Happy 25th Anniversary to Musiq Soulchild’s debut album Aijuswanaseing, originally released November 14, 2000.

When Kedar Massenburg dropped the epithet “neo-soul” to describe a fresh branding of soul and R&B music that emerged in the US and UK in the early 1990s, he was (perhaps) unaware of the repercussions of doing so. Though clearly trying to provide shorthand for music lovers to identify a fresh take on the scene at the time, he also unwittingly offered another box to confine artists to.

Those concerns notwithstanding, the new era of soul that it ushered in revitalized an organic take on soul that had been threatened with obliteration in the face of New Jack Swing and the juggernaut named hip-hop. While some of the originators of the sound (for example, Meshell Ndegeocello, Joi and Omar Lyefook) went under the radar to the broader music world, the triumvirate of D’Angelo, Erykah Badu and Maxwell hit heights that ensured the label stuck and the scene thrived.

Many of those leading lights have had their epochal albums revisited here at Albumism—I’ve had the pleasure to write about Badu’s debut Baduizm (1997) and D’Angelo’s mesmerizing Voodoo (2000), but there are many other artists who offered their own, unique take on the nascent genre that perhaps don’t get the love their work deserves—among those artists is Musiq Soulchild.

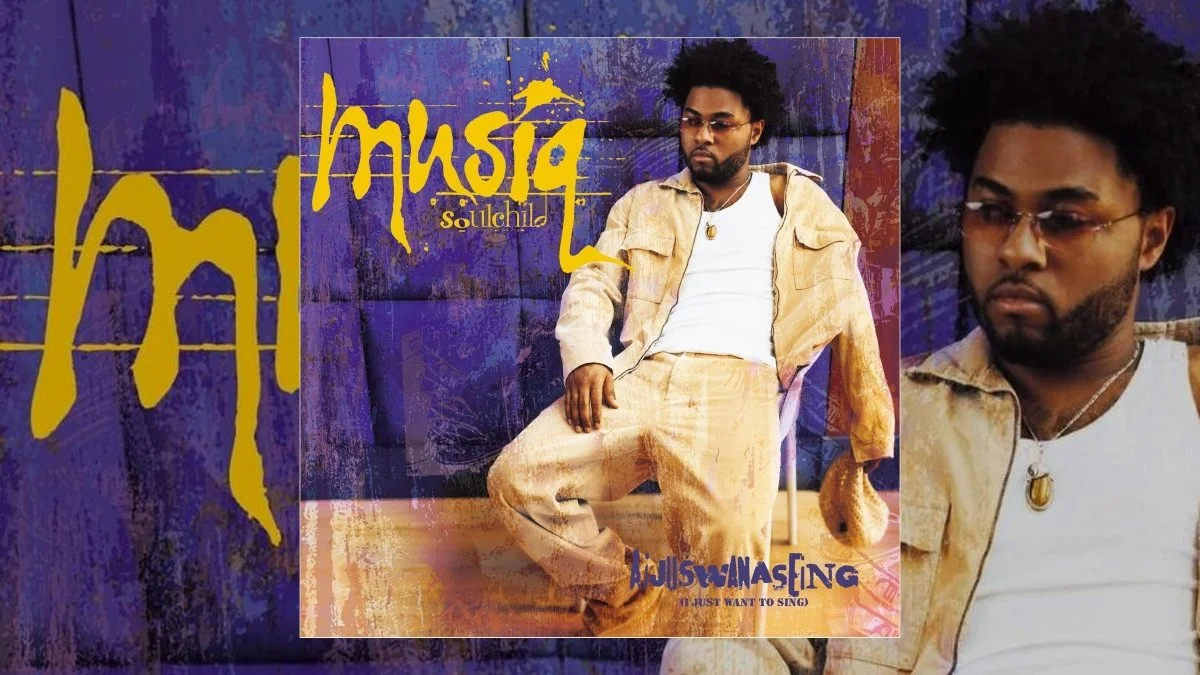

To judge a book by its cover, you’d know that there was something different about this strangely-monikered man from Philadelphia. I distinctly remember seeing his debut CD and being taken aback by the audacity it took to name himself “Musiq.” I mean, you’ve got to have some balls to do that.

But his unique qualities didn’t stop there. The title of his debut took some deciphering too. Written phonetically with no spacing between the words, the style of the title Aijuswanaseing became as much a calling card for him as his music.

In preparation for writing this piece, I noticed that Musiq had taken his turn in the Questlove Supreme Podcast chair and decided to take a listen. What I heard fascinated me in a way that other episodes hadn’t. Listening to Alan Leeds recount his James Brown/Prince/D’Angelo days had been endlessly fascinating in a musicological way, but Musiq’s was something else entirely.

When we write about music and musicians, we can sometimes forget about the fact that we are writing about a real person—it’s easy to divorce them from their humanity. Listening to Musiq recount his early days and how he reflects on them, reminded me that these folks we write about are no different than you or me. They have struggles, demons and obstacles to overcome that they may not be aware of at the point of the creation of the art we consume and enjoy.

Listen to the Album:

Somehow hearing it straight from the horse’s mouth made it infinitely more “real” than reading about it after the fact in a David Ritz book or, even, a song’s lyrics. As the conversation developed with Questlove (and others), the background to his debut release was revealed to be a far-from-straightforward process.

Having escaped a family home that he compared to a cult, a nomadic existence ensued. Floating from one temporary solution to another, he somehow managed to get into Jazzy Jeff’s Touch Of Jazz studios where he was able to work with Carvin Haggins on a few ideas.

Fate though dealt a harsh card, with Musiq having to move to Atlanta, Georgia to find a place to stay with family down south. His determination to succeed never dried up though and so he travelled by Greyhound bus between Atlanta and Philadelphia, composing as he rode the overnight buses with just the waifs and strays of that world for company. That an album emerged at all is testament to his stubbornness and desire for self-improvement.

With all that in mind, you’d think a supreme sense of pride might be felt as the artist reminisced on his debut. But the conversation revealed a man brutally honest about his work and his (perceived) failings across the whole of his career. He talked about the need to “act and pretend like it's the greatest thing ever,” whilst explaining that he felt the songs contained upon his debut were merely sketches of “things.”

Further evidence of his humility (despite the 13 GRAMMY nominations he has earned thus far) was in his reluctance to take credit without collaborators getting theirs too. “I gotta believe it to some degree, but if you want to talk about authenticity and being genuine, I can't fully accept credit.” Perhaps the best praise for Musiq then, is in the quality of those collaborators—the people willing to put their name to a debut album by a relative unknown.

There’s a distinctly Philly outlook to those contributors. James Poyser pops up on keys and production. Leonard “Hub” Hubbard from The Roots plays bass on “Speechless” and Jill Scott arranges vocals on “Girl Next Door.” Others lending their hands to the debut include Vikter Duplaix, Eric Roberson and production duo comprised of the aforementioned Haggins and Ivan ‘Orthodox’ Barias.

The album opens with a slice of Musiq beatboxing to introduce the debut, but this is slightly misleading as what follows it is, on the whole, sweet-natured and well-balanced. For though he maintains a slight hip-hop edge to the beats and instrumentation, the lyrical content is unabashedly romantic and noticeably more respectful to women than some of his forebears and contemporaries. Indeed, on his podcast, Questlove himself called “Just Friends (Sunny)” the most “charming, platonic black anthem of all time.”

That sweetness abounds on “Girl Next Door” that features Aaries as the female protagonist in the two-sided tale of grown love with a neighborhood child friend. After the whirlwind drama of “You and Me” comes the piece de resistance that Questlove described so accurately. The effervescent “Sunny” sample does half the job, but the lyrics reveal a man concerned with his feelings for a woman he has utmost respect for: “Girl, I know this might seem strange / But let me know if I’m out of order / For stepping to you this way … And leave you with my number / And I hoped that you would call me someday / If you want you can give me yours too / And if you don’t, well I ain’t mad at you / We can still be cool.”

Watch the Official Videos:

For all that music can transform us to become (in our minds at least!) the prowling, voracious singer of lasciviousness that we may choose to listen to, this album resonated with me personally because of the respect and romance that issued from its pores. I wasn’t a “playa” and neither (did it seem) was Musiq—I could relate directly to the overriding sentiment that came from him.

As romantic one-twos go, it’s hard to imagine much beating the double whammy of “143” and “Love.” Both swell with the conviction of a true love and offer distinct thrills. For “Love” it is the effortless slide up into falsetto that takes things up several notches, whilst on “143” it is the gradual cranking up of the atmosphere to frenzy that makes it my favorite song on the album. It's a song that still resonates and sends shivers down my spine to this day.

Elsewhere there is the mid-tempo bump of “My Girl” that shines brighter than Spring sunshine and The Roots sampling “L is Gone” that draws comparison between addiction to drugs and the intoxicating high of a special relationship. Towards the end of the album, there is another doozy that successfully merges the resounding bump of a hip-hop beat and broken-hearted romanticism. “Poparatzi” has a bass line that hits the solar plexus alongside delicate plangent piano lines while Musiq works his broken heart for all its worth.

Album closer “You Be Alright” is steeped in ‘70s soul lushness and gospel affectations. From the organ’s sanctified simmering, to the false endings and restarts and the bluesy guitar licks, it wears its influences on its sleeve and is all the better for it—it is lesson in everything that is soul music. For a man who didn’t get raised in the church, there’s a lot of church going on here.

Despite this album’s success and many of those that followed, his conversation with Questlove’s crew found him expressing that artistic freedom had only come recently on his Feel The Real album from 2017. The pain of looking back at work he felt compromised by was palpable during the conversation, as was the emotional honesty and desire to do right by people. In short, the openness and integrity of this album (however he feels about it) are a true reflection of the artist today.

It may be twenty-five years since this debut was released amidst a myriad of other, more critically acclaimed albums, but Musiq Soulchild has carved out his own lane with some aplomb and stayed in the game longer and more consistently than many of those contemporaries. His determination has paid dividends.

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2020 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.