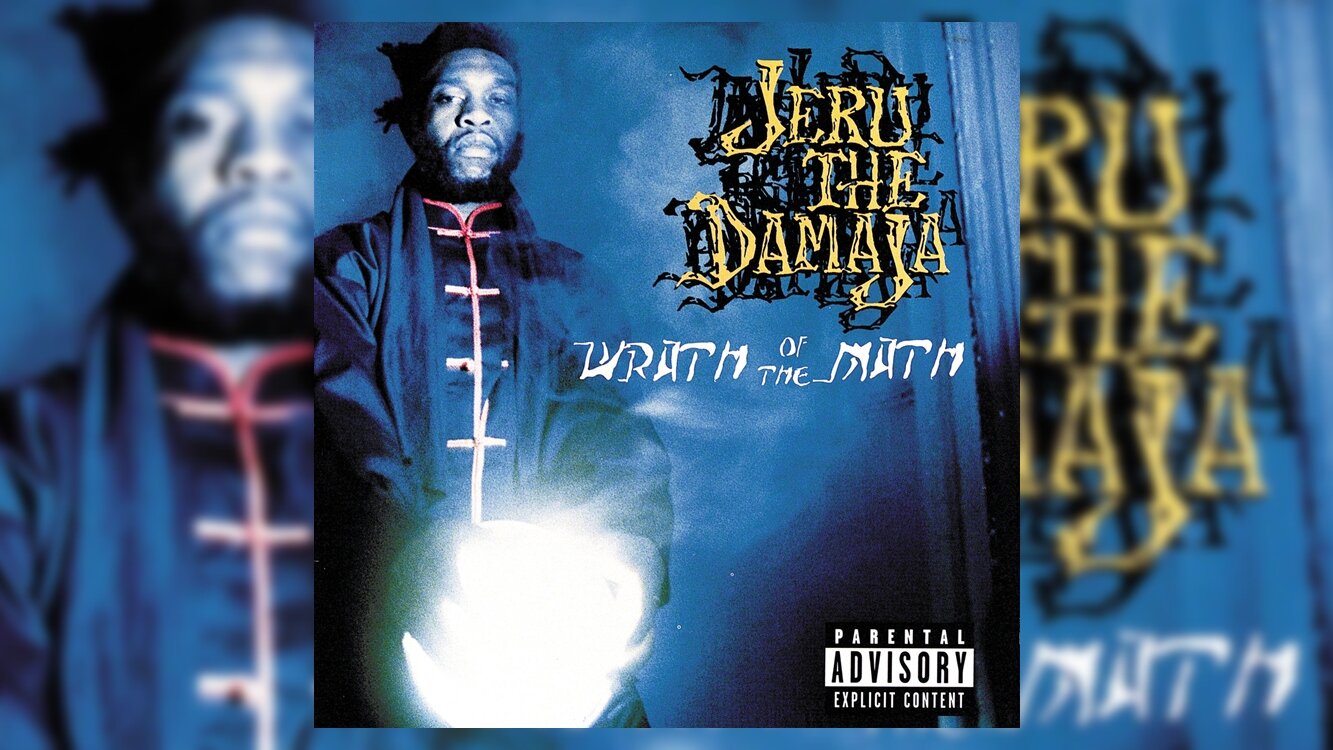

Happy 25th Anniversary to Jeru the Damaja’s Wrath of the Math, originally released October 15, 1996.

Someone is always battling for the “soul” of hip-hop. Since the first rap was recorded, there have always been those who fought to keep the musical art form “pure” in the face of the corrupting influence of big money and the record industry. The tenets remain the same throughout the years. Don’t follow commercial trends. Don’t compromise artistic integrity for the sake of record sales. Don’t sell out to the mainstream.

These cries were perhaps the loudest in the mid-’90s, as the larger record labels were figuring out just how much money they could make selling hip-hop music. For all intents and purposes, there were two “faces” of hip-hop music during this period: the New York-based Bad Boy Records and the Los Angeles based Death Row Records. Bad Boy, following the lead of its founder Puff Daddy, essentially created the “shiny suit rap” genre: lyrical bottle-popping over easily recognizable samples from past pop records. Death Row Records, ruled by Suge Knight, was synonymous with gangsta-ism on wax.

During this era, Soundscan numbers were king. MTV and daytime radio were beginning to welcome rappers into the fold. Rap music was on its way to becoming the highest selling musical genre. Hip-hop music looked like it was becoming an unstoppable force, but with the combination of rampant materialism and bloodshed on record, was it happening at the cost of its soul?

In 1996, Kendrick “Jeru the Damaja” Davis waded into the fray. Jeru had already made himself known during the early ’90s as an affiliate of Gang Starr, the legendary duo comprised of Keith “Guru” Elam and Chris “DJ Premier” Martin. Jeru had appeared on Gang Starr’s 1992 album Daily Operation and 1994’s Hard to Earn. He also had released a classic solo joint on his own, his 1994 debut The Sun Rises in the East, which boasts hip-hop anthems like “Come Clean,” “D. Original,” and “You Can’t Stop the Prophet.” He’d positioned himself as a self-styled protector of the people, ever ready to safeguard them from the rampant ignorance and materialism that was becoming so prominent.

On his sophomore album Wrath of the Math, Jeru takes aim at those he perceives as the enemies of hip-hop, including the Bad Boys and Death Rows of the world. Also central targets are New York City’s Hot 97 and commercial radio, and the record labels that he believes are complicit in degrading the culture.

Wrath is at its best when Jeru is bent on defending the honor of hip-hop music. Much of the commentary is on the nose and not particularly subtle, but his strength of conviction behind the rhymes sells it. The album reflects the deep frustration and anger many felt toward what hip-hop was becoming, with Jeru playing the role of the angry prophet, looking to cast the thieves out of the temple.

DJ Premier accompanies Jeru on this holy quest, handling all of the production duties for the album. Primo was in the midst of a serious hot streak in 1996, which really stretched back all the way to Hard to Earn. Besides providing all of the beats for Gang Starr’s fourth LP, The Sun Rises in the East, and Group Home’s underappreciated Livin’ Proof, Primo had been producing a non-stop stream of heaters for artists like Nas, KRS-One, Das EFX, Bahamadia, and M.O.P. He’d also been working with rappers like the Notorious B.I.G. and Jay-Z, two artists making the type of music that was drawing Jeru’s ire. Years later, Primo would talk about how this album indeed made working with Bad Boy kinda awkward. Regardless, Primo does yeoman’s work on this album, lacing Jeru with a largely high-paced and rugged soundtrack for him to crush his musical enemies.

The track “One Day” is about as unsubtle as it gets, with Jeru having to track down “hip-hop” after it’s taken hostage and forced into a Versace suit. After storming the gates of Bad Boy Records and beating up Jay Black (head of marketing and promotions for the label at the time), Jeru flies west to recover hip-hop from Death Row’s clutches. The details on how he pulls all of this off remain hazy.

“Bullshit” functions as Jeru’s version of Black Sheep’s “U Mean I’m Not?,” parodying everything he’s come to dislike about the state of hip-hop. He dreams of himself in Tahiti, draped in diamonds, surrounded by beautiful Uzi-packing women, drinking a martini, with billion dollar jets and million dollar yachts at his disposal. Its over-the- top ridiculousness is the point of the record, but the lyrics also reflect the backdrop of pain pervasive during much of that era. This dream version of Jeru speaks on how he got into rap after surviving selling crack while his friends ended up incarcerated, and rapping about material gains turned out to be his way out of poverty: “Fuck being civilized, I got dollar signs in my eyes / One day I’ll fall but for now I’ll rise.”

The album’s lead single “Ya Playin’ Yaself,” is another direct dig at commercial rap. Over a flipped, sped-up sample of New Birth’s “You Are What I’m About,” which, not coincidently, was used by Junior M.A.F.I.A. for their biggest hit “Player’s Anthem,” Jeru again takes thugged-out rappers to task, with lines like, “Everybody's psycho or some type of good fellow / But me? I keep it real, that's all swine like Jello / Don't drink Cristal, and I can't stand Mo / Never received currency for moving a kilo / Or an ounce, make 'em bounce to this fake-pimp-free flow /I never knew hustlers confessed in stereo.” He also singles out record label executives that promote these artists, who talk big but do little to truly empower themselves or their artists: “If you got so much cheese, where are the Black distributors / And these record labels shaking them down like mobsters” and “Asses shake, bottles pop, the government is breaking down you fools / You work all week and give the Devil back his jewels.”

Wrath is bookended by two separate previously released tracks, but flows well with the album. The album’s opening track “Tha Frustrated Nigga,” was first heard on the 1995 Pump Your Fist compilation, and sets the tone for Wrath. A slow grooving horn loop allows Jeru to vent his irritation at the morally bankrupt American system that continues to marginalize Black people and culture. The album ends with “Invasion,” which first appeared on the two-volume New Jersey Drive soundtrack, an effectively incredulous ode to racial profiling by police officers. He eloquently describes the crushing and demoralizing effect that police harassment has on the Black community: “When I was young, I used to shoot for the stars / But got shot down by demons in patrol cars.”

The album occasionally falters. First is when Jeru attempts “sequels” to his previous tracks. “Revenge of the Prophet (Part 5)” serves as the sequel to the superior “Can’t Stop the Prophet.” To my knowledge, there are not three other unreleased installments to the story floating around out there. It’s one of the few cases where Jeru’s lack of subtly is a clear hindrance to making dope music. “Physical Stamina” is a similar misstep, but here it’s due to an extremely rare case of DJ Premier misfiring on the production end. Like its predecessor “Mental Stamina,” it features Jeru and Afu-Ra trading mini-verses back and forth, but the beat is a cacophony of keyboards and weird electronic sounds, and it’s nearly unlistenable.

“Me or the Papes” and “Not Your Average” are also problematic. Both utilize the trite “gold digging groupie is out for my money” narrative and the simplistic “queen/whore” dichotomy. Both themes are dated relics and both tracks waste spectacular Primo production.

But these are just a few blips on Wrath. The album also features a few straight-ahead lyrical explosions by Jeru. Songs like “Whatever,” “Scientifical Madness,” and “How I’m Living” demonstrate that Jeru’s lyrical sword remained sharp, and he’s just as good at the “rip a sucker MC” track as anyone. He also doesn’t save his venom for just Bad Boy and Death Row-related artists. On “Black Cowboy,” he harshly responds to the Fugees, after Pras randomly dissed him on their track “Zealots.” Over a sinister piano-loop, evocative of a proto-Western theme song, Jeru challenges them with “When I step to you don’t seek refuge / Make it happen, fuck the rapping.” The genesis of this mini-feud remains a mystery, but it did produce some entertaining music.

“Too Perverted,” another standout track, is a mesh of lyrical pugilism and bile towards record label politics. Over simple keyboard hits and a spare baseline, Jeru raps, “I pierce flesh and strike nerves like acupuncture / Or acupressure, feel the wrath of my mathematics / Kinetics, you need a local anesthetic / ’Cause your system has acquired an immune deficiency.”

Wrath of the Math was the last Jeru and DJ Premier collaboration. After Wrath, Jeru laid low for a number of years, periodically resurfacing to release a project, but never to much acclaim or attention. Primo continued to be a highly sought-after producer, and still works steadily to this day, mostly working with hip-hop artists outside of the mainstream or overseas. Bad Boy and Death Row continued to rule into the late ’90s, and Bad Boy even into the ’00s, until they both collapsed under their own weight.

History is written by the winners, and winners have written that the shiny suit and the thugged-out era were great for hip-hop music. They point to colossal sales figures and commercial placement and “Now!” music compilations. They’ve decided that anyone who criticized their success was a hater or irrelevant or mad because they were broke. And yet there are still those who persist to fight for hip-hop’s soul against forces they believe are corrupting it. The names have changed, but the game continues.

Note: As an Amazon affiliate partner, Albumism may earn commissions from purchases of vinyl records, CDs and digital music featured on our site.

LISTEN via Apple Music | Spotify | YouTube:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2016 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.