Happy 30th Anniversary to Meshell Ndegeocello’s debut album Plantation Lullabies, originally released October 19, 1993.

To call Meshell Ndegeocello’s discography prolific is gauche. Rather, she’s collected frequencies from the universe for redistribution along a 30-year continuum with a million access points to start listening.

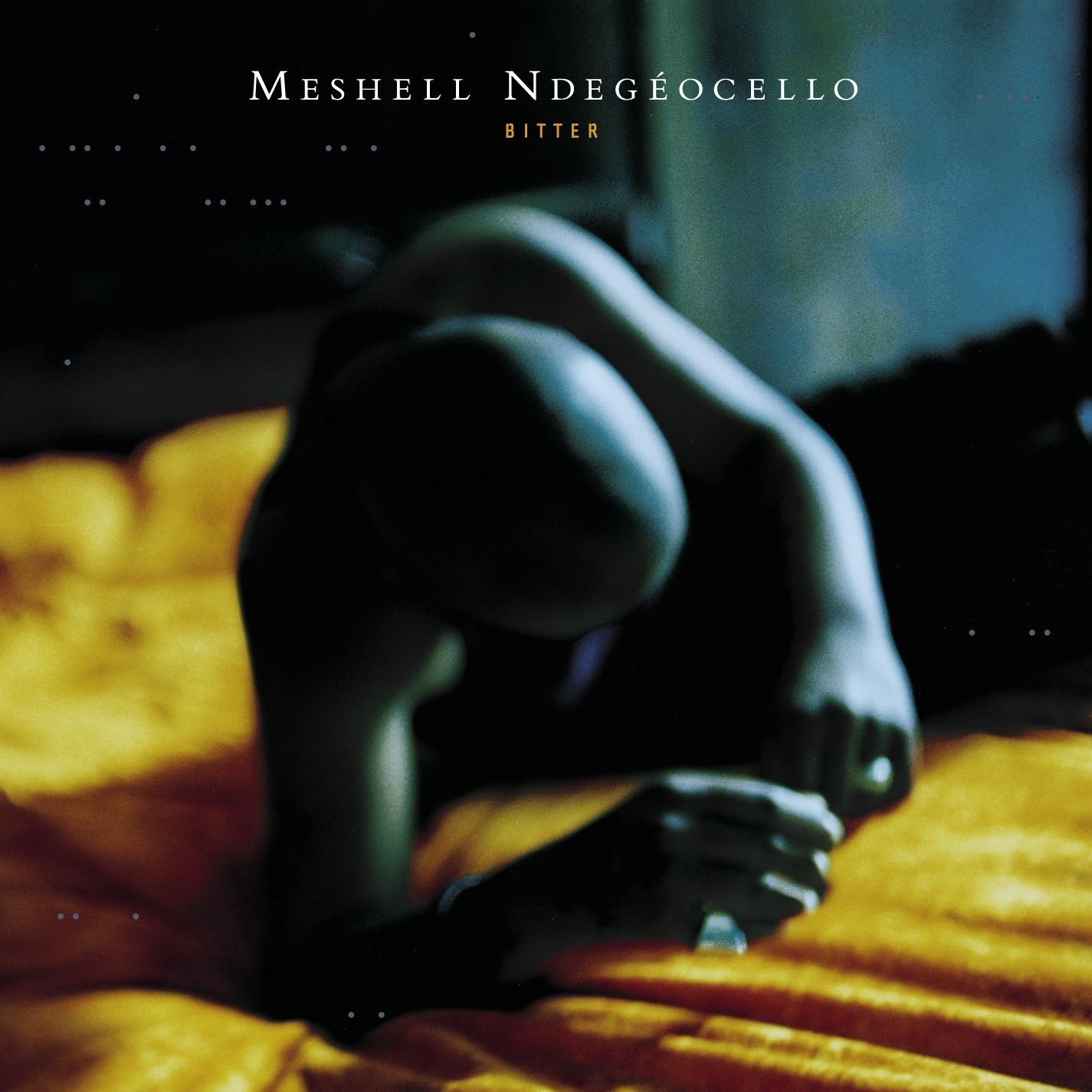

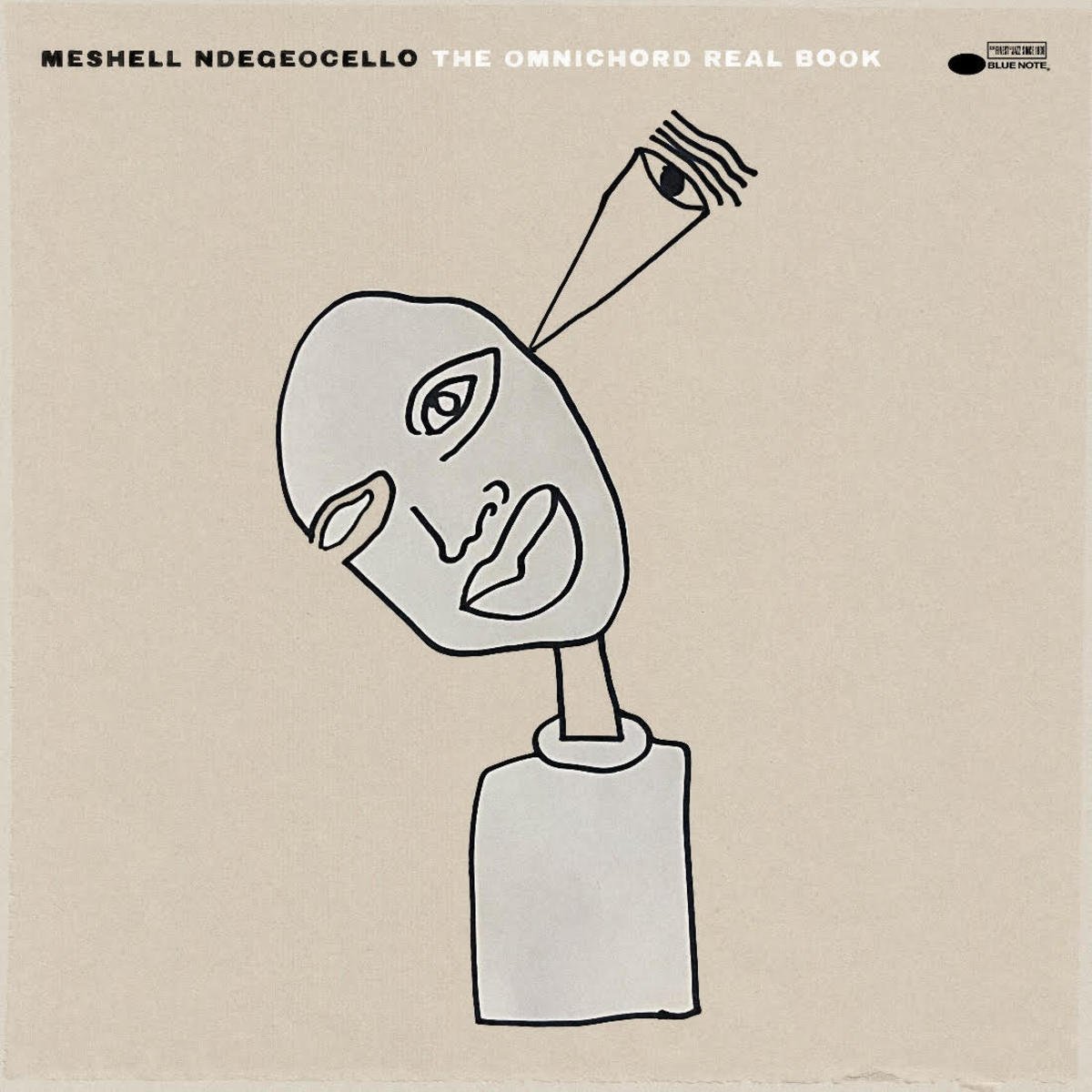

The most recent point, The Omnichord Real Book (2023), found her forging Afro-futuristic funk as if inspired by the psychedelic visuals of Everything Everywhere All at Once. With Ventriloquism (2018), she reshaped ‘80s urban radio hits into minimalist folk soul. Further back, Bitter (1999) made equal space for navel gazing and lovemaking. Before snaking her way through spacetime, one could trace her path back to a single point of origin: her stunningly colored debut Plantation Lullabies (1993). And that launch almost didn’t happen.

At a young age, she took to bass guitar, later cutting her teeth in Washington, DC’s go-go scene. Ndegeocello’s off-the-beaten-path music was initially a hard sell though. After giving birth to her son Solomon in 1989, she pitched to labels for two years. All turned her down. She was about to resign when she got a yes from Maverick Records, the Warner-distributed imprint of pop goddess Madonna.

“Vanity labels” are termed such for a reason, often inconsequential product mills that exist only to prop up their celebrity proprietor’s solipsism. Maverick, however, was aggregating exceptional talents and Ndegeocello was premier among them. Born Michelle Johnson, she adopted a Swahili surname meaning “free as a bird.” If you’ve never known how to pronounce it (in-day-gay-oh-CHEL-oh), it’s easier than it looks. Let it roll off the tongue like “indigenous fellow.”

But who is she? Why’s she bald and singing about dreadlocks? Is she gay or not? Questions like these spun the heads of those shackled to radio-sameness. For them, Ndegeocello was a rescuer, but her music was genre-averse. Is she a rapper? Does she do hip-hop? Well… yes and no to both. Like sweet potatoes versus yams, they may look alike and indeed taste similar, but they come from very different locales that make the cultivar distinct. Like its Berlin-born, New York-transplanted creator, the art simply would not settle in one place, satisfied with a neat little name.

She was the sound of intersectionality before the term reached common parlance. The public was going to have to be okay with a little bit of everything. Summarized, Plantation Lullabies is defiant hip-hop, soul fused with jazz, queer sexuality, androgyny as femininity, and fearless, boundless Blackness—converted to an audible format. Any simpler becomes reductive.

Ndegeocello produces the bulk of it with Scritti Politti-alumnus David Gamson. On the bookending tracks, she elicits help from Bob Power, and “Justify My Love” co-producer Andre Betts gets featured twice. Additionally, Ndegeocello enlists superior musicians throughout, including Luis Conte, Wah Wah Watson, James Preston, Geri Allen, Joshua Redman, and Bobby Lyle. Even DJ Premier scratches on “Two Lonely Hearts (On the Subway).” Notwithstanding this slate of servicemen, Ndegeocello is the sole songwriter on all of her record’s thirteen entries.

Listen to the Album:

Whether rapping, singing, or toggling between, her sultry voice maintains a pleasant, suede-like strength, soft to the touch, but not easily broken, even when elevating her tone to add exclamation. Her virtuoso playing however—reminiscent of Larry Graham’s though she never studied him until later in life—can be a manhandler if need arises. Like a bored, bad kid flying economy, high on sweets, Ndegeocello’s bass licks constantly kick the back of your seat. It’s an interesting weapon to wield in the landscape of ‘90s R&B.

Musically, Plantation is a savory casserole of influences. There’s always a layer of bass beneath jazz piano. Typically, jazz means “the drums will not be hitting hard,” but you’ll find rough chops of hip-hop-signifying, sampled loops, alternating with strips of analog rhythm. A liberal coating of beat poet rap threatens to dominate until it’s disguised by crumbled soul singing on top. They meld together in the heat, sometimes indistinguishable in bites.

If a lyric seems literal, scratch at its corner and see if an outer layer can be peeled away. It is at times an authoritative state-of-the-Black-disunion address; others, it is a purring celebration of overflowing sensuality. Among the dark elements, romanticism beacons through. It’s from these brighter places where the singles are harvested.

As a lead-off, “Dred Loc” seems a deceptively soft launch, until factoring in the reception of her androgyny and sexuality. In the video for this slinky rumbler with just a touch of reggae swing, she enjoys intimately touching a male lover who in turn, tenderly razors her pate clean. This and other bisexual line-crossings read as a rejection of her queer identity to some in the gay community. Per The Advocate, “Ndegeocello became the first out lesbian to be simultaneously hailed as the most musically versatile talent in years and attacked for adorning all the love songs on her debut album with masculine pronouns.”

Those pronouns get doubled down hard on “If That’s Your Boyfriend (He Wasn’t Last Night).” Though not unique as a sentiment, this aggressively funky, hip-hop clapback is effective. Purportedly inspired by some cattiness once aimed at her, nothing stops a mean-girl in her tracks like “Go ‘head / Call me what you like / While I boot-slam your boyfriend tonight.” Its achromatic art-house Jean-Baptiste Mondino clip earned MTV Video Award nominations for Best Female Video and Best New Artist in 1994.

Where both those Betts-helmed singles kicked in the door, the next became the most enduring. Exposing her vulnerable underside, “Outside Your Door” gets alarmingly sensual. Its rhythmic churn and satisfying piano line dance with each other until long after closing time.

That piano line appeared notably in Brian McKnight’s “Anytime” without so much as a passing attribution to Ndegeocello. His representative gave a thin dismissal of the similarities then, claiming “Anytime” was written “long before Meshell ever landed a recording deal” despite its copyright postdating that of “Outside Your Door” by four years. Perhaps in lieu of a proper remittance, the debt might ultimately be paid in karma.

Similar to author James Baldwin’s novel If Beale Street Could Talk, Plantation Lullabies centers Black love but not without duality. “Untitled” serves as a poetic preamble to “Step Into the Projects,” a depiction of romance against the backdrop of societal anguish. In it, the signature Meshell rap cadence moves like Gregory Hines in tap shoes, mathematical, artful, shiny, and as always, very black. Chills it gives.

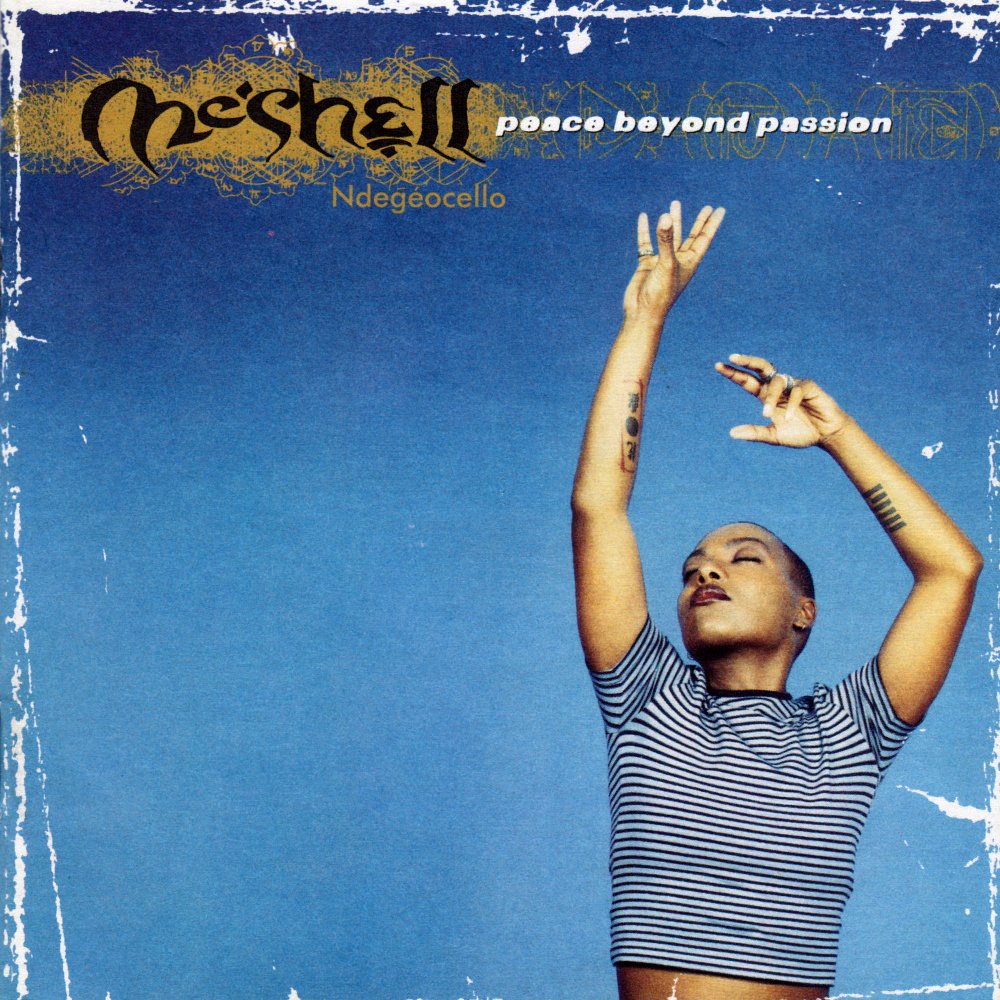

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about Meshell Ndegeocello:

There is gaiety to be found. “We do Shakespeare in our birthday suits,” she delights on “Picture Show,” a sunny day stroll with an irresistible boom-kap-ski-boom-boom-pap beat. Though US promotion wrapped with “Outside Your Door,” some international markets saw “Call Me” as a fourth single. Where its original drips syrupy sweet talk, a rare Daniel Abraham remix accessorizes it in slick, big city beats.

Plantation makes painfully astute assessment of turmoil within and without Black American culture. Framed in Motown yesteryear recollections and wailing guitar, “I’m Diggin’ You (Like an Old Soul Record)” looks back on how the civil rights movement has changed—and not necessarily for the better. The biting Curtis Mayfield-esque commentary of “Shoot’n Up and Gett’n High” likens assimilation to a controlled substance readily self-administered to blend into a hostile society.

Ndegeocello spares America no charges for the genocide of slavery and subsequent systematic oppression (“Revolution against this racist institution”). Forget Brian McKnight. When she declares, “The White man shall forever sleep with one eye open,” it is clear where the greater karmic debt resides.

This leads to a confrontational dressing down of miscegenation from a Black woman’s unsparing point of view. With justification, “Soul on Ice” violently rejects the Eurocentric beauty standards that would dismiss her allure (“Delusions of her virginal White beauty / Dancin' your head / You let the sisters go by”) and holds accountable the Black men who collude with it. “Soul on Ice” is ironically very much afire.

It is no surprise a provocateur like Madonna would champion such a jarring shock of art. Just as soul food traditions made nourishing meals of the least desirable cuts of meat, Ndegeocello makes heavy subject matter utterly delectable in a robust soup of jazz, rap, and rock. Equalized for (comparatively) painless consumption in stereo headphones, the education was free to all who wished to learn.

Critical acclaim followed and Plantation Lullabies peaked in the R&B Top 20, receiving multiple GRAMMY nominations including Best R&B Album. “If That’s Your Boyfriend” earned nods for Best R&B Song and Best Female R&B Vocal Performance as well. Apart from her own LP, Ndegeocello scored a major MTV hit with John Mellencamp, duetting on his cover of Van Morrison’s “Wild Night.” The single reached #3 Pop and garnered yet another GRAMMY consideration for Best Pop Vocal Collaboration. This momentum fueled her lunge into Peace Beyond Passion (1996), the next point in the continuum she was destined to chart.

As for Plantation Lullabies, there was no need for Ndegeocello to duplicate or revisit it. Arguably, a decade of neo soul acts—birthed through the canal Plantation pushed open—did that job for her. Blending liberally from the African diaspora of music, embracing sensuality, consciousness, and individuality with minimally requisite regard for commercial appeal? Those sound like Meshell’s children to me.

Listen: