Happy 50th Anniversary to Terry Callier’s What Color Is Love, originally released in August 1972.

Terry Callier’s story is such a heartwarming and positive one, that in these dark, cynical times it makes you regret his untimely passing in 2012, aged just 67, even more. Born on the north side of Chicago and raised in the Cabrini-Green housing projects, he was childhood friends with Curtis Mayfield and Jerry Butler, and began his musical life in the same way as they had—doo-wop harmonizing in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

His path though would divert to a more folk and jazz influenced one, performing in coffee houses and soaking up Coltrane during his college years. A debut album appeared in 1968 on Prestige Records entitled The New Folk Sound of Terry Callier, but by the beginning of the 1970s, Callier found himself writing material for Chess Records subsidiary Cadet. Before long, he was recording solo material that revealed far more to his style than a straight-up folk sound. Jazz, soul and folk entwined effortlessly to produce three albums of unique charm for Cadet over a three-year span: 1972’s Occasional Rain and What Color Is Love, followed by 1974’s I Just Can’t Help Myself.

His recording career continued—albeit less successfully—through the ‘70s and early ‘80s until he abandoned music to take custody of his daughter and teach computer programming at university. Then some years later, the obscurity he’d sought out began to dissipate. With music too good to stay hidden, acid jazz DJs began to unearth the treasures in his past and play them to hungry, eager crowds who lapped up his unique brand of soulful sounds. It wasn’t too long before he returned to recording with the masterful Timepeace in 1998 and his latter day rejuvenation was complete—a return to what he loved that lasted until his passing in 2012.

It is the middle of the three Cadet releases that I mark, celebrate and generally extol the virtues of here. What Color Is Love is 40 or so minutes of undiluted bliss and beauty that deserves to be heralded in the same way as those titanic soul albums of the 1970s by artists such as Stevie Wonder, Donny Hathaway and his childhood friend Curtis Mayfield.

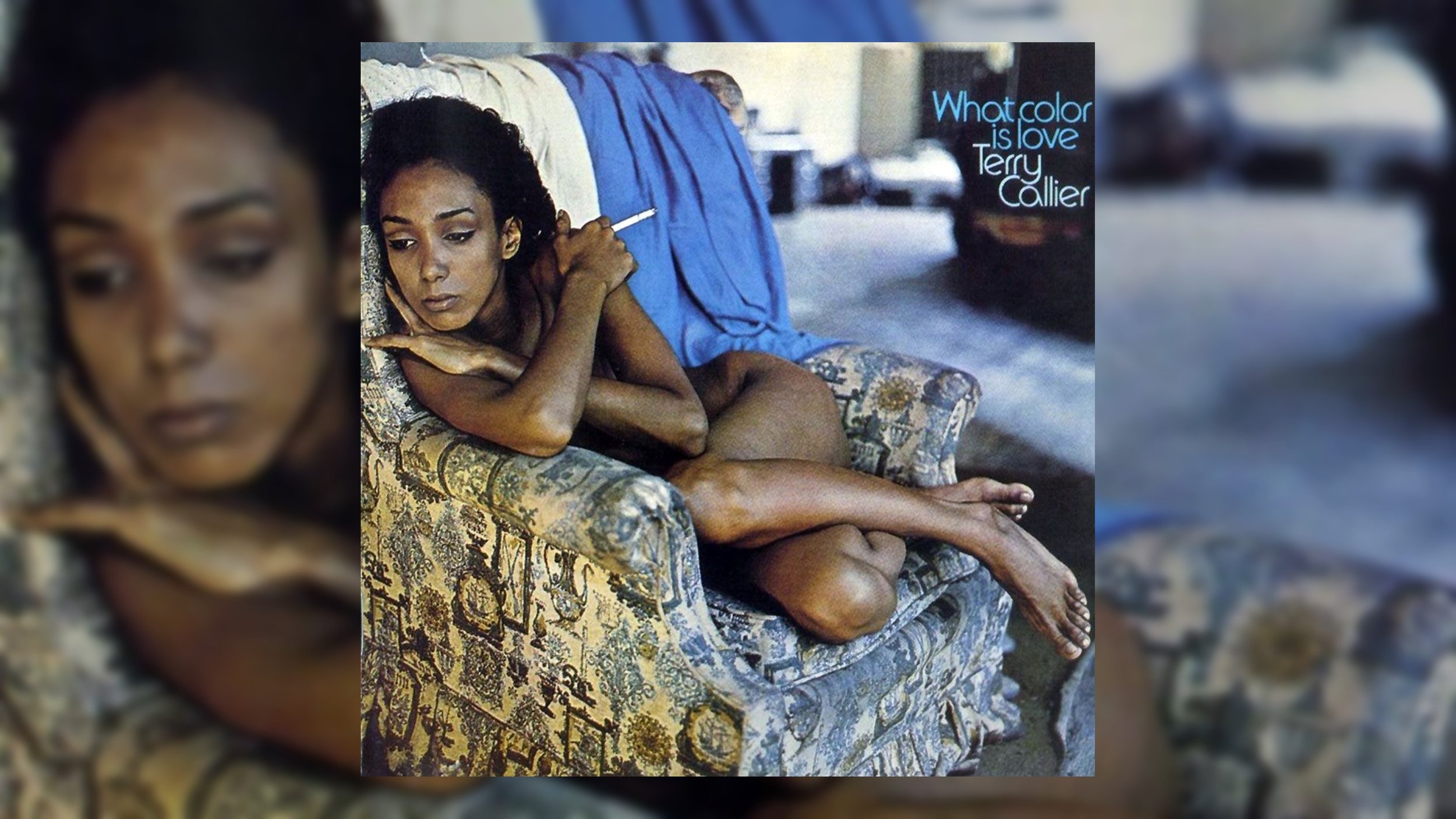

The album cover is revealing in more ways than the obvious one. A naked, huddled black woman sits curled up on a faded armchair with an un-smoked cigarette burning dangerously long, while staring into the middle distance, deep in somber thought. This is an album of similar beauty as the figure featured, and across its seven songs, it has the same ruminative disposition that is etched on her face. It is lightly tinged with dismay at the state of the world but ultimately places its hope on love being the redeeming feature of the world.

Listen to the Album:

Listening now in these sometimes wretchedly dismal times, it is easy to look upon its occasionally straightforward lyricism as “twee” or some such, but that is to miss the heartfelt directness of the lyrics. It also sums up Callier’s approach to music—there’s no concession to trying to be cool, just a desire for universally accepted self-expression and positivity.

Though Larry Wade and Jerry Butler both crop up on co-writing duties, the standout collaboration is with Charles Stepney on production duties. Fresh from his work with Rotary Connection, Minnie Riperton and Howlin’ Wolf (to mention just three of many), he lends proceedings a lushly dramatic tone, amplifying the personal songs with sweeping arrangements to produce an album of sheer delight.

Album opener “Dancing Girl” is a 9-minute long astral plane venturing fan favorite that transmogrifies from a delicate paean to an unnamed beauty to an urgent Gil-Scott Heron like plaintive wail of anguish at the fate that awaited the object of his affection. Screeching horns, subtle strings and Callier’s straining, desperate vocals peak magnificently in the closing three minutes, before descending once more to the dream like state of the opening.

Title track “What Color Is Love” is a simple musing on the nature of love: “Does it glow like an ember / And do you remember / If love doesn’t last / Does it live in the past.” The soaring strings of Stepney’s production and the splashes of cymbal that punctuate its progress lift the song on wings to greater heights.

Central to the album’s genius is the third song on the album, “You Goin’ Miss Your Candyman.” With a phenomenal bass line that was sampled for Urban Species’ “Listen” in 1994, it marks a rare venture into the carnal side of love in Callier’s discography. More commonly invested in romantic notions of love, Callier finds his inner alpha male and at the zenith of the song, a lupine howl of desire issues forth from the depths of his desire, as a torrent of longing, fragility and passion.

Having sullied his mind with the carnality of “Candyman,” he returns to his usual mode d’emploi with “Just As Long As We’re In Love,” a swooning love song of impeccable credentials: “And there’s so many things I wanna say / But words alone won’t ease your mind / Sometimes I wish we could fly away / Leave this all behind.” Once again Stepney’s production takes the song and infuses it with more drama courtesy of the string and percussive flurries.

“Ho Tsing Mee (A Song of the Sun)” shares the same common man’s touch of disbelief at the state of the world that Bill Withers had: “Here is the ending / Children dying in their daddy’s war / Heroes who’ve been there/ Say they never wanna fight no more.” Callier then questions God’s capacity in a world so terrible: “But with so many souls to keep / And a universe so deep / Can it be you just don’t hear us / When we weep.”

If ever a song summed up Callier’s life choices and style, it is penultimate track “I’d Rather Be With You” with its opening lines: “I could take my guitar /And hit the road, try to be a star / That sort of thing / Just don’t appeal to me.” Such a simply delivered song packs a mighty punch due to Callier’s warm and mellifluous intonation.

And that is what has been studiously missing so far here: an ode to Terry Callier’s comforting voice. In the same way that Morgan Freeman’s voice plucks our hearts strings so effectively, so Callier possesses the same integrity, emotional security and gravitas to peel away layers of cynicism and penetrate the listener to their core, connecting with every lyric, every stanza and every verse.

All of which makes it ironic that the final song on this hidden gem doesn’t feature his voice at all. Ostensibly an instrumental track showing off the melodic touch of Callier and Wade and the production prowess of Charles Stepney, it imbues a permanent state of bliss for its duration.

Having had the pleasure of seeing Callier perform live a number of times, what became clear to me was the esteem he was held in by his fans. Sure, every concert was packed with rabidly ardent fans, but there was definite reverence in the air each and every time I was lucky enough to see him take the stage. Such emotional heft could only come from a generous soul with a divine connection to his fans—something this humble man had in abundance.

If you don’t know Terry Callier’s music, start here, in fact start anywhere. Just get some in your life.

As an Amazon affiliate partner, Albumism earns commissions from qualifying purchases.

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2017 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.