Happy 25th Anniversary to Prince’s Chaos and Disorder, originally released July 9, 1996.

“I rock, therefore I am. I don’t need you to tell me I’m in the band…”

It had only been a decade since the Minneapolis-born-and-bred wunderkind Prince Rogers Nelson single-handedly redefined and dominated popular music and the cultural climate, becoming one of the most distinctive post-modern visionaries of the Eighties. Sonically, visually, and artistically, Prince’s touch was ubiquitously rich and shined brightly throughout the music world. Not to mention, he was the spearhead of a significant stylistic hybrid called The Minneapolis Sound, where mechanically-produced funk became fearlessly amalgamated with electronic music, new wave, punk, soul, experimental rock, and pop. A true non-conformist that refuted traditionalism on every level, he challenged people to question their own perceptions and inhibitions on gender, race, sex, and society.

As a musical disciple from the schools of Sly & the Family Stone, Betty Davis, Parliament-Funkadelic, Santana, and Jimi Hendrix, Prince realized that it was vital to create beyond what was typically expected from a black musician and dismantle all conventions that fueled the adversity placed upon them, even if it were to cost him everything in the process. As the Eighties progressed, his artistic evolution was more pronounced than anyone could have ever imagined, as he broadened and refined his musical palette, drawing heavily from jazz and syncopated funk idioms of the past while making them sound all of his own. Forging new creative depths and genre-blurring experimentation, Prince’s unabashed knack to outwardly explore often bewildered the mainstream pop and rock audience base he gained with his 1982 breakthrough opus 1999 and his 1984 commercial behemoth Purple Rain.

White mainstream rock purists who praised the masterful crossover impact of Dirty Mind, Controversy, 1999, and Purple Rain failed to truly immerse themselves in the escapist pop worlds that Prince was delving into, often overlooking the eccentric charm and musical audacity that defined his post-Purple Rain output. His core black audience still championed him as a sure innovator, but some couldn’t grasp the totality of his approach, as the landscape of black popular music was dramatically changing by the mid-1980s.

Several wrongly and lazily deemed his post-Purple Rain endeavors (sans 1987’s eclectic double-opus Sign O’ the Times, which also received some mixed reception upon its initial release) as aimless, artsy pop efforts that never reached the commercial-veering heights of their predecessors, solely criticizing his productivity and ambition. Many also naively accused him of abandoning his defining roots as the funk-pop-rock extraordinaire that sparked his ascension to mass rock-as-pop superstardom.

One key point that those detractors missed during this crucial period of Prince’s creativity and exploration was that art and culture must evolve beyond the context and confinements of its elements, before they reach their absolute exhalation. Like Miles Davis, Stevie Wonder and Joni Mitchell before him, Prince understood that true genius could be fully realized when one expanded the possibilities of their innovation and expression. He was not abandoning or disregarding his past discoveries at any point, but adding new dimensions, colors and narratives.

If one were to point to the span of landmarks he recorded and released during his cherished 1978-1988 run, the eleven albums (yes, including The Black Album) from 1978’s For You to 1988’s Lovesexy were largely ambiguous—each possessing their own atmosphere, space, and mystery. Progressive, ambitious, and freewheeling in their own right, they were extensions of where he was, with no certain clue or passage pointing to what his future was going to be. While he moved beyond the conventionality of popular music, rightfully leaving admirers and followers to constantly ponder his unpredictable turns, Prince withstood all perceptions and pretensions. He triumphed throughout the daunting era in which he reigned.

However, there was a catch: a new decade was brewing. How would he manage to withstand the challenges of the era that lay ahead? What step of artistic ground would he take next?

The '90s were both frustrating and inspired for the Purple One, who more than proved his artistic prominence of a decade before. While reinvention was very much at the brink of everything he aspired to achieve stylistically, adapting to the changing currents of popular music was beginning to impact his musical outlook. The hip-hop generation, a culture and style Prince infamously criticized, largely caught wind of not only the pop landscape, but his world. For many, including his established fan base, Prince wasn’t pop’s primal innovator anymore. Instead, they viewed him as a caricature of his former self, following trends of the day, while reaching in his arsenal of stratagems for inspiration. While it was never problematic for someone as musically proficient as Prince to come up with something uniquely his own, he preserved the changes with solid results.

After experiencing something of a commercial rebound with the severely-maligned soundtrack for 1989’s Batman, Prince opened the 1990s with a new band, The New Power Generation, and a trio of albums that possessed a rejuvenated distillation of his musical eclecticism with contemporary pop flourishes. These were the 1990 ensemble soundtrack to the limp film of the same name, Graffiti Bridge, 1991’s glitzy pop-soul of Diamonds and Pearls, and 1992’s ambitious semi-rock opera The Love Symbol Album. While he still managed to maintain commercial relevance in the realms of the pop landscape during the early '90s, there was something else brewing—a key moment that would alter the course of not only his career, but the major label system, as we know it today.

On August 31, 1992, Prince negotiated and signed a speculated $100 million contract with Warner Brothers, which rivaled two of his biggest contemporaries’ deals at the time: Madonna’s joint contract with Warners and Michael Jackson’s accord with Sony Music, both estimated at $60 million each. While the 1992 contract was an extension of a contract he signed with the label in 1977, it proved to be both detrimental and convoluted from the very beginning. One important passage in that contract, which notably didn’t even include a signing fee, guaranteed Prince a $10 million advance for each release, only if the previous release sold at least $5 million—in an attempt to reach or surpass the threshold sales of 1991’s Diamonds and Pearls, which sold an upward of 5 million copies.

For several industry observers, it was later concluded that this was a strategic way for Warners to motivate him to implement the same effort into his subsequent releases as he did for Diamonds and Pearls, by releasing albums less frequently and promoting them with viable singles and videos, as well as touring extensively. The problem was that Prince’s domestic and international sales were increasingly erratic at best. By 1993, he and Warners hit a mighty slump in their association, which caused a media frenzy.

Prince wanted to release more music as he wished while owning his master recordings. When Warners resisted and demanded that he comply with the standing agreement they had, Prince took another bold step. He relinquished his famous stage moniker, announcing that “it was owned and dead,” and then replaced it with an unpronounceable glyph that became his trademark. In addition to these dramatic events, he began to go out in public with the word ‘slave’ scrawled on the side of his face—his own way of fueling the controversies and tensions that surrounded his feud with Warners. He simply wanted out of the bureaucratic practices of the music business, at every cost.

Still, the man was as prolific as he ever was. In fact, the large volume of material he recorded from 1993 to 1996 found him exploring subtle artistic territory, slightly deviating from the conventions of his post-Lovesexy offerings from the early '90s. While the uniformity and spontaneity of his golden era remained unrivaled, he refined his succulent mastery of rock, funk, and soul with an enticing modern approach.

Among the three studio releases Prince released into the marketplace during his twilight years at Warners, 1996’s Chaos and Disorder is unquestionably the most revealing and pessimistic by design. Many of his dedicated fan base and critics alike commonly consider Chaos and Disorder an acquired listen, mired by the Purple One’s lesser material and masked as contractually obligated fare that freed the man from his former label, concluding their twenty-year association. The man who conceived it rarely had interest to discuss it in interviews or promote it (neither did Warners). When he did, he spoke modestly of it, never discussing its musical value, but rather its intention. Worst of all, it was the follow-up to 1995’s acclaimed, yet commercially disappointing The Gold Experience.

Given all the uncertainty and mystery that surrounded Prince during this tumultuous period, it would be easy for some to view Chaos and Disorder as a phoned-in mixed bag that he threw together in a week and intended to shelve. However, there was way more intrinsic detail that was buried under the surface. Prince hastily recorded a handful of the album’s material from February to April 1996, resulting in him delivering the final configuration to Warners for a summer release, in the midst of recording its then-untitled follow-up.

Forty-percent of the album consisted of leftovers from the Come and The Gold Experience-era sessions. He enlisted the same core musicians from his reconfigured New Power Generation band for the sessions, with a few surprise guests. Instead of relying on his eclectic approach, Prince stripped things down a bit. While there is indeed a certain polish and immediacy to the song craft, which was present in much of his greatest '90s work (1993-96), the grit and punch of the musicianship is what gives the album its overall raw edge. Amazingly, there is no overreaching sprawl or overriding theme to this album. This was a tightly-focused, grunge-oriented rock-funk collection that Prince himself could only come up with. It wasn’t perfect by any means, but the high consistency of most of the songs is solidly confounding, considering this was a compilation.

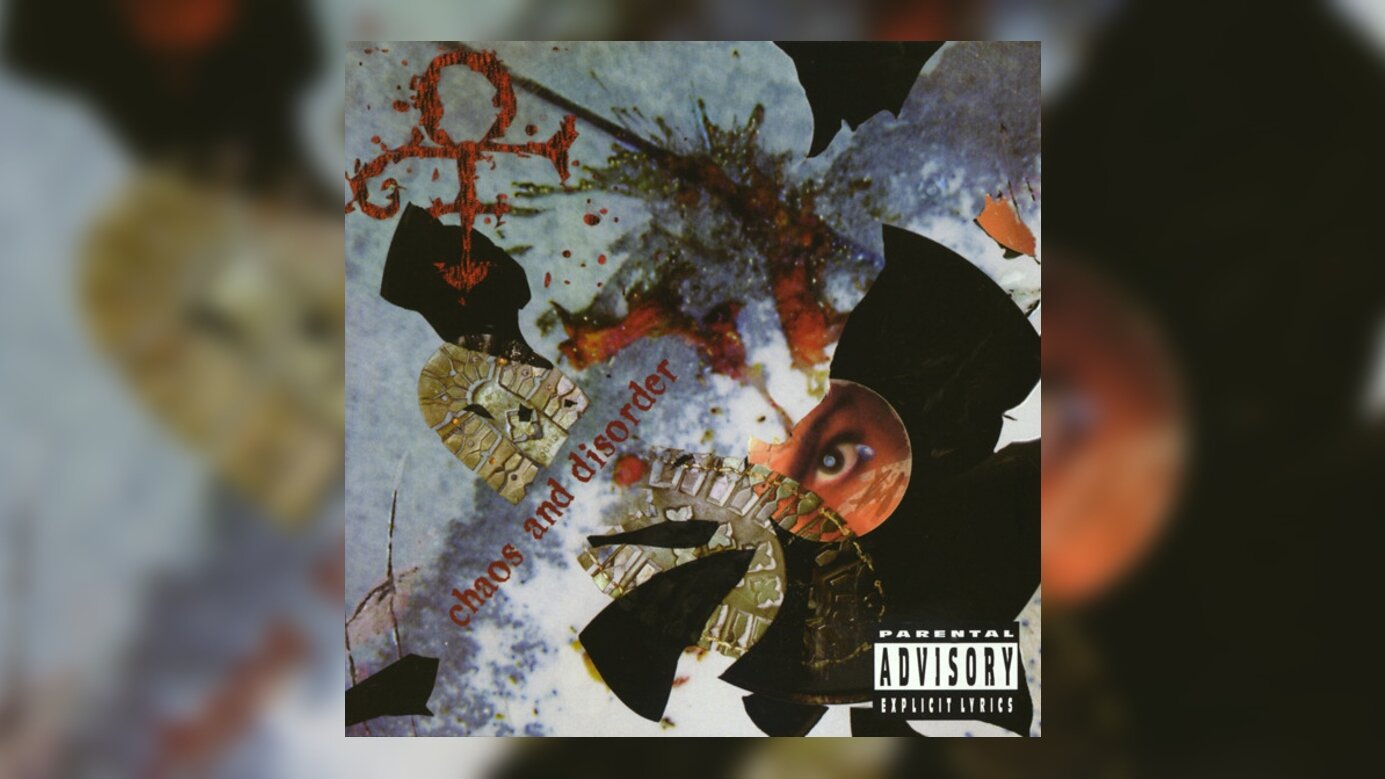

Even before you take the disc out of its jewel case, Steve Parke’s computer Xeroxed artwork offers abrasive insight into how bleak Prince’s world had become by the time he planned to leave Warner Brothers. Gone were the warm, gold-shimmered colors that defined the artwork for The Gold Experience. The liner notes bared this now-classic description, claiming that the music was “originally intended 4 private use only,” adding that “the original material recorded by the Artist 4 Warner Brothers Records – May you live to see the Dawn.”

The symbolism in the artwork revealed a lot as well. There is a cracked vinyl platter of 1999 that has been stomped to the floor, splatters of blood (even used in the design of his trademark glyph), a money-filled syringe, and photographs of a vault, recording studio, guitar collection, and an array of awards (all shot at the Paisley Park compound). The most disheartening illustration is the picture of a toilet with a human heart inside of it. Pretty cryptic and disturbing for a commercial release, but after all, this was the Artist’s bitter kiss-off to Warner Brothers. If he was going to leave, he wasn’t going to take any prisoners in the process. It was birthed from long-standing frustration and animosity in the first place.

In the album’s opening title song, “Chaos and Disorder,” Prince fires all barrels, offering a scathing critique on the changing dynamics of '90s post-modernism. At best, it can be considered nihilistic and introspective in the same distance, as he realizes things aren’t the same from when he came up in American society. He’s struggling to find his place in it, critiquing its attributes all at once. Weary and downright fed up, he sings in the rocking bridge, “I’m just a no-name reporter / I wish I had nothing to say / Looking through my new camcorder / Trying to find a crime that pays / I get hit by mortars, everywhere I go I’m loitering / Chaos and disorder ruinin’ my world today.” The tenacious, industrial rock of the musical approach compellingly fits the song’s jarring message on the jadedness of American society.

The Sixties-styled psychedelic rock of “I Like It There” boasted a catchy pop melody, with bassist Sonny Thompson and drummer Michael Bland masterfully interplaying with Prince’s tasteful guitar work. The song has him bidding a request for a woman’s sexual conquest. “Dinner with Delores” has a delicate, Seventies-influenced jazz-rock sensibility that has Prince metaphorically detailing his relationship with Warner Brothers in the form of a rather twisted, run-of-the-mill romance. A brilliant example of how Prince implemented double entendres in his songwriting, “Delores” was the album’s lone single, which was only released in the United Kingdom, peaking at #36 on the UK singles chart.

The bolstering “Same December” found Prince tackling race relations with a utopian vision, informing people to derive telepathically from a similar spirit and soul. While the bluesy “Zannalee” and country-tinged rock of “Right the Wrong,” which dealt with the social injustices committed against Blacks and Native Americans, gave the album some admirable stylistic variation, they both compromised the album’s momentum, after the remarkable stretch of the first four songs.

The six-minute “I Rock, Therefore I Am” featured an infectious hip-hop funk groove that dealt with nonconformity to the perceptions of others when it comes to identity. Along with “Same December” and “Right the Wrong,” “I Rock” is unquestionably the most sociopolitical song on this album, where Prince compellingly brings up racial injustice and how Black culture has been exploited by those who have no mere understanding of its rich history and experience.

Perhaps the album’s defining centerpiece is the one-two punch of “Into the Light” and “I Will,” which possesses an epic power rock-pop sensibility, before descending into a smoothed-out, slow grinding groove. “Into the Light” has a deeply spiritual resonance that echoes the theme of redemption and rebirth that was embraced on “Gold,” the title track to 1995’s The Gold Experience. It has been said that Prince wrote and recorded the song as direct correlation to author Betty Eadie’s 1992 book Embraced by the Light, which described her near death experiences. Both “Into the Light” and “I Will” feature killer background vocal work from soul vocalist Rosie Gaines and blissful saxophone solos from the late great Brian Gallagher.

The bouncy funk workout “Dig U Better Dead” dealt with his choice to refute the evil doings of the record business and become his own agent. The album’s concluding song; the harrowing “Had U” was poignantly placed at the end for a significant purpose. With its dirge-like arrangement, the brief number serves as his scathing farewell to Warner Brothers and the legacy he built during his tenure on the label. There is no real vivid lyricism to the song, except two-worded sentiments that allude to his evolving emotions toward the label. Many have speculated that “Had U” was something of a downer parallel to the spirited A cappella title piece that opened his 1978 debut album, For You, which was his introduction to the music world. However, Prince himself never confirmed it. He sings with an abundance of remorse and regret, like a divorcee who is torn from the strains of a messy split.

In retrospect, Chaos and Disorder marked the then-farewell of Prince’s twenty-year association with Warner Brothers, before he later reunited with the label, striking a landmark deal in 2014, and winning control over his back catalog. In late 1996, the self-proclaimed ‘slave’ would celebrate his emancipation from Warners, embarking on a myriad of business practices and musical journeys that would further cement and complicate his legacy as a pop vanguard.

Chaos and Disorder managed to reach number twenty-six on the Billboard 200 album chart, while failing to chart on Billboard’s Top R&B Albums chart. The album was met with mixed to mostly negative reception upon its initial release in the summer of 1996. It’s no mere surprise that the album tanked commercially, as it was a stifling experience for Prince—both musically and metaphorically. He wanted nothing to do with it, eagerly awaiting its eventful end.

But if one were to overlook the album’s tumultuous history and place it solely in the context of Prince’s rich musical lexicon, many will find it to be a riveting testament to his viability as a rock extraordinaire, who could hold his own with the most respected and well-regarded. It isn’t a wall-to-wall knockout that stands alongside Sign o’ the Times, Dirty Mind, or Lovesexy, but he didn’t envision it as that. It is one of the criminally neglected gems in his '90s output that has held up better than it was expected to.

Personally, I’ve never quite understood the slighted reverence that Prince received and continues to garner when it comes to his credibility as a rock musician. I could probably conjure up several reasons why he isn’t more revered in the annals of rock giants, but it’s simply unfortunate to think about. I’ll put it like this: he was more than just Purple Rain. The man embodied the fiery, attitude, and spirit of rock. It was his Midas touch—the very distinction that would fuel his audacity to be his own man and live by his own rules. Not to mention, his supreme virtuosity as a guitarist possessed a certain ebullience and wit that was uniquely his own.

While Prince never understated his innate rock underpinnings at any point, Chaos and Disorder remains an interesting, yet rousing portrait of one of rock music’s visionaries crafting idiosyncratic music, in the shadow of his darkest hour.

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2016 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.