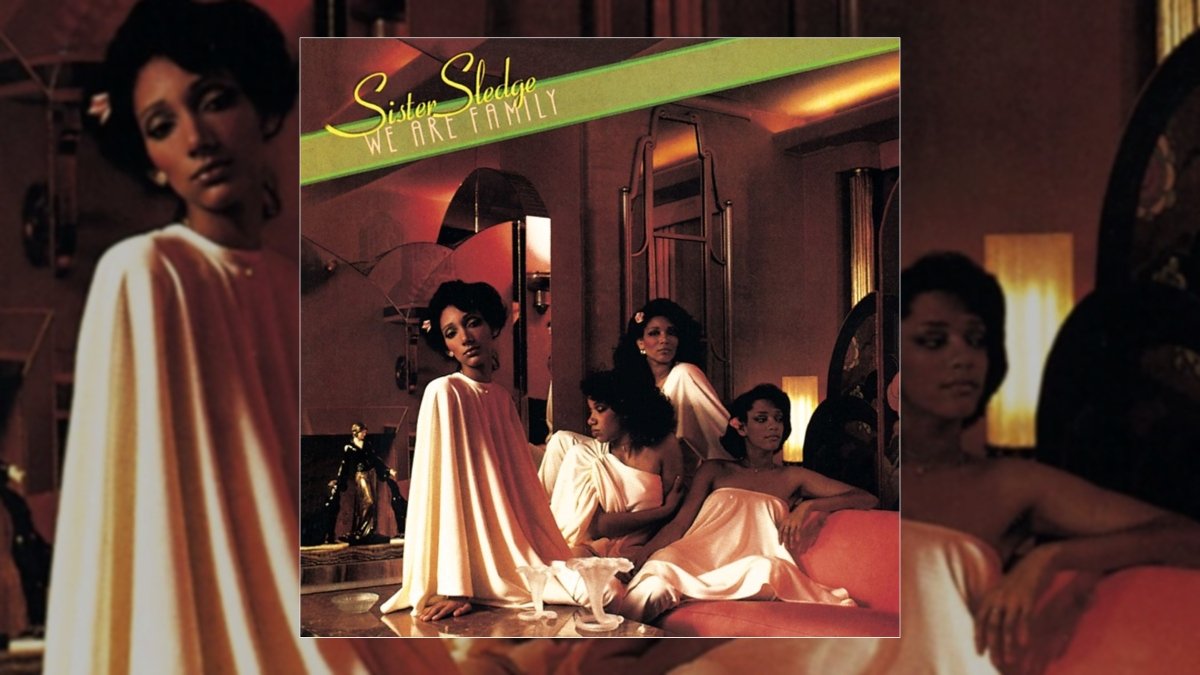

Happy 45th Anniversary to Sister Sledge’s third studio album We Are Family, originally released January 22, 1979.

By the summer of 1979, disco music had come a long way. What had started in underground private parties in the slowly decaying New York City of the early 1970s had become a commercial behemoth sweeping all before it. Birthed by Black and Latin members of the LGBTQI community, it found its white hetero male “figurehead” in John Travolta’s Tony Manero in 1977’s Saturday Night Fever. As all innovators find out though, all it takes is a white hetero man to ruin everything by alerting money-grabbing record companies to the profitability of a watered-down, reductive version of an art form stripped of its character and charm.

By 1979, some 200 radio stations had become entirely devoted to the four-to-the-floor beat and indefatigable hi-hats that had originated with Earl Young’s drumming on the iconic Sound Of Philadelphia recordings with Gamble and Huff. Their sweeping orchestrations and aforementioned drum patterns laid the foundations not just for a new iteration of soul music but also the nascent genre that would become known globally as disco. Across its journey to global hegemony, disco offered some Black women the opportunity to break glass ceilings and become stars who crossed over the still segregated chart system of the era. Gloria Gaynor, Labelle (formally Patti Labelle and the Bluebells), Thelma Houston and Candi Staton left behind solid if unspectacular careers to become the vocalists who represented disco and cross over to become household names, including white households.

For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction though, and white, middle American rock music was not going to surrender its dominance easily or without a fight. That language may seem hyperbolic or exaggerated, but what unfolded in the summer of 1979 more than justifies it. Chicago “shock-jock” Steve Dahl organized a mass destruction of disco records at Comiskey Park stadium (then the home of the White Sox) both as a publicity stunt and as a genuine hate-filled retort to disco’s immense popularity.

Thousands poured into the stadium on July 12, 1979, lured by Dahl’s antics and the dirt-cheap price of the tickets—in fact the stadium was over capacity by several thousand. In between the two games that were planned for that evening, a crate loaded with disco records was exploded and all hell broke loose. Thousands stormed the field and damaged it, resulting in the cancellation of the second game (which the White Sox forfeited) and rioting ensued.

Looking back 45 years later, the whole episode serves as an example of when you’re accustomed to privilege, equality will feel like oppression. An art form created by young gay, Black and Latin people surged to popularity and challenged the staid status quo and was beaten down by the response of that threatened group. It is impossible to ignore the racist, sexist and homophobic overtones of that wildly violent and incendiary response to an art form.

Sister Sledge’s We Are Family must have been among those records that were destroyed that fateful evening. Released in January 1979, it is hard to imagine what those responsible for destroying disco records found so offensive. Unless, of course, it was the irrepressible joy and impeccable musicianship contained within that made their eyes burn so brightly green.

Listen to the Album:

For the sisters though, it was somewhat of a last chance saloon. In an interview with Alexis Petridis for The Guardian in 2016, Joni Sledge revealed the frustration of eight solid but largely unremarkable years in the business, scoring minor hits and supporting acts who passed through Atlantic City. On the brink of leaving the business for something more stable, they were introduced to Nile Rogers and Bernard Edwards of Chic and decided to chance a final throw of the dice.

Despite the absolutely perfect harmony of voices, melodies and grooves, things were not exactly plain sailing. In the same interview with Petridis, Debbie Sledge explained the contrasts in working styles between the sisters and Rogers and Edwards. “We were used to coming into the studio prepared,” she explained. “And the way Chic worked was the opposite. They wouldn’t show us what they were doing because they said they wanted spontaneity…so it was fun, but frustrating.”

That frustration is impossible to detect across the eight tracks that make up We Are Family, as the combination of Chic’s trademark effortlessly smooth funk and the Sledge’s imperious vocals are a sublime match. The reason they work so well together is the understated yet powerful quality of both the music and the vocals. While some of the more generic and derivative disco tracks from others sound like a shopping cart laden with every cymbal, whistle and bell available being pushed down a set of concrete steps (crash, bang, wallop so to speak), that is definitely not the case here.

Chic’s arrangements give plenty of space for the instrumentation to breathe and at a slightly slower tempo than some. The hi-hat from Tony Thompson’s kit doesn’t sound as prominent or naggingly insistent as some others and the use of strings is always restrained and limited for great effect—like underlining or highlighting words in a document. And amidst it all are the vocals of the entire Sledge collective—resplendently luxurious at every turn. Chief among them is youngest sister Kathy, who demonstrates the sweetest tone with the merest hint of velvety growl lurking somewhere deep inside on the half of the album where she is on lead vocal duties. No matter who takes lead though, there is a distinctly unhurried approach to the delivery, despite the dancefloor pace of most songs. Vocals sail serenely over the musical ocean of Edwards and Rogers’ making.

I must confess at this point to not always having appreciated this album in the way I do now. The context in which I first heard the hits contained on the album had an impact on my enjoyment of it. Tired church halls with sticky floors and shabby birthday decorations combined with middle aged women dancing in circles at family gatherings did not appeal to a younger version of myself. The ignorant vehemence of youth led me to think in ways much too close for my liking, to those who meted out such destructive (false) judgement at Comiskey Park.

But with time, that has changed. Now my love for this album runs much deeper than many others. Looking back on those parties that left me cold, I now see the unbridled joy and shared experience that united those middle-aged dancers with the youthful, hedonistic bodies that burned the disco floors out in New York and beyond. Disco itself was about creating a safe space for the most marginalized in society—a place to be free of the shackles of prejudice and lost in the joy and freedom that the music brought. Those ladies who danced on the uncomfortably sticky church hall floors may have found themselves reunited with the past versions of themselves or discovered a new, carefree version of them, freed from the various pressures of life for those brief, snatched moments. No kids, no husband, no work—nothing but the heavenly Sledge sisters accompanying Chic’s unique sound.

It almost seems unfair that one album should be so full of certified classic dancefloor fillers. Opening with “He’s The Greatest Dancer” is apt given the sheer danceability of most of the album and to be able to follow it with wonders like “Lost In Music,” “Thinking Of You” and “We Are Family” is outrageous.

There are other charms though, beyond the songs that demand your feet move. I’ve always been partial to these throughout Chic’s catalogue too (think “Warm Summer Night”) and here, my favorite of the slower tracks is “Easier To Love.” But all of the album hangs together perfectly like a made-to-measure suit.

When you listen to this album armed with knowledge of the “disco sucks” movement, the stark contrast between the welcoming, inclusive and open-hearted joy that Sister Sledge embody and the malevolent spirit of those who took extreme lengths to deal with something they didn’t like being popular is as clear as day. But still, somehow, the same enmity persists in almost every strain of human existence, making this album more important than ever given the human race’s seemingly endless desire to divide and exclude, rather than cooperate and include. But I know what I choose.

I choose joy, I choose love and I choose dancing (badly).

Listen: