Happy 30th Anniversary to Nas’ debut album Illmatic, originally released April 19, 1994.

You love to hear the story again and again: in a world where the Reagan-and-Crack era’s devastating effects loomed large over dilapidated Black neighborhoods, California rappers ruled the charts, and “Keep It Real” was little more than a shrewd marketing catchphrase, one man emerged from the federally-funded dungeons of Queensbridge with a debut LP poised to swivel the limelight back towards hip-hop’s birthplace, restore dignity to his post-Bridge Wars home, and become the greatest release of the genre’s second golden age, if not of all time.

Released on April 19, 1994, Illmatic was the long-awaited product of a laborious two-year search for the perfect beats to complement its author’s densely descriptive verses. So anticipated was its arrival that bootleg copies permeated New York City well in advance, causing Columbia Records to rush the album onto shelves to alleviate lost profitability and relevance. The result was a record 3-4 songs and 10-15 minutes shorter than your average, which simultaneously left no room for filler, and fans salivating for more.

As a testament to Nas’ unparalleled prowess, he generated this fervor based solely on two shine-stealing posse cut appearances (Main Source’s “Live At The Barbeque” and executive producer MC Serch’s “Back To The Grill”) and “Halftime,” the debut single from the soundtrack of 1992’s Zebrahead, a film best remembered for having a soundtrack that featured “Halftime.” While he grabbed ears on these early records with anti-religion shock value (“When I was 12, I went to hell for snuffing Jesus,” “I’m waving automatic guns at nuns”), it was his seemingly effortless ability to combine extreme imagery with intricate rhyme schemes that held them captive and eager for more.

Nas’ uncanny gift for making audio visual is in full effect on Illmatic, but instead of kidnapping first ladies sans plans or stunning you with STD similes, he uses his powers to make his world yours. Whether you were an LA native, Australian citizen, or a Midwestern hip-hoppin’ shorty wop, a close listen to this album was enough to transport you to the project staircases and benches Nas used his talent to eventually escape.

Unlike rappers who relied on tongue twisting, shouting, or sing-songy flows to make waves, Nas used the fluidity of his natural voice to bring his rhyme books to life. Those pages contained lines far more poetic than most emcees could muster: “It drops deep, as it does on my breath / I never sleep, 'cause sleep is the cousin of death / Beyond the walls of intelligence, life is defined,” “I need a new nigga for this black cloud to follow / ‘Cause while it's over me, it's too dark to see tomorrow,” “Sentence begins indented / with formality / My duration's infinite, money-wise or physiology.”

Watch the Official Videos:

Nas’ exceptionally extensive vocabulary and expressive eloquence were perhaps even more remarkable coming from an 18-20-year-old ninth-grade dropout (“Never liked the shit from day one”), but Nas’ story and the narratives told on this album are those of countless Black and Latino children with infinite potential who are born under systemic oppression into neighborhoods that dare them to survive, cops who threaten their existence, and schools that crush their imaginations.

While this unfortunately universal truth makes the album more relatable, it’s Nas’ position as an embedded reporter, rather than a foot soldier, in the outdoor street war that both endeared him to listeners and further distanced him from contemporaries. Make no mistake, Nas had to be as hard and cold as the pavement where gunshot wounds ended the life of his best friend and early music partner Ill Will, but he relegated himself to observing, rather than participating in some of the harsher offenses occurring in his circumference.

Where many rappers (including Nas himself, on pre-album tracks like “I’m A Villain”) were and are eager to cast themselves as the star of their own gangsta fairytales, the Nas of Illmatic would rather “Relax and strive” or “Lamp, ‘cause a crime couldn’t beat a rhyme.” He gave up a short stint as a failed drug dealer years earlier but still hung with friends who sold crack. The precipice of ruthlessness was never far from his feet: “Could use a gun, son, but fuck being a wanted man / But if I hit rock bottom, then I'ma be the Son of Sam.”

But as weary Nas fans know, otherworldly lyrics and dexterous delivery alone do not a masterpiece make. Illmatic’s mythical status stems from beats as meticulously crafted as its rhymes. While the LP is notoriously light on rap personnel (his homie AZ scored a deal with EMI from its only guest appearance), Nas, with the connections of mentor Large Professor, assembled the Super Friends of New York hip-hop production with Gang Starr’s DJ Premier, A Tribe Called Quest’s Q-Tip, and Pete Rock of “& C.L. Smooth” fame. Nas’ childhood cohort L.E.S. rounded out the quintet. It was not uncommon for solo rap albums to have multiple beatsmiths, but they were usually members of the same crew or the label’s in-house squad. Illmatic was arguably the first to take a Dream Team approach to sound cultivation.

“Team” is the operative word here. This wasn’t a case of producers submitting tracks through a messenger or record label rep. Large Professor drove Nas to Phife’s grandmother’s basement to hear the “Smilin’ Billy Suite Part II” loop around which Q-Tip constructed “One Love,” and to Pete Rock’s infamous underground cavern to unearth “The World Is Yours.” Premier was present when Pete Rock laid the scratches for “The World Is Yours,” and met Nas’ father Olu Dara and L.E.S. during the “Life’s A Bitch” session.

Lest you think this is some old head “Back in my day people had to carry reels 20 miles uphill in the snow!” signifying. Illmatic’s communal aspect bred a friendly competition that pushed all involved to bring their A+ game with extra credit. DJ Premier’s early “Represent” mix featured a rugged, galloping bass line that while unquestionably dope, might’ve sounded dated today. After hearing Pete Rock and Q-Tip’s uniquely stellar contributions, he felt compelled to go back to the lab and concoct a new formula using, of all things, a motherfucking pipe organ from a silent film soundtrack. In turn, while manning the tables, Pete Rock knew his “The World Is Yours” jigga-jiggas had to be worthy of the DJ standing over his shoulder.

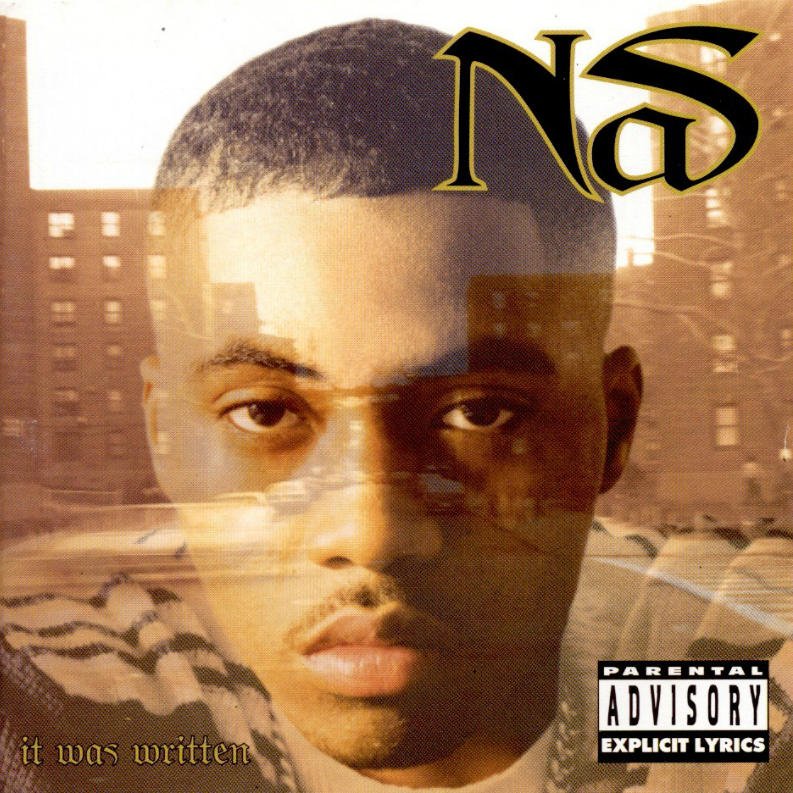

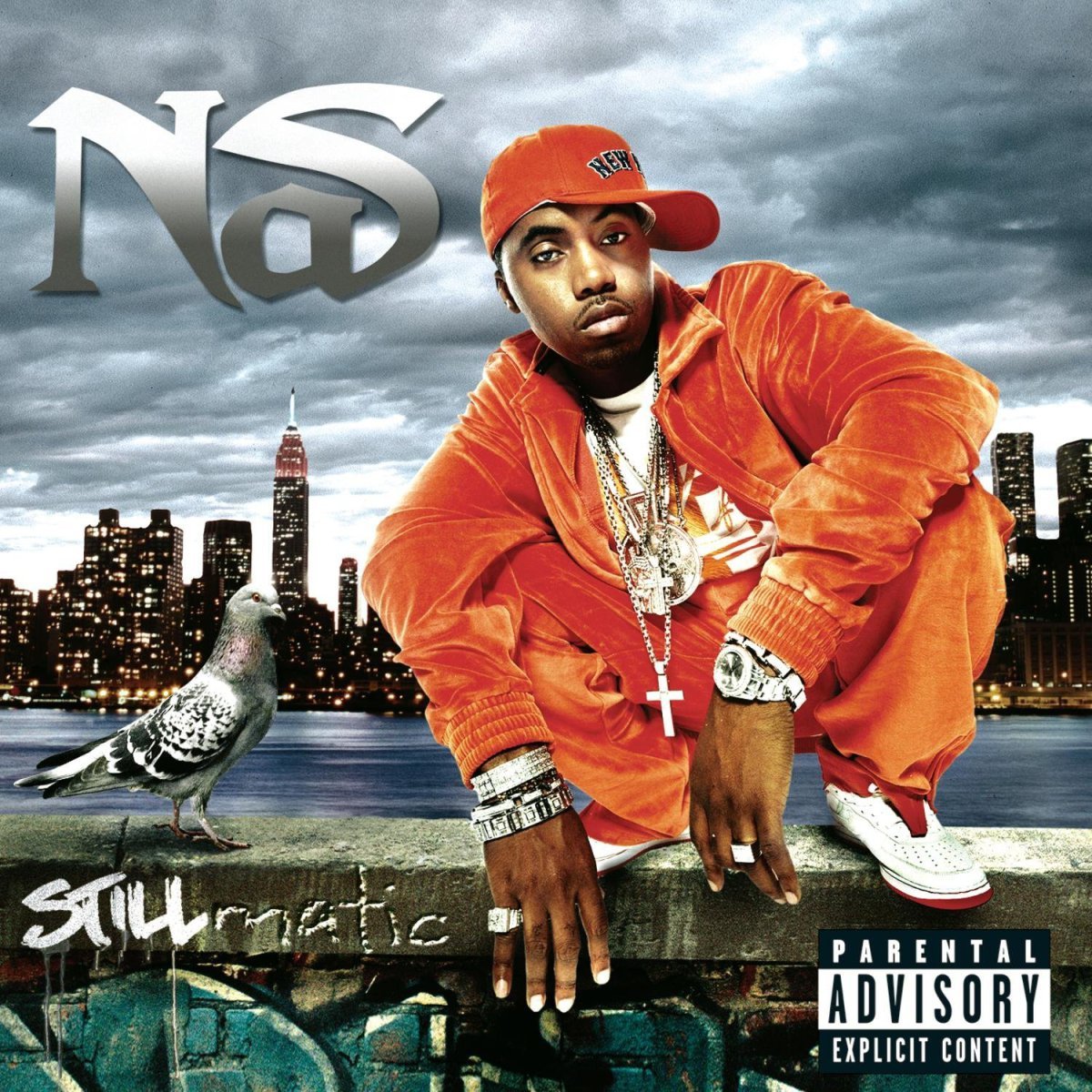

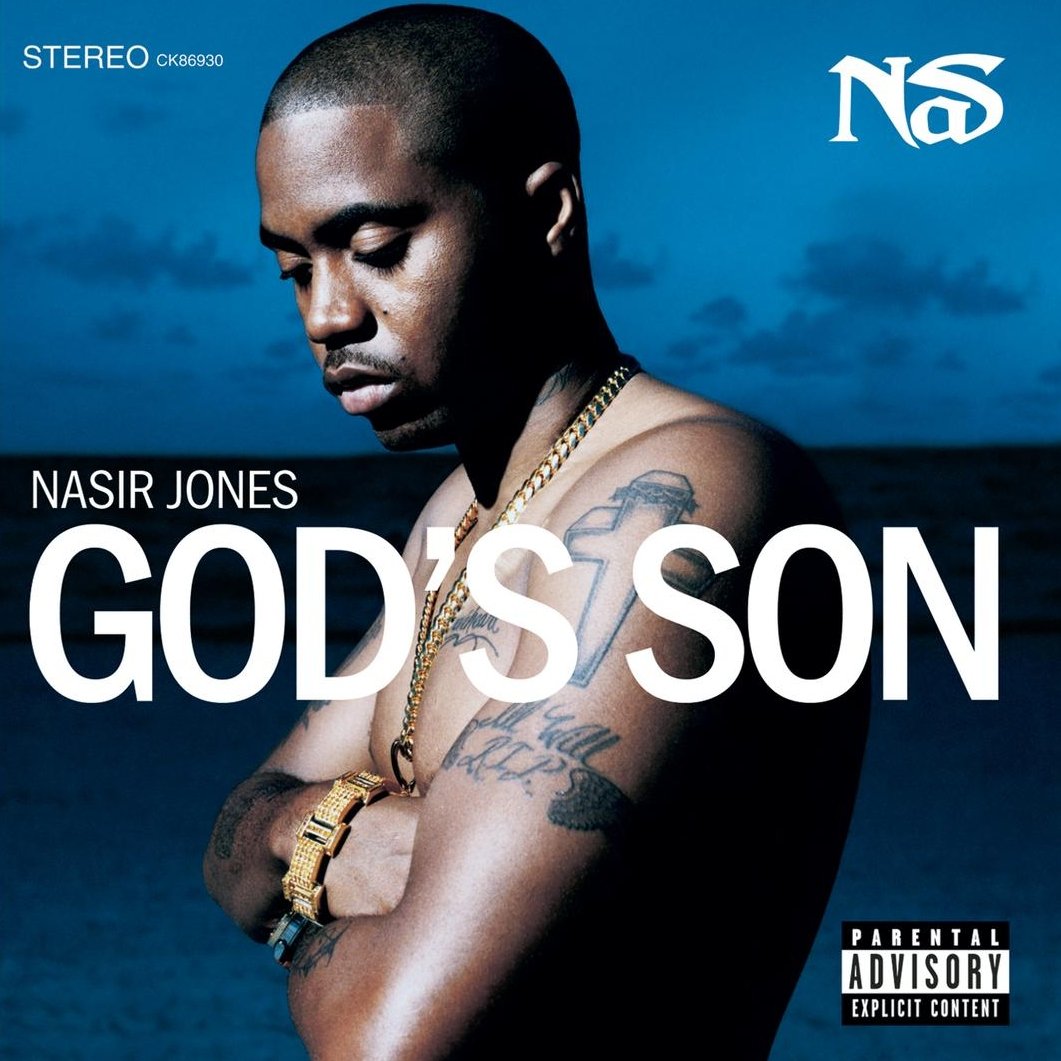

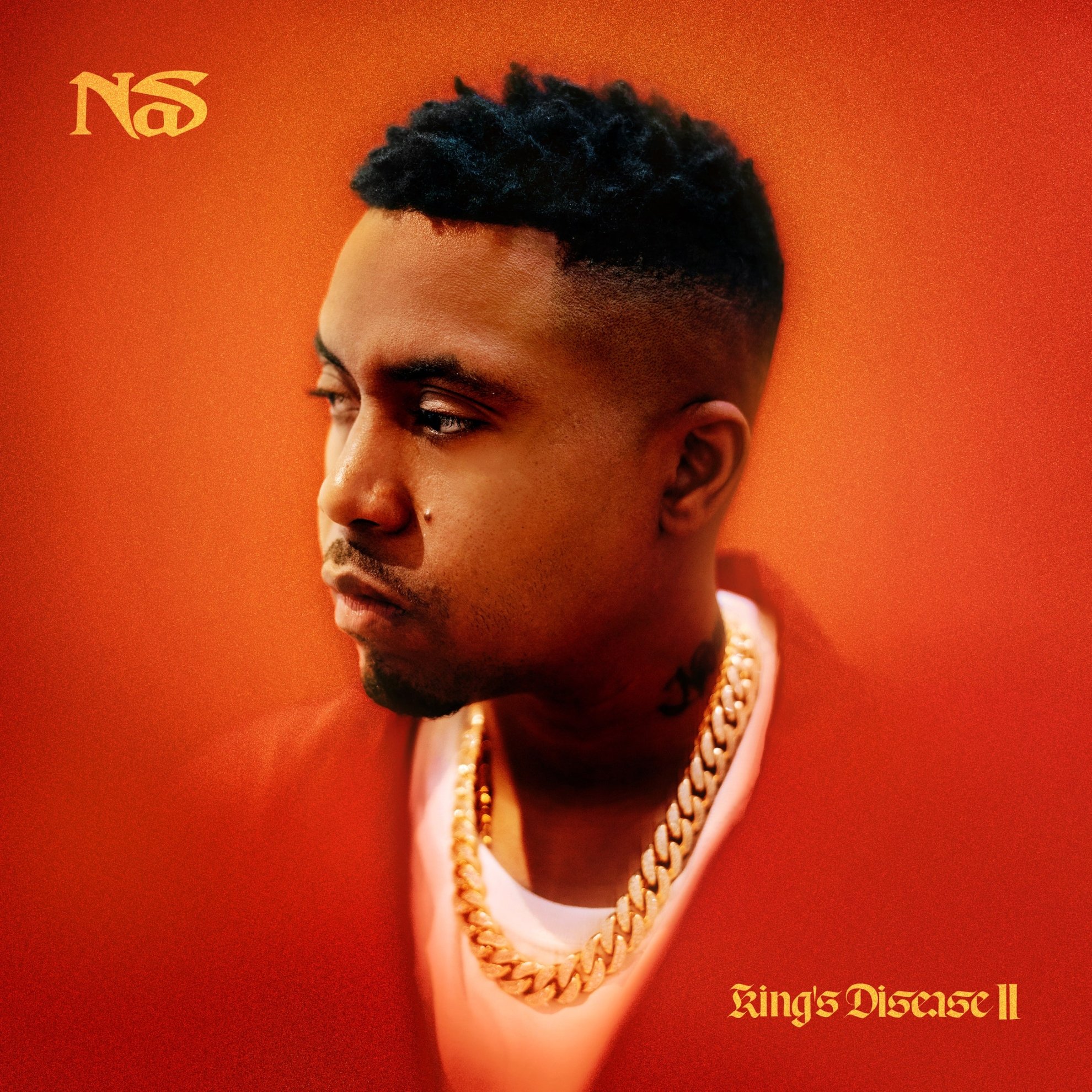

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about Nas:

The album’s musical secret sauce is a frequent stirring of seemingly disparate ingredients. Nas uses L.E.S.’ somber “Yearning For Your Love” intro loop as a backdrop for the album’s most optimistic verse, on a song titled “Life’s A Bitch.” Large Professor transforms the beautifully delicate “Human Nature” into the hardcore elegance of “It Ain’t Hard To Tell.” On “Memory Lane (Sittin’ In Da Park),” DJ Premier slows the sprightly Hammond organ, harmonious vocals, and sitar from Reuben Wilson’s “We’re In Love” and couples them with pounding boom-bap to create a wistful composition that evokes visions of windy NYC nights.

But perhaps the best example of this divine dichotomy lies within “One Love.” The aforementioned Heath Brothers sample’s upright bass and mbira/kalimba plucks might sound more suited for a tropical island’s tourist lobby’s background music than an East Coast rap classic, but here, they provide the perfect sound bed for Nas to lay his letter to a composite of jailed friends, who might fantasize about chilling on such an island to temporarily escape their bleak reality. Such daydreams would certainly work better than Nas’ kites, which while presumably intended to lift spirits, paint a picture of things falling apart back home: Jerome’s niece got shot, an unfaithful partner is more interested in rival crews than keeping in touch, neighborhood children are getting caught up in deadly nighttime maneuvers, and friends are becoming formers and informers.

And then there’s “One Time 4 Your Mind.” On any other 1994 album, its bluesy bass, bustling breakbeat, and audacious lines (“My brain is incarcerated,” “Root for the villain,” “Y'all niggas was born, I shot my way out my mom dukes!”) would be an obvious standout, but sitting shoulder to shoulder with some of the best songs hip-hop’s ever produced, it feels like an older record included to pad out the running time. If nothing else, the fact that its merely-greatness isn’t quite amazing enough to cut the mustard is a testament to the LP’s unprecedented consistency.

The Source instantly hailed Illmatic as a classic upon release, awarding it the coveted once-every-three-years five-mic designation, back when the East Coast magazine’s word mattered, and before ratings and coverage were up for sale. The same April 1994 issue’s artist feature boldly proclaimed Nas to be “The Second Coming"; partially of the similarly tempered and poetic Rakim Allah, but primarily as a single savior sent to deliver New York back to the artistic and commercial forefront it sought since The Chronic and SoundScan came through and crushed the buildings.

While Nas feasibly led the charge to the fulfillment of this destiny, it was not Illmatic that reaped the benefits. Despite universal street and critical acclaim, the album sold well below expectations, perhaps giving us a preview of the eventual underground vs. mainstream split that still permeates this thing of ours. Even The Source, with all its king crowning, fronted on the chip-toothed kid during its infamous August 1995 awards ceremony, where he surprisingly lost Lyricist of the Year and Album of the Year to The Notorious B.I.G. and Ready To Die. That album’s masterful balance of grime and glam, while not as bulletproof as Nas’ debut, became the star-maker many hoped Illmatic would be.

Losing both the sales and credibility wars, Nas found his own Puffy in Steve Stoute, linked up with the newly radio-friendly Trackmasters, and used his immaculate visualizing skills to fashion his Moët-sipping, TEC-holding drug dealer dreams into the Escobar persona of It Was Written (1996), which resulted in radio hits, platinum plaques, and superstardom. While Nas’ vocal instrument was still potent, Illmatic fans couldn’t help but feel the innovator becoming the conformist.

I suppose that’s the gift and the curse of creating such an overwhelmingly powerful opening statement. While Nas created an absolute masterwork that, for many, still serves as a blueprint to the ideal LP, its vast shadow will follow him to every release, where heads will inevitably stand, arms folded, disappointed that the man once again failed to achieve Illmatic status.

Then again, Nas still gets plenty of mileage from his timeless debut, and deservedly so. How many emcees, nay, musicians of any caliber, can say they’ve created a work of art so lauded that documentaries, books, innumerable retrospectives, multiple commemorative reissues, and two tribute albums have been dedicated to its greatness?

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2019 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.