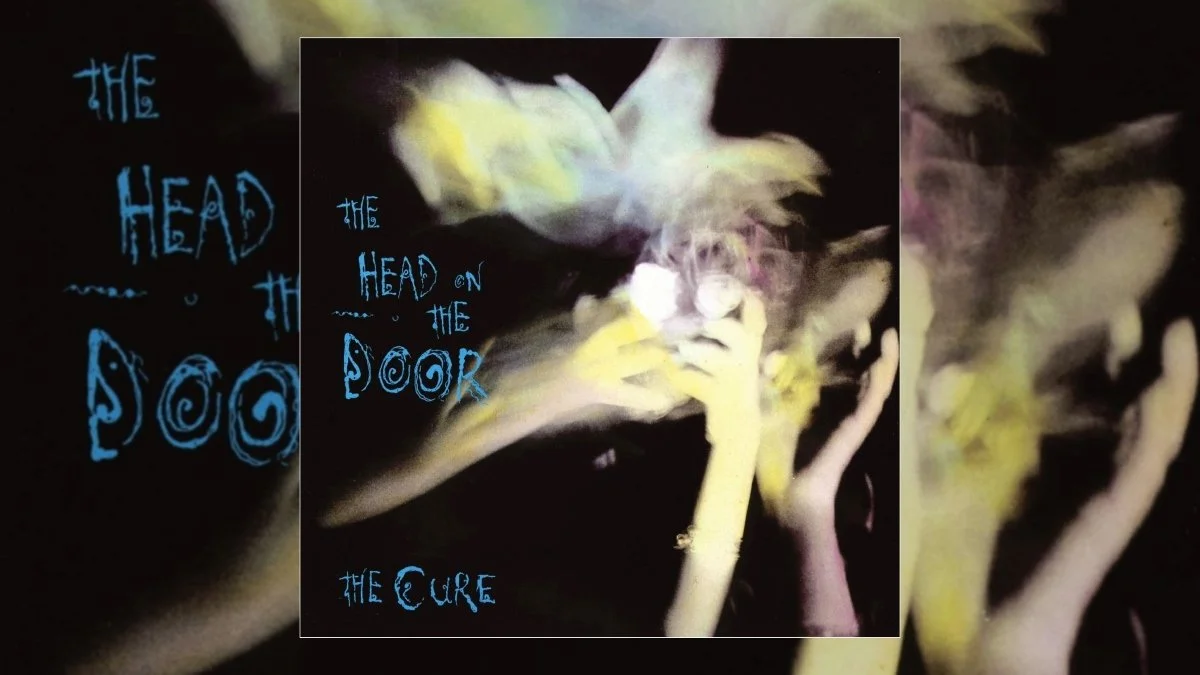

Happy 40th Anniversary to The Cure’s sixth studio album The Head on the Door, originally released August 26, 1985.

Bursting forth with Day-Glo faces, the reshuffled Cure that emerged in 1985 might have seemed an aberration. Gone were the blood-smeared eyes and conscious cloak of minimalism. In their stead surged new electricity—a neon-tipped visage au courant for synthy times.

But, don’t let The Head on the Door fool you.

If you hadn’t heeded the signals, “In Between Days,” the first single from the band’s sixth studio album, may have glinted like an iridescent pop grin spurting out of endless darkness. Certainly, fans had come to associate The Cure with the grim aesthetics of the 1980–1982 trilogy (1980’s Seventeen Seconds, 1981’s Faith and 1982’s Pornography). However, the near implosion of The Cure capping off the Pornography tour led frontman Robert Smith to experiment on his own. Both his side project, The Glove, and Japanese Whispers, a compilation including singles “Let’s Go to Bed,” “The Walk” and “The Love Cats,” showed a more whimsical, if chemically induced, side to his artistry.

Then in 1984, spun with psychedelics, out whirled The Top, closing with Smith’s woeful plea, “Please come back / All of you....” Just five years following The Cure’s debut, the group had already undergone myriad lineup shifts and had whittled down to Smith and co-founder Lol Tolhurst.

After nearly undoing his mind and band, the 25-year-old Smith realized it was time to make amends. One by one, he restored old ties and released himself from destructive habits and biases. And so, The Head on the Door not only marked the return of old friends bassist Simon Gallup and guitarist Porl Thompson, but also the debut of the brilliant Boris Williams, who formerly drummed for Thompson Twins—and would go on to become the percussive force behind many acclaimed Cure albums, including Kiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me (1987), Disintegration (1989) and Wish (1992).

“I was having so much fun playing with a drummer who was so natural and imaginative. Boris, Porl and Simon clicked right away…It totally changed my idea of what The Cure could be,” Smith reflected in the liner notes of the Head on the Door reissue (2006).

Less than one year after the release of The Top, Smith saw his wish fulfilled. Not only was the band restored, but it was bigger and stronger than ever. In February 1985, the five-piece went to work together at London’s F2 and Fitz studios. Building on demos Smith had composed in his Maida Vale flat, the resurrected Cure evolved The Head on the Door album tracks and B-sides as a group. (Merely picturing this sends me aflutter. “A Few Hours After This,” you know you forever destroy me.)

A few weeks later, they were ready to record. Outfitted with toys, liquor bottles and a general air of merriment, the environment at Angel Studios was festive, with the band instantly finding a natural rhythm, meshing evening revelry with nightlong creativity.

Listen to the Album & Watch the Official Videos:

In Ten Imaginary Years, which vividly details the band’s first decade, Smith recounted, “We played pool a lot and had fun. The atmosphere was stupid, almost childish and we were in a hurry to get back in the studio every day. With Simon, the excitement came back and the band was more aggressive, more vital. He knew me so well that I didn’t really need to explain anything to him. We drank a lot more than at any other recording session, but this time we didn’t take any drugs.”

After 18 months apart, the reunion of kindred spirits Smith and Gallup repaired a fissure in the band’s sound and soul. Catalyzed by camaraderie, The Cure enjoyed a newfound sense of purpose and possibility. The songs blossomed with such ease, as Smith recalled in the reissue’s liner notes, they practically wrote themselves: “I had these three [keyboards] in my flat and every day I’d find a new sound, a new voice. Songs like ‘Close to Me’ and ‘Six Different Ways’ almost seemed to happen without me!” (Oh, please spare us the modesty, dear Robert. We all know none of it could’ve materialized without you.)

And, for once, artistic and commercial forces converged. With The Head on the Door, The Cure triumphantly delivered on Smith’s intention to make a “slightly skewed pop record,” at once summoning the burgeoning MTV-fueled alternative subculture and substantiating the budding phenomenon called new wave.

“I was trying to create a sort of attractive tension by marrying slightly bitter words to really sweet tunes,” remarked Smith.

The pull between the two imbues the record with provocative depth, which is magnificently brought to life in album opener “In Between Days.” Crashing in full tilt, with its irresistible drums, spine-tingling guitars and sparkling synth, the deliriously upbeat track is assuredly a dance-floor gem. And maybe, if you didn’t really know The Cure, you’d buy the fluorescent-faced proposition put before you. (Fittingly, the single charted highly in both the UK and US, and remains popular to this day.)

But, should you linger a little longer, a soft melancholy just might set in. In crisp contrast to that gleeful sound, the very first words of the album sing a different, more dismal, tune: “Yesterday I got so old / I felt like I could die / Yesterday I got so old / It made me want to cry.”

Despite being a radio-friendly hit, the song also subtly introduces the predominant theme of the album: fear. Specifically, our darkest demons from our earliest days (“Yesterday I got so scared / I shivered like a child”).

For as much as The Cure’s sixth studio album offers a window into a rejuvenated band at play, behind its youthful pop façade lurks a wicked tickle of fear (“a smile to hide the fear away”). Recalling puppet shows borne of feverish hallucinations, The Head on the Door peers back at that disembodied face hovering above Smith’s childhood doorway, beckoning us to confront our most primitive monsters.

While previous Cure albums largely examined the various agonies of the adult mind, The Head on the Door reaches back to those formative years. This is where it all began—where at some point the innocence of youth absconded and traded in its place a prevalent sense of doom.

Appropriately mixed up in this subterranean space are enigmatic effusions of the nightscape. Titled after the Japanese stringed instrument, the koto, and likely inspired by the ancient capital itself, “Kyoto Song” lulls us into a disorienting dream. With the narrator aswim in a smudgy state of consciousness, the sensual tune unfolds like the mind sifting between two sides—only we get the hazy sense that the so-called nightmare is more appealing than anything real.

Continuing in a similarly heady vein and dialing us halfway around the world is “The Blood,” a song Smith wrote under the influence of cheap Portuguese wine called The Tears Of Christ. Wrapped in flamenco flair, the lyrics are reminiscent of “Fire in Cairo” from The Cure’s debut Three Imaginary Boys (1979), heartily transmuting corporeal existence into fantasy and temptation.

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about The Cure:

Shifting tone and creating a pathway to the album’s darker second half, “Six Different Ways” is another beautiful example of the dulcet pairing with the caustic. Repurposing the piano Smith composed for single “Swimming Horses” during his stint with Siouxsie and the Banshees, the delicate, pretty, yet peculiar track has elicited much speculation over the years. With the line “Six sides to every lie I say / It’s that American voice again,” it might well be a reference to Smith’s amusingly mendacious demeanor when dealing with the press. But, I’m not convinced, especially since the words were written before The Cure began selling out stadiums in the US. My interpretation of “Six Different Ways” skews more introspective, suggesting conflicting—even disturbing—aspects of the psyche (for clues, cue next song).

All hail the visceral guitar glory that is “Push.” A perennial crowd-pleaser imparting all manner of exhilaration live, I pity the hapless soul that remains unmoved. I still remember the first time I saw the song performed live, on VHS tape, that is (and please, if you’ve never seen The Cure In Orange, do right this egregious wrong immediately). Only The Cure could make these cryptic lines (“Oh! smear this man across the walls / Like strawberries and cream / It’s the only way to be”) so gorgeously cathartic. And lest you believe the power of “Push” rests solely in its euphoric crescendo and accompanying release, I urge you to step closer.

Tucked into the center of The Head on the Door like a sleeping child fending off a sneering creature, “Push” harbors some of the album’s most sinister lines: “He gets inside to stare at her / The seeping mouth / The mouth that knows / The secret you / Always you / A smile to hide the fear away.” Throughout the album, there are hints of another: Something, or someone, is watching. As children, we’re all frightened by that creepy figure in the night (lord knows my older cousin had a direct line to the bogeyman). But, exponentially more terrifying is the adult realization that the menacing face staring is—and always was—you.

And well, is it any wonder the ensuing track is called “The Baby Screams?” Actually, in the context of the album, the song functions as an odd, but needed reprieve betwixt the heart-soaring rush of “Push” and the shimmying splendor of “Close to Me.” While admittedly my least favorite of the lot, “The Baby Screams” is intriguing in its singularity. In an album riddled with nocturnal illusion, this deviant yowls into the sunless ennui that typifies the waking hours.

Indeed, no one revels in the thrills of the night quite like The Cure. And as we prowl toward the album’s close, the evidence grows more and more telling.

Slipping again into that indistinct realm where fancy meets fear and the eyes of nightmares stare wide awake, “Close to Me” is my idea of pop perfection. It’s also how my greatest love affair of all time began, which is to say it’s the exquisite song that introduced me to The Cure. (Should anyone seek details, my nine-year-old self will gladly come tumbling back out to regale you with the memory.)

While clearly “Close to Me” was released to radio, as the album’s second single, so that I might meet my destiny, it’s also just undeniably catchy and fun. Pertly panting and eclipsing syllables, Smith’s vocals are at their most beguiling. Of course, like “In Between Days” and so much of the record, its jaunty verve veils its many doubts and demons.

If “Close to Me” tempted my strange childhood impulses, the next track tantalized my adolescent (and current, I’m not afraid to say) sense of rain-kissed romance. Enraptured at once by its stunning poetry and cinematic atmosphere, “A Night Like This” only grew in significance upon learning that it was my first major crush’s favorite. I’d whisper the words into the glistening darkness, wishing to be found. And although I’ve halted such behavior, I still pine for the feeling.

The penultimate song, “Screw,” is the briefest and also the weirdest on The Head on the Door. Perhaps the slightly older sibling of “Piggy in the Mirror” (The Top), the twisted tune unfolds like a bizarre looking-glass conversation. As a setup for what follows, there is recognition here, as with “A Night Like This,” of a desire to change.

“Sinking” is the inevitable conclusion to an album that trips back in time to the emergence of the psychological shadow (“The secrets I hide / Twist me inside / They make me weaker”). With all flashes of juvenile ebullience—even in the dazzle of their delusion—now a distant memory, this is the moment of reckoning. Where “In Between Days,” in its giddy stupor, turns reality on its head (“Yesterday I got so old”), “Sinking” surrenders to the present truth (“I am slowing down / As the years go by / I am sinking”).

Whether escaping via dream, fantasy or vice, there was drama in these other worlds. As The Head on the Door closes and the sheen of younger days fades, the terror now dwells in the emptiness that comes from the dulling of emotion (“I crouch in fear and wait / I’ll never feel again…”).

The funny thing is when I consider the albums that followed, I can’t help but shiver like a child. So, on my tiptoes, I’ll stand and await the kiss…

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2020 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.