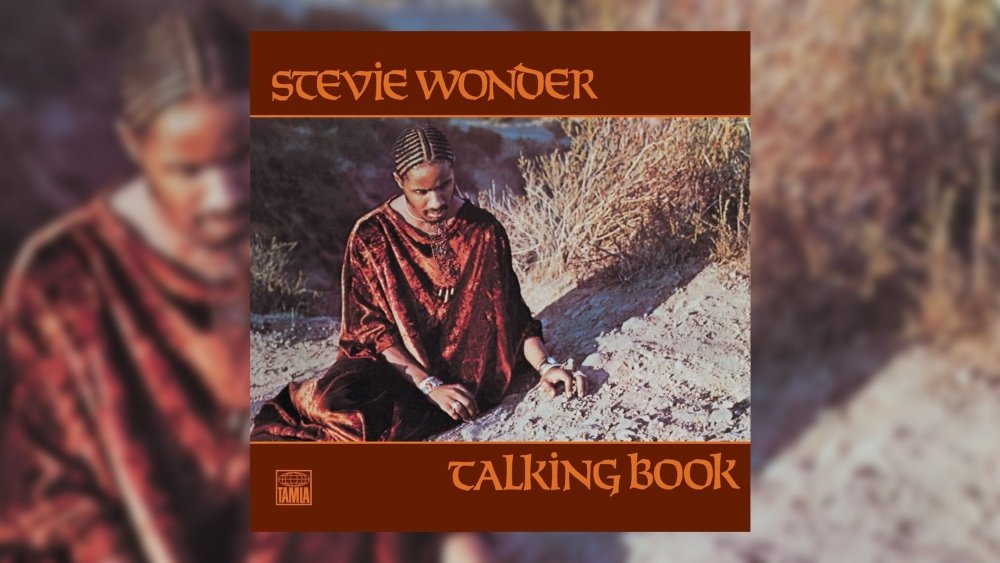

Happy 50th Anniversary to Stevie Wonder’s fifteenth studio album Talking Book, originally released October 28, 1972.

My name is Patrick and I am an idiot.

To anyone reading this who knows me personally, this is hardly breaking news. But to those who only know me via Albumism, I’m hoping this comes as a surprise (if only a slight one).

Before I reveal the reason for this spontaneous outpouring of self-flagellation, I’d like to offer some form of justification for my stupidity. In my defense, I was young—naïve to the ways of the world and the glories of songs unknown. I grew up in the UK during the 1980s with 3 television channels, meaning Top of the Pops was the only place to see videos and hear music on TV, whilst BBC Radio 1 dominated the airwaves in all its monolithic iconography.

Which means when Stevie Wonder hit number 1 in 1984 when I was nine years old with “I Just Called To Say I Love You”, that was the extent of my knowledge of Stevland Hardaway Judkins’ catalogue and, frankly, to my ears it sucked. Hard. In fact I found it toe-curlingly, embarrassingly cheesy (and still do to this day) and it made me never want to hear any more of his music.

See? I told you I was stupid. (Don’t worry, there’s a twelve-step program for it.)

Fast forward approximately 13 years and I’m in an ex-girlfriend’s house flipping through her mother’s impressive vinyl collection. As a veteran of the California Ballroom in Dunstable (a town some 20 miles from the northern edge of London), she’d seen many of the classic soul groups of the ‘60s and ‘70s bring their moves to town and owned the vinyl to prove it.

Rifling through in awe and excitement, it wasn’t long until my perceptions were shattered. There, adorned in dashiki, without his trademark sunglasses and hitherto ever-present million-dollar smile was Stevie Wonder staring somewhat enigmatically into the middle distance—the exact opposite of cheesy.

Intrigued and inspired, I flipped the vinyl to read the track listing and immediately my brain was flooded with half remembered titles and tunes, things I’d picked up without really knowing about it. With a fair amount of trepidation I removed the vinyl from its sleeve and placed it on the turntable. I waited for the needle drop.

What I heard blew my mind and sent shame coursing through my veins simultaneously. How could I have been so stupid?

Listen to the Album:

In what ways though did this album reveal my buffoonery, to the point where I am now willing to publicly humiliate myself for your gratification? Why is the album such an important piece of musical history?

Released at the end of October 1972, it followed hot on the heels of Music of My Mind in establishing Wonder as a fully-fledged, grownup artist freer of the shackles that Motown’s winning formula had imposed on him and countless other legendary artists. It also found Stevie at the center of a maelstrom of personal and professional upheaval. Professionally he was constantly on the road (even finding time to pop up alongside John Lennon and Yoko Ono for a benefit gig at Madison Square Garden) and personally his marriage to Syreeta Wright was crumbling like a sandcastle at high tide.

That personal turmoil is the de facto theme of the album. Heartbreak seeps from its pores despite the main body being bookended by two characteristically euphoric Stevie Wonder songs. Jim Gilstrap’s rounded mellifluous tone makes “You Are the Sunshine of My Life” a perfect start, unashamedly romantic and more soothing than honey and lemon tea. Is there anyone else with the generosity of spirit to kick an album off with a backing singer’s voice?

Shorn of the modern curse of overstuffing albums, the 10 tracks here are all winners in one way or another, be it musically, lyrically or—most often—both. “Maybe Your Baby” is a case in point. The slow-grinding, down-low groove sneers, blinking through the tears of heartbreak whilst the lyrics hit like a sledgehammer: “Heart’s blazing like a five alarm fire / And I don’t even care . . . / I feel like I’m slipping / Slipping deeper into myself / And I can’t take it / This stuff is scarin’ me to death.”

The devastating simplicity of “You And I” allows his voice to soar and the note that he holds some 20 seconds from its conclusion sends shivers down the spine. The breezy tale of longing that is “Tuesday Heartbreak” and the slinky insinuation of “You’ve Got It Bad Girl” offer further proof of a man capable of almost anything, but both (and indeed most other songs) pale in comparison with what comes next.

The epochal funk groove of “Superstition” is as staggering today as the first time you ever heard it. Once on the verge of being given to Jeff Beck to record, it found Stevie eager to show his Hohner model C clavinet as a dirty, nasty and funky machine. Consider the world well and truly shown, Mr. Wonder.

A musician can tell you more about the pentatonic run that makes up the riff, but (like all funk) it’s the gaps in between the notes where the deepest funk resides. If you aren’t moving within four seconds of it starting, then you’re either dead or stupid. Just be grateful that one of these realities has a twelve-step program.

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about Stevie Wonder:

The contrast between the jolly musical core and lyrics of “Big Brother” couldn’t be greater as he rips into politicians in a way he would rarely repeat and offers hitherto unmatched social commentary: “My name is secluded / We live in a house the size of a matchbox / Roaches live with us wall to wall.” And the final scarily prophetic words are more relevant now than ever: “You’ve killed all our leaders / I don’t even have to do nothin’ to you / You’ve caused your own country to fall.”

The album rounds out with the lovelorn “Blame It On the Sun” and the Jeff Beck aided “Looking For Another Pure Love” both given a delightful lyrical touch by Syreeta Wright, before the final tour de force of “I Believe (When I Fall In Love It Will Be Forever)” that boasts opening lines of such depressing heft (“Shattered dreams, worthless years / Here am I encased inside a hollow shell / Life began, then was done / Now I stare into a cold and empty well”) that the euphoric ending of love found is as welcome a relief as you will ever hear.

But beyond the obvious compositional quality of the 10 songs therein, what the album also does is provide the groundbreaking soundtrack of the Moog synthesizer finding its feet in popular music. On Talking Book, Stevie Wonder established the synthesizer as the all-conquering tool it would become and alongside Robert Margouleff and Malcolm Cecil, he created a multi-layered sound of different textures that, despite their complexity, radiate warmth that embraces the listener in a veritable sheepskin hug.

Now all these years after my road to Damascus experience I have all the zealotry of a born-again Christian, always eager to proclaim Wonder’s greatness and worship at the rarely equaled run of albums that followed this in the rest of the 1970s.

And all I have left is to find the person responsible for my conversion and thank them profusely. Brenda, this one’s for you. Thank you.

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2017 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.