continued to fester. As Adam Steiner points out in his excellent book Into The Never, “FUCK YOU STEVE” can even be spotted on a computer screen in a video for Broken’s “Gave Up.”

Watch the Official Videos:

Enter Jimmy Iovine, a producer who had become the head of his own label, Interscope, and who admired Reznor’s risk-taking and meticulous work ethic. Iovine went on the attack, calling Steve Gottlieb every single day for a year until TVT could no longer resist. In 1992, Iovine awarded Reznor what was rumored to be a seven-figure signing fee, and he sweetened the deal by also giving him his own imprint, Nothing Records. Though the Interscope/Nothing Records deal was a dream come true for Reznor, Gottlieb managed to secure a percentage of NIN’s ongoing publishing and sales, meaning Reznor wouldn’t be able to fully escape TVT. It blew the top off of Reznor’s rage.

Reznor had been mostly nomadic, touring constantly during his time in Cleveland. It left him with very few friends. Then, he suddenly found himself homeless after the breakup of a serious relationship, and so he decided he needed to hunker down for a period of introspection—or maybe just intense work—that would allow for complete oblivion. “I've become a workaholic just because I have nothing else to do,” he told RIP magazine. “As long as I keep working I don't have to deal with every other aspect of my life.”

He brought with him to the Tate house his hi-tech recording gear, having purchased a ton of new equipment. “If there was any sort of vibe then it was one of quiet, maybe sadness,” Reznor told Kerrang!. “But the nice thing about the house was that I wouldn’t leave it for weeks. Once I realized I hated LA, there was never any reason to leave. That perhaps added to the isolation and claustrophobia of the record.”

Reznor couldn’t have picked a better place to explore the depths of a mind whirling with gnarled nihilism, addiction, self-hatred, obsession, BDSM fantasies, and crippling depression. That was the true theme of The Downward Spiral: an unflinching look into the internal abyss. Still, Reznor was cognizant of not using his recording environment for cheap shock and horror. When he met Sharon Tate’s sister briefly one day, she asked him point blank, “Are you exploiting my sister’s death by living in her house?”

“For the first time the whole thing kind of slapped me in the face,” Reznor recalled to Rolling Stone. “She lost her sister from a senseless, ignorant situation that I don’t want to support. I don’t want to be looked at as a guy who supports serial-killer bullshit.”

Reznor inevitably ended up weaving some Manson themes—particularly the pig as a symbol—into The Downward Spiral. But, really, he was much more inspired by two records, David Bowie’s 1977 album Low and Pink Floyd’s The Wall (1979), than he was by the Tate house. Both albums captured their creators’ discomfort during difficult periods in their lives.

In the case of Bowie, he’d just relocated to Berlin in an attempt to free himself from an addiction to cocaine. With the help of Brian Eno, Bowie painted his dislocation in rich textures. The Wall, on the on the other hand, was about the feelings of disillusionment Pink Floyd experienced during their stadium tour for Animals (1977). At one point, Roger Waters spit in the face of a rambunctious fan, which led to exploration on The Wall of the alienated horror the band experienced as rock stars.

The Wall had offered Reznor comfort as a lonely, artsy kid growing up in rural Mercer, PA, surrounded by cornfields. So, he decided to create a broken main character, similar to The Wall’s Pink, to structure his album around. It would take its toll: “I wound up distorted, someone I didn’t know,” Reznor told Kerrang! in 1999.

The first time I heard The Downward Spiral, I’d, coincidentally, been stuck for several hours on the side of a mountain. It was early spring of ’94, and my friend Lara and I were downhill skiing when we suddenly came upon an expansive patch of black ice. It mocked us with its languid gun-metal gleam, its surrounding patches of yellowed grass like unctuous scabs on the filthy snow. FUUUUUCK! I screamed, my voice echoing through the Alps.

Lara and I managed to side-step our way back up the icy slope inch by excruciating inch. By the time we reached a skiable path, we were drenched in sweat and close to crying. When we finally got back to the bus for the long drive home, we’d kept our entire youth group waiting.

Chagrined, I plopped down next to my friend Jason as we pulled out of the parking lot in twilight. Before he fell asleep with his cheek pressed against the cold window, he’d taken pity on me and given me free reign of his CDs. I’d chosen his brand-new copy of The Downward Spiral. I was tired, but too wired to sleep, and something about gliding through the pitch-black night, the sole person awake while everyone else snored softly, made the experience of that album in my headphones entirely memorable and magical.

The Downward Spiral is dense like a wool blanket—wholly enveloping, at moments comforting, and at other times itchy and smothering. Reznor calls it “personal and ugly” and indeed it is. Though there are also moments of breathtaking beauty and subtlety. “There aren’t any obvious radio and MTV songs,” he boasted. Singles like the bloodily thrusting “March Of The Pigs” and the steely disco groove “Closer” were more of a re-education in what might be considered alt-rock or dance than a slide into easy listening. Reznor manipulated sounds using Pro Tools, distortion, samples, and all manner of unorthodox methods, like plugging a guitar directly into the mixing desk. The goal was often to make instruments sound not like themselves and more like a car door slamming, insects swarming, or even animals stampeding.

In her book on Pretty Hate Machine, Daphne Carr quotes a fan named Ric, a young man living in the Rust Belt, who manages to capture the anarchic mystery of listening to any NIN album: “I remember when I first heard it, I liked that I didn’t know what was going on. I liked listening to the Red Hot Chili Peppers and knowing there was a bass player, guitarist, singer, and drummer. With NIN, I was like, ‘How will the live show be? Is there going to be a guy rattling a box of chains, another with a trumpet, and someone with a garbage lid?’”

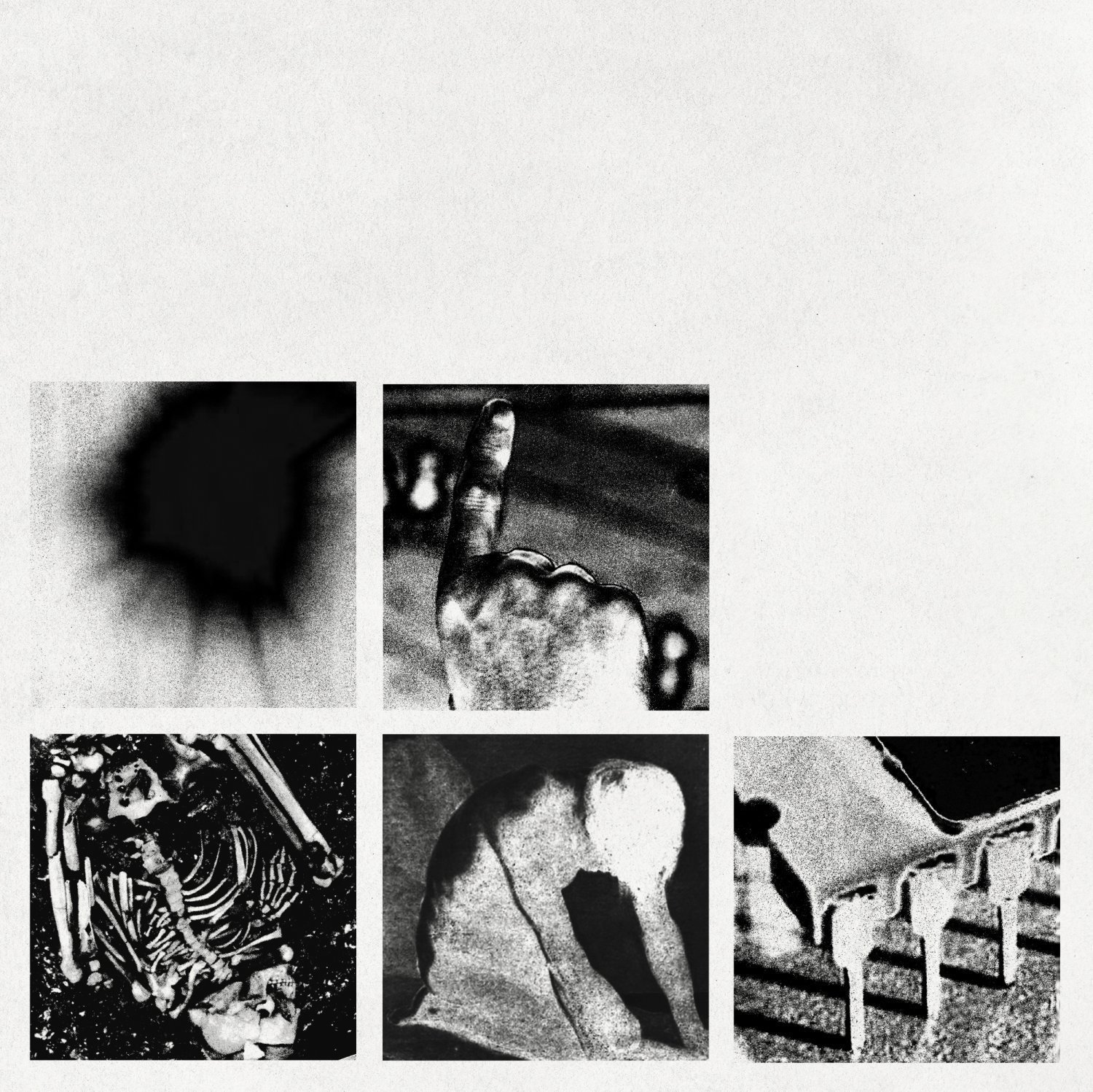

The Downward Spiral’s cover is a commissioned work titled Wound by British artist Russell Mills. Some of the key words Reznor provided for inspiration were: attrition, uncertainty, decay, organic, broken promises, lost dreams, and temptations. The resulting painting can be interpreted either as rusting metal or scabby skin. So it’s no wonder Daphne Carr draws a parallel between the American steel mills that ground to halt in the late 20th century, and Reznor’s incorporation of the machinery sounds of Pennsylvania and Cleveland into his music.

Though I grew up on an American army base in Cold War Germany (hence skiing in the Alps), I’d eventually end up going away to college in Bethlehem, PA. Once home to one of the world’s largest steel manufacturers, by the late ’90s Bethlehem Steel was a rusted-out carcass and the town was in economic distress. Nothing said “lost dreams” or “broken promises” quite like those rusty, smokeless stacks silhouetted like an apocalyptic Gotham against the night sky. It gave two meanings to “depression.”

The Downward Spiral begins with the sound of someone getting the shit beat out of them (a sample from George Lucas’ film THX 1138) and then a helicopter. We’re now inside “Mr. Self-Destruct” and its alternating screams and whispers. Just when the sonic assault makes you think you should side-step back up the icy abyss, an interlude tickles your ears like a moth’s wings—“You let me do this to you, you let me do this to you.” And then the assault is back, beating in every direction. The song references the needle in the vein, and we get the impression that this is someone battling with himself in multiple conflicting voices.

The next song “Piggy” starts out sauntering, Reznor’s voice seductive: “Hey, Pig.” But then the track melts into exhaustion as the narrator aches for a lost relationship. Though it’s rumored to be about a falling out Reznor experienced with former band member Richard Patrick, “Piggy” could also be about his breakup prior to moving to LA. The song’s languid sexiness paired with an airless, detached anger evokes the strangeness of a beautiful woman like Sharon Tate having “PIG” written in her blood.

Pumping and shimmery, “Heresy” is nihilistic in its screaming assertion that “GOD IS DEAD AND NO ONE CARES.” Then, Reznor switches to a Prince-like falsetto just short of a tongue flick in your ear. The album then transitions into punk-rock chaos with “March Of The Pigs” full of cabaret piano, zigzagging noise, and muffled whispers. “March” evokes a blind following, and possible cannibalism—“bite, chew, suck (away the tender parts)”—among dumb, egotistical animals.

The sex, self-hatred, and angry atheism comes to a head on the slinky, sadomasochistic “Closer” with its unforgettable chorus of “I want to fuck you like an animal” (it’s since become a strip-club anthem). Like every hormonal teenager, I probably named this song as my No. 1 at some point, but it’s since been replaced by the stomping “Ruiner” with its oddly subtle sounds of rewind and jazzy sax-iness.

On “The Becoming,” we get the sound of a rusting hulk roaring to life—“I beat my machine, it’s a part of me.” Reznor sings about becoming less human, his process of descending the spiral breaking him but also making him impervious to pain. On the next track “I Do Not Want This”, its looping drums supplied by Jane’s Addiction’s Stephen Perkins, the narrator detaches entirely from himself and his slow implosion begins.

The brash and wild “Big Man With A Gun” critiques gun violence and toxic masculinity. Then, the entirely instrumental “A Warm Place” provides a shimmery glacier of synth-y reprieve—though Steiner points out that it likely represents a place “where the narrator finally feels secure in his isolation, unreachable by the other voices.” The track then bleeds into the half-instrumental “Eraser,” its second portion a screaming meltdown whereby the narrator begs to be put out of his agony. It’s a disturbing song of suicidal ideation, yet commendable for its honesty.

“Reptile” is another song of lust, one of obsession for a lizard-like she-devil. The track combines desire with self-hatred again, and sex is an exercise in inevitable revulsion. “‘Reptile’ is pure dread that conjures the image of having sex with one of the airbrushed mechanical monsters in a H.R. Giger painting,” observed Jason Pettigrew of Alternative Press.

Infused with an insect swarm, “The Downward Spiral,” although ambiguous, is widely believed to be the track where the narrator’s suicide happens, if it even does. Reznor had reservations about including the song. “I think the worst thing in the world would be someone hearing this record as an endorsement of suicide—it is absolutely not that; it’s a moment that worked in the context of the story being told on the record,” he told Request magazine.

The sparse final track, “Hurt” can either be seen as an elegy, or a moment of reflection where the narrator, alive and safe, regrets his self-destructive urges. In an odd turn of events, the song would become more famous as a Johnny Cash cover. In 2002, Cash’s weather-worn voice imbued the song with further wisdom and, ultimately, survival.

Though the creation of The Downward Spiral nearly broke him, Reznor finally addressed his depression and addiction issues in 2001. The catalyst came when David Bowie, one of the inspirations for the album, asked Reznor to tour with him in the late ’90s and Reznor became increasingly ashamed of the person Bowie was getting to know. So he went to rehab.

“A few years later, Bowie came through LA and I’d been sober for a fair amount of time. I wanted to thank him in the way that he helped me,” Reznor recalled. “And I started to say, ‘Hey listen, I’ve been clean for …’ I don’t even think I finished the sentence; I got a big hug. And he said, ‘I knew. I knew you’d do that. I knew you’d come out of that.’”

Listen: