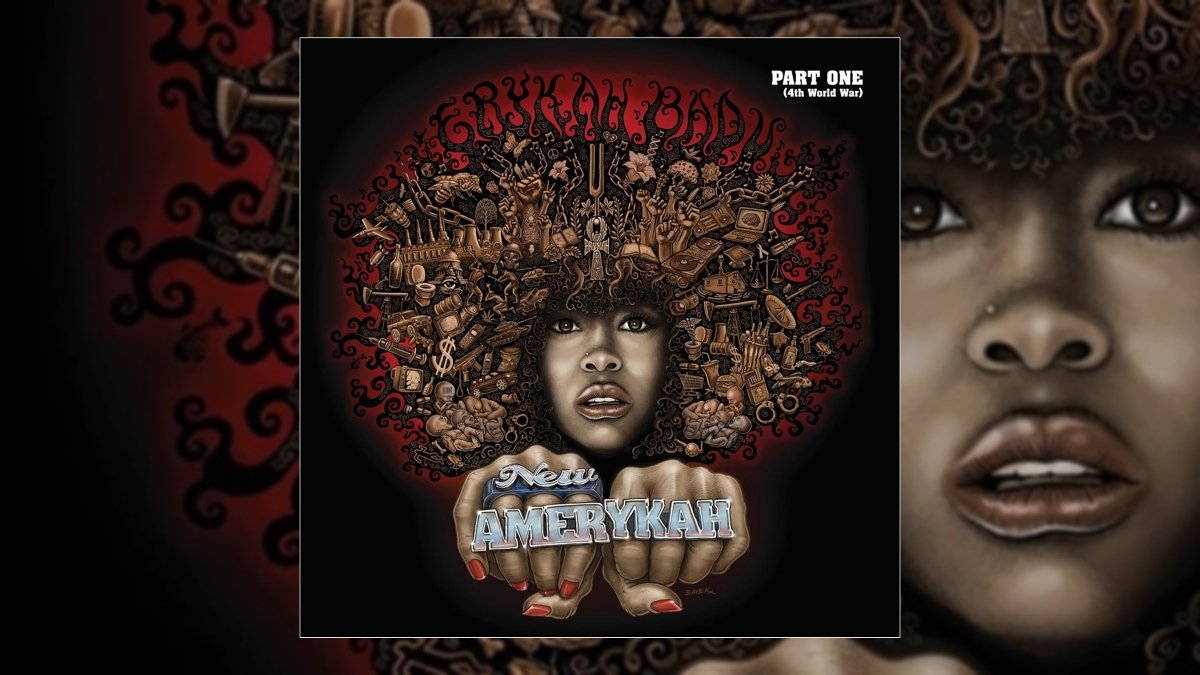

Happy 15th Anniversary to Erykah Badu’s fourth studio album New Amerykah Part One (4th World War), originally released February 26, 2008.

I don’t have to tell you things aren’t good. Everybody knows things aren’t good.

I don’t know what to do about the recession and the inflation and the crime in the street. All I know is that you’ve got to get mad.

“Twinkle”

Erykah Badu’s fourth studio album New Amerykah Part One (4th World War) was released in early 2008 but the circumstances, subject matter and processes that shaped the album were entirely different from those that had come before it. Consequently, it marks the onset of a new phase in her career where the self-confessed “analogue girl in a digital world” (from “…& On” featured on her 2000 album Mama’s Gun) ventured out into the 1s and 0s of 21st Century musical production techniques without sacrificing the fully-rounded artistry of her previous efforts.

At the root of the brilliance contained within New Amerykah Part One is an extended period of writer’s block that followed Worldwide Underground (2003). She had never been the kind of artist to churn out an album every year (it had been three years between each of her albums, discounting her live album from 1997), so with children to raise and life to be fully lived, the music always came at her own pace.

In the wake of Worldwide Underground, she embarked on the Frustrated Artist tour, whose name could not have been more apposite. The epithet “Queen of Neo-Soul,” though well-meant, was a weight upon her shoulders that constricted her artistry and self-expression (as she explained to the New York Times in March 2008). A year later in 2004, her family grew once again as she gave birth to her daughter Puma Rose, meaning motherhood became the priority once again just as it had with the birth of her son Seven Sirius soon after her debut album Baduizm in 1997.

But beyond family life, Badu began to struggle with writer’s block—what was there to write about anymore? What did she have to say about the world? The artistic malaise was lifted by a gift that brought her back to creativity and into the digital age, and once the creativity began to trickle, it soon turned into a raging torrent. No sooner had she been given a computer by Questlove (that constant keystone of Black music), than she was able to trade ideas with her musical kinfolk. Questlove, Q-Tip and J Dilla all sent her ideas electronically, while her son, Seven, introduced her to GarageBand and the endless possibilities to record herself it offered.

Soon enough, she reveled in the creative freedom the technology brought. She could instantly record ideas and sing freely at home in between motherhood’s demands. She wrote and recorded around 75 songs in under a year and the creative shackles were well and truly thrown off. The vast majority of her past catalogue had been explorations of self and the heartbreaks and joys associated with romantic love, but here the subject matter was something else entirely.

There had been moments of social commentary (such as “A.D. 2000” on Mama’s Gun), but here she found much more to turn her pen to. The Roy Ayers-produced opening track follows in the funk-fueled footsteps of the trailblazers of the 1970s, mixing an irresistible groove with lyrics that outline the betrayal of the notion of an American Dream by the rampant exploitative capitalism that underpins it: “Promise to you baby, anything you want you know I’ll buy / promise to you baby, you will never have to ask me why.”

Listen to the Album:

Later on the hyper-kinetic bounce of “Soldier” she played community organizer: “Baptized when the Levy broke/ we gone keep marching on / till we hear that freedom song / and if you think about turnin’ back / I got the shotgun for your back /and if you think about turnin’ back / I got a shot gun on ya back / (Harriett style).”

Meanwhile, “The Cell” covers the oft-told tale of drug dependency and its ravages on Black life and “Twinkle” is a stuttering, jittery call-to-arms and acts as a precursor to the cultural significance of what follows next. When Badu and Georgia Anne Muldrow composed “Master Teacher” (along with Shafiq Husayn) and penned the refrain “I stay woke,” they could scarcely have imagined the way “woke” has entered the collective vernacular in the way that it has.

Of course, given their understanding of the world, they may well have imagined the ways in which it has become bastardized and weaponized by white supremacist grifters in search of a pay day, its meaning distorted and twisted from its original intent of being alert to social injustice and the structural barriers to equality. The song’s repetitive meditative power remains unbroken by the distortion though.

None of which means that her personal reflections are absent from the album—the personal sits comfortably between the exhortations for community and comment on the state of the world. Nowhere is that more obviously signposted than on “Me,” which is a “State Of The Union” address for the United States Of Badu. It finds her tussling with growing older in the public gaze (“Sometimes it’s hard to move you see / when you’re growing publicly”) and the changes to her body (“This year I turn 36 / damn it seems it came so quick / my ass and legs have gotten thick, it’s still me”).

But the gut punch comes courtesy of “Telephone,” recorded the day after J Dilla’s funeral. The writing credits tell the story. Badu, Questlove and James Poyser created the atmospheric reflection on the loss of their dear friend and musical genius with lyrics inspired by a story Dilla’s mum told Badu. But those credits are unusual for this album, as it marks a break in the collaborators she predominantly worked with for the first chapter of her career.

Maybe inspired by the freedom technology afforded her or simply taken by the idea of working alongside different, varied musicians and producers, she expanded her circle beyond the archetypal “Soulquarians” who had helped shape the early part of her artistry.

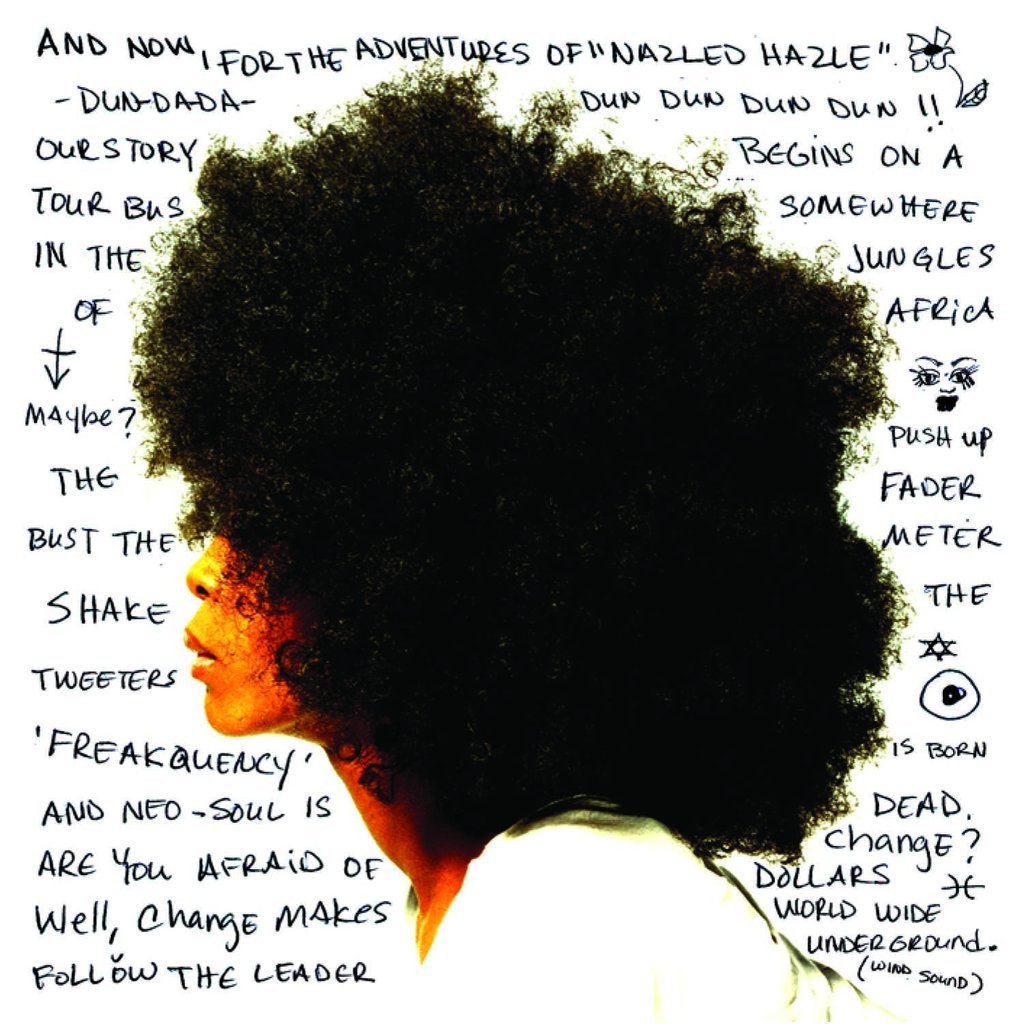

Instead, Madlib assisted with the transcendentally gorgeous “The Healer,” Shafiq Husayn (and, by extension, the Sa-Ra Collective) produced various songs throughout, and Thundercat applied his bass magic to several tracks too—all of which trumpeted a changing of the guard as far as Badu’s discography goes. The album’s artwork also took a decidedly new direction with artist EMEK designing a series of outstanding images that encapsulated the societal chaos swirling around Badu and her newly acquired role of digital musician amidst it all.

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about Erykah Badu:

If there’s one song that feels out of step with the rest of the album it is (perversely) the lead single “Honey.” The light, bright and bouncy single with its accompanying, award-winning video is an effervescent joy but it stands alone as quite different to the fare that followed it—I remember vividly the fractured feeling upon hearing the rest of the album with its (at times) dense social commentary as compared to the frothy wonder of “Honey.”

The turn to digital recording clearly did wonders for her productivity—the follow-up to New Amerykah arrived barely two years later in the form of New Amerykah Part Two (Return of the Ankh) (2010), making it the quickest turnaround between albums in her career. But returns soon diminished—it is now eight years since But You Caint Use My Phone(2015) and there are few signs of a return to the studio. With no new material to feast on, it makes it all the more important to enjoy the existing albums and this one certainly deserves time, effort and more than its fair share of appreciation.

LISTEN: