Happy 30th Anniversary to The Lemonheads’ sixth studio album Come On Feel The Lemonheads, originally released October 12, 1993.

Come On Feel The Lemonheads narrowly missed never getting made. It’s 1993, a gorgeous, blindingly sunny day in Los Angeles, and Evan Dando is moping around the pool at the Chateau Marmont, nursing a raw throat. A journalist from Q magazine has come to interview him about his band’s forthcoming album Come On Feel The Lemonheads, and all he can do is scratch lone words and brief phrases onto a little notepad in response. His demeanor is melancholy—but possibly darker—and by way of explanation for all of it he scrawls: “Substance Abuse.”

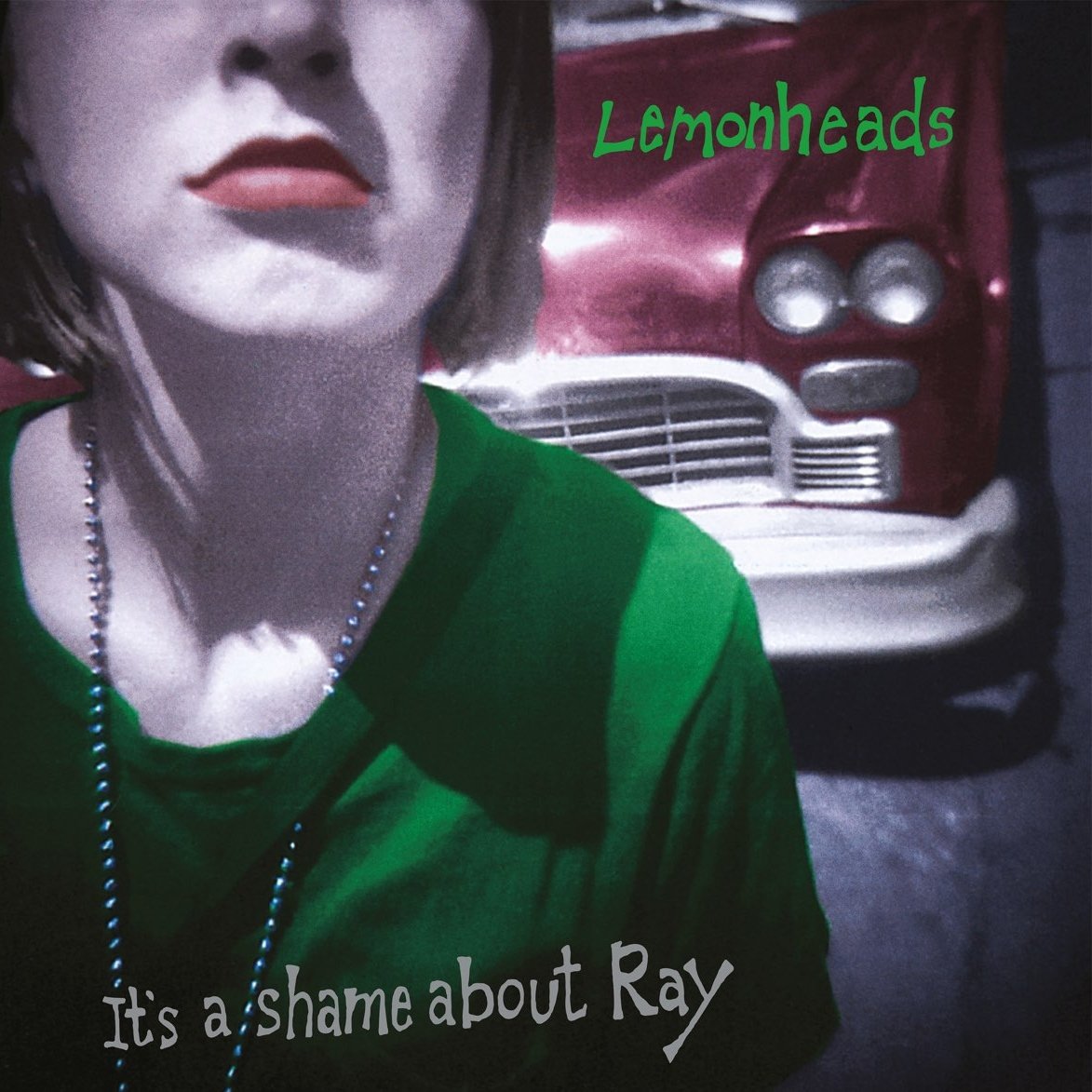

Under pressure to follow up the Lemonheads’ acclaimed previous album It’s A Shame About Ray (1992) with something even better, Dando choked in the studio and went on a two-week crack binge, damaging his throat. The crack smoking, he explains, is a habit he recently picked up at the Viper Room, where River Phoenix would famously and coincidentally die of a speedball overdose not long thereafter.

Meanwhile, back at Cherokee Studios in Hollywood, Dando’s bandmates bassist Nic Dalton and drummer David Ryan had recorded their parts without a hitch, as had Come On Feel’s cast of extras, including Belinda Carlisle, longtime collaborator Juliana Hatfield, and pedal-steel player Sneaky Pete. But when Dando tried to sing, he just couldn’t get it to work, and so he turned to drugs as a temporary salve. In truth, it wasn’t particularly new behavior. "I've been smoking heroin and cocaine for a long time,” he admitted to another journalist from Vox that same week. “But things have got heavier over the past few months, especially when I've been in LA.”

It’s easy to understand why Dando would experience pressure on the heels of It’s A Shame About Ray. It’s a tight, concise album about languor—chilling out, loafing about, hanging around; a masterful, alt-rock encapsulation of the uncertainty and ennui felt by young people of any era, but particularly the slacker early-’90s. At the same time Dando created this timely masterpiece, he was gaining an unfair reputation as a dippy hippie with a penchant for getting high and getting by on his good looks. (“Evan Dando is a good-looking guy with more luck than talent and more talent than brains who conceals his narcissism beneath an unassuming suburban drawl,” wrote Robert Christgau cattily.) For a lot of people, this would be fodder for a fuck-you attitude, but Dando always came across as the type to twist himself into something more relatable and accommodating to compensate for his above-average looks and people’s resentment and dismissal, leading to self-abandonment. Hence, the drugs.

Both Come On Feel The Lemonheads and It’s A Shame About Ray were mostly written in Australia, when Dando was on a slightly different sort of bender. He had already formed the Lemonheads after his one semester in college and was inspired by the neon-yellow candy that was “sweet on the inside and sour on the outside.” By 1991, the band had made four albums and were touring Australia when he met fellow musician Tom Morgan as well as future Lemonheads bassist Nic Dalton. After the tour, Dando returned to Australia in the fall of ’91 and spent the Aussie summer surfing and doing loads of Ecstasy (though speed factored in as well).

Morgan, frontman of the Sydney band Smudge, became Dando’s principal songwriting partner and the friends Dando made in the Sydney music scene would populate the cast of It’s A Shame About Ray. (“I met all of these amazing people down there who inspired me and kind of saved my life,” Dando told Interview of his Australia experience.) When I ended up seeing the Lemonheads play a tiny club in Germany on their Come On Feel The Lemonheads tour in the summer of ’94, Dando was still traveling with this colorful crew of Aussies, including Smudge drummer Alison Galloway, whose Ecstasy trip had inspired the song “Alison’s Starting To Happen.”

Listen to the Album:

When Dando returned from Australia to the United States in 1992, the Lemonheads began recording It’s A Shame About Ray in Los Angeles with the Robb Brothers, with Dando hanging out with Johnny Depp (future owner of the Viper Room) in his off time. Come On Feel The Lemonheads was to be a near-replication of this process in 1993 (it features more songs by Dando and Morgan and was again produced by the Robb Brothers) except for Dando’s unfortunate crack binge. Although the Lemonheads were ultimately able to complete Come On Feel in the studio, Dando’s addiction would taint many a live performance (though the show I saw in ’94 was fairly tight), and the Lemonheads went on a seven-year hiatus beginning in 1998.

As Dando feared, Come On Feel The Lemonheads is not as perfect an album as It’s A Shame About Ray, but it’s still respectable. (It even peaked at #56 on the Billboard 200.) While so much of Ray’s genius lies in its conciseness, Come On Feel stretches on for an indulgent 54 minutes (though a lot of this is owed to the 15-minute “Jello Fund” tacked onto the end). It’s a bit uneven, but it contains some big, soaring power-pop gems and plenty of artful, introspective moments to make up for its minor sins. The album is also highly aware of the Lemonheads’ newfound status as alt-rock darlings, flashing a charming, sparkle-toothed wink at fame, as well as being honest about its darker, gloomier underside (“Paid To Smile”).

Come On Feel The Lemonheads opens with “The Great Big No,” showcasing the band’s signature jangle which then morphs into something bigger, warmer, and pulsing around the edges (one review called it “almost like shoegaze,” and that’s indeed true). There’s a gorgeous interlude where the song dissolves into a fuzzy cacophony and Dando’s and Juliana Hatfield’s voices merge together in shimmering harmony (though their voices together are never not magic, really). “Lover don’t turn your head,” they entreat each other with increasing urgency.

“That one [“Great Big No”] started as a parody of a '70s song,” Dando told Songfacts in 2019. “It was like a cover of a parody—the beginning is making fun of some '70s tune. But then after a while, we started getting really into it and finished it. That's a co-write with Tom Morgan. It's a song about disappointment and nothingness.”

While part of what contributed to the Lemonheads’ unflattering reputation during the Ray era was their grating pop-punk cover of “Mrs. Robinson,” they got it right the second time around with the cover they chose for Come On Feel. “Into Your Arms” was initially performed by bassist Nic Dalton’s former band the Love Positions. The original is stripped-down and lo-fi twee, and the Lemonheads injected it with some serious power-pop treatment. Its corresponding video capitalized on what Blind Melon’s “No Rain” had already proven to be a winning formula: hot hippie dudes cavorting in a field, looking charmingly tripped out.

“I have no problem with ‘Into Your Arms.’ My friend Robyn St. Clare wrote that song, and it was a great song,” Dando told Songfacts. “But ‘Mrs. Robinson,’ I never liked it, but I think it made good recently when it was in The Wolf of Wall Street, because I thought, ‘If it's in a Scorsese movie, it's finally making good for me. I'm OK with it.’ But for the longest time, I couldn't believe we did it, and a lot of our fans were disappointed that we put that out. They thought we were better than that, that we were kind of selling out.”

Like on “The Great Big No,” production on “Into Your Arms” is big and crisp and robust—a complete immersion in your headphones. In the ‘60s, the four-piece Robb Brothers (Bruce, Joe, Craig, and Dee) had been the house band on the variety show Where The Action Is, hosted by Dick Clark. In ’72, they decided to focus more on production, opening Cherokee Studios in Hollywood where they worked on a plethora of fantastic albums, including David Bowie’s Station To Station (1976), Steely Dan’s Pretzel Logic (1974), Michael Jackson’s Off The Wall (1979), and Warren Zevon’s final album The Wind (2003).

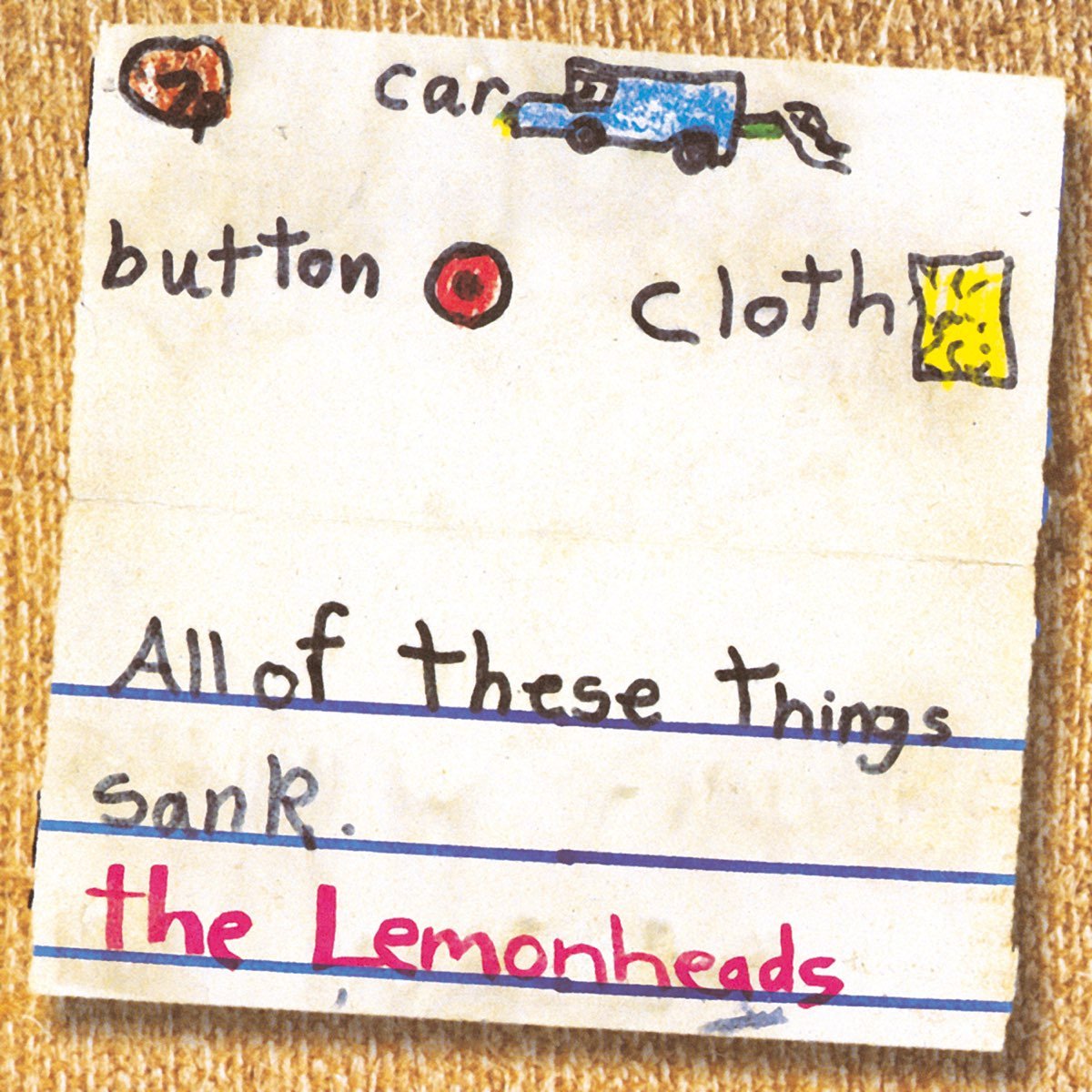

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about The Lemonheads:

The next song, the ballad “It’s About Time,” featured “written for Juliana Hatfield” in the liner notes, which added fuel to an already raging fire as to whether or not Dando and Hatfield were dating. At some point in the Hatfield-Dando ’90s news cycle, it came out that Hatfield was still a virgin, and so the obvious (but likely wrong) conclusion many fans came to is that the song means “it’s about time we fucked.” Nevertheless, it’s a beautiful ballad, featuring gorgeous harmonies with none other than Hatfield herself, and a very memorable lyric: “Have your people contact mine / And keep your lawyer on the line.”

The hyper, careening-yet-melancholy “Down About It” is one of my favorite Lemonheads songs —one I’d often listen to on repeat. “She’s gonna give me all the time I need / To finish it and if I can’t I’ll sleep… over.” It’s the kind of introspective yet crazy catchy Lemonheads song that made Dando a heartthrob—you can hear how bummed out he is about the relationship strife he’s experiencing, and he’s trying to own his part.

The jangly “Paid to Smile”—which, sonically, could have just as easily appeared on Ray as on Come On Feel—is about fame’s seamy underbelly, and the ickiness that comes with being objectified. Meanwhile, the countrified “Big Gay Heart” was inspired by an art collector Dando knew who had a bunch of gay art on his walls. “We called it ‘the big gay house,’ and it just sort of went on from there: ‘Big Gay Heart,’ like anti-gay bashing,” he recalled. “It was a combination of a comedy song and some political activism. It was a bit wacky, that song, and it caused a lot of people to wonder.” The video features a cameo by Chloe Sevigny and depicts a dance where everyone shares same-sex kisses at the end.

“Style” is a suspenseful, chugging noise-pop anthem whereby Dando provides this rather tragic thesis statement: “Don’t want to get stoned / But I don’t want to not get stoned.” Next up, the pop-punk, percussive “Rest Assured” gives us some of that antsy ennui the Lemonheads perfected on Ray. Dando goes to visit a girl, offering up some half-assed excuse as to why he’s there, and then they sit awkwardly around a leaf-filled swimming pool wondering what they’re both doing there. The following “Dawn Can’t Decide” furthers the sexy slackerdom—“Dawn can’t decide / If there should be more of the porch, she’s sick of being inside / He read the signs / Now they’re making out in Lancaster, just to pass the time (woo!)”

Next, enter the fabulous Belinda Carlisle on backing vocals for “I’ll Do It Anyway,” though this track is one of my least favorites due to its repetitive nature and its twangy Dando vocals. It does, however, feature a great final lyric to complement the song’s gallop: “I’m still a girl / And it’s just a horse / And I got the reins.” The next track, “Rick James Style,” is a slower, moodier, funkier take on the earlier track “Style” and features, you guessed it…Rick James.

The album takes a playful turn on “Being Around,” where Dando sweetly declares his desire to be in a young woman’s life, while questioning her desire for him—“If I was your body / Would you still wear clothes? / If I was a booger / Would you blow your nose?” Meanwhile, “Favorite T” mournfully boasts the keeping of someone’s favorite T-shirt after a breakup. The next-to-last track “You Can Take It With You” is a song about wandering around, whacking your way through some brush, and pitching a tent for some time to think. Finally, “The Jello Fund” was named after money Dando earned doing a TV commercial for Jell-O as a child, and it’s a 15-minute chaotic piano ballad that’s replaced by a hair-metal rocker about a guy named Lenny, and then replaced again by random noise.

After Dando’s throat healed from its crack ravaging, Adrian Deevoy, the Q journalist who interviewed him at the Chateau Marmont, caught up with him at the Reading Festival when he could finally speak and no longer needed to scrawl everything on a yellow legal pad. He was off the drugs, still a bit chastened by his ordeal, and was determined to not think like a people pleaser. “I felt so much pressure about the record. It was like, ‘Oh wow, I've got to do a record that everyone's going to really love,’” Dando reflected. “When I quit the drugs, I realized that all I had to do was make a record that I really, like, loved and that's its own reward.”

Flash forward to decades later, and Dando told the New York Times in 2019 that he’s still not clean and sober, called himself “a wicked manic-depressive,” and had just finished his first album in 10 years. And while he admitted that drugs don’t really do what you want them to do, his philosophy was that he probably won’t stop. “I’m sort of a fan of drugs and music. I think they’re good together,” he said. “I’m just going to be honest about it. Why lie?”

Listen: