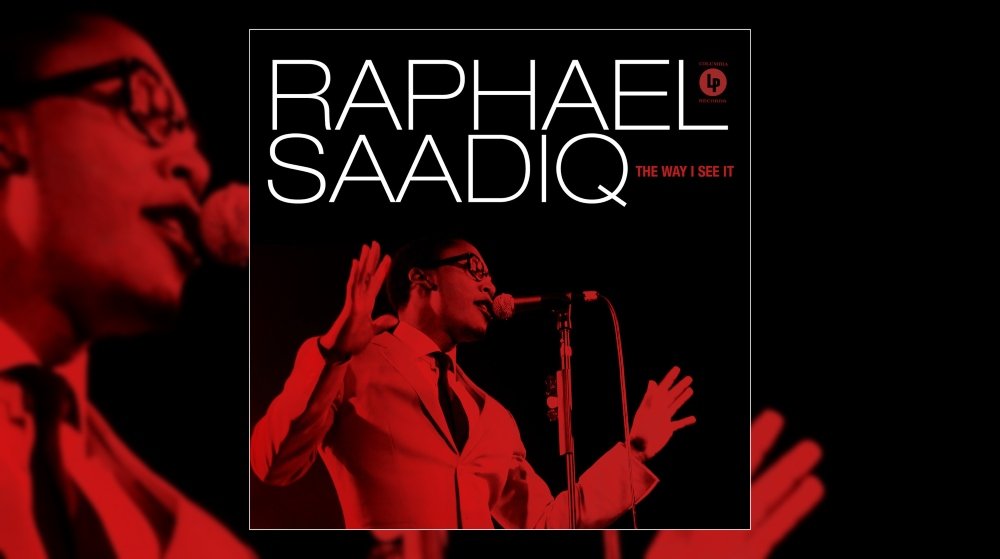

Happy 15th Anniversary to Raphael Saadiq’s third studio album The Way I See It, originally released September 16, 2008.

Raphael Saadiq has always been a bit of a slippery customer. I don’t mean that in a derogatory way, rather that he is difficult to pin down for too long. His career has twisted and turned this way and that—one minute he’s in a supergroup, next he’s writing and producing smash hits for other people, and finally he’s a solo star in his own right.

Even those solo albums have had entirely different characters. His 2002 solo debut Instant Vintage was an eclectic mix of psychedelic soul, funk and neo-soul, while follow up Ray (2004) reveled in a Blaxploitation era soul-funk axiom. In a rare interview with The Quietus, Saadiq would lay claim to being 5 years ahead of the music industry curve. And with those two albums, a genuine case can be made.

His third solo album The Way I See It released 15 years ago in 2008, is slightly problematic with respect to that idea though. Arriving on the coattails of Amy Winehouse’s immensely popular album Back to Black, Saadiq’s album seemed to fit perfectly into the zeitgeist alongside artists like Duffy in rediscovering the joys of Motown and ‘60s soul for a new era.

But anyone who knew Saadiq’s work would know that there was no bandwagonism on his part. There had always been a deeply held love for the organic textures and classic crafting of soul music ingrained throughout his catalogue. While Winehouse favored the female vocal groups of the early-mid ‘60s as her jump off point, Saadiq’s inspiration became obvious with one look at the album cover.

With thick, black rimmed spectacles, pale suit and hands flared mid performance, Saadiq flashed a David Ruffin aesthetic that immediately conjured up the golden era of Motown. Finger snaps, coordinated dance steps and straight up, earnest romantic notions of love—the whole shebang.

But as you’d expect from someone of Saadiq’s pedigree, things went deeper than any surface similarities to those songs of yore. Not content with simply structuring songs in a Motown fashion, he and his partner in crime, recording engineer Charles Brungardt, eschewed their normal approach and decided to revert to the techniques and equipment from the era they were so enamored of.

Watch the Official Videos:

Having discovered some equipment set to be “retired” outside a studio, they set about returning it to its rightful glory and used it to create an album that never veers towards pastiche and remains as an homage to a golden era. In doing such an incredible job of staying true to the moment, there are times when the odd refrain or flurry of notes make you think it’s been lifted from a Motown favorite, but that is almost inevitable given how convincing the work is.

That fundamental and overwhelming love of the era and genre is evident from the first seconds of the album. With its mid-tempo swinging groove, strongly reminiscent of “How Sweet It Is (To Be Loved By You),” “Sure Hope You Mean It” oozes charm, innocence and boasts a further link to the era-defining days of Detroit based Motown.

For as well as the album’s obvious musical and lyrical touchstones, there are some illustrious personnel who provide a physical and experiential link to those halcyon days. There, on tambourine and vibraphone is Jack Ashford, whilst the string arrangements are by Paul Riser.

Both of these men are part of the legendary set of musicians who soundtracked a musical movement, playing on scores of hit records from Motown. These two “Funk Brothers” represent an indelible link to an exceptional cultural and societal movement. If they haven’t told their stories yet, it should be someone’s job to record those oral histories and preserve them for posterity and future generations.

Soapbox moment over, we should return to Raphael Saadiq’s glorious love letter to the Motown strands of soul music’s DNA. “Keep Marchin’” is a prime example of the Motown lyrical style writ large. There’s no hip-hop inspired rage in dealing with injustice. There’s no openly resistant call to arms. Instead, there’s an exhortation to stay positive and non-violent and to continue the march to freedom. All of which might seem unnecessary if the exact same injustices of the ‘60s didn’t still burn so brightly in the 21st Century.

Throughout the album, it is very difficult to avoid distraction at first, as Saadiq runs the full gamut of Motown inspired influences. To a dedicated fan of soul music there is a temptation to spend the initial listen in spotting echoes of classic Motown cuts, but that is to miss the chance to lose yourself in the charmingly effortless quality of the songwriting. Relax into the album and it rewards you at every turn.

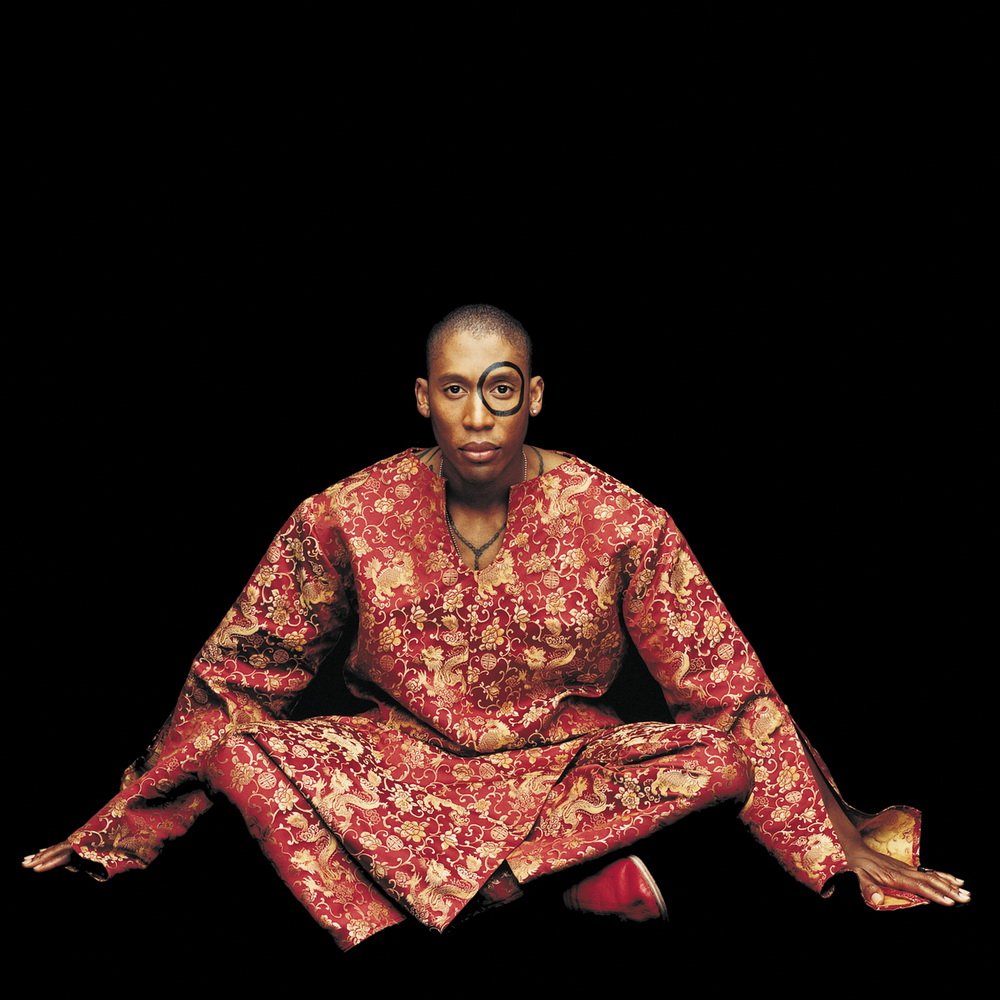

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about Raphael Saadiq:

There’s the insistent driving groove of “100 Yard Dash,” the swooning romanticism of the strings on “Just One Kiss” and the teenage dream lushness of “Calling.” Every tune brings something new to the table and demonstrates an artist (and associated collaborators) with the ability to craft winning tunes in virtually any iteration of soul music.

The delights don’t end there though. The driving backbeat of “Staying In Love” is infectious to the point of addiction. “Never Give You Up” has no lesser commendation than the fact that it features Stevie Wonder on harmonica and the same innocently romantic notions that provide the common thread that helps create an indelible link to the records that Saadiq clearly adores.

Standing in the midst of all that quality material, are two absolute giants of songs. To be head and shoulders above the rest of the excellent album is some feat, but they manage to outdo everything else on show. “Oh Girl” floats effortlessly along on a wave of sitar, strings (led by concert master Brent Fischer, son of legendary string arranger Clare Fischer) and Saadiq’s understated falsetto brilliance. It is a piece of perfection that stands as both a fitting tribute to that bygone era and as a thrilling, spinetingling tale of romantic devotion.

But my favorite song is the hyperactively musical, yet lyrically downbeat genius of “Big Easy.” It owes more than its name to New Orleans though. The contrast between the jumping, effervescent music and (literally) morbid lyrics is a reflection of the funeral marches of the Big Easy—the crushing contrast of joy and pain, of heartbreak and solace. Lyrically it begins like any song of love lost: “Somebody tell me / What’s going wrong / I ain’t seen my baby / In far too long.” But very quickly, it becomes crushingly clear what it is really about: “Somebody please tell me / What’s going wrong / They say them levees broke / And my baby’s gone.” Before yet more agony is inflicted: “I miss my only child / I ain’t seen her since that night / She left home about eight / Never to return / Our bodies floatin’. . .floatin’ in that river.” It is all of life distilled into a 3-minute song. And it is perfect.

Saadiq would turn the clock slightly further back for his next album 2011’s Stone Rollin’ and tackle the earliest foundations of soul music, but it didn’t make any difference to the quality of the material—it was just as stellar. All of which set the heart a flutter when it was clear that a new album was in the pipeline. That album manifested eight years later as Jimmy Lee (2019) and it proved to be worth waiting for. After all, Raphael Saadiq never lets you down.

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2018 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.