Happy 35th Anniversary to the Pump Up The Volume Soundtrack, originally released August 14, 1990.

“Do you ever get the feeling that everything in America is completely fucked-up?”

There’s something uncanny and maybe even a bit little quaint about watching a movie from 35 years ago—on DVD no less—where the camera pans over suburban sprawl as Christian Slater contemplates the fucked-up state of America in the Neighties. Particularly in 2025 when Donald Trump, a convicted felon, is president; people are being snatched off the streets and sent to foreign gulags; and millions of people are about to be kicked off of Medicaid.

It’s easy to believe, by kneejerk comparison, that there was nothing legitimate to bitch about in 1990. It’s easy to forget 12 years of Reagan and Bush. It’s easy to forget, prior to the internet, the feeling of being voiceless.

And it’s easy to forget how Pump Up The Volume predicted, and helped spark, a ’90s teenage counterculture by simply depicting a shy teen with a ham radio who questions adult wisdom, challenges corruption at his school, blasts alternative music, and encourages his peers to “talk hard.”

To truly appreciate Pump Up The Volume, however, you have to go back to the 1960s. Not only because that era’s abandoned ideals run like a convulsive undercurrent throughout the film, but also because it’s where director Allan Moyle discovered the seed of an idea to center Pump Up The Volume around a teen with a pirate radio station.

In the mid-’60s, rock ‘n’ roll was scant on the mainstream British airwaves, with the BBC broadcasting a mere six hours of popular music each week. And so a band of rebel DJs began broadcasting from old fishing ships off the Eastern coast of England, which technically put them in international waters and out of the authorities’ jurisdiction. The DJs’ playlists were inspired by American Top 40 stations, which, ironically, were filled with the British rock of the era. The pirates would blast hits by The Rolling Stones, The Who, and The Hollies as more and more Brits began tuning in each week, eventually forming an audience of millions. By 1967, the British government made it illegal to supply advertising and even music, fuel, food, and water to the pirate-radio ships, which ended up putting the kibosh on the broadcasts.

In 2009, the film Pirate Radio would end up documenting this history, but when Alan Moyle thought of using it as a kernel for his 1990 teen drama, it was a mostly forgotten moment. “I was kind of disappointed when I saw the movie … or maybe I was jealous,” Moyle told Vice in 2015. “And before Pump Up The Volume was Good Morning Vietnam and Talk Radio. So it wasn’t the most original idea, but I wrote it about a suicidal young guy who was announcing his own suicide on the radio.”

It was a macabre idea for a teen movie, but even Moyle’s suicidal DJ had his roots in actual 1960s history. Growing up in small-town Quebec, Moyle had a high-school classmate who had an amateur printing press in his basement. The classmate would write fiery screeds and then distribute them via anonymous pamphlets all over the school. Some of them were deeply felt musings on life, while others boldly criticized the principal and the school itself. Moyle admired this student from afar, and regarded him as someone unusually sophisticated for his age and his environment.

But then one day, the young man walked into the woods and shot himself with a .22 rifle. His suicide deeply affected Moyle. “I was upset because I could see that he was dark and I was attracted to that, but also afraid of it,” Moyle told The Ringer. “If he’d gotten to university or a big city, he would have found people like him, but he was too young. I thought here’s a guy, a voice crying out in the wilderness ... but he’s more than this town.”

The initial script for Moyle’s film was titled Radio Death, and it centered on a teenage pirate-radio DJ’s final broadcast where he contemplates suicide, but as the show continues and the audience grows, it becomes apparent that he doesn’t intend to go through with the act.

Prior to writing the script, Moyle had directed the 1980 film Times Square, a now-cult classic with a killer soundtrack about two teens who escape from a psychiatric hospital, form a band, and with the help of a radio DJ (Tim Curry), become New York punk heroes. Despite its now-reverent spot in the rock-movie canon, working on Times Square was traumatizing for Moyle.

During post-production, producer Robert Stigwood (of Saturday Night Fever and Grease) wrested control of the film and cut scenes that made it obvious that there was a lesbian relationship between the two main characters. Furious, Moyle decided to only write for movies and never direct again. However, that would change at the end of the ’80s when he ended up taking a meeting with a young movie exec named Sandy Stern.

“Our first meeting is actually something that I remember like it was yesterday,” recalls Stern. He had received a 45-page treatment (a detailed summary) for Moyle’s script, and found it riveting. “Part of it for me was [the] kid who had a pirate radio station and was broadcasting from his basement. When I was in my teenage years, the radio was my understanding, the voice that [said] there was a world outside the suburban neighborhood that I felt enslaved in at the time.”

So Stern arranged for a meeting at the White Horse Tavern in New York. He was excited about the project, but at that point the treatment he’d read had no ending. The two men sat down, and Moyle, wearing a crisp white shirt, ordered a glass of red wine. Stern was nervous, because he was going to propose a third act for the movie that he wasn’t sure Moyle would like. After Stern made his pitch, Moyle stood up and said simply, “Oh my god.” But then Moyle went to bear-hug him across the table, and red wine went flying everywhere, all over his white shirt. “And he said, ‘We have to do this together. This is the movie I want to make, and I want to make it with you,’” Stern remembers.

The most notable change Stern had suggested was removing the DJ’s suicidal ideation as the central theme, and having a side character introduce the issue of suicide as merely one topic the film explored. The two men toiled over the script for the next year. As they began looking into financing and distribution for the film, they also began searching for an actor to play their main character. Moyle’s first choice was John Cusack, who he felt had a natural darkness. Cusack was flattered by the opportunity, but he had recently decided that Say Anything was going to be his last teenage role.

Moyle had seen Christian Slater in Gleaming The Cube (1989), but he wasn’t too impressed. Slater’s dark portrayal of the maniacal J.D. in 1988’s Heathers, however, sold him. In the spring of 1989, Moyle and Stern sent Slater their script, and then took a lunch meeting with the actor at the Sunset Marquis in Hollywood. Typically, stars never agree to a project during a first meeting, but Slater resolutely told them he would take it.

To this day, Slater has a deep fondness for Pump Up The Volume, telling Variety in 2020, “That is my favorite movie, I think, that I’ve ever done [and], to a large degree, favorite job. I felt like it was ahead of its time. It wasn’t a typical high school movie, and it really did get into some of the darker, more gruesome details of what it’s actually like to be a teenager in high school.”

Slater truly does shine as Mark Hunter, a teen whose parents have moved him across the country from New York to suburban Arizona. Shy and anxious, Mark finds that the only way he can talk to his peers at Hubert Humphrey High is under the cover of night behind a microphone in his basement studio, while assuming the persona of Happy Harry Hard-On, a shock-jock who curses like a sailor and simulates masturbation. He blasts songs by the Beastie Boys and the Descendents, and reads letters from listeners that begin to serve as a sort of group therapy. Eventually, once he learns of corruption at his school, Mark encourages his fellow students to rise up against the principal and the guidance counselor, who are unfairly expelling students due to teen pregnancy and low test scores.

After securing Slater for their lead, Moyle and Stern began talks with Island Pictures about making Pump Up The Volume, but the deal dissolved once Island started making demands about the character Malcolm Kaiser, a lonely listener of Hard Harry’s show—the character who eventually commits suicide. The studio made it clear that Malcolm should not be gay. Moyle and Stern refused to change the script, although in the movie’s final version it isn’t stated specifically that he’s gay. “It was told to me, but never clarified with the audience, which I liked because it left room for all of the things that we struggle with,” explains Anthony Lucero, the actor who portrayed Malcolm. (It’s Malcolm’s suicide that eventually gives the school administration an excuse to go after Mark, and the FCC arrives to tamp down on Hard Harry’s show.)

In another scene, however, we do eventually meet an openly gay character, who calls into the show to recount a cruel homophobic prank perpetrated by fellow classmates. As he’s talking with Harry, we see the faces of the teenage listeners, who clearly feel nothing but empathy. It’s a dynamic scene. In 1990, this was years before sensitive portrayals of LGBTQ+ young people became more of a decade norm—before Pedro Zamora on The Real World, Rickie Vasquez on My So-Called Life, and Brandon Teena in Boys Don’t Cry.

Listen to the Playlist:

After the disaster with Island, Moyle and Stern eventually found a backer in New Line Cinema, which, despite its major-studio reputation, had also taken on hip projects like Sid & Nancy and John Waters’ collection of envelope-pushing films. Still, Moyle, who adored underground music, would have to make concessions, like naming the film Pump Up The Volume after a mainstream late-’80s dance hit by M|A|R|R|S.

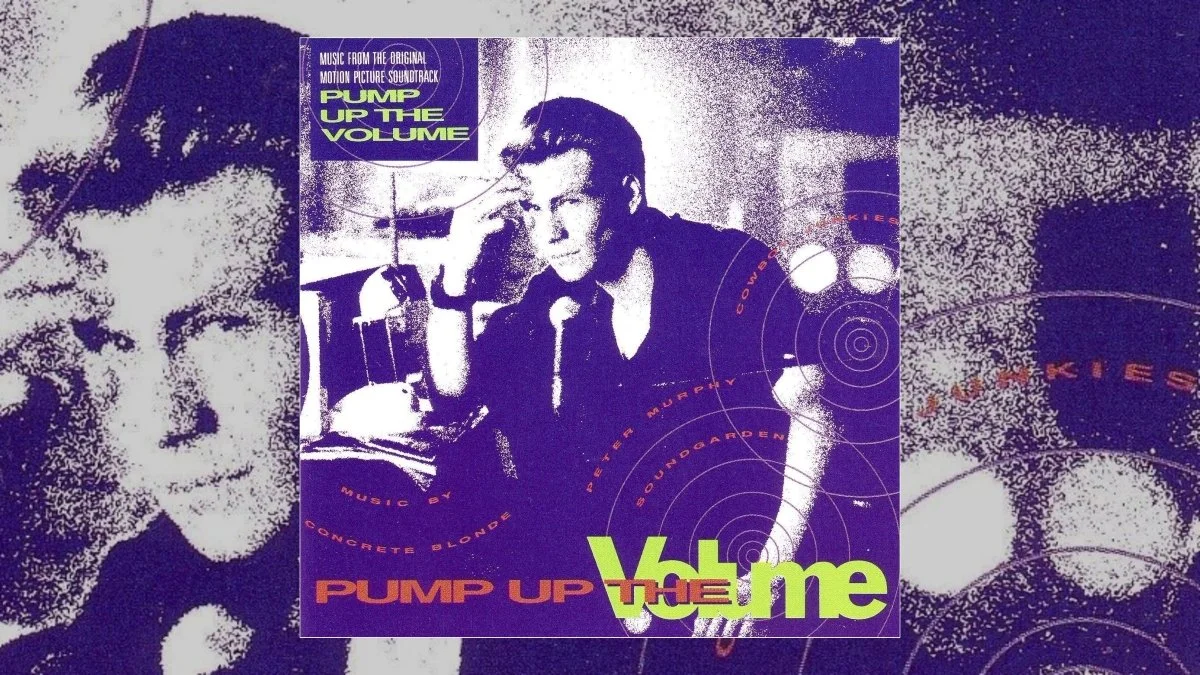

Still, much of Pump Up The Volume revolves around Harry and his unconventional musical tastes. In the same way that Moyle’s defiance towards homophobia had been shaped by working on Times Square, he also brought the underground instincts that had been showcased on that film’s soundtrack to Pump Up The Volume. Featuring Sonic Youth, Concrete Blonde, Soundgarden, and the Pixies, Pump Up The Volume’s soundtrack would end up introducing its teenage audience to bands they’d never heard of—a year prior to the alternative explosion that Nirvana’s Nevermind (1991) would ignite.

“You have to remember where music was at the time,” recalled Dave Grohl at SXSW in 2013, listing Billboard’s Top 10 artists of 1990 when Nirvana was in the midst of signing with a major label (Bon Jovi, Billy Idol, En Vogue, Phil Collins, Mariah Carey, Madonna, Bell Biv DeVoe, Sinéad O’Connor, Roxette, and Wilson Phillips). “How Kurt could even think we’d make a ripple in this ridiculous mainstream world of polished pop music was beyond me.”

Pump Up The Volume absolutely paved the way. “It felt like something was happening,” observes Samantha Mathis, who was 19 when she portrayed Mark’s poetry-writing love interest Nora in the film. “We were moving away from that synthesized sort of sound and moving into something edgier, and we had the dissonance of being around the ‘greed is good’ era of filmmaking and finance in the world. There was anger, and I thought Allan really tapped into that with this movie.”

Moyle understood that there was no way Hard Harry could deliver blistering screeds on how his Boomer parents—and the school faculty—had sold out ’60s ideals while blasting Phil Collins. The soundtrack and film itself borrows from the '60s—Leonard Cohen, the MC5, Sly Stone, and Mark’s obsession with Lenny Bruce’s How to Talk Dirty and Influence People—but it doesn't idolize the era. Instead, it filters those influences through a late '80s/early ’90s haze of cultural exhaustion, skepticism, and Reagan/Bush fatigue. The soundtrack's juxtaposition of counterculture relics with then-rising bands like Soundgarden and Sonic Youth forecasts the coming explosion of '90s alternative, but the vibe is still characteristically Neighties—in-between, defiant, in honest search of definition and meaning.

You didn’t have to be familiar with any of the ‘60s references, however, to walk away from Pump Up The Volume with an understanding that the film was calling for more impassioned engagement, and a deeper connection to one’s community. Is it any wonder then that, as the ’90s wore on, Gen X teens would embrace causes such as Riot Grrrl, Rock the Vote, HIV/AIDS activism, Food Not Bombs, Save The Whales, and Free Tibet? That they would take part in the WTO protests at decade’s end, or that Julia Butterfly Hill would climb a California redwood in 1997 and live in it for two years in order to save a forest? That Lollapalooza would become our Woodstock, even as Woodstock, too, was reinstated? Gen X is often dismissed for its apathy, but for those of us in the generation’s second wave, that’s simply not the truth.

At the same time, the film captured our awkward, stubborn ’80s-ness—the part everyone wants to forget still existed in 1990. “It felt like the eighties might live forever when the Berlin Wall fell in November of ’89, but that was actually the onset of the euthanasia (though it took another two years for the patient to die),” writes Chuck Klosterman in The Nineties.

Some of the best scenes in Pump Up The Volume are when the camera pans the teenage bedrooms. On the riveted listeners, you see Forenza sweaters, ugly ’80s glasses, mullets, and crunchy perms. It’s a reminder to stay humble, and it’s a reminder of just how much the radio meant to us.

I still remember sleepovers gathered around the radio at Jennifer’s house, calling the late-night DJ to make requests for boys who likely weren’t listening. Or keeping a blank cassette in the boombox at all times to hit “record” whenever a coveted song came on. It was a lineage I shared with my mother and her friends, who would drive around their farm town in ’60s Minnesota in search of a signal strong enough to catch Wolfman Jack on a station out of Detroit. And yet all of that strange magic would be gone with the internet—and we didn’t even know it.

Pump Up The Volume’s soundtrack kicks off with Concrete Blonde’s cover of Leonard Cohen’s “Everybody Knows,” Johnette Napolitano singing in a sultry, whiskey-soaked tone. Cohen’s original version of “Everybody Knows” became the semi-official theme of Hard Harry’s show after Moyle had fallen in love with the brooding song, which his then-wife had worked on as a sound engineer.

But not everyone was a fan. “The head of New Line, Bob Shaye, thought Cohen’s version was too down head to be the opening song of the movie. He said, ‘God that’s dreary!’” Moyle recalls. So the studio had Concrete Blonde, a band with indie cred, do a cover. The Cohen song, however, was still used throughout the film, no doubt due to Cohen’s ‘60s roots and its anti-establishment message.

The album then takes a romantic, melancholy turn with Ivan Neville’s soulful “Why Can’t I Fall In Love.” After all, it’s Mark’s relationship with Nora— “The Eat Me, Beat Me Lady” as he nicknames her due to the S&M-tinged poetry she sends him—that allows him to start believing in a cause bigger than himself. Meanwhile, Liquid Jesus performs a very ’80s-sounding version of the 1969 Sly Stone song “Stand!,” which calls for standing up for one’s principles and community.

Next up comes “Wave of Mutilation (U.K. Surf),” which would introduce many listeners to the Pixies for the first time, prior to Kurt Cobain’s naming them as a major Nirvana influence. Moyle liked the song because it references a Charles Manson lyric, “Cease to Exist,” which was released by the Beach Boys as “Learn Not To Love,” about the tensions Manson witnessed between the Wilson brothers (Manson, oddly, struck up a friendship with Dennis in 1968).

Peter Murphy’s “I’ve Got A Secret Miniature Camera” contributes a quirky, lo-fi ’80s vibe to the soundtrack, while a version of “Kick Out The Jams” by Bad Brains with Henry Rollins adds a snarling, ‘80s-steeped take on the late-’60s proto-punk classic. In the movie, it plays over students causing mayhem as Mark and Nora are chased by the Feds.

Above The Law’s “Freedom of Speech” offers a welcome hip-hop addition—a genre that was about to explode alongside grunge. And speaking of grunge, Soundgarden’s trippy, psychedelic “Heretic” draws parallels between Hard Harry’s plight and another bygone era: “Heretic / Burn at the stake / Witch, yeah, float like a log.”

The chugging “Titanium Exposé” by Sonic Youth was inspired by the band’s bohemian beginnings in early-’80s New York, when Thurston Moore and Kim Gordon were falling in love. “I wanted to write a straight-ahead urban love song, and when I say urban I mean I always love ideas about two people living within their means,” Moore said. “Artists in a place of poverty, but you’re completely enriched by the creative connection you have.”

Cowboy Junkies’ “Me And The Devil Blues” is a remake of a song by Robert Johnson, who the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame describes as “the first-ever rock star.” The album ends with “Tale O’ The Twister” by Chagall Guevara, the first verse describing the type of Manic Panic alterna-chick you’d see at Lollapalooza: “She was a cool blue redhead / She was a virgin vixen / She had the eyes of Lassie / She had the lips of Nixon.”

In the final scene of Pump Up The Volume, as Hard Harry is being pushed into a squad car, he raises his fist and encourages his listeners to “steal the air.” We then hear a gathering of multiple voices, all with their own pirate stations. “You know how it ends with these voices announcing themselves?” Moyle said. “That is so internet! Blogs and podcasts! That scene still gives me the shivers because it’s such a powerful idea that kids in their rooms all over America can be expressed. And then wow, it happened!”

Even though the film predicted the internet, it’s because of its music that neither the movie—nor the soundtrack—has a presence on the internet today. Every single one of the songs that appear in Pump Up The Volume would have to be re-licensed before the movie could be legally available, a complex process due to New Line having been purchased by Turner Broadcasting in ’94 and, through a tangled web of corporate mergers, the catalog being owned by Warner Bros. today. Still, the film is available on DVD, and the soundtrack on CD. And, admittedly, there was something very fun and analog—yet embarrassingly teenager—about curling up on my bed with a boombox, writing about a dusty, but still relevant, ancient artifact from the Neighties.