PJ Harvey

I Inside The Old Year Dying

Partisan

Listen Below

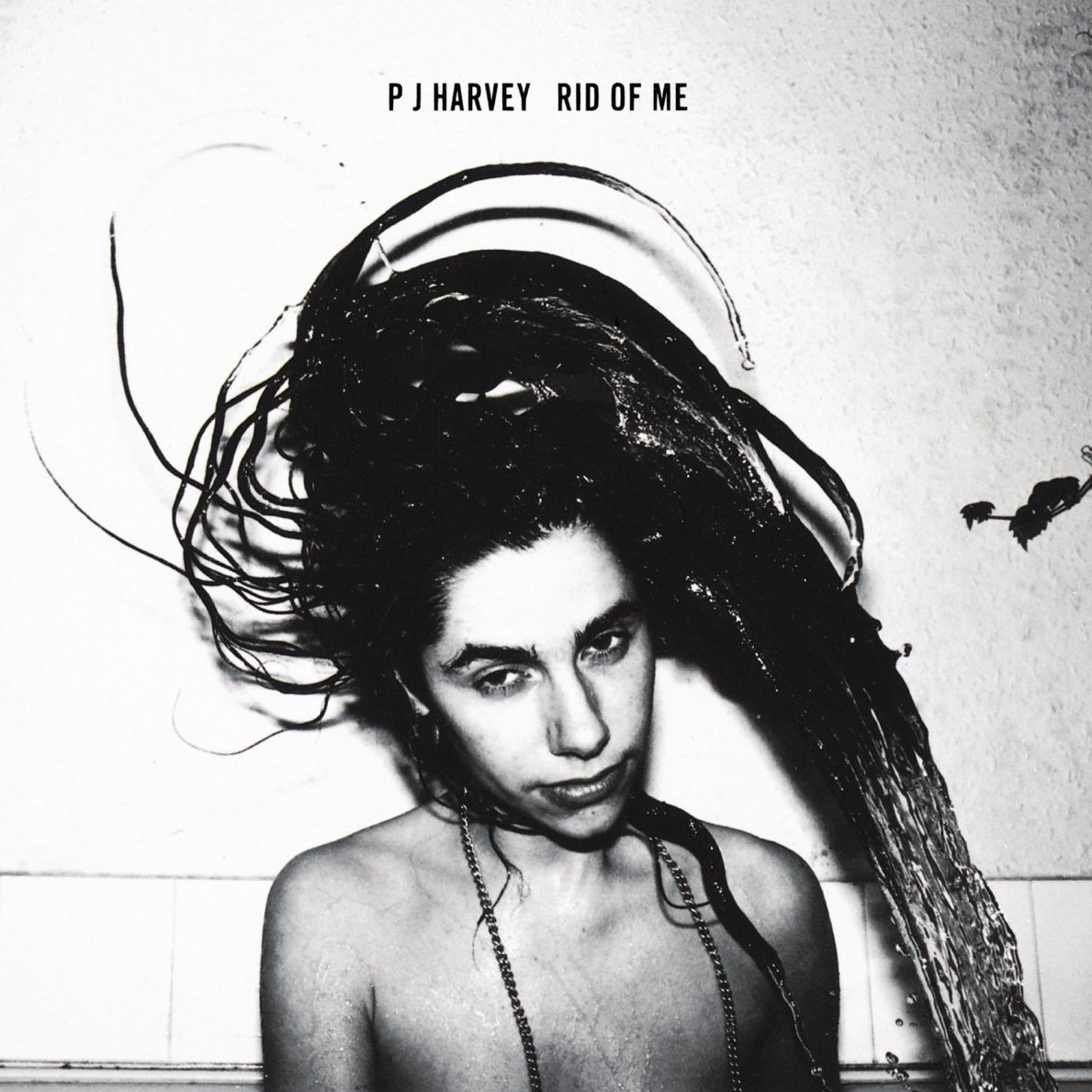

My all-time favorite PJ Harvey clip comes circa 1993, when she went on The Tonight Show with Jay Leno to promote Rid Of Me, one of the most celebrated albums of the year. After performing an electric solo version of the title track, she steps daintily onto the stage to answer Leno’s questions. “You still live on a farm in England, right?” he inquires. “I do, yes,” she says politely. “I still live on a farm with my parents. I live in Dorset, which is the southwest coast of England.”

Leno nods. “So you still go back and do the chores?” Harvey smiles shyly and answers, “It’s a sheep farm, so when I’m home I mostly help with dipping the sheep and I help with wringing testicles and things like that.” “Wringing testicles?!” he gasps. Harvey studies him, amused. “You have to wring the testicles with a rubber band, and after about two weeks they drop off,” she explains, a sly smile playing at her lips. Leno responds with the requisite (giggling) horror, and suddenly we’ve gained deeper insight into the slip of a girl in a gold lamé dress who has just belted out (albeit in the sexiest way), Yeah, you’re not rid of me / I’ll make you lick my injuries / I’m gonna twist your head off, see.

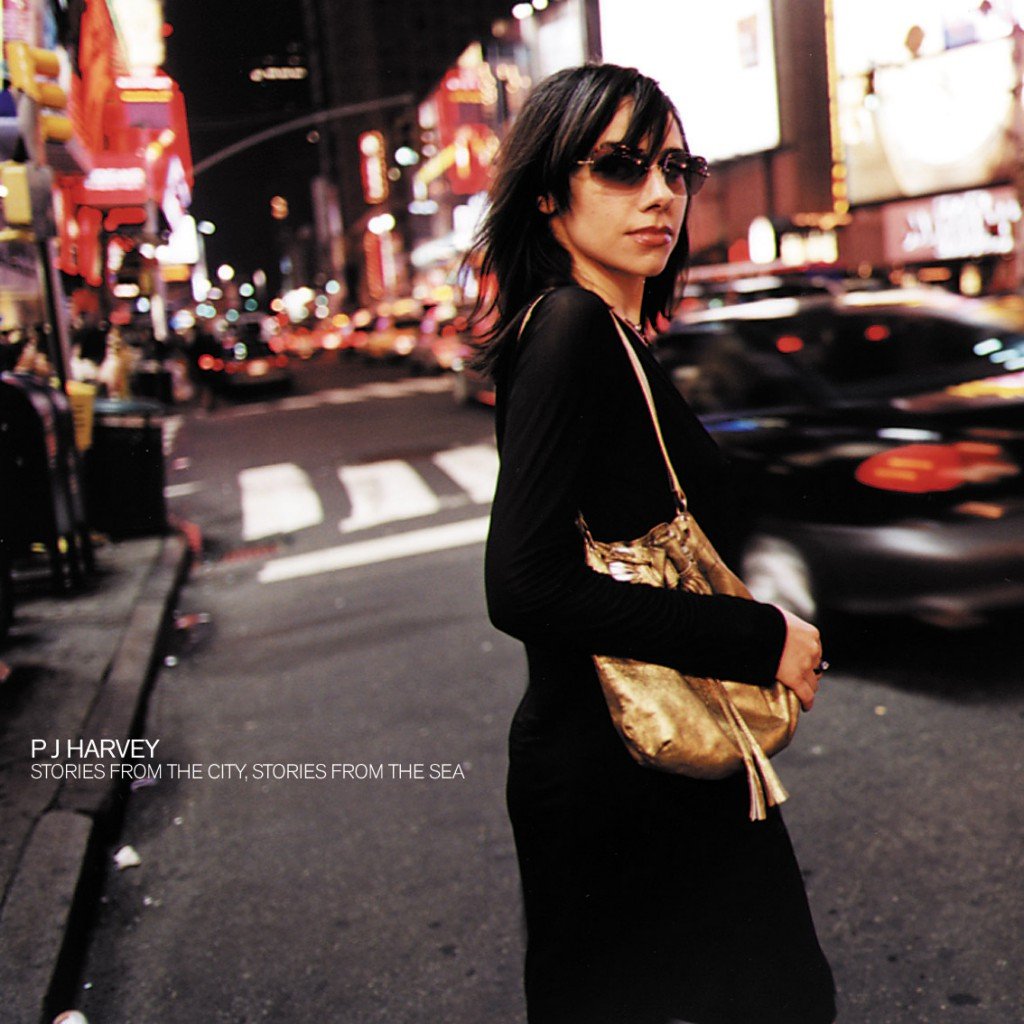

As the only artist ever to win two Mercury Prizes, Harvey has grown into a world-class polymath with numerous acclaimed albums in her repertoire, and yet she’s continued to shirk the bustle of fame in favor of a quiet life in her native Dorset. For previous albums, she’s written about New York (Stories From The City, Stories From the Sea), World War I-era England (Let England Shake), and Washington D.C. and Kosovo (The Hope Six Demolition Project), but she’s never taken us, at least not directly, on a journey to her rural home.

This week, she has released her tenth album I Inside The Old Year Dying, based on 12 poems from her acclaimed novel Orlam, published last Spring after a three-year mentorship with Scottish poet Don Paterson.

Orlam is a surrealist narrative poem that takes place in the fictitious Dorset village of Underwhelem in the year after its heroine, nine-year-old farm girl Ira-Abel Rawles, has suffered the loss of her beloved pet lamb to murderous rooks. The incident foreshadows a savage cruelty at the heart of the village, and Ira retreats to a world of ghosts in the woods for comfort and reprieve. It’s there that she meets Wyman-Elvis, a ghost-soldier with his throat slit, and Ira develops a schoolgirl crush as one would on a rock star, or (as the ghost’s name suggests) the King himself. “Love Me Tender” is Wyman-Elvis’ siren song and, as we witness each assault, betrayal, and heartbreak perpetrated on Ira-Abel by her family and the townspeople, we come to understand that this is what she desires with an ache beyond words—to be loved, simply and tenderly.

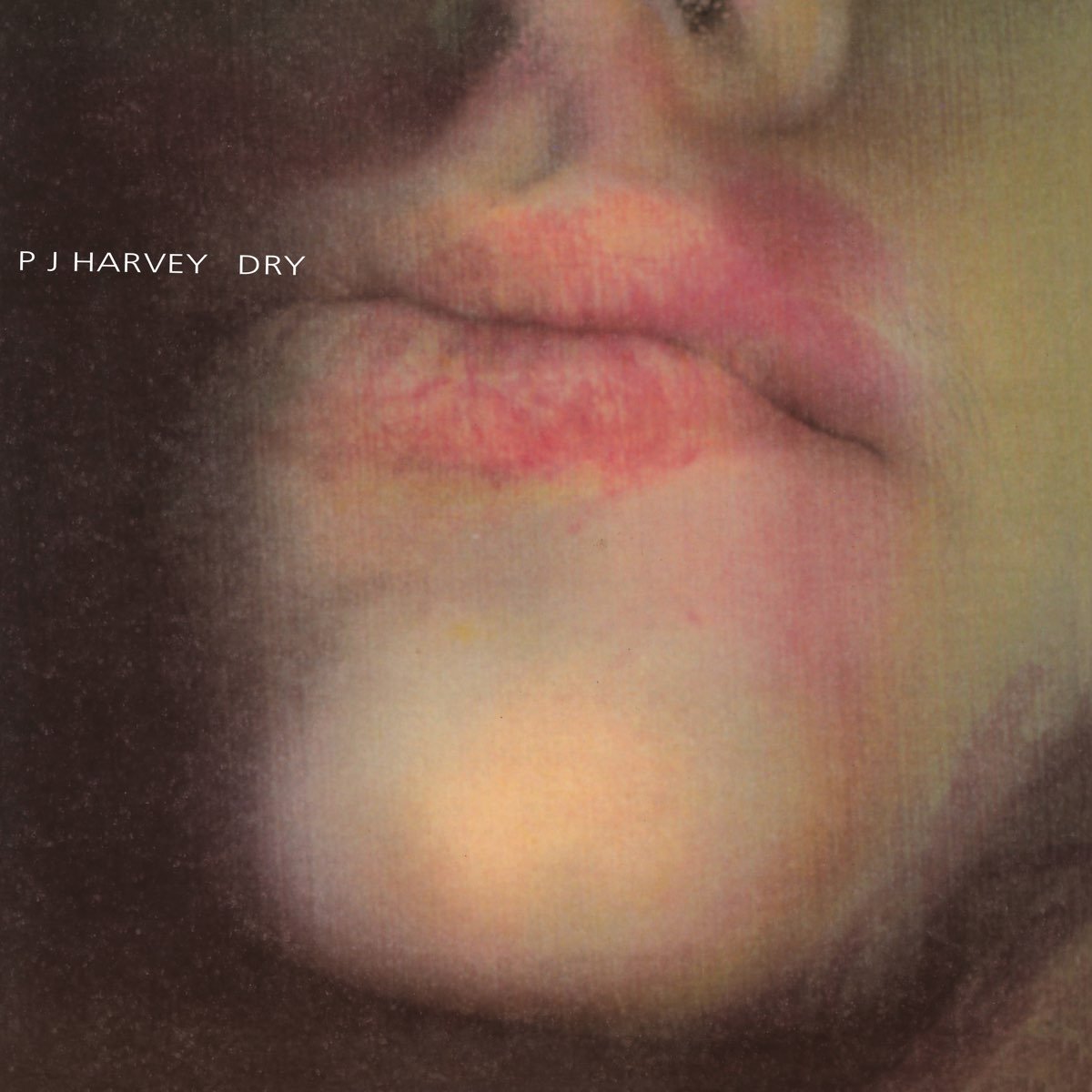

Though Harvey has been drawn to the dark places ever since Rid Of Me (and, arguably, her 1992 debut Dry), it was through her research of World War I for 2011’s Let England Shake that she decided to take on writing of this ilk. “I was so absorbed with reading war poets—not just First World War, but across all wars—and I found the need to put very ugly things into beautiful language,” she told Rolling Stone last year. “Quite often poems of great beauty are describing something very violent or very ugly. This was really intriguing to me.”

Watch the Official Videos:

At its heart a coming-of-age tale, Orlam (and, by default, I Inside The Old Year Dying) contains the gothic ruralness of Flannery O’Connor, the poetic traditions of William Blake and Robert Louis Stevenson (particularly A Child’s Garden of Verses), as well as the Dorset dialect as meticulously documented by Victorian poet William Barnes (though Harvey remembers hearing scraps of this dialect even during her childhood in the ’70s). “William Barnes had pretty much been at the forefront of collecting the Dorset dialect. He had also created his own dictionary and glossary of it,” Harvey said. “So I used that as my source for all of the dialect and for the glossary in the back [of Orlam].”

Although a straight English translation is included with Orlam, the Dorset version is a charming read, particularly for its expressions like blood beads (berries), engripement (grievance), glory hole (vagina), maggoty (very drunk), piss-a-bed (dandelion), red-bread (vagina, again), skeating (a looseness of the bowels), twanketen (melancholy), and undercreepen (underhanded). Despite its old-timey dialect, Harvey weaves in references to Pink Floyd, The Moody Blues, and, of course, Elvis, making time collapse. “I definitely hoped that I could sort of be in every era and no era all at the same time,” she explains.

Best described as rock-tinged folk, I Inside The Old Year Dying also contains an auditory collapsing of the eras, with Harvey adopting a ’70s Robert Plant wail at certain points, only to replace it with punk-leaning guitar discord at others, and then the singsong of a nursery rhyme punctuated by ambient sounds of children on a playground, or birds chirping, or powerlines thrumming. Like Orlam, I Inside The Old Year Dying is concerned with crafting a world (Harvey refers to it as a “sonic netherworld”), and so it’s not an album that grabs you by the lapels, but one that’s subtle and nuanced and grows all the more enjoyable with each new listen. The experience is enhanced by reading Orlam, but the album also stands sturdily on its own, inviting the listener to soak in its vivid, ghostly atmosphere.

The album starts backwards—eerily, moodily—with the ethereal “Prayer at the Gate,” reverberating at the outset with pulsing beats as Ira-Abel encounters the Christlike Wyman-Elvis on New Year’s Day after a long separation. Those who have grown deeply familiar with Harvey’s timbre over the decades will notice a marked difference, as producers Flood and John Parish encouraged her to try something different vocally. On this particular song, Flood urged Harvey to sing with desperation in her voice, like someone who’s much older and weather-worn.

Harvey and her team made liberal use of field recordings and audio libraries, which is most obvious on the next song, “Autumn Term,” whereby Ira-Abel returns to school after a summer hiatus. Children shout and frolic against a playground backdrop as Harvey now adopts a classic-rock ’70s wail reminiscent of everyone from Zeppelin to the Bee Gees.

The romantic, high-as-the-heavens “Lwonesome Tonight” marches with a galloping folky-ness as Harvey pays soprano tribute to Wyman-Elvis—“Are you Elvis, Are you God? / Jesus sent to win my trust?” And young Ira-Abel approaches the wood with a picnic fit for a King (a.k.a. “The Fat Elvis”): “Peanut-and-banana sandwiches / For this man her shepherd is.”

“Seem An I” starts out acapella, and then somersaults into a slow, swaggering rhythm reminiscent of Rid Of Me’s “Rub ’Till It Bleeds.” But this time, the melody adopts the singsong of both a nursery rhyme and a psychedelic ditty that could have made a cameo in Hair. The song’s title, “Seem An I,” is a bit of leftover Dorset dialect Harvey used to hear in childhood, which translates to “seems to me.” The dialect is particularly heavy in this song overall, which makes it fun to just sit back and marvel at the music of the language itself.

Enjoying this review? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about PJ Harvey:

Spectral and jagged at the edges, “The Nether-edge” references the “chalky” child-ghosts in Gore Wood, as well as Underwhelem folklore about a horseman who was buried upright, still atop his horse, deep in those same woods. Jangly with ambient sampling and scraping discord, the next song, “I Inside The Old Year Dying,” is thunderous and thematic, offering a soaring, bird’s-eye view of Underwhelem while celebrating the village and all of its geographical strangeness.

“All Souls” is a synth-y lament for the heroine’s inability to find Wyman-Elvis, who’s temporarily disappeared. It’s dark and beating with loneliness, like cold raindrops in a heavy storm—“And only by her own gooseflesh / Knows she somewhen he’ll return.” Lead single “A Child’s Question, August” is melodic and meandering, with warm honeyed male-female harmonies and a return to the album’s mantra of “Love me tender / Tender love.”

Meanwhile, the next track “I Inside The Old I Dying” contains unmistakable tinges of “This Mess We’re In,” Harvey’s duet with Thom Yorke on 2000’s Stories From The City, Stories From The Sea. (This time, Harvey recorded her vocals with her eyes closed, again at Flood’s urging, to escape the routine of her voice.) The song again mourns Wyman-Elvis’ absence, as Ira-Abel “slips from her childhood skin” in December in preparation for the new year and a triumphant coming of age, as the chalky children look on.

Going back in time, “August,” confronts the human capacity for cruelty, begging Someone please love me tender, and we become acutely aware of an ache—Ira-Abel’s and possibly even our own—as well as the thin, chalk-scratched line between life and death. Next, the quirky, pounding drumbeats of “A Child’s Question, July” appropriately evokes Björk’s “Human Behaviour,” and the woods come alive with children’s whispers, chirping birds, and sundry forest sounds.

More wooded noises—bees buzzing, sparrows singing—punctuate the beginning of the final song, “A Noiseless Noise,” which ups the ante with hard-hitting drums and buzzing, dissonant, jagged electric guitar. It’s here, in this noisy final plea, that Wyman-Elvis (and, let’s face it, we) are beseeched to “Come away love and leave your wandering.”

Notable Tracks: “A Noiseless Noise” | “Lwonesome Tonight” | “I Inside The Old I Dying” | “A Child’s Question, August”

LISTEN: