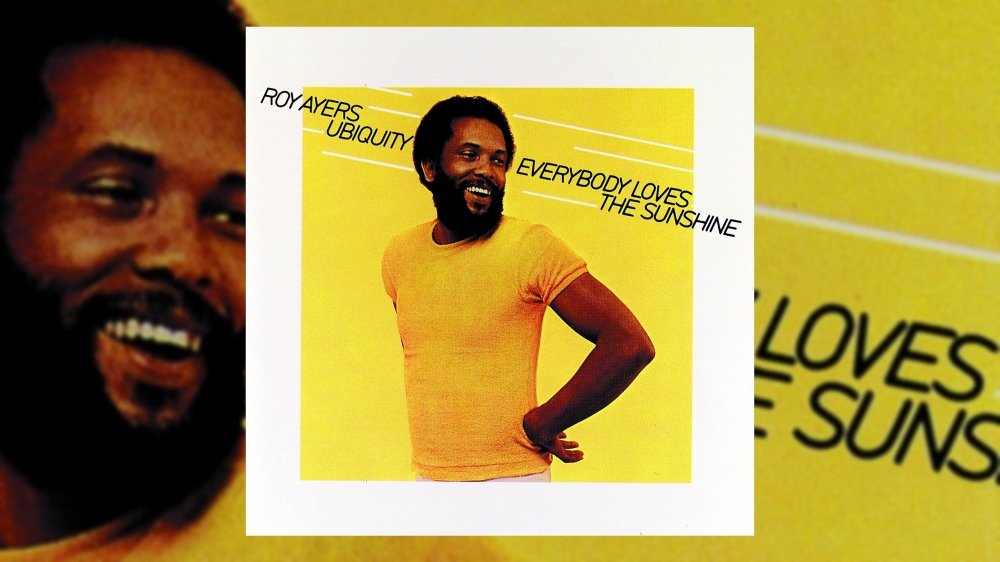

Happy 45th Anniversary to Roy Ayers Ubiquity’s Everybody Loves the Sunshine, originally released May 12, 1976.

“Just bees and things and flowers…”

While it’s true that everyone is entitled to their respective preferences and opinions, jazz criticism is one of those tough disciplines to pin down. With every aspect of jazz as an art form, the strong ambivalence towards its evolution, musical creativity and artistic innovation has often reflected more on the individuals who have romanticized jazz from a specific, subjective standpoint.

Instead of studying the cultural, social, and political context that shapes jazz music, purists immediately perceive themselves to be experts of the craft, crying foul on what they feel isn’t permissible to the culture. There is alarming tension between critics who lack the complete understanding of the core principles that run through jazz music and its purveyors who have created their interpretations of the music solely from their own cultural lenses. No other subgenre in the jazz realm better exemplifies how deeply devastating jazz criticism had become by the 1970s than jazz-funk fusion.

During the mid-to-late 1960s, traditional idioms that defined the jazz landscape were beginning to lose their commercial distinction in the marketplace, as musicians strived to take their artistry to new dimensions and heights. A young, diverse and hip audience arrived at the forefront of everything that had become commonplace in the musical landscape.

Culturally, a new era dawned, when unbridled pride and Blackness galvanized the Black community. In favor of embracing Black consciousness and garnering wider success, established jazz musicians became invested in appealing to the ears and minds of young, bold, and beautiful Black America. Unique fusions of sound emerged, amalgamating adventurous slices of soul, funk, rock, and several other idioms.

In the 1970s, jazz vibraphonist Roy Ayers, was an anomaly. With umpteenth years in the music business and a large output of long players under his belt, the San Francisco native became one of the most visible and scorned figures among jazz circles. It was obvious that he was an accomplished musician in his own right, but most importantly, he was at the helm of a crucial transition that took place in jazz, where funk and soul gave way to heavily percussive, African-infused polyrhythmic sensibilities.

While he was an established vibist that employed a major hard bop approach to his style, Ayers’ signature blend of hypnotic dance grooves, jaunty backbeats, and infectious vocal interplay became the most distinctive elements of his musical approach. In signing with Polydor Records and forming his own collective of musicians, Ubiquity, with jazz-rock heavyweights like Billy Cobham and Sonny Fortune in 1970, he punctuated his earthiest and most adventurous excursions in the jazz fusion universe.

Listen to the Album:

During that stretch, he released pioneering records that would go on to define much of the acid jazz movement and neo-soul world two decades later, such as 1971’s Ubiquity, 1972’s He’s Coming, and 1973’s Red, Black and Green and Virgo Red. Perhaps his most revered contribution to jazz-fusion came with his masterful 1973 score to the blaxploitation film Coffy, where he configured an unprecedented balance between trippy funk and lush cinematic soul.

Something shifted soon after, though. Crossover became a major part of Ayers’ musical aspirations and he remained a rather prolific entity, catering his music to the same commercial R&B audiences who cherished major figures like Stevie Wonder and Earth, Wind & Fire. Several argued that Ayers, similar to other jazzmen who strived to crossover during this highly controversial period in jazz, was nothing more than a business man who capitalized on dance-friendly and streetwise R&B, and branded it as “jazz music.”

While economic gain was a mainstay for musicians in the crossover jazz era, there’s one vital thing that Ayers sought out to accomplish. Like Herbie Hancock, Donald Byrd, and George Duke, Ayers wanted to draw masses to the jazz stratosphere. Plus, he was very much a musical maverick who was influenced by everything under the sun. Why not be a non-conformist and expand all the capabilities that the genre had to offer? True evolution is realized when one moves beyond conventionality and defies categorization anyway, right?

As if the title of his 1974 effort Changing Up the Groove didn’t hint at this direction already, Ayers was consciously evolving his musical prowess, employing an accessible edge to his ubiquitous fusion of jazz, soul, and funk, a la Byrd’s controversial crossover recordings for the Blue Note label. While his refined musical style wasn’t a sharp departure from the eclecticism of his earlier Polydor-era recordings, Ayers certainly kept his ears and eyes open to all of the trends and idioms that ran through Black popular music throughout the mid-1970s.

He would constantly change the line-up of his Ubiquity band, with a pronounced female vocal presence that often suited his distinctive smooth vocal style. During 1975, he released two transitional albums, A Tear to a Smile and Mystic Voyage, which showcased his refined approach, expounding on his flirtation with R&B, dance and funk leanings, while largely confounding the jazz community even more.

At every cost, he would hit bigger stakes on 1976’s Everybody Loves the Sunshine.

It’s not quite difficult to fathom how and why Ayers’ fourteenth release struck a chord with many, becoming his most commercially successful and popular work. While it’s obvious that Everybody Loves the Sunshine wasn’t a stylistic deviation from the last couple of albums he released during the mid-1970s, it certainly wasn’t a step forward. Strangely, it couldn’t even be considered an effort of regression either. Recorded during 1975 and 1976 at Electric Lady Studios in New York and Larrabee Sound Studios in Hollywood, Ayers was certainly on a creative hot streak and showed no signs of diminishing his distinctive approach for Sunshine.

The album’s ultra-nostalgic artwork sports several shots of Ayers, grinning and chilling on an apt sun-screened yellow background. It screams 1970s camp and crossover in the same breath, but it’s inviting when you glance it. This was largely an album that could sit squarely next to many soul and funk masterpieces, as well as the mighty fusion works that defined the era.

Even during its hollow moments, Ayers’ musings on unity, spirituality, love, and of course, the world were prominent themes. The combination of slickness and grittiness captured in each of its grooves was a testament to his masterful commitment to craft his version of “the funk” from its own dimension, never once lessening or compromising its power.

The musicality possessed a certain high energy and mellowness that Ayers and his Ubiquity band were known for by that point, but everything was played with precision. A more nuanced focus on electronics and synthesizers (compellingly done by Ayers and Phillip Woo) is apparent here as well. There is no doubt that this album was destined to set many disco clubs and parties into a frenzy, while dropping life-affirming doses of knowledge to the People all in the same stroke.

The album’s opening track “Hey, Uh, What You Say Come On” drifts in the center, as if someone flipped it on a radio transistor. A hip invitation to dance, there’s nothing more to the song’s disco-laden groove than Ayers tirelessly chanting the titles in repetition. It’s quite silly and trite, but the cosmic groove is undeniably infectious, with heavy funk improvisation running through it. The peppy instrumental “The Golden Rod” follows, with Ayers playing his vibes with great precision and ease. There’s a certain breeziness to its jazz tonality that makes the song a refreshing complement to a laid-back summer day.

No stranger to covering material, Ayers tastefully covered Gino Vannelli’s 1975 song “Keep on Walking.” Retaining the original’s moody and calm atmosphere, Ayers’ smooth-yet-fragile tenor caresses each lyric with a tenderness that is hard to resist, with Ubiquity’s female vocalist, Chicas, backing him. Although the song is dedicated to the travails of moving on from a love affair, “Keep on Walking” exemplified Ayers at the top of his balladeer game, composing an ethereal slow jam with such care and diligence.

“The Third Eye” is a cerebral, six-and-a-half minute meditation on inner-peace, cosmic spiritualism, and truth that Ayers knew all too well. With a deep emphasis on jazz improvisation and quiet storm qualities, the spacey ballad remains one of the album’s most enduring highlights.

Bubbly funk slices of anti-astrological philosophies and pleas for positivity and unity are found on “It Ain’t Your Sign It’s Your Mind” and “People and the World,” which can be seen as something of a prelude to the album’s most definitive song as well as Ayers’ seminal standard.

Personally, I have yet to find a person who hasn’t at least recognized the irresistible rhythm and chorus of “Everybody Loves the Sunshine.” You would be hard pressed to spot someone who hasn’t heard it in the form of a hip-hop sample or some other media entity, as it remains one of the most utilized and infectious grooves ever made. Nonetheless, whenever it comes on, everything stops. Time fades away. Somehow the subtle and easy-going charm of the song instantly puts you squarely in heart of the summer. All your senses are tapped. Its soft piano twinkles, plaintive guitar, and steady congas intertwine with the woozy ARP Odyssey synthesizer flourishes as gently as an afternoon stroll on a lakefront, while you soak up the humidity and scenery.

The moment Ayers and his female counterpart Chicas croon, “My life / My life / My life / My life / In the sunshine,” you’re immediately swept up in the aura of sweltering heat from the sun’s radiant rays. Coincidentally enough, there was no notable vibe solo from Ayers at any moment of the groove. The true vibe is in how Ayers manages to inject so much personality into his conjuring of summertime into a four-minute pop song. With a hypnotic and dreamlike melody that is as sweet as nectar to a bee, “Everybody Loves the Sunshine” became an endearing anthem to not only the laid-back atmosphere of summer, but people living in pure tranquility.

Given that the title track resonated with several from Ayers’ R&B base and the pop community, Everybody Loves the Sunshine obviously sent many flocking to stores when it arrived in 1976. Commercially, the album peaked on the Billboard 200 albums chart at #51, while reaching #10 on the R&B albums chart and #5 on the Jazz albums chart. While Everybody Loves the Sunshine is not what I would consider his finest record, it certainly stands as one of the glowing examples of Ayers’ ubiquitous brand of “universal” music. It was the culmination of everything Ayers wanted his music to achieve. It was conceived for the People, by the People.

The universe has raised Ayers’ profile as a massive legend, whose musical legacy permeates through everything far beyond the conventions of jazz. The jazz world may have been forever divided when it came to crossover, however, there’s no doubt that Roy Ayers caused several tidal waves in the music world over the course of his entire career. Forty-five years later, the Sunshine still shines and it always will. Certainly, we have Mr. Ayers’ evolution to thank for it all.

LISTEN: