Happy 40th Anniversary to The Cure’s fifth studio album The Top, originally released April 30, 1984.

Wild and wicked effusions spiral from the psychoactive mind, and with a deranged half-laugh, half-howl, we’re off and spinning into the psychedelic storybook world of The Cure’s fifth album, The Top.

Slinking in the shadows of The Cure’s first trilogy—Seventeen Seconds (1980), Faith (1981) and Pornography (1982) —and pushing past the batch of innocuous synthpop singles called Japanese Whispers (1983), The Top (1984) emits a kaleidoscopic energy.

Although it bears certain musical hallmarks and lyrical themes of what came before, The Top illuminates the English rock group during a singular period in their 48-year history. It was a chaotic, uncertain time, with both the current identity and future existence of The Cure being called into question—not just by the media and fans, but by the band’s co-founder and frontman Robert Smith himself.

And so, in many ways, The Top is the closest we’ve ever come to a solo album from Smith (rumors are, he has at least one other solo album circa this time frame, but it’s yet to see the light of day…fingers crossed!). The intensity of “Fourteen Explicit Moments,” the tour touting Pornography, The Cure’s fourth album, had cast a dark spell on the longtime friendship of Smith and bassist Simon Gallup, leading to Gallup’s unfortunate, seemingly permanent separation from The Cure.

With the bonds among core members torn asunder, The Cure unofficially disbanded and went on hiatus. In Ten Imaginary Years, the account of the band’s first decade, Smith remembers, “I didn’t really feel the need to phone him [Gallup] up and say ‘You’re not in the group’—it would have been a pointless call because I had no intention of playing again at all. I was just fed up and, effectively, at that point, The Cure had stopped.” Accordingly, Smith disappeared, hiding in Welsh campground seclusion with girlfriend Mary Poole, while drummer Lol Tolhurst holidayed in Spain and France.

But although the fire may diminish, it never truly dies in the heart of the artist. Smith crept back into the studio by himself at first, then with Tolhurst to begin work on Japanese Whispers. And, despite various setbacks he was having with the band’s lineup, from late 1982 to 1984, Smith was amazingly prolific (overcompensating, perhaps, for his time away from The Cure). He participated in several collaborations, including touring and recording with Siouxsie and the Banshees, a side project with Banshee bassist Steve Severin called The Glove and a one-off single with film director Tim Pope.

Japanese Whispers had been a commercial success (it was the first album to enter the U.S. Billboard charts), but Smith had only agreed to do it as a favor of sorts to band manager and Fiction Records founder, Chris Parry. As evidenced by “this punishing regime” (as the liner notes for the The Top remaster describe his insanely demanding schedule), Smith remained conflicted about how to spend his time and ended up doing it all, by some miracle. At night, he’d sacrifice slumber, exploring what The Cure’s new aesthetic could be. And, by day, he still carried out full-time guitarist duties for Siouxsie and the Banshees, recording Hyæna (1984).

Listen to the Album:

Perpetually sleep-deprived, and frequently under the influence of mushroom tea, Smith still managed to compose the majority of The Top’s ten eclectic tracks singlehandedly. Each one offers a revealing glimpse into Smith’s mid-20s mindset. Clearly testing himself as an artist, he experimented with eccentric new sounds and arrangements—and even worked on bringing more variation to his singing (apparently, perfection knows no limits).

In addition to writing most of the songs for The Top, Smith also played most of the instruments. Beyond his customary guitar, he made entrancing use of violin, bass, keyboards, recorder and harmonica, fashioning seemingly errant sounds into luxuriously trippy tapestries. Meanwhile, Andy Anderson (who drummed on Japanese Whispers and The Glove’s album Blue Sunshine) lent his refined percussive abilities to the surreal soundscape.

At times, The Top echoes the despair of the early ‘80s trilogy, but it also transports us into a hallucinatory half-dream, where distinctions between consciousness, the subconscious and altered states irrevocably blur. Various settings flit across The Top, and in each, there’s a palpable feeling that everything is amiss. We’re baited into a psychedelic circus, and it’s clear the menagerie has cracked wide open. From dogs to birds to cats to pigs to bananafish, a variety of creatures—some real, some imagined—nightmarishly parade across the landscape of The Top. It’s a world where mind and flesh are careening out of control.

The record demands attention from the start with the roiling, danceable wonder, “Shake Dog Shake.” A rumbling drumroll quickly gives way to a manic cackle, with Smith soon extending an impish invitation, “Follow me to where the real fun is.” The impassioned song paints a squalid tale of loathing and regret—not far from Pornography in terms of mood. But, in spite of its caustic contents (with lyrics referencing spitting, spurning and shaking), Smith is right: there is fun to be had. As an album opener, “Shake Dog Shake” is deliciously vampiric, beckoning us into an unknown realm with just the right level of dare.

Reviving the heart with poetic fancy, the intoxicating “Birdmad Girl” delivers us from the preceding subversion. Perhaps inspired by Dylan Thomas’ “Love in the Asylum,” “Birdmad Girl” is Smith’s cryptically eloquent response. Employing stunning wordplay and impressionistic lyrics to illustrate a secretive correspondence, the sweetly catchy tune is somehow equally wistfully romantic and amusingly absurd, offering the enigmatic refrain, “Oh I should feel like a polar bear / It’s impossible.” It’s worth mentioning that Smith refers back to this birdmad girl 10 years later in “Burn,” a song he wrote for Alex Proyas’ cult classic, The Crow.

The mood of “Wailing Wall” differs from other songs on The Top, but shares a similar sense of emptiness, recalling the religious skepticism first deeply pondered in The Cure’s third album, Faith. Smith penned the lyrics for “Wailing Wall” while accompanying Siouxsie and the Banshees to Jerusalem. He depicts a dreary, greedy picture of spiritual devotion. The pilgrimage of the masses to the promised land is wrought with pain. And when he finally reaches the holy site, he finds anything but salvation.

As we delve into the core of The Top, the desperation radically begins to overtake Smith. The false sense of calm afforded by the slower-tempo “Birdmad Girl” and “Wailing Wall” is instantly defused and eradicated with the terrifying sensory assault “Give Me It” unleashes. Thrusting headlong again into Pornography-era turbulence, the song is a claustrophobic, hysteria-fueled frenzy of manic screams and jolts.

Frenzied saxophone, courtesy of co-founding Cure member, Porl Thompson, features prominently here, underscoring Smith’s thrashing journey from fight to despair. He yells with utter revulsion (“Get away from me / Get your fingers out of my face”) before suffocating in fear (“I’m gasping for air / I’m gasping for love”) and ends the song with dead-eyed surrender (“Deaden my glassy mind / Give me it / Give me it / Make me blind / One step back and one step down / And slip the needles in my side”). Six years after the album’s release, Smith reflected, “oh dear…I was not very good company around this particular song.”

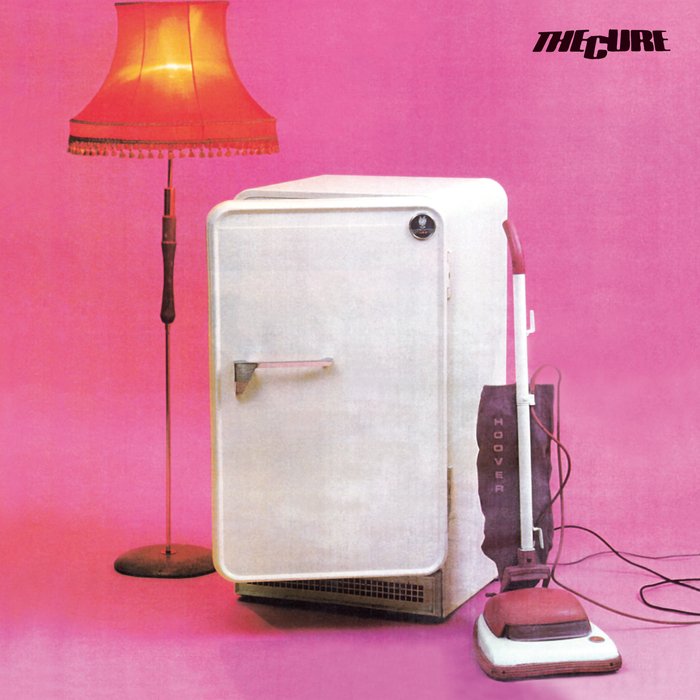

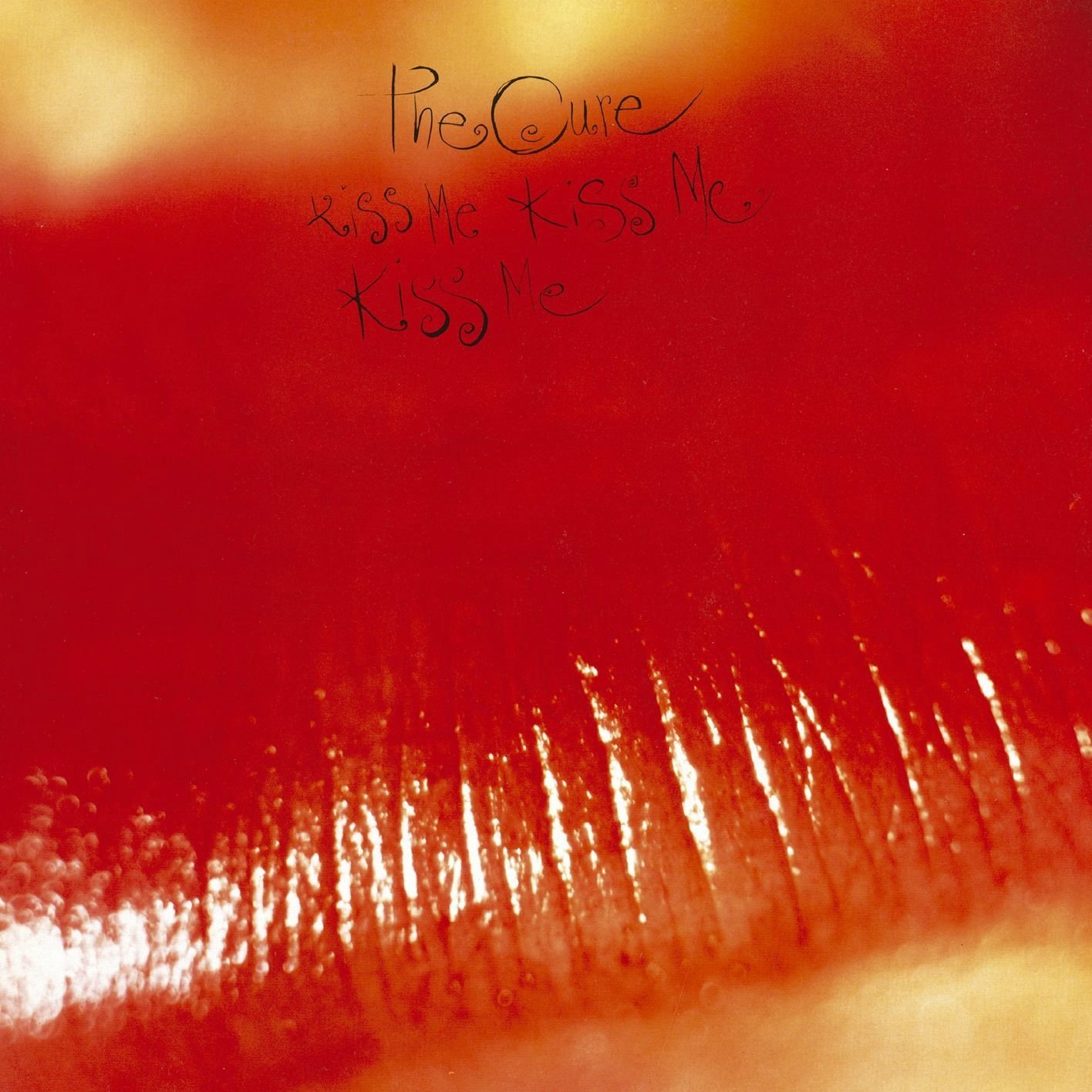

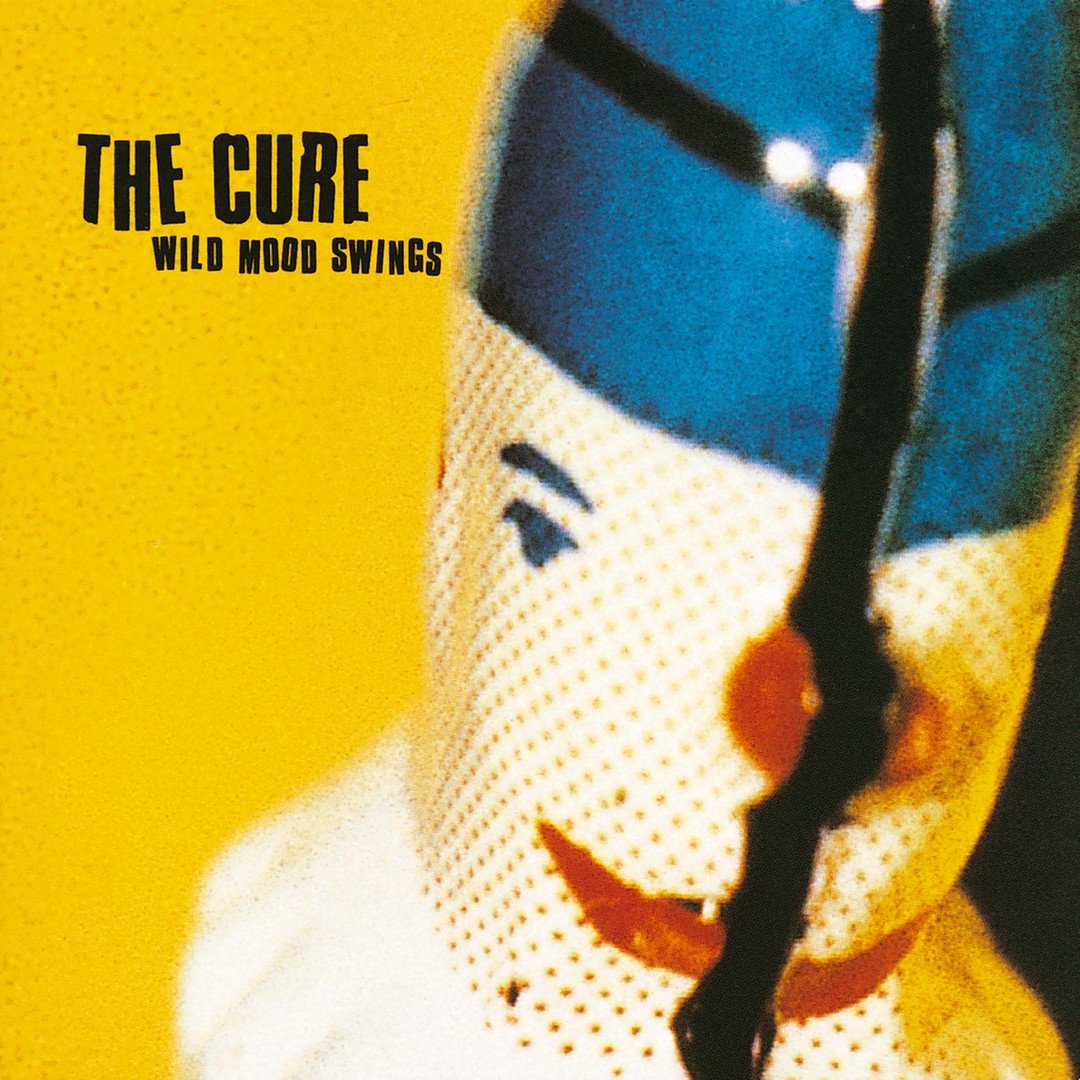

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about The Cure:

The woozy, whimsical “Dressing Up” follows the blistering panic attack. Though just under three minutes, it manages to slow down the chaos—a delightful comedown after the convulsive cacophony. Smith’s vocals are more playful here, too, sounding heavier, almost slurred as if he’s operating in a hypnagogic state.

“Dressing Up” also sets the stage for the album’s only single, “The Caterpillar,” which is the kind of fantastical pop gem that only The Cure can write. Beyond the romantic lyrics that tell of an endearing, but fleeting relationship, the song is notable for Anderson’s unexpected percussive flourishes and Smith’s lighthearted, onomatopoetic vocal delivery (“Flick-a flick-a flick-a… / Here you are! / Cat-a cat-a cat-a… / Caterpillar girl! / Flowing in / And filling up my hopeless heart / Oh never never go”). Without being too literal (thankfully), “The Caterpillar” expertly evokes the fluttering butterflies we all feel when falling in love.

The seventh song on The Top is my perennial album favorite. I remember being completely enchanted upon hearing “Piggy in the Mirror” for the first time 25 years ago, and I still adore everything about it. Smith has stated that the lyrics were inspired by Nic Roeg’s film Bad Timing and described the song as an expression of self-hatred, purportedly in a similar vein as “Shake Dog Shake” and “Give Me It.” And certainly the song seems like a bad trip, as though he’s caught in a prison of his own making (“I’m trapped in my face and I’m changing too much / I can’t climb out the way I fell in”).

But, “Piggy in the Mirror” also affords earnest, if ephemeral, moments of hope. Whether speaking to the partially recognizable face before him (the piggy in the mirror) or some other entity (who can really say whom?) I’ve always thought the line “Jump with me / for that old forgotten dance” suggests a desire for connection. Ultimately though, the song ends with a haunting acknowledgement of fugue-like disassociation, as though he’s caught, in limbo, between different worlds.

This theme continues in “The Empty World.” Alluding to Charlotte Sometimes, the Penelope Farmer novel that inspired The Cure’s 1981 single of the same name and the “Charlotte Sometimes” B-side, “Splintered in Her Head,” “The Empty World” also seems to reference the “Birdmad Girl” who uses her mind to escape reality: “She talked about the empty world / With eyes like poison birds / She talked about the armies / That marched inside her head.” Whether looking to flee unwelcome feelings through drugs or letting the mind cope by creating its own altered reality (perhaps even realities), the main narratives coursing through The Top are two sides of the same escapist hunger.

Ever intrigued by cinema and literature, Smith’s reading of J.D. Salinger’s “A Perfect Day for Bananafish” from Nine Stories led to the lyrics for “Bananafishbones,” the album’s penultimate track. The song puts a perplexingly whimsical spin on the alienation that pervades the tragic short story. It captures the same idea of broken communication, but from a more nihilistic stance. Additionally, like “Shake Dog Shake” (“Follow me to where the real fun is”) and “Piggy in the Mirror” (“Jump with me / For that old forgotten dance”), “Bananafishbones” offers more mischievous allurement: “Oh, turn off the lights / And tell me about the games you play...”

After one hell of a bizarre adventure (it’s hard to believe The Top is only 41 minutes long), we arrive at the “place where nobody goes…you just imagine it all.” In an album borne of psychedelic play and filled with references to games and toys, the closing title track, “The Top,” feels like a horrific taunt—a childhood game of make-believe gone terribly wrong. And yet, it shows maturity on the part of Smith – an acceptance that despite all the work, vices and distractions, he can’t truly escape his mind. He can’t hide from his feelings and pretend not to care about The Cure—or anything else that matters. The truth is, he doesn’t want to remain in isolation. And so, he signs off the album with the words, “Please come back / All of you,” coyly foreshadowing the redevelopment of The Cure and the towering artistic and commercial success that was to come.

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2019 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.