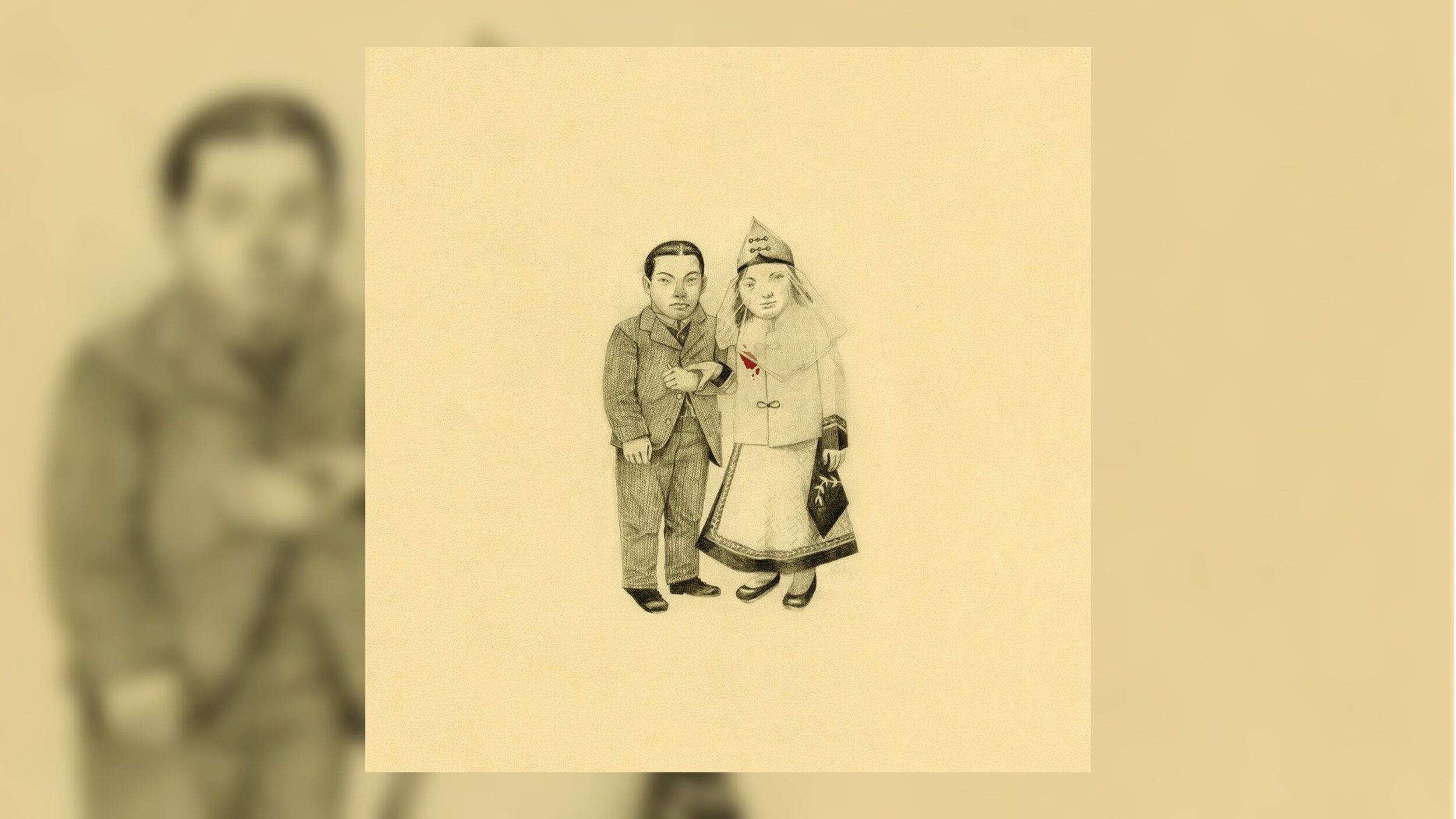

Happy 15th Anniversary to The Decemberists’ fourth studio album The Crane Wife, originally released October 3, 2006.

When I think of The Decemberists, I think of excess. They’re a band that goes all-out. There’s the board game, the audience participation in the song about being swallowed by a whale, the entirety of The Hazards of Love (2009)…all of this reveals a band that revels in excessive obscurities and oddities.

The Crane Wife (2006) is no exception. It’s a record with two multiparty odysseys, one of which (“The Crane Wife”) is a retelling of a Japanese folk tale, and the other (“The Island”) is a highly strange rendering of Shakespeare’s The Tempest. But, on no other album does the Decemberists’ decadent rendering of the bizarre lead to such a cohesive work.

Let’s start with “The Island.” My personal favorite part of the track’s twelve minutes comes during the second movement, “The Landlord’s Daughter,” which establishes Colin Meloy singing “ah ha!” in his falsetto early on. The first two times it happens, it’s nice—but the third time around, the band doubles the sixteenth-note theme and modulates up a fourth – no small potatoes—sending those two notes preposterously high up in Meloy’s voice.

High drama unfolds: It sounds like he’s been shot out of a cannon. As his arc begins its downward trajectory, the band hops back in with its manic theme, and we’re back at the races, instrumentally completing the hostage drama that was playing out in the lyrics. Moments later, we wrap up the movement and are jettisoned “You’ll Not Feel The Drowning” in which an unknown, emotionally detached murderer submerges a victim. This is the kind of tension and drama that their narrative and instrumental excess can give us.

Throughout the rest of the album, the band introduces us to a slew of other fantastic evils, keeping our attention with musical settings built-to-suit. Form follows function on ghost story after ghost story, sometimes set to driving alt-rock (“O Valencia!”) and sometimes to macabre baroque pop (“Shankill Butchers.”) A combination of whimsy and dread holds the whole thing together.

But the other great story of aesthetic on this album is the last two tracks. Unlike “The Island,” “The Crane Wife” has very little going on—we have the band’s regular live instrumentation, with some string backing. The comparative simplicity of “The Crane Wife” gives it a sense of knowability—with a simple story, this is a song that we can actually be a part of, rather than gaze at in wonder and fear. The tale itself—about a man who nurses a crane back to life, who then becomes his wife and weaves him beautiful clothes to sell and eventually leaves him when he becomes too greedy—is seemingly a cautionary tale against allowing our vulnerabilities getting in the way of our goodness.

Because the lyrics are a riff on a folktale, it is almost an obligation to create something that can be inhabited by the listener. And so, an ostentatious record, with this epic reading of Shakespeare, hopes to bring the listener inward on its title song through both lyrics and instrumentation.

Then, the masterstroke: we conclude with “Sons & Daughters,” a hopeful, simply arranged, singable round that puts so much of the chaos that we saw elsewhere on this album behind us. With the collapsing governments, war, murderous gangs, and monsters that make up the rest of the album now far from our minds, “Sons & Daughters” feels triumphant—at last, we’ve found something that makes us feel whole. For the first time, people on The Crane Wife are coming together.

This is the moment that renders the whole intelligible. The Decemberists (at least this time) are not doing a bit. They render everything that is dark and scary in our world into inventive musical fairy tales and myths, but not for no reason. They wrap it all in this folk story that reminds us of our obligation to goodness, and then show us what can happen when we actually do good.

LISTEN: