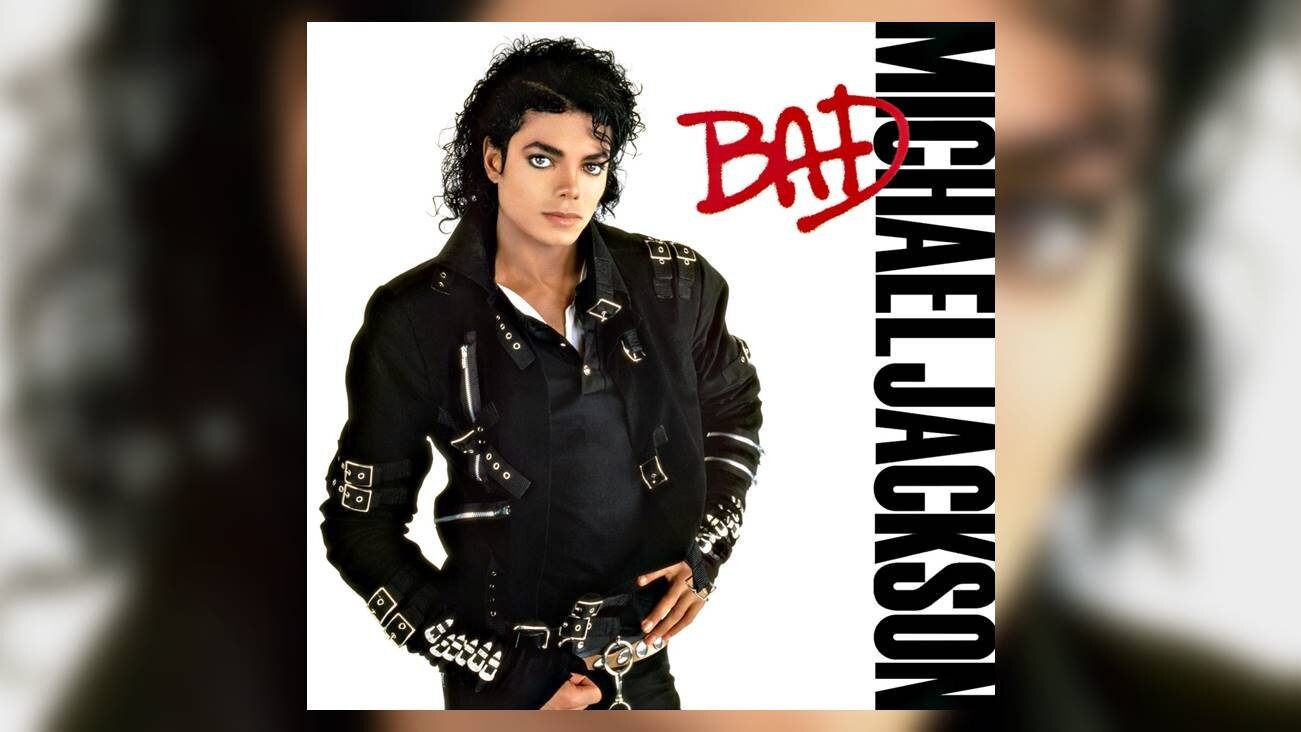

Happy 30th Anniversary to Michael Jackson’s seventh studio album Bad, originally released August 31, 1987.

Conventional wisdom has it that Michael Jackson reached his artistic peak with Off the Wall (1979) and Thriller (1982), and Bad (1987) was the beginning of a slow and steady decline. However, this intensely creative period is much better than its reputation suggests. Bad contains more solid pop classics than most greatest-hits compilations, a deeper bench than some may remember, and trailblazing visuals that expand upon Jackson’s legacy as the first genuine superstar of the video age.

Following up Thriller was no doubt a daunting endeavor (roughly 38.5 million copies sold at the time, seven Grammy Awards, and seven Billboard Top 10 singles), but Jackson enjoyed competing against himself—both commercially and artistically. This time around, his bold vision was to construct a pop album that would sell 100 million units and incorporate sounds the human ear hadn’t heard before. With those ambitious goals in mind, Jackson penned over 60 songs with plans of releasing 33 of them as a triple-disc set. Producer Quincy Jones, while enthusiastic about the influx of promising new material, suggested he trim it down to a single LP that would provide his listeners with maximum heat. Returning to his musical throne after a five-year hiatus, could Michael Jackson tilt the pop world off its axis yet again? The answer turned out to be a resounding yes.

In a quest for pop’s outer orbits, Bad combines the era’s latest studio technology with irresistible melodies that spark head-bobbing and hip-shaking motions of approval. The seamless blend of pulsing electronics and vintage soul on “The Way You Make Me Feel” channel the flirtatious spirit of “P.Y.T. (Pretty Young Thing).” “It’s a really intense shuffle,” said keyboardist Greg Phillinganes. “I remember how much fun I had laying down those offbeat parts, the bass line, all that stuff, and watching the expression on Michael’s face—he’d get that big grin that meant you had it.”

Reportedly written after Jackson got a speeding ticket headed to the studio, “Speed Demon” fuses leather-tough vocals, piston-quick bass lines, and revving Motorsport engines into an ear-scorching funk roadster.

The Stevie Wonder-assisted “Just Good Friends” may be the album’s least interesting chapter, but it mixes bubbly synths and Motown adolescent pop into a fizzy adaptation of Thriller’s “The Girl Is Mine.” “Another Part of Me,” notable for its appearance in Disney’s 1986 Captain EO attraction, is a glistening vortex of synth-funk, jazz brass, and neon colors. Interestingly, the kinetic dance-floor burner nearly lost its spot on the final roster to the fan-favorite outtake “Streetwalker,” but Jones made the right choice in convincing Jackson to keep it on Bad as it skyrocketed to #1 and #11 on Billboard’s R&B and pop charts, respectively.

Complementing those heavyweight grooves is Jackson’s willingness to give his top-notch collaborators an opportunity to bring out the best in him with their creative input. Much credit goes to ace musicians John Barnes, Chris Currell, and Paulinho Da Costa, whose cascading synths, tribal percussion, and rippling sitars aggrandize the exotic glow of "Liberian Girl." Jackson’s lead and harmony vocals are earnest and rich with feeling as he praises African beauty, a rarity in the realm of mainstream pop. “All of his stuff is so different,” Quincy Jones explained. “I mean, ‘Liberian Girl,’ who would think of a thing like that? It’s amazing. Just the imagery and everything else. It’s [an] amazing fantasy.”

Legend has it that Jackson and Jones considered high-profile vocalists Barbra Streisand, Aretha Franklin, and Whitney Houston as potential duet partners on “I Just Can’t Stop Loving You.” Unable to snag any of them, Jones recruited the relatively-unknown Siedah Garrett (co-writer of “Man in the Mirror” with Glen Ballard), who wasn’t aware of her new role until the day of recording. Despite the song’s complicated genesis, their dazzling vocal chemistry is executed so well it evokes memories of classic-period Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell.

The ferocious rocker “Dirty Diana” expands upon the predatory nature of “Billie Jean” as it plunges into the nightmarish abyss of celebrity fandom. When the titular groupie senses resistance from Michael (“My baby’s at home, she’s probably worried tonight”), she hurls a heart-piercing barb at his girlfriend over the phone (“He’s not coming back because he’s sleeping with me”). At the song’s dizzying climax, Jackson erupts in a flurry of hair-raising screams as longtime Billy Idol guitarist Steve Stevens delivers an electrifying solo that cracks like jagged lightning across a blackened sky.

On an album full of remarkable songs, “Man in the Mirror” is the emotional anchor and a breathtaking example of how great Bad is when all the stars align. The uplifting gospel/pop anthem reflects on society’s insensitivity toward others’ suffering (“I see the kids in the street with not enough to eat / Who am I, to be blind? Pretending not to see their needs”). As those heart-wrenching images bring tears to the eyes, Jackson and the soaring Andraé Crouch Choir invite you to be part of the cure (“If you wanna make the world a better place, take a look at yourself and make a change”). Rolling Stone later praised his 1988 Grammy Awards performance of the song “as majestic and definitive as the Motown 25 moonwalk.” Michael may not have written “Man in the Mirror,” but his emotional investment makes it as connected to his life as any he ever recorded.

Bad not only changed pop’s landscape by ear but also by sight with a tapestry of groundbreaking short films that remain profoundly influential and supremely ambitious. Loosely inspired by the tragic death of Edmund Perry, at the heart of “Bad” is Jackson’s character, Daryl, celebrating the end of his school semester before returning home to inner-city Harlem. His old neighborhood friends (led by a young Wesley Snipes) playfully tease him for his articulateness and goad him into joining their mugging crew. When Daryl decides not to go along with their plan to rob an elderly man, they accuse him of not being “down.” “Are you bad [black] or what?” Snipes asks. Daryl/Jackson’s method of answering this question—with the help of ace filmmaker Martin Scorsese and award-winning novelist Richard Price—is fascinating as he reinvents the possibilities of black identity from the zipper-laden leather bombers to the West Side Story street ballet movements. Some of Jackson’s bigger and flashier works may overshadow “Bad,” but it’s one of his most essential creations with an optimistic social consciousness that’s worthy of academic discussion.

Sarcasm is a powerful tool that Jackson uses on “Leave Me Alone,” which proudly thumbs its nose at the paparazzi’s overt and insidious bias. Jackson’s megastar popularity all but forced him to withdraw from public life by 1987, creating a deep mistrust of the media and a firestorm of outlandish rumors, some of which he orchestrated to be slightly eccentric while others drew blood. Director Jim Blashfield, known for his stop-animation on Talking Heads’ “And She Was,” spent three days filming Michael on 35mm camera before his team of animators cut and layered hundreds of images over a grueling nine-month period. The finished product sends the star through a funhouse of tabloid rumors—singing from a hyperbaric oxygen chamber, cruising through a shrine to Elizabeth Taylor, and performing alongside the Elephant Man’s bones—before a life-sized Jackson destroys the carnivalesque environment that once imprisoned him (à la Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels). For all its cinematic imagination and self-mockery, “Leave Me Alone” highlights the absurdity that sadly infested the duration of Jackson’s life.

Although “Thriller” is often considered the greatest piece of musical theater ever conceived for a pop song, it’s time to admit that the Colin Chilvers-directed “Smooth Criminal” is every bit as significant. Donning a crisp zoot suit with a mysterious armband that carried on for almost the rest of Michael’s life? Check! Wowing audiences by tossing a quarter effortlessly into the Club ‘30s neon-lit jukebox? Double-check! How about inventing a dance vocabulary that synthesizes Fred Astaire’s classic movements, James Brown’s sizzling footwork, and zany Looney Tunes animation all at once? Triple-check! Debuting an anti-gravity gangster lean before wielding a vintage Tommy Gun just as his capture seems imminent? You got it! On top of all that, these elements serve as the centerpiece of his 1988 feature film, Moonwalker, as well as a SEGA arcade video game of the same name. An intricate knitting of MGM musicals and detective noir, “Smooth Criminal” is, if not the ultimate Michael Jackson spectacle, then it’s certainly near the top of the list.

As the concluding chapter of the Michael Jackson & Quincy Jones saga, Bad set a new gold standard for pop music and entertainment. Commercially, the album shipped 45 million copies globally, yielded five consecutive #1 singles in America (“I Just Can’t Stop Loving You,” “Bad,” “The Way You Make Me Feel,” “Man in the Mirror,” and “Dirty Diana”), and dominated the Billboard charts in 25 other countries. However, Bad’s greatest achievement is Michael Jackson’s blooming creativity; not only did he co-produce the entire album but he also wrote nine of the final 11 songs and garnered worldwide recognition as music’s defining visual artist with an MTV Video Vanguard Award in 1988. Comparisons with Off the Wall and Thriller are unimportant, except for this one: Bad is a pure pop masterpiece that stands parallel with—and, at times, eclipses—its classic predecessors.

LISTEN: