I’ve read my fair share of rock bios over the years, so many of which have spun elaborate chronicles of lives lived by music royalty who managed to scratch their way out of obscurity and emerge victorious with their wildest dreams at long last in their grasp. And if they have a few distracted moments when booze, drugs, cars, and a few million bucks happen to complicate things along their journey, far be it from me to protest.

I’m not knocking the genre at all, honestly. Who doesn’t love a good rags-to-riches yarn where the protagonist, in the face of incredible odds, wins out in the end? In many ways, it’s the narrative we want for our musical heroes—and often the one we’ve been sold about a glamorized industry where everything is gold and platinum-plated and talent and persistence always prevail. It’s inspiring, but maybe not terribly accurate.

Fewer volumes have been written about the actual day-to-day existence of working musicians. The ones who are constantly touring small venues—sans entourage with whatever equipment they can lug around in their trunks. The ones who are their own publicists, promoters, merch salespeople, and bookkeepers. The ones who tirelessly write, record, and play in earnest to develop their craft while trying to eke out a living that keeps clothes on their backs and gas in the tank.

In reality, most never catch a break despite doing everything for the right reasons. Where are those stories?

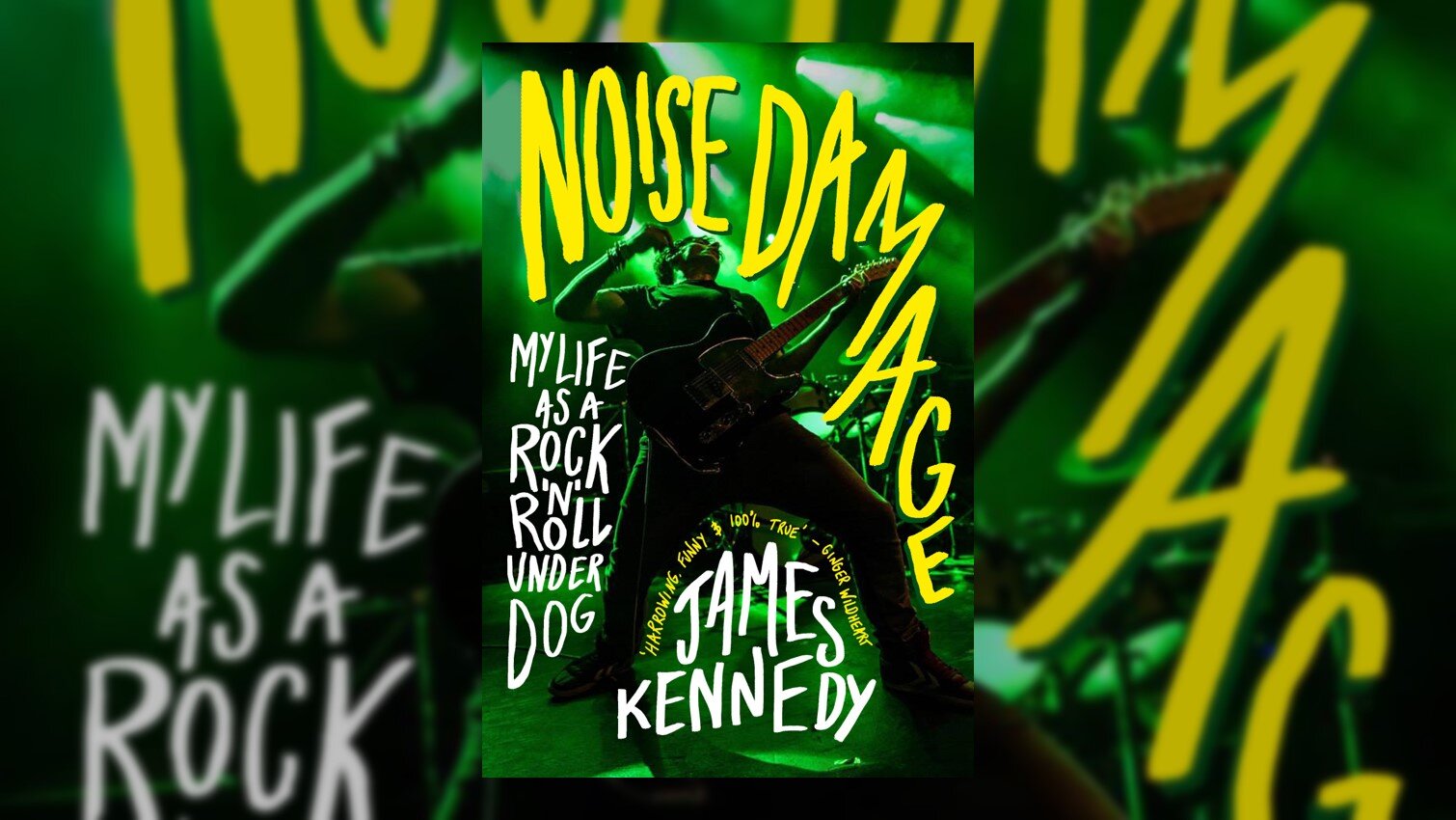

‘Noise Damage: My Life as a Rock ‘n’ Roll Underdog’ is in stores now | Buy

Enter Welsh singer, songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, and producer James Kennedy, whose book Noise Damage: My Life as a Rock ‘n’ Roll Underdog explores the exhilarating highs and crushing lows of music-making. For over a decade, Kennedy fronted the alt-rock outfit Kyshera —a band that, all things considered, should have become worldbeaters. Despite being courted by major labels, receiving accolades from across the industry, and establishing an enthusiastic following wherever they took the stage, the trio’s prospects were swallowed by the massive industry sea change of the aughts/noughties. While perpetually skirting the precipice of commercial success, the band crumbled under the weight of it all. By 2018, Kennedy was the sole remaining member.

Kennedy writes Noise Damage with toothsome detail, unfolding a cascade of anecdotes of sleepless nights in rental vans, water bottle showers, and mutinous managers. At the center of his reflections are the complex relationships between him and his bandmates, revealing how intricately entangled their personal and professional lives became both their strength and their proverbial albatross. Kennedy puts himself on blast, too, accounting for his own internal struggles and flaws that undoubtedly figured into the equation.

But, Noise Damage isn’t overtly bitter and resentful. Kennedy is just as quick to point out that the years he spent with Kyshera were at many points blissful and life-giving. It’s as much a love note to music as it is a cautionary tale about its pitfalls.

While Kyshera didn’t survive the storm, Kennedy is thriving as a solo artist. His latest album, Make Anger Great Again, which arrived this past September via his independent label Konic Records, is a fitting companion piece to the book. Made entirely in his home studio, the set is loud and politically charged, and unquestionably reactive to the dizzying world events of the past year. But, it’s also a testament to Kennedy’s consummate musicianship—he wrote, played, sang, and produced every single note.

Kennedy and I sat down earlier this spring, spending an hour-and-a-half bantering about our favorite musicians, our families, and the trials and tribulations of working for a living during a pandemic. Eventually, we got around to discussing Noise Damage.

I want to tell you how much I loved reading Noise Damage. I imagine it was cathartic for you to write it.

Yeah, it totally was. I think that’s kind of why I wrote it. I wrote the whole thing very fast—in two months, start-to-finish, done. I hadn’t intended on ever writing a book. I’m a massive book fan and a massive reader. But I never had any ambition to write, never thought I could write. The first day I came in and sat down and actually started the intro, I cannot for the life of me remember what motivated me to do that. I just came in and I started doing it.

The whole reason for me doing it, if I look back, was catharsis. My band Kyshera broke up in December 2018, middle of the month, and two weeks later I started writing Noise Damage. I think what happened was the thing I’d committed my life to for the past ten years—the band —had suddenly, officially ended, and I think I was at a point in my life age-wise, and in general, where I was reflecting on ‘okay...what does this mean now? What am I without this? What do I do? Who am I?’ So, I think I was going through kind of an existential crisis that had been thrust upon me by the band members leaving. I just started reflecting, really.

As I got about halfway through, that’s when I started to realize ‘this feels like a book. I’ve got a lot to say here. I’ve got a lot of stories and insights. I’ve actually done way more than I thought I’d done.’ That’s when it started to take shape. Every day, I’d come in at about 6AM and for ten hours just hammered it out.

Once you had figured out that this was potentially going to be a published work, did the process become any more difficult?

It wasn’t so hard for me because I was writing about myself, and what came out of me was my story. At the time that I was writing it, I didn’t have a publishing deal. I didn’t really think that anyone was ever going to read it. And I think all of that helped, because now the book’s done well and I’ve got three literary agents offering to represent me.

The next book I write, I think, will be very different because there’s sort of an expectation and precedent set there now. When I wrote this one, I honestly just wrote it for myself, and I thought maybe some of my musician friends might find it funny. There was no expectation above that.

The idea that it would be on the shelves of my local bookstore was not even [laughs]...fathomable. So, it was quite easy. I wrote about my life story for my own fun.

Have you gotten a lot of positive response from fellow musicians who have likely seen a lot of themselves in your story?

So much of it, yeah—from my friends and my peers. The response to the book has been amazing. I don’t know about the States—that’s a much bigger landmass and I haven’t really had any promo over there to speak of. But in the UK, it’s done incredibly well—because there’s the eBook as well, and I think people have been sharing that and it’s kind of doing the rounds now.

I’ve had people message me constantly, and I’m finding things in my spam folder on Instagram —people with long messages saying, ‘I had the exact same experience, and I’m so glad you’ve spoken out about having bad hearing and bad mental health. Thank you for writing this book.’ I keep saying to people, ‘can you please leave me a review? Because the amount of messages I get are about ten times the number of reviews I’ve gotten [laughs]. It’s, like, ‘come on guys, don’t tell me, tell Amazon!’

I'm not necessarily surprised given the conversations I've had with many artists, but I think some music fans might find it difficult to comprehend that a talented, well-liked band leader could suffer from low self-esteem, which is something you discuss from your own experience in the book.

Yeah, yeah, I think people think that the person [they see] on stage or on camera is the person. So many of my friends who I know so well are very different on stage. Some of them front heavy thrash bands and are absolute monsters on stage—intimidating guys. But, I know them as being these delicate little flowers who are shy and fragile [laughs]. And I’m very much the same—on stage, a different guy comes out. And it’s not an act or anything—it’s a part of me, but it comes out [there], and then I go back to being a quiet, sort of introverted person, you know?

I find that a lot with entertainers, comedians, and artists in general. For me, that’s very normal, but I know for the public it can be a shock when they meet their idols, they’re actually quite meek [laughs]. The bigger concern for me is when you meet people and they’re exactly the same as they are on stage. That’s slightly more worrying, really—these guys who are arrogant like Gene Simmons. It’s, like, ‘come on, man! You’re just playing guitar in a band. You’re not saving lives. Bring yourself down to earth a little bit.’ You know?

You and your band mates played on countless stages, so I imagine those gigs must blur together at some point. Were there one or two shows over the years you remember as being particularly great?

Yeah, it was always the smaller ones—it was always the ones in our hometown, or in London. We’ve always had a lot of love in London even though we were from South Wales, about three hours away. London was always very good to us. It was probably the launch parties for our first independent album, Paradigm, in 2010. We played a gig in Cardiff, and then a launch party in London—both of those stand out, even ten years later, as my favorite gigs. It was all friends and family, you know? We were playing new songs with a new lineup, and the band had this kind of fresh energy. We were just starting out on this kind of second wave of the band. All of our friends were there and we were enjoying the new songs, and we sounded great. They were small clubs, but they still stand out to me as the moments when we were, like, ‘yeah! I’ve just had a lot of fun tonight.’ You know what I mean?

The bigger gigs we’ve done on the beach in Italy and stuff, which were awesome—outdoor gigs and you have the Italian Sea there—I wanted to kill everybody. We’d had so much crap on that tour with our management messing us around, which you would’ve read about in the book. To the audience it looked like ‘man, these guys are living the dream!’—and I should’ve enjoyed the moment more. But the other stuff just kind of took over, I think. So, my favorite gigs were all the small ones where everything felt like it was as it should be.

Those tensions that surrounded you—did they ultimately push you and the band to make better music and play stronger on stage?

I think it probably did. We had a lot of tension within the band, as well—a lot of lineup changes. Two of the drummers used to cause a lot of drama before gigs...it’s always the drummers for some reason [laughs]. But they were both great musicians, and on stage we really had it together. But the tension and friction beforehand often created a kind of winning energy on stage.

Man, and the injuries we had—there was once when I actually fell through a stage. We played a gig in a pub in Birmingham where Black Sabbath used to play when they were starting out—everybody’s played in this place and it’s really a piece of local music folklore and history. The same stage is still standing there. We didn’t last one song before I fell through the stage. There was the massive hole, and I’d ripped up my leg and everything—and it was because I was so angry because the drummer had been winding me up before we’d started. I hadn’t even sung the first line and we were jumping around releasing all this pent-up anger and aggression. So, we destroyed the stage that had survived Black Sabbath [laughs].

I loved that story in the book. And the fact that you just continued to play as if it never happened. The club's management sort of looked the other way, too, right?

[laughs] Yeah, yeah. All I was thinking was, ‘oh my God...I cannot afford to pay for this damage.’ The ironic thing is that they were thinking the exact same thing about us, like, ‘man, this is a health and safety disaster. We probably should’ve sorted that years ago, and now he’s gonna sue us!’

Who was the first artist you heard as a kid toward whom you remember gravitating in some significant way?

My parents have told me that I’ve always been into music. You know, as a child of the ‘80s, it was obviously Michael Jackson. I was a massive fan. I remember learning all of the dance moves, as every kid my age probably did, you know? I had all of the songs down and I performed them for my family, and things like that. Prior to that, I can’t remember much. That was sort of my childhood musical memory, just being obsessed with him. But I think that was pretty normal for kids who were my age at the time.

I think he roped in every kid of our generation. I think I was about six when Thriller was released, and I don't think I knew anyone who didn't have a copy in their house. I was the oddball who liked "Human Nature" more than "Billie Jean" or "Beat It.”

They’re all good, man! I was from the Bad generation, so Thriller for me was something I’d kind of discovered later. When I was growing up, all of the singles from Bad were on the radio—and almost every song from that album was a single. So, I didn’t have an actual copy of the album, but I had this little tape recorder which could record from the radio, so I recorded all of his songs that played and made my own album out of it. Yeah, I remember doing that and just obsessing over them, learning all of the little vocal quirks and things that he did.

But I never had any sort of ambition to be a musician. Whatever I’d be into, I’d be really into it, you know? So, I was really into pop music and stuff as a kid. Then, I got into comics and drawing my own comics, and then I was really into LEGO and building my own toys. I was always into very solitary creative things, and I’d get obsessed with them.

Then my dad bought me a guitar, and I was obsessed with that. He showed me how to play one little blues lick, and I picked it up right away. A little switch just went off inside me. As I said, I had no ambition to be a musician before that—or to do anything music-related, for that matter. But as soon as I could play that one riff, something switched in me that I didn’t know was there. For the next five years, nobody saw me again—I was just in my room with this little Spanish guitar [laughs] just playing the blues.

I've probably tried to pick up the guitar at least a dozen times over the years, and I've found it really hard to stick to it. I get so frustrated when I don't get something the first time, so I think I'm going to need lessons to help me make some progress.

Oh yeah—I’d definitely recommend it, man. I’m exactly the same way as you. Luckily with the guitar I picked it up straight away and I had a natural sort of talent for it. There’s a lot I still want to learn, and there just aren’t enough hours in the day for me.

Knowing everything you do about the industry now, what do you tell artists who come to you for advice on how to navigate it?

Well, I think things are very different now. There’s an established model for everything now. I mean, there was one back in the day when we got started, but then it changed and, for much of the time when we were around, it was a no-man’s land where the old industry had died and the new one hadn’t really happened yet.

The advice I’d give people now is that it’s better now, and there are more opportunities now. Back in the day—in the bad old days—if you couldn’t get a record deal, you know, it was over. You couldn’t go and make an album in the studio because it would cost you...you just couldn’t do it. It would be impossible. And even if you did, what were you going to do with it? You’d have a massive reel of tape, and...so what?

At least these days you can make a record in your home for free, or for very cheap, and you can put it on the internet and promote it on social media. It’s not the end of the world now...it’s not the kiss of death if you can’t get a record deal. There are other options, you know? I always say to people that the best thing is to do everything yourself for as long as you can. Don’t rely on anybody—you don’t need to anymore. Make your own records, make good music, get it out there, promote yourself, play live, get good, and keep doing it for the right reasons. The opportunities will come to you.

So let me pause for a second and talk about Make Anger Great Again. You assembled that entire project, start-to-finish, in your home studio.

In this room, yeah!

It's a credit to your abilities, because it sounds like a record that was orchestrated by many hands. Is this the way you think you'll make music from now on?

Yeah, I wrote the whole album and recorded it in three months, in this very chair, in this room, in my house. It was great. I played all the instruments, so I had no bullshit to deal with in terms of musicians, labels, management, or deadlines. I just made the record I wanted to make on my own terms and on my own time, and put it out. Which is so empowering and so cool to be able to do that.

I’d kind of been doing that all along, though. This is my seventh album—I’d done three with Kyshera and four solo albums, and they’ve all been really different. My first solo album was really experimental electronic music, and then I did a very simple acoustic folk kind of album, followed by a more middle-of-the-road soft rock record.

I’m so used to now just doing whatever the hell I want, when I want, that I think if I got a record deal now and they started giving me deadlines and saying, ‘I don’t like this song, don’t like that song,’ I think I would find it very difficult to operate in that kind of arena now. I’m so used to just doing my own thing.

Trying not to ask the clichéd “what's next” question, but what kind of record would you like to try and make after this one?

I never know until it comes. This record, I had no idea about what it would be until it happened. All of them are just so different because I get really into the thing for a few months, and I write the whole thing and record it all, and then I feel like I’ve gotten it out of my system. I don’t know what the next thing is going to be until it comes.

There’s very little consistency with my musical output. Even within Kyshera, you know, we did seventeen different styles within one song, you know? [laughs] The only consistency with me, I think, is the versatility and the eclecticism—the inconsistency is the consistency. I’ve just done the album, and it’s been out for seven months now - and the book’s been out for six—so I’m very much still caught up in that cycle at the moment.

I really don’t know. It might be a blues record, or it might be an experimental jazz record. That’s the beauty of the freedom I’ve now been able to build for myself is that I’ve got my own label and my own studio, and I can play all the instruments and produce my own records. That’s the awesome thing that comes with it. Now, I haven’t sold a gazillion records and I haven’t got any gold discs on my wall, but I don’t have a day job and I can put out the music I want and I’m not answering to anybody. I’m paying my bills and haven’t had a day job since I was twenty-five or something, you know?

So, I think there are options for young artists coming up. You might not become the next Aerosmith or Bring Me The Horizon or anything like that, but you can still make a good living.

I've had mixed feelings about what the industry looks like now, I guess, but I do kind of like the fact that the playing field has been evened in some ways—that if you make good music, you have a realistic chance of being heard by an audience.

Yeah, and we’ve got different problems now, I think. I mean...how do you get heard on that big playing field is the thing now, right? Everyone’s putting out content now, so how do you get noticed above all the noise? And how much do you have to do to make a living now and put food on your table? These are new questions we’re having to answer now. But I think the benefits of the new model now outweigh the benefits of the old one, for sure.

So, in this new iteration of the industry when you're creating everything on your own, what do your non-negotiables now look like when you eventually need to partner and make connections to get your music out into the world?

Uhh...I think I’m pretty good. I can compromise. Maybe the things that are deal-breakers for me would have to do with the music and the lyrics. I only produce my own records, you know, because I can. I would much rather somebody else did it—I don’t enjoy doing it, and I don’t know if I’m particularly good at it, but I am able to knock a record out. So, I do it because I can and I’ve got a studio in my house.

But I’d much rather go to a studio and have someone else do it and do it better. I could compromise on that. I think if I’ve put my heart and soul into a piece of music and I wrote lyrics that I thought were authentic to how I feel, and somebody said to me ‘I don’t think you should say that, I think it’s a bit risqué,’ or ‘I don’t think you should put that chorus there, I don’t like it,’ I think that would be challenging something that is quite a fundamental part of what I do as an artist. There would be friction there.

If you could bring anyone in the booth with you to produce your next record, who would you want?

Oh, wow. Well, Steve Albini. Everybody loves Steve Albini. He would be one, for sure. That sound, man. People talk about the ‘Steve Albini sound,’ and I know he hates that because he’s got lots of sounds, you know? He’s definitely got a stamp, for sure, that he puts on his records, and he’s got an interesting way of working, as well, that I think would be fun. Andy Wallace, as well—I know he’s predominantly a mixer and engineer, but what he did on Grace, Jeff Buckley’s album, with the production and the engineering was just up there as a timeless masterpiece. Flawless. So, they’d be two guys at the top of my list.

Outstanding. I think I surprise some artists when I ask about producers and the relationships forged in the studio, but their impact on the finished product can be significant.

Some guys have just got it, man. It’s just like playing the guitar, you know? I can play a Jimi Hendrix song note-for-note and it doesn’t sound like Jimi Hendrix. And I think it’s the same with producers. I’m self-taught in everything, including production, and every album I do, I learn a little bit more from the mistakes I made on the record before. So, I’m always watching tutorials and trying to figure out ways to get around problems.

And then you see these asshole producers who are like ‘yeah, you just press this button and nudge that EQ!’ Then I’ll do the exact same thing and it doesn’t sound anything like it [laughs]. Some of them have just kind of got that magic touch, you know?

What do you aspire to be better at musically?

That’s a great question—I’ve never been asked that before. Uhh...I don’t really know...no? You know, I consider myself to be a jack of all trades and not a master of anything. I would like to be better at everything I do. I’d like to be a better lead guitar player, a better singer and vocalist, a better arranger and producer. I’m constantly honing my skills across the board. If I could be random and just pluck something out of the air that I’d love to do—I’d love to be able to play a guitar solo like Allan Holdsworth.

Knowing your love of the stage, you must be itching to get back out on the road with this record. Hopefully soon?

I had a chat with a booking agent yesterday, and he thinks that national touring is probably going to be a thing towards the end of this year—but it’s going to be small venues because of the quarantines and keeping the numbers down. All of the big summer festivals here have pretty much been cancelled now—Glastonbury and all of that—and international touring for big bands is probably not going to happen.

Domestic, small-level tours could probably be happening by the end of the year, though—certainly live music in bars will, I think. For me, yeah, I was hoping to do a tour in the UK—maybe nip over to Europe and do some dates there. But if that’s going to happen, it’s going to be 2022, I think now.

Which is a shame because my record is going to be over a year old at that point, and it’s a really aggressive, loud, pumping record that I can’t wait to play with a band, you know? It’s going to be fuckin’ awesome. People are just going to have to accept that if I’m playing songs from an album that came out in 2020...they’ll just have to roll with it [laughs].

Something tells me they'll be just fine with that. I honestly think people will be so overjoyed to hear live music regularly again they're not going to discriminate. I really miss it, myself.

Yeah, I miss that—and I miss playing live, obviously, and I’m excited to get out and do that again. Apart from that, other than being able to see my parents and give my Mum a hug—you know, those small kinds of normalities—I’m getting loads done. No distractions, no social obligations, nobody turning up at my door. It’s awesome [laughs].

Right. The pandemic has been good for creative types in at least a few ways. So, how does that bode for the future, from your perspective?

I think things like this will stay—you know, like live-streaming concerts and Zoom interviews. I can definitely see that being a thing. That’s something good that’s coming out of this. I’ve been doing a lot more interviews lately, which would have been harder to orchestrate. And also, if I’m trying to reach out to people in the industry, everyone’s home. Usually, if I try and contact the book publisher or an agent, they’re either in a meeting, or they’re at lunch, or they’re out, or some other bullshit. Now everyone’s home, so I’m just getting so much done, you know?

But of course, playing a gig online will never replace a live show. Nothing will ever replace that. I’ve had a lot of conversations with friends and have been asked in interviews about the state of the live scene after this, and I’m really optimistic. I don’t think there’s a great immediate future ahead of us. Small venues are closing down left, right, and center in the UK—they were struggling anyway, but COVID just basically put the nail in the coffin. A lot of stuff is going to change, and a lot of venues have been going, and will go, which is obviously really sad.

I think there will be one or two years after this where the dust is settling and things are kind of finding their feet again, but I know that live music, no matter in what capacity, is not going anywhere. There’s just no substitute for it and it’s irreplaceable. Even if all the venues close down, you’ll see it popping up somewhere else. You’ll see people doing gigs in other people’s houses or in garages, or run-down warehouses. It’ll come up somewhere else.

There are industrial problems, which is a real shame. You’re seeing some of these great, iconic venues—ones that I love—close down recently. It’s so sad. These places I’ve played so many times and had so many great memories in, on stages that have been shared by Jeff Buckley, and Rage Against the Machine, and Muse, and Coldplay, and all these iconic bands who grew up playing these small venues—they’re gone now. And that’s such a travesty, not just for the music, but also the history. But something else will take their place.

In the spirit of our site, what are your top five albums?

Wow. Okay, yeah, I think about this all the time. Top five is a difficult one, but I kind of know straight away which ones would be in there. These aren’t in order, but Jeff Buckley’s Grace is always in there. Frank Zappa’s We’re Only In It For the Money—that would be in there.

Mmm...Radiohead’s OK Computer, and Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon—I guess everyone would say that. Shit. I’ve got one more.

This is quite tough! I was confident going in—I was, like, ‘yeah, I got this covered!’ Now that I’m thinking about it...hmm. If I had prior notice, I would have had a killer list. I need one more...shit. What’s the last one gonna be? It’s a funny thing when you’re put on the spot—your brain goes blank, doesn’t it? Okay...Smashing Pumpkins’ Siamese Dream.

Note: As an Amazon affiliate partner, Albumism may earn commissions from purchases of vinyl records, CDs and digital music featured on our site.

LISTEN: