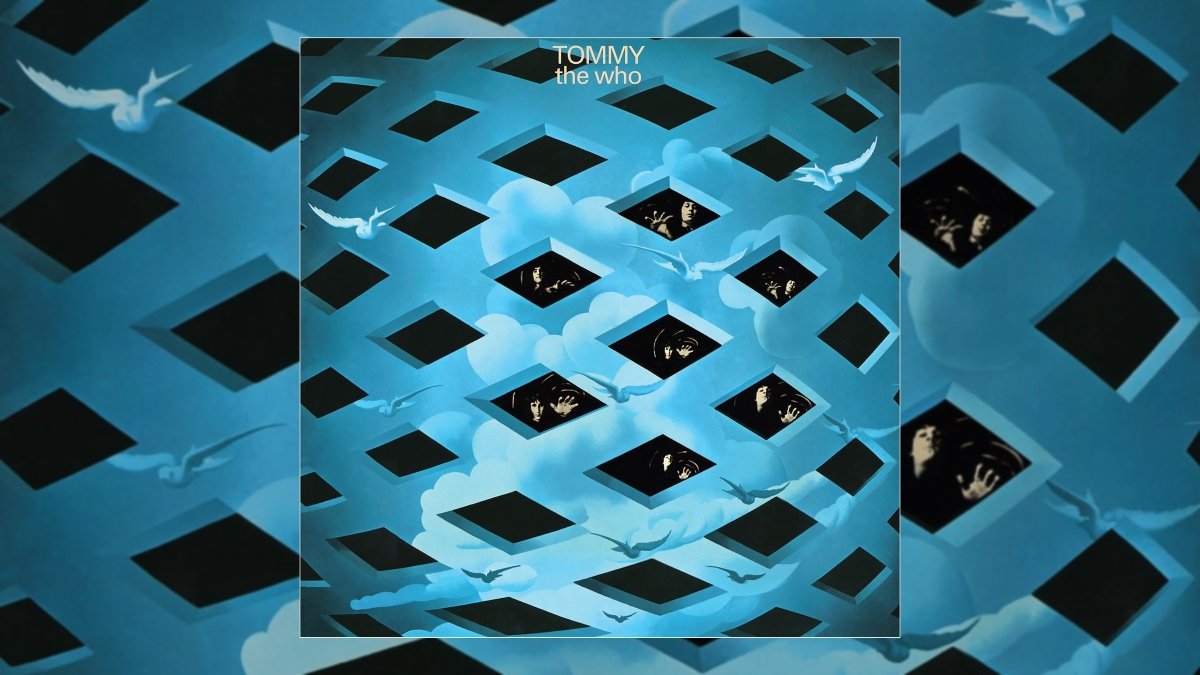

Happy 55th Anniversary to The Who’s fourth studio album Tommy, originally released in the US May 17, 1969 and in the UK May 23, 1969.

Over the years, The Who’s Tommy (1969) has gotten condensed into a narrative: Pete Townshend wanted to make serious art out of rock and roll, and he conceived of the rock opera. This is one part of the story. But, in this telling, something gets missed: this tension between rock and experimentation is a source of meaning on Tommy. The experimentation isn’t about doing fancy things for the sake of doing fancy things. Tommy is experimental because it asks us to see the world in a new way.

Consider the run from “Amazing Journey” through “Christmas.” After “Amazing Journey” takes a dive into Tommy’s consciousness—the first time on the record that we hear from the titular character, rather than the adults around him—“Sparks” treats us to an inward, instrumental journey. Rather than try to describe what Tommy, a deaf, dumb, and blind child, feels, Townshend relies on abstraction: a confounding, meandering poem of an instrumental song. “Sparks” gives the listener the chance to make a good-faith effort to understand Tommy, against the backdrop of the instrumentation, rather than needing to wonder whether Townshend got it right.

Then, after a (frankly unnecessary) detour through “Eyesight to the Blind,” we hear Tommy’s family lament that the boy doesn’t know that it’s Christmas. He doesn’t know religion or prayer as they understand it. On the heels of “Sparks,” it simply sounds idiotic: they are denying the swirling, beautiful mass of Tommy’s consciousness—represented by that sonic abstraction in “Sparks”—in favor of one narrowly defined spiritual life. From a musical perspective, “Christmas” is one of the few dyed-in-the-wool rockers on Tommy; it’s catchy and represents The Who at the height of their powers. It’s so tempting to want an album full of songs that sound like “Christmas.” Townshend is asking us to put that away, resist its comfort and its power, in favor of something unknown. It is an enormous musical and cultural risk, and I love it.

I’ll admit that, in the past, I’ve argued that Quadrophenia (1973) is the superior Who album. It leans more heavily into the band’s instrumental expertise and has a more cohesive story. (Indeed, Tommy’s narrative incomprehensibility is a frequent complaint about the album). But the weirdness of Tommy’s sound and story is a feature, not a bug. The band is asking us to listen differently.

They do this spectacularly. The musical diversity on Tommy is an unbelievable achievement. “Overture” is a divinely cohesive instrumental track that forecasts the rest of the record; John Entwistle’s contribution “Cousin Kevin” is gnarled and petrifying in its depiction of Tommy’s abusive uncle, and the climactic “Listening to You” theme is the most transcendent music The Who ever created. While it’s not The Who doing what they do best—smashing guitars and banging power chords—it is, puzzlingly, them at their best.

Listen to the Album:

But to what end? What’s Townshend’s grand message that required this diversion of form?

That’s a hard question to answer. Townshend’s descriptions of border on nonsensical in that unique way that late-Sixties spiritualism tends to. Much of it is rooted in the teachings of Meher Baba, an Indian spiritual master that Townshend followed. As the juxtaposition between “Sparks” and “Christmas” indicates, the opera asks the public to reject the judgments, materialism, and hierarchy that defined Western culture at the time (and today).

Notably, when the public in Tommy listen to the protagonist’s teachings—foregoing material wealth and drug use in favor of the spiritual abstraction promised by “Sparks” and Tommy’s previous disability—they revolt. They threaten Tommy. In the album’s final moments, he retreats into himself, the nebulous soup that we associate with his plead for connection and salvation, singing his prayer for unification. The thesis, ultimately, is that people are not ready for what Tommy (or Tommy) has to say.

This might seem perplexing for a record as well-beloved as this one. But it’s not beloved for its message; it is remembered as a landmark in pop music—elevating the genre of rock and roll and affording it cultural capital. The purpose of that change in form—the theory of social change—has been lost in favor of a narrative about gaining status. Once again, we’ve rebelled against Tommy.

Listen: