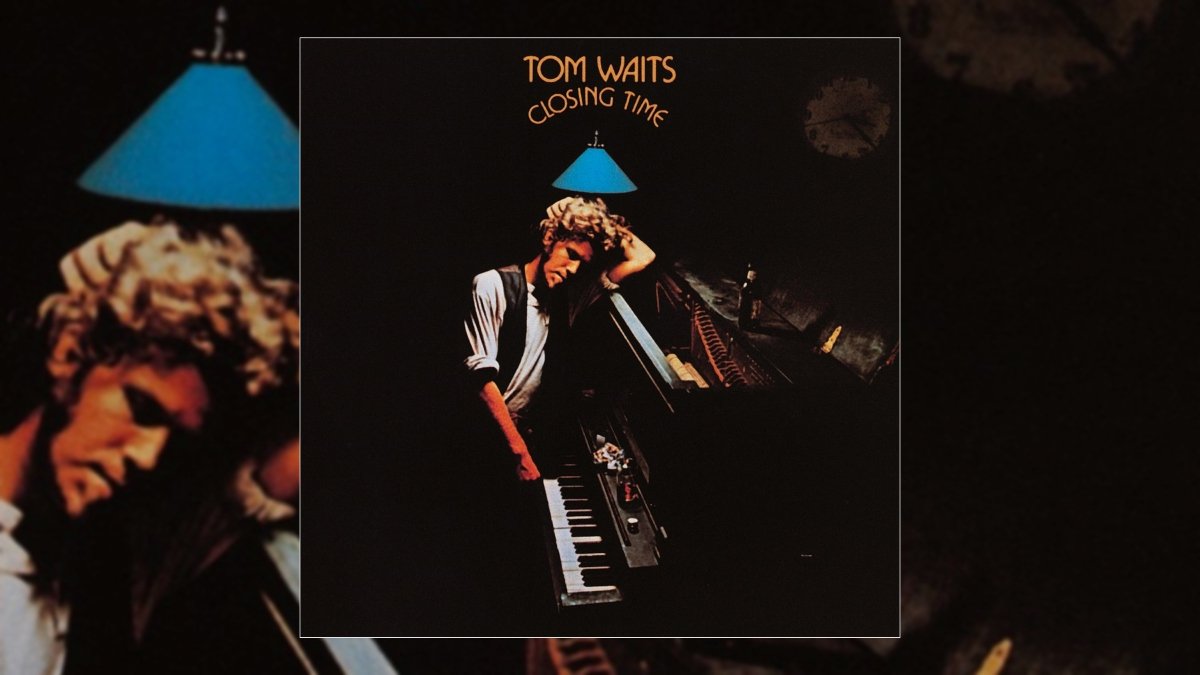

Happy 50th Anniversary to Tom Waits’ debut album Closing Time, originally released March 6, 1973.

The first time I heard Tom Waits’ debut album Closing Time was on the first night I spent with the man who would become my husband. I knew some Waits—the dry rasp of “Step Right Up” and the drizzle-drenched back alley dizziness of “Rain Dogs.” But as we sat alone in his living room, drinking rose hip tea at 2 a.m., the longing was palpable and unattainable. I was seeing someone else at the time, so Ian and I pretended to just be friends, neither of us wanting to admit that there was something else stirring. He put on Closing Time. The only light in the room was from the stars and the kitchen.

This was not the Waits I knew, the too-cool swagger I carried in mixes on my Discman to writing workshops. This was something far more vulnerable. Heart-cracked, paperback poetry set on melodies soaked in rainwater and a lonely night’s last drink. No pretensions. No sarcasm. Just a certain authenticity that only Waits can bring. Because while Waits’ persona has changed from bar balladeer to the Underworld’s carnival barker, he never approaches his music from an inauthentic place.

The album opens with “Ol’ 55,” a song that is so pure and lovely and perfect that it’s almost impossible to put to words how perfect it is. It builds into the chorus like a sunrise, you feel it swelling in your chest, but it never quite gives you the relief. The first two choruses each split into two parts, giving each section the feeling of its own bridge, and with the repetition of the first verse in the third, Waits captures a hyper-specific piece of what first love really feels like. This is not some bland declaration of “Wow, isn’t love, like, nice and stuff?” It is the delicate threads of bliss and melancholy, and peace and sadness, all woven together. It wouldn’t be until The Replacements “I Will Dare” that the atoms of love would be dissected as astutely as what Waits had done here.

(Side note: The Eagles cashed in hard on this one, because they’re assholes, but money cannot buy emotion, and with Don Henley’s voice, this song might as well be a sentiment scrawled on a box of half-off Valentine’s Day chocolate-flavored candies from the dollar store.)

Waits’ commitment to intensely precise emotions carries through into “I Hope That I Don’t Fall In Love With You.” Because we’ve all felt the tug of our hearts towards someone it might be too complicated to love. Because sitting on Ian’s couch, I knew that falling for him would mean making a choice between a relationship that had made me comfortable in the dull predictability of it, and taking a leap into a new unknown. Waits spelled that out for me, and as I played this song later, I listened to him. “I think that I just fell in love with you,” he croons at the end. He was right. Music usually is, if you listen close enough.

(Natalie Merchant covered this one. Bless her heart.)

Listen to the Album:

There are usually two types of people: those who prefer “Rosie” and those who prefer “Grapefruit Moon.” They’re a sister pair of songs, longing and lonely, slow and aching and meant to be played alone at midnight. I prefer “Rosie.” There’s something about the chord progressions as Waits slides into the chorus that twist up my insides like wringing out an old bar rag. “Grapefruit Moon” has its charms, of course, but it’s a little more maudlin, lyrically and musically. Waits’ voice drags ever-so-slightly, as though the album was recorded all in one take and he’s starting to tire.

I firmly believe that if you can get through “Martha” without crying, your heart is made of stone. I usually break when he gets to “Martha…Martha…I love you, can’t you see?” Again, he has put to music a defining moment in any romantic’s life, the realization that maybe the one you loved the deepest and the hardest isn’t the one you are meant to be with.

But it’s not all heartbreak and empty pillows. Coming on the heels of “Lonely,” “Ice Cream Man” is a happy and much-needed reprieve. With a dreamy, child-like intro and outro, it’s such a goofy song, but the warm percussion keeps a jazzy time under spicy guitar licks, all topped off with two minutes worth of Waits’ pattering double-entendre. I’ve always found Waits immensely sexy and I think this song is part of it.

(Screamin’ Jay Hawkins covered this one and it is amazing and filthy and hysterical.)

All albums have the fat that can be trimmed and, while pleasant enough, “Midnight Lullaby” and “Old Shoes (& Picture Postcards)” have a Waits-esque sound, but lack the grit that separated Waits from his other L.A. contemporaries. And the album winds to a close with the title track, an instrumental musing that closes the curtains, puts away the glasses and gently tucks you into bed.

After that first night with Ian, I played Closing Time for my boyfriend, Aaron. He shrugged and remarked “He can’t sing.” I think I knew in that moment that it was over. Eleven years later, Ian and I danced to “Little Trip to Heaven (On the Wings of Your Love)” as our first dance at our wedding. There was no better song to define our journey and to send us off on the next road of our life together.

I don’t listen to this album much anymore. It’s too tender. Each listen feels like it needs to be in a more sacred space than, say, riding the bus or washing the dishes. But in the early days of #RecordSaturday, I played it, and I cried sweet tears as I typed out my comments. Because this album, like The Queen Is Dead and Excitable Boy and Pretzel Logic, fundamentally changed the course of my life. It may not hold up as well musically—its 1974 follow-up effort The Heart of Saturday Night is a more refined, more listenable album—but it is like a well-loved photo album, a diary taken out and read a few times a year, a happy memory revisited.

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2018 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.