Happy 65th Anniversary to Muddy Waters’ live album At Newport 1960, originally released November 15, 1990.

It feels like my entire cultural year has been building toward writing this piece.

I’ve never felt especially connected to any zeitgeist, given my proclivity for keeping my cultural passions in my own little bubble. But social media has, to some extent, changed that. Through my writing here, I have connected with people who share the same passions and interests as me and I feel much more part of something, despite always holding a little something back for myself.

When Ryan Coogler’s Sinners appeared earlier this year, I saw it at the first opportunity and was, like countless others, blown away by his artistry. But beyond the visceral thrills and the multi-layered tale of his unique vision, I emerged into the night, hopeful that it might usher in a renewed interest in the music that first grabbed me as a teenager.

I’ve written before about hearing Robert Cray’s guitar through my sister’s bedroom wall and being enraptured by it. It led me to dive headlong into discovering as much as I could about the blues and, boy, did I commit. When I was thinking about what I could make the subject of my sociology dissertation, I knew it had to be more interesting to me than the brain-numbing topic I’d chosen for my appalling geography one. So, I wrote about whether blues music could be considered an authentic social document. I spent hours transcribing lyrics and comparing them to books and articles about the social conditions of the US at the time. And, spoiler alert, of course it fucking is—the blues is partially the unvarnished truth of a shitshow that still plays out today, in all its abject horror.

Last Christmas I received a gargantuan pile of books, most of them about music and culture. Among them was Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other Suns. I’d read Caste after watching the film adaptation by Ava Duvernay and was ready to dive into a subject that had occupied a good deal of my dissertation. As I write this, I am racing through this wondrous work and wishing it had been written in the years before my aforementioned university work, so rich it is with the context and lived experiences of Black migrants from the South heading for the supposed better life in the North and on the West Coast.

All of which leads me to an album that could be said to be one of the most important of all time by an artist who epitomizes the Great Migration to a tee. Born in Rolling Fork, Mississippi in 1915, McKinley Morganfield became known to one and all as Muddy Waters when he was old enough to toddle into the dirty creek behind his back porch. In August 1941, Waters recorded his first song for famed field ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax, but just two years later Waters was joining the hundreds of thousands of Black people leaving the brutality and horror of the South for the industrialized cities of the North.

Listen to the Album:

When Waters arrived in Chicago in 1943, Big Bill Broonzy took him under his wing (as he had done with so many others) and guided him towards becoming perhaps the most important artist in bridging the deep Delta Blues and the slicker, urban and electric blues that Chicago especially became known for. While many early blues songs recorded in the North pined for the old lives the artists had known, soon it became clear that audiences wanted new songs affirming the life choices they had made in fleeing the South.

Waters specialized in something that was equally necessary and simultaneously brave—he unleashed a virile, strutting Black masculinity at a time when it was dangerous simply to be a Black man. By the late ‘50s though, the blues was beginning to feel the hot, insistent breath of rock and roll on its neck. Audiences felt the thrill of the newly emerging rock and roll at the same time that Sam Cooke and Ray Charles (and others) were stirring souls with music that fused blues, jazz and gospel. The market was crowded.

In 1960 though, Muddy Waters reinvigorated the blues with the performance and subsequent release of his spot at the 1960 Newport Jazz Festival. Waters had upset those most annoying of musical fans—the purists—when he had plugged in his electric guitar and let rip with his band in the late ‘50s. Saint Etienne co-founder Bob Stanley wrote in Yeah Yeah Yeah: The Story of Modern Pop that Waters had “shocked the beatnik purists at St. Pancras Town Hall by playing electric guitar” before going on to say that some even booed. “Beatnik purists”—the caucacity.

Listening to At Newport 1960, it seems almost unthinkable that anyone would be anything less than blown away by the sound of the blues exploding so impressively. Alongside Waters’ monumental vocals and guitar playing are Pat Hare (guitar), Andrew Stevens (bass), Francis Clay (drums), James Cotton on harmonica and Otis Spann on piano. The rhythm section is a tight as you’d imagine but the piano playing of blues legend Spann and Cotton’s harmonica light up so many of the tracks.

There are three monster hits that have become part of the Blues pantheon here, given all the life and energy that the prowling majesty of Waters can muster. “I’m Your Hoochie Coochie Man”, “Baby, Please Don’t Go’ and “Got My Mojo Working” have been covered and imitated by a host of white rock and blues bands, but nothing comes even remotely close to matching the swagger of Waters and the musicality of his band. In their hands they are fundamental cornerstones of the blues canon, with Waters at his imperious best—a brooding master of the carnal.

Of the other songs, perhaps the most notable is ironically the one that doesn’t feature Waters’ vocals. The set was closed out by an impromptu composition by the festival director—none other than Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes—called “Goodbye Newport Blues”. Here, Otis Spann leads the vocal and it is just as rollicking and butane-filled as the others that rub shoulders with those earlier classics.

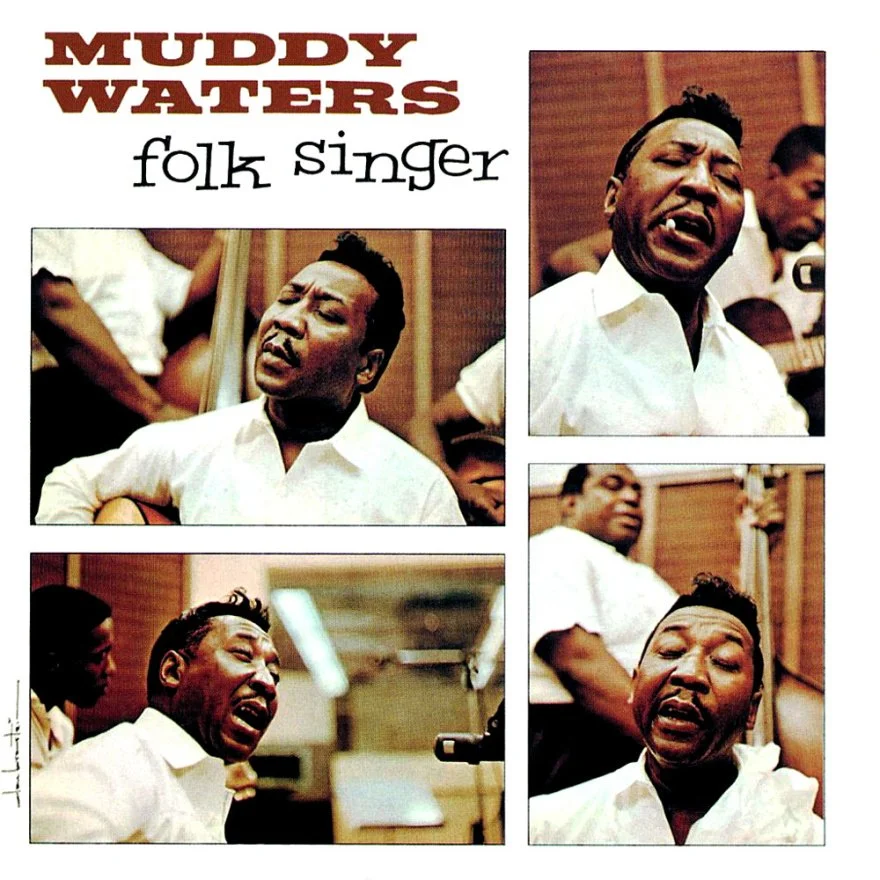

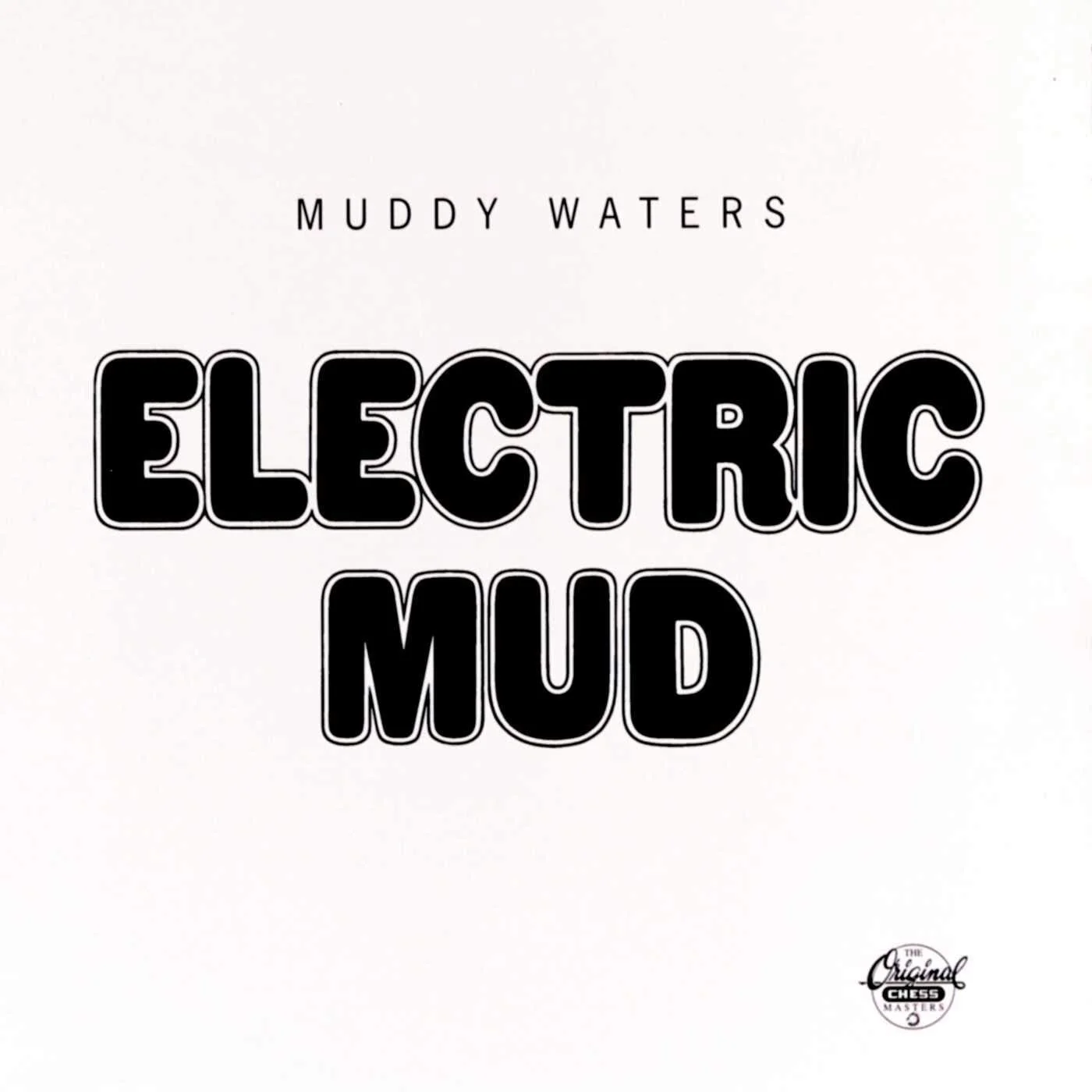

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about Muddy Waters:

The importance of this album, beyond the vim and vigor of the exceptional performance lies in the impact it had on the bunch of burgeoning blues bands that the UK was home to. Of course, it is not inherently interesting just because white guitarists like Alexis Korner were influenced by Waters’ Newport set, but rather because it helped set the ball rolling on the reinvention of blues music as rock music. Though the British bands would definitely invigorate the scene and broaden its appeal, their pyrotechnics were put in the shade by the astronomical talents of Jimi Hendrix, who took the blues to another planet.

As well as inspiring a British invasion of the charts stateside, a younger generation of blues players from the US also benefitted from Waters’ expertise. Among them, aptly, was Buddy Guy. Born 21 years after Waters (and now 89 years old), he is perhaps the last of the bluesmen and women who made their way from the South (Louisiana in Guy’s case) to the North in search of a better life during the Great Migration and, as such, is living testament to the shameful history of the United States in the Twentieth Century and the Black musicians who shared their pain, heartache and joy along the way. A history that Langston Hughes put so succinctly in his poem “The South” in June 1922:

The lazy, laughing South

With blood on its mouth . . .

Passionate, cruel,

Honey-lipped, syphilitic –

That is the South.

And I, who am Black, would love her

But she spits in my face . . .

So, now I seek the North –

The cold-faced North,

For she, they say,

is a kinder mistress.

Listen: