Happy 45th Anniversary to The Jacksons’ eleventh studio album ‘The Jacksons,’ originally released November 5, 1976.

During the early half of their tenure on Motown (1969-1971), the Jackson 5—Michael, Jermaine, Jackie, Tito, and Marlon—rose to become one of the label’s biggest stars. It was during this productive period that the brothers amassed an unprecedented string of four number-one hit singles on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart in addition to scoring mega successful albums, including their 1969 debut long-player, Diana Ross Presents the Jackson 5, their grand 1970 trifecta—ABC, Third Album, and The Jackson 5 Christmas Album, and 1971’s Maybe Tomorrow and the soundtrack to the Goin’ Back To Indiana TV Special.

While Motown’s golden “Sound of Young America” age began to wither right at the turbulent tail end of the Sixties, the Jackson brothers’ ascension proved the perfect antithesis to the label’s crossover aspirations of the Sixties and its transitional, and at times complicated, era in the Seventies. Youth may have gravitated toward several of Motown’s biggest acts before, but the Jackson 5 themselves were teenage idols and their appeal was squarely aimed at, as their 1970 cover of the Diana Ross & the Supremes gem suggested, the hip, colorful, and happening “Young Folks.” The age of ‘Jacksonmania’ was in full swing and everyone felt it.

Their fanatical fan base of preteens and teenage girls saw them as the ultimate heartthrob sensations, singing their praises, flocking to their sold-out shows in frenzy, and hanging memorabilia on their bedroom walls. With their wildly diverse musical settings, cutting-edge performances, and effervescent energy, the Jackson 5 were the embodiment of the young, gifted, and Black generation that defined the early Seventies.

Even though they were very much a breakout crossover act, the group never compromised their image or identity to appeal across demographic markets and cultural lines. Not to mention, the group’s youngest member and front man, Michael Jackson, was a gifted entertainer with killer charisma that won over millions around the world. Long before he was crowned as one of pop’s defining figures of the 20th century, he was pop’s definitive child star. In combining their blend of sunny side-up, bubblegum pop with doses of psychedelic soul and funk, the five Gary, Indiana natives became a permanent fixture not only in Black popular music, but the American pop fabric.

However, by the middle of 1972, things began to change.

The pop music landscape was adapting to an underground musical and cultural craze that hadn’t quite exploded in the realms of mainstream America yet. As the wide-ranging sounds of early disco music emerged from several of New York’s booming Black and Gay nightclubs, producers and musicians understood its alluring impact and strived to implement its euphoric elements in their own music.

Meanwhile, an already established sound that originated from the city of Brotherly Love was gaining widespread attention and making the rounds across the music landscape. With its sweeping, lush symphonic arrangements, driving funk-induced grooves, and unshakable jazz overtones, Philadelphia soul was now seen as the domineering stylistic progression in the R&B and disco realm. Even as its producer-songwriter oriented approach was lifted directly from Motown’s hit-making machine of the Sixties, its smooth melodic style and wide-ranging topical range was in a class of its own.

Given that the Jackson 5 had become a major pop entity by that time, Motown saw the potential of furthering the group’s commercial success and appeal by launching solo careers for Michael, Jermaine, and Jackie. While Michael and Jermaine found incredible success with their respective solo endeavors, the Jackson collective’s popularity and impact began to be tested.

While their viability as public figures and performers was still high, their record sales took a dip. A primary factor was that the group was maturing beyond the bubblegum pop-soul aesthetic that informed much of their earlier work. Michael, in particular, was experiencing puberty challenges, causing his once-brightly toned soprano to develop into a fuller tenor. Motown was facing problems in finding the group material that could fit their maturing style, and certainly the brothers were less than thrilled about the label contributing to their stagnant direction.

It is also notable to mention that the bubblegum pop invasion was becoming incredibly stifling for the brothers, in that they were immediately being pent-up in the media as competing rivals with other family groups, such as the Osmonds. In 1972, the group of songwriters and producers that were responsible for much of the Jackson 5’s work, the Corporation, had disbanded, leaving the brothers to seek out an entirely refined musical approach.

Coming off an awkward period of artistic transition with 1972’s Looking Through the Windows and early 1973’s Skywriter, the Jackson 5 unveiled their three final long-players for Motown—1973’s G.I.T.: Get It Together, 1974’s Dancing Machine, and 1975’s Moving Violation—pursuing adventurous and harder disco-funk territory. The brothers scored their last big smash with Motown, hitting the top of the charts with the massively influential “Dancing Machine” single in the summer of 1974. Frustrated with the lack of artistic freedom and financial support his sons were receiving from Motown, the brothers’ patriarch and manager, Joseph Jackson, began shopping around for a new label. Joseph struck gold when he negotiated a deal with CBS Records that represented ten times the royalty rate of the brothers’ previous contract at Motown.

On June 30, 1975, the Jackson clan (sans Jermaine) announced during a press conference that they were leaving Motown Records to start anew on CBS Records as ‘The Jacksons’ (the band’s moniker ‘the Jackson 5’ was owned by Motown). Spectators and their fan base alike were left bewildered by the decision of the brothers ending their seven-year association with Motown on bitter terms. Not to mention, brother Jermaine chose not to follow them, as he was married to Berry Gordy’s daughter Hazel and was determined to stay at Motown to further his solo career. Their youngest brother, Randy, would take his place.

There was indeed stormy weather in Jacksonland, but greener pastures were on the horizon.

Jackson biographers and music historians alike have written off their early post-“Dancing Machine” period, where the Jacksons left Motown and signed to CBS, as troublesome years for the collective solely because their commercial grip on the pop stratosphere they once dominated was slipping. However, this perspective is largely misguided. The obvious point that is constantly overlooked is the unique artistic framework of this grossly underrated period and how it impacted their subsequent endeavors.

The Jacksons had strong ties with Philly soul right from the very beginning. Known for their affinity for covering pop classics of the day as well as adapting to the respective musical climate, the brothers covered Philadelphia soul staples like “La La La (Means I Love You),” “Ready or Not (Here I Come),” and “People Make the World Go ‘Round.” In 1973, Jackie cut his eponymous solo debut for Motown, Jackie Jackson, which had subtle Philly overtones in its musical approach and found him covering the Delfonics’ “Didn’t I Blow Your Mind (This Time).”

Several of the group’s original songs, such as “It’s Too Late to Change the Time,” “Don’t Say Goodbye Again,” and “To Know” had signature stylistic and thematic pulses that derived from Philly soul. The brothers’ final album on Motown, 1975’s Moving Violation, features edgier dance and funk elements that were based in the Philly soul tradition. In fact, if one listens closely to 1975’s Moving Violation, one can argue that the nine-song gem set the precedent for what was to come when they entered Sigma Sound Studios in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, during June 1976, to work on their Epic and Philadelphia International Records (PIR) debut release, simply titled, The Jacksons.

They were smartly paired with Philadelphia soul mavericks Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff, MFSB, McFadden & Whitehead, and Dexter Wansel in 1976, at a time when Philly soul’s imprint on the music landscape was ubiquitous. The songwriting and production duo Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff, in particular, already enjoyed huge success with acts like Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes, The O’Jays, Billy Paul, Lou Rawls, and the aforementioned MFSB. Their collaboration with the brothers may have proved to be a daunting task, but it was far from a fluke.

With the Jacksons’ musical charm and Gamble and Huff’s masterful direction, it was a match made in heaven. If their Motown swansong Moving Violation functioned as a grand nod to the proto-disco-funk craze that Philly soul ignited, then The Jacksons solidified their glorious excursion into the Philly soul stratosphere as sophisticated, adult R&B stylists, setting off the second golden phase of their artistic rise. The professionalism and precision that the brothers worked hard to establish during their tenure at Motown were well embellished on this album.

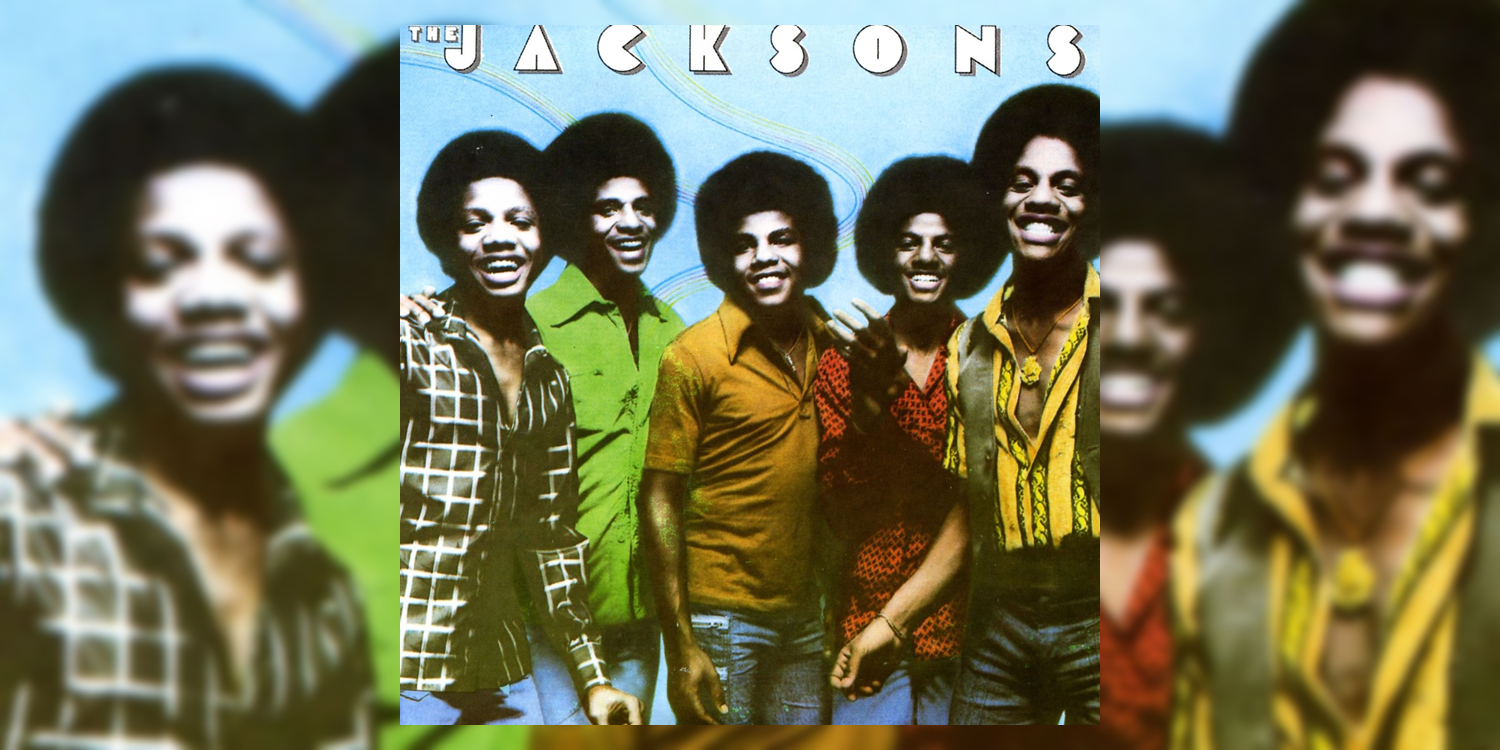

Even before you lend your ears to the sweet and soulful sounds of this ten-song juggernaut, you can’t help but be swept up in the lighthearted, nostalgic fun of the album’s artwork, in which revered photographer and filmmaker Norman Seeff shot portraits of the group. On the front cover, the five Jackson men stand tall and proud, smiling cheek to cheek, with an aqua-colored background behind them. Their perfectly round afros and casual attire shine with a warm, mid-Seventies glow. In the portraits, you can feel the true ‘brotherly love’ that the Jacksons had for one another.

There is a breathtaking serenity and beauty to the back cover and inner black-and-white portraits, which capture their maturity and resilience as a family group. They couldn’t have complemented another album as exquisitely as this one. In listening to all ten of the album’s compositions, you are instantly transported to a sunny era in the mid-Seventies when positivity and love filled the air. As chaotic as the times were, music moved feet and put minds at ease. The Jacksons’ earlier music greatly informed the innocence and naivety of the “Young Folks” that had been born out of the commitments of the Sixties’ promise, but their new sound reflected the strains and ambitions of the “Young Folks,” right at the brink of mid-Seventies hedonism.

The album opens with the bouncy, mid-tempo stepper “Enjoy Yourself,” where Michael showcases his delicate tenor under the Vaudevillian-like, pulsating funk groove. Jackie manages to have a co-lead part during the song as well. The song is written from the standpoint of a young man, convincing an uptight girl at a party to leave her worries behind and soak up the carefree pursuits of life. It was the album’s lead single, peaking at #6 on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart and #2 on its Hot Soul Singles chart. The song is also notable for becoming the Jacksons’ first single to be certified Platinum by the RIAA and also being the first to feature their youngest brother, Randy.

Continuing the festive affirmations of positivity and independence captured on “Enjoy Yourself,” the energetic “Think Happy” has a rocking, gospel-influenced soul rhythm that is reminiscent of the groove utilized on the O’Jays’ 1973 hit “Put Your Hands Together.” Throughout the song, Michael showcases a rather early example of his energetic call-and-shout technique that would become one of the defining mainstays of his vocal approach.

The album moves into moodier territory with “Good Times,” a majestic soul ballad that finds Michael and his brothers delivering some of their most passionate vocal work on record. Anchored by MFSB’s subtle musicianship that defined Gamble & Huff’s great ballad work, the song focuses on a man reflecting on the wonderment of his lover and the love they once had. Even though it was never a single, the song became one of the Jacksons’ most enchanting numbers and a popular staple on regular quiet storm airplay, even today.

Influenced by fellow Philadelphia International powerhouses the O’Jays, “Keep on Dancin’” manages to pull a two-dimensional groove of deep funk that features some amazing Moog bass synthesizer work, courtesy of Dexter Wansel, with Michael floating on the groove with some of the most Stevie Wonder-laden inflections in his vocal approach. The song then transitions into disco territory, which is strongly reminiscent of the O’Jays’ 1975 hit “Livin’ for the Weekend.”

The slinky “Blues Away” showcases one of the prominent hallmarks of Michael Jackson’s stunning artistry, as he used his life as inspiration to fuel his art. Credited to Michael as its sole writer, “Blues Away” centers in on a young man succumbing to the deepest ebb of his depression, feeling unable to fully cope with it. It was the first song ever published in the Jacksons’ repertoire, where one of its members wrote it—a token of freedom they were never given at Motown. The song’s seductive, jazz-soul backdrop contrasts with the seemingly dark nature of its empathic lyricism, giving the song an overall melancholic quality. The song also staged early examples of Michael’s percussive vocal approach, where the dramatic hiccups and beatboxing would soon become distinctive mainstays. It is the absolute precursor to many of the themes of loneliness and desperation that would be revealed on the Jacksons’ 1978 coming-of-age masterpiece Destiny, which functioned as an emotionally impacted testimonial, chronicling the joys, anxieties, and contradictions of Michael’s own journey toward personal fulfillment.

The second half of The Jacksons is a shining emblem of Gamble & Huff’s commitment to bringing “a message to the music.” Known for effectively using their social insight to reflect the weary times, Gamble & Huff gave the Jacksons a refreshed edge to emote their concerns for humanity and the social apparatuses of the day. The album’s second single “Show You the Way to Go” is often mistaken by some to be a romantic song, when in actuality, it is an inspiring call for unity in the Black community. Michael’s maturing tenor twists and turns around the ballad’s delicate, quiet storm groove, with a tender, double-tracked chorus to boot.

“Living Together” and the McFadden & Whitehead-penned “Strength of One Man” further the sentiments of brotherhood, peace, and harmony that Philadelphia International’s message-oriented work was known for and suited the brothers’ deepening vocal styles thoroughly. The album’s final two songs, the ethereal“Dreamer” and the Michael and Tito-penned “Style of Life,” pick up the themes of introspection and broken romance that were found on the album’s first half.

Released in the fall of 1976, The Jacksons proved to be a rebound for the reinvigorated group. The album missed the top 20 on Billboard’s Pop Albums chart, peaking at a modest #36 and staying on the chart for twenty-seven weeks. On Billboard’s Top Soul Albums chart, it reached #6, similarly to their previous release, Moving Violation. The album would be certified gold by the RIAA in April 1977.

The brothers’ commercial clout on the pop shores may not have been as earth-shattering as it was during the glorious rise of their early Motown tenure, but their music and public presence were still welcoming. Certainly, their urban loyalists greeted their Philly soul knockout with glowing enthusiasm, as they always had. To promote the album, the Jacksons made several television appearances on “The Freddie Prinze Show,” “The Sonny and Cher Show,” and “The Mike Douglas Show.” Given the album’s success, Gamble & Huff cut one more album with the group on their Philadelphia International imprint with 1977’s Goin’ Places, another underrated slice of Philly soul, albeit one that explored more adventurous territory and failed to attract the same commercial rewards as their Epic debut.

The Jacksons was, in more ways than one, an exhilarating labor of love for both the Philadelphia International collective and the brothers from Gary, Indiana. There were those who were uncertain if the brothers could actually stand up to the timeless quality of the Philly soul tradition, and they fit right in. While the album’s masterful blend of disco and Black pop may not have broken new stylistic territory for Gamble & Huff, it certainly did for the Jackson brothers, re-positioning them right in the center of R&B’s golden brass. They may have hit higher artistic and commercial plateaus on their subsequent releases, but this was an important leap in their artistic prowess. Forty-five years later, it’s still making the world ‘think happy.’

LISTEN via Apple Music | Spotify | YouTube:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2016 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.