Twenty years ago in September of 1998, just a few weeks before I started my senior year at UCLA, I took my first trip to London. It was a revelatory experience for me in many ways. My first time overseas. My first time navigating subway maps and finding my own way around city streets that were completely foreign to me, via the Underground and by foot. My first time trying to decipher the local slang and vernacular (“mind if I nick a fag from you, mate?”). My first time fully embracing the virtues of not being stranded on American soil.

I fell in love with London immediately and unconditionally. But perhaps most illuminating was the heightened musical discovery that welcomed me as I visited the city’s record shops, from the cozy confines of Soho’s beloved (and now sadly defunct) Black Market Records to the chain-store vastness of HMV on Oxford Street. Though I was a relatively broke college student attempting to enjoy my adventures in England as cost-efficiently as possible, I didn’t hesitate for a second in splurging on a few hundred pounds worth of CDs to bring back home to Los Angeles.

One of those purchases was This Is My Truth Tell Me Yours, Manic Street Preachers’ fifth studio album and my long overdue introduction to the brilliance of the musically and lyrically eloquent Welsh trio. My knowledge of the band at the time was confined to the bits and pieces I had periodically stumbled upon in UK mags like Q and Mojo, so I didn’t have too many preconceived expectations for their music. But This Is My Truth did the trick with just one listen, and I was instantly immersed in (and enamored of) their distinctive brand of emotive, cerebral, and politically-charged rock, not to mention their penchant for concocting guitar-driven melodies that stick with you long after the disc stops spinning.

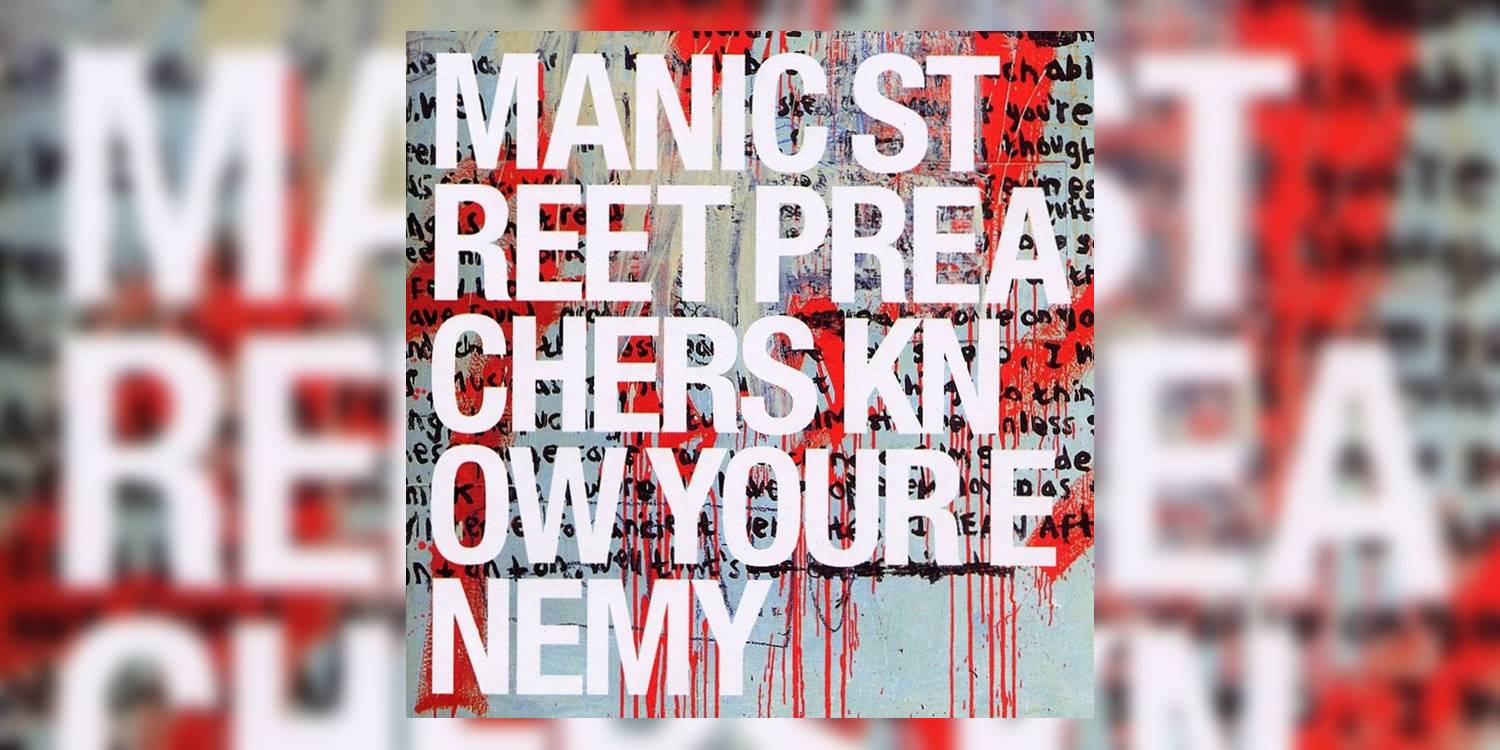

Fast forward roughly two decades and eight Manics’ studio albums later to just a few months ago, when out of the blue, I received an email from one Stephen Lee Naish, who expressed interest in writing for Albumism. In his note, he also mentioned that he had just recently written an entire book about not just the Manic Street Preachers, but about one of their less widely revered albums, an offering that even Manics’ frontman James Dean Bradfield has ranked at the bottom of their discography: 2001’s Know Your Enemy. Stephen’s unorthodox choice to delve deeper into Know Your Enemy, amongst all of the other more prominent records in their repertoire, captured my admiration and curiosity.

Though Riffs & Meaning: Manic Street Preachers and Know Your Enemy has been available in the states for a few months now, this week finds the book receiving the wider international release it most certainly warrants. And I recently had the great pleasure of sitting down with the esteemed author to learn more about what inspired him to write so expansively about the album he refers to as “the eccentric and untameable child of Manic Street Preachers’ records.”

Justin Chadwick: Congratulations on the release of Riffs & Meaning! So your decision to select Know Your Enemy as the focal point of the book is arguably an unexpected one, considering that a handful of the Manics’ other albums are more widely embraced. What prompted your decision?

Stephen Lee Naish: A few reasons, really. Firstly, I didn’t want the book to be unwieldy and expansive. I wanted it to be concise and to the point, so a focus on one particular record was how I approached the project. And choosing that record was quite easy, actually. The records most fans consider as iconoclastic had in some respects already had in-depth analysis in books and documentary films. Know Your Enemy is an example of the Manics’ iconoclast tendencies, but very little has been written about it and its obtuseness has mostly been forgotten or dismissed.

Secondly, it was, at the time of writing, the halfway point in the Manics’ discography. They’d not long released their twelfth record when I started this project in 2014 and Know Your Enemy was their sixth. It was a neat way to pivot back and forth in their career.

And finally, the record was a big one for me, personally. I was at the height of my fandom and expectation for this record was immense. With the knowledge of the band’s past as gobby antagonists, Know Your Enemy felt like an opportunity to recapture that, and as a newer convert of the band I was stoked to have my own extreme version of them.

JC: So when did you first personally discover the Manic Street Preachers and what was it about their music that made you a loyal convert?

SLN: In the early 1990s, I was a metalhead and then a grunger. I was also a reader of the weekly rock press, so the Manics were often in the periphery of those pages. I didn’t give them much thought at the time. My sister had a cassette copy of Gold Against the Soul, which I think I listened to once and put it back in her room. By 1995, I’d embraced indie and Britpop and when the Manics returned in 1996 with the single “A Design for Life” and the album Everything Must Go, I still wasn’t convinced. It took until the last single (“Australia”) from Everything Must Go for me to finally realize they were amazing and exactly the kind of band I needed in order to develop my budding interest in culture and politics.

JC: I’ve always felt that it’s a shame that the Manics don’t have a wider following here in the States. Why do you think they’ve continued to fly just below the radar in the U.S.?

SLN: I agree. But, the fans they have acquired in North America are extremely devoted and have really dug into their history. I’ve never been able to pinpoint why they’ve never broken into the North American market with any gusto.

JC: What, from your perspective, is the greatest song on Know Your Enemy and why?

SLN: That’s a tough call. I remember when I first heard those bursting chords of “Found That Soul” and feeling such utter relief that the band sounded vital and urgent once again. That song is a highlight. But, I’ll have to go with “Intravenous Agnostic.” The same excitement exists as in “Found That Soul,” but it feels more effortless and the lyrics are excellent!

JC: Do you know if the band themselves have read the book? If they were to read it, what do you hope they would think of it?

SLN: My instincts tell me they would never read this book, or read any book or watch any documentary about themselves for that matter. If they did happen to read it, my hope would be that they’d think I’d have done a decent job of praising the record and analyzing the band’s career critically. The best I could hope for would be that they would read it and start revisiting some of these songs live.

JC: If you were to write a second book about a Manics’ album, which album would it be and why?

SLN: Probably Generation Terrorists because there are so many cultural references to follow and so many rabbit holes to fall down. It would have to be very unwieldy and very abstract and completely unreadable.

JC: OK, list-making time. What are your FIVE all-time favorite Manic Street Preachers albums?

SLN: I’ve had the top three locked in for a while now: Generation Terrorists, The Holy Bible, and Know Your Enemy. The last two of the top five switch every few weeks I’m sure, but right now they are This is My Truth Tell Me Yours and Futurology.

Excerpt from Riffs & Meaning: Manic Street Preachers and Know Your Enemy

Manic Street Preachers have always had a tendency to pull focus on one real or fictionalized member of the pop culture fraternity. The earliest example being R.P. McMurphy, the acoustic strumfest and B-side to “Stay Beautiful,” that used the protagonist of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest as a means to protest capitalism and celebrate individuality. When the band released “From Despair To Where” as the first single from Gold Against the Soul they included the hammering hard rock slog of Patrick Bateman — a song that was an original first single contender — as the B-side. Despite the song’s pounding metal backdrop and everything-but-the-kitchen sink approach (seriously, the song contains a sample of the “Star Spangled Banner” and a children’s choir), it perfectly encapsulates the sinister premise and male egoism of Bret Easton Ellis’ 1991 novel, American Psycho.

Everything Must Go had also brought South African photojournalist, Kevin Carter, and abstract expressionist painter Willem de Kooning, into the spotlight. The band pushed the boundaries of who was worthy of cultural revaluation somewhat on Lifeblood with “The Love Of Richard Nixon,” a song that tried to redeem — with lines such as “people forget China” — one of the most crooked American Presidents in history. Nicky Wire, in an interview with Uncut magazine recalled that song’s failure: “I can remember being in James’ flat in Cardiff, hearing Jo Whiley play it on Radio 1. And I knew as soon I heard it… what the fuck have we done?” Thankfully, to even things out, the band included the thoughtful “Emily,” a song that celebrated the life of Emily Pankhurst, one of the leaders of the Suffragette movement.

The lack of euphoric anthems on Know Your Enemy was a striking concern upon first listen. The record’s fifth track “Let Robeson Sing” was the first real opportunity to let Manics fans sing. Whilst a majority of Know Your Enemy has dated over time, “Let Robeson Sing” seems to have only matured, possibly due to the song’s subject matter, which unlike the majority of the record expresses a positive reflection of its politics and its subject.

Paul Robeson was a black American actor, singer, and civil rights activist. He became involved in political activism with the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War (1937–1939), and gave moral support to the leftist Republican troops and the International Brigade fighting against Franco’s Falange. In the era of McCarthyism, paranoia of leftist politics reached fever pitch and Robeson, along with many other artists, writers, actors and singers was blacklisted. Whilst “Let Robeson Sing” might be the life of the album, it could also be an indicator of its death. Released as a single the day before the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, the song’s anti-Americanism was certainly at odds with the defiant spirit the US and its allies around the world were taking as the causes and consequences of the attack unfolded over the days, weeks and months after. For a start the song was critical of the anticommunist McCarthy era, but more importantly the fabric of the American Dream itself (“the lie of the USA”), and US Foreign Policy, which in the subsequent months after the attack was being pumped up with jingoistic flare. It might seem odd that the very Welsh Manic Street Preachers would openly sing about a disgraced commie actor from mid twentieth-century America, but Robeson’s connection to Wales was intriguing. Nicky Wire pointed out that:

There’s quite a big connection. He did a film called Proud Valley which is based on the miners in South Wales, and he was due to come over here to perform at the Welshire Eisteddfod, which is like a celebration of culture and singing and stuff. It was when he had his passport withdrawn by the American government, so he actually sang down a telephone. He sang the Welsh National Anthem down a telephone to the Eisteddfod miners, and I’ve got a CD of this, which is one of the most am amazing, spine-tingling things I’ve ever heard.

“Let Robeson Sing” contains a lyrical premonition, as like Paul Robeson, the band in later months would also go “to Cuba to meet Castro.”

BUY Riffs & Meaning: Manic Street Preachers and Know Your Enemy here: US | UK