Happy 30th Anniversary to Masta Ace Incorporated’s SlaughtaHouse, originally released May 4, 1993.

Hip-Hop music is built on conflict. I’ve written a lot about the growing acceptance of hip-hop in the mainstream in the late ’90s, the music that profited from that acceptance, and the conflict that it spawned between the commercial and underground artists. But a struggle between what’s considered popular and what’s considered “real” has been the driving force of hip-hop since Sugar Hill Gang dropped “Rapper’s Delight.”

In the case of Duval “Masta Ace” Clear, he, like many others, took issue with the hyper-violence of gangsta rap and lack of creativity he believed it was inspiring in the mid ’90s, with the landscape littered with N.W.A clones and The Chronic sound-alikes. Furthermore, he took issue with how the music was effecting people’s perception of what hip-hop should be, and disliked its influence on impressionable youth. It was this rejection of what was becoming the norm that was one of the engines of Masta Ace’s SlaughtaHouse, which was released a quarter of a century ago.

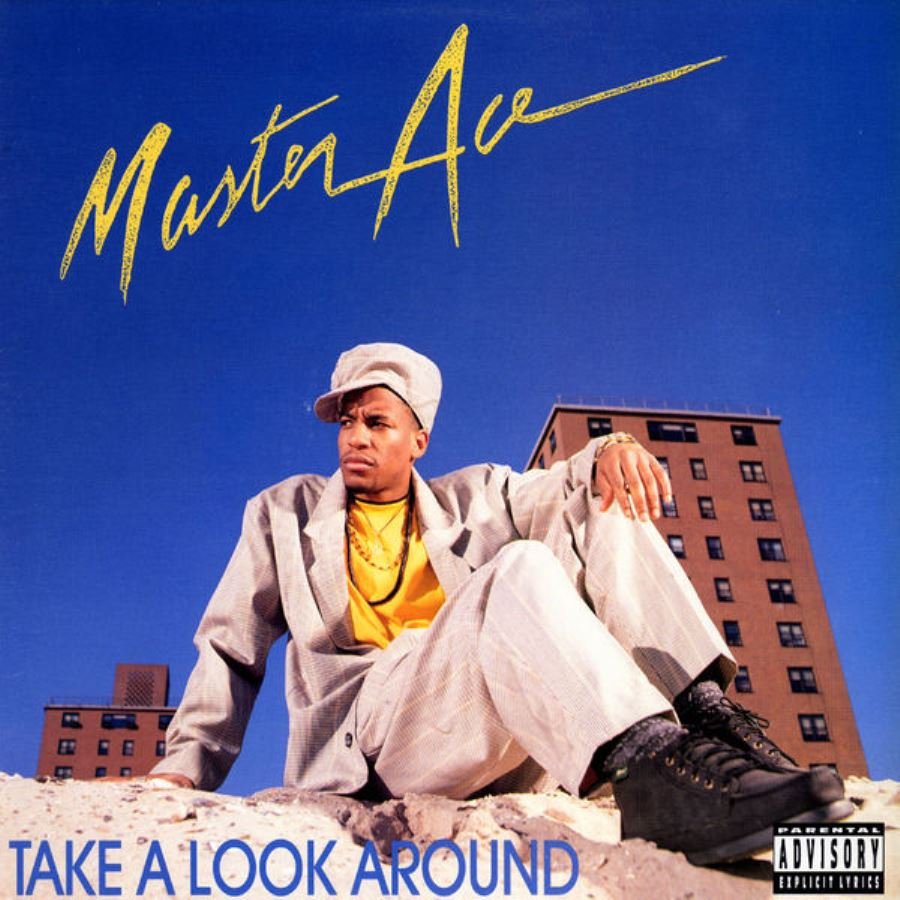

Masta Ace first received attention batting leadoff on Marley Marl’s “The Symphony,” considered by many to be the greatest posse cut of all time. He signed with Cold Chillin’/Warner Bros., and in 1990 he released his critically acclaimed and reasonably successful debut album Take a Look Around. It was a dope and worthy first effort, but in 1991, Warner Bros. cut him from the roster due to budgetary reasons. As a result, he was left with an incomplete second album and no record label.

Ace soon signed with Los Angeles-based label Delicious Vinyl, at the time best known for being the home of artists like Tone Loc and Young MC. He made his first appearance with the label on the Brand New Heavies’ Heavy Rhyme Experience (1992), contributing the banger “Wake Me When I’m Dead.” He soon set about recording his sophomore album, mostly starting from scratch, as Warner Bros. still owned the shelved material he’d already recorded.

The result was SlaughtaHouse, in some ways in keeping with the spirit of his previous material, and in other ways a solid step in a new direction. On Take a Look Around, Ace had recorded party jams, lyrical displays, and social commentary. That same balance in subject matter remains on SlaughtaHouse, but the overall feel of the album is much different. Everything seemed darker, grimier, and grittier this time around. Furthermore, Ace has said he was much angrier while recording this album. Angry at the state of hip-hop and angry at how things had ended with Cold Chillin’/Warner Bros., and it showed in his lyrics and demeanor.

Another major change that Ace went through regarded his crew. For his first album, he was affiliated with Marley Marl and the Juice Crew. Marley handled much of the production on Take a Look Around and Ace would rhyme and tour with artists like Craig G and Big Daddy Kane. All of that changed on SlaughtaHouse, as Ace pieced together a new crew he appropriately dubbed Masta Ace Incorporated. He re-positioned himself as Ase One, and enlisted a talented yet largely unknown roster of emcees and producers that included Lord Digga, EyceURock (Eyce, Uneek, and Rokkdiesel), Paula Perry, Latief, and The Witchdoc.

The shifts in tone and affiliation paid off. While Take a Look Around was a strong album, SlaughtaHouse was a marked improvement. It’s one of the best albums of 1993, absolutely one of the strongest hip-hop albums from the ’90s, and arguably in the upper echelon of the greatest hip-hop albums of all time.

Listen to the Album:

Ace targets the proliferation of gangsta rap music and its mentality right off the bat, starting with the title track. The song begins with a skit set in a classroom, where the teacher, in the midst of teaching “Hardcore Rap 101,” emphasizes to his grade school age students to make sure that they mention that they smoke blunts and drink 40 ozs, and to always “act like they have a gun” when rhyming.

The song itself is split into two parts. The first half is a parody of a gangsta rap track, featuring “MC Negro” and “The Ig’nant MC.” The two deliver the most stereotypically violent and boorish lyrics possible, chanting “Murda murda murda, and kill kill kill!” over samples of “More Bounce to the Ounce” and “Funky Worm.” The second half of the song features Ace putting together the nominal slaughterhouse for these wack and clichéd emcees, promising these fake gangstas blood-soaked deaths for their transgressions. It’s grimly funny and perfectly executed.

The subject matter on SlaughtaHouse is not limited to mocking derivative gangsta rap. Ace dedicates much of the album to presenting an alternative to the cartoonish depictions of violence and street life. Ace tackles the psychological effects of living in a community consumed by violence on “Late Model Sedan.” He vents his frustrations about not feeling a sense of security while in the neighborhood where he was born and raised, scared to leave his home using the front door, lest he becomes a victim of a raging turf battle. He laments the proliferation of guns in the area, rapping, “How many kids get shot talking that ‘Throw up your hands’ shit / And fight like a man, but he don't get to land shit / Not one punch, the only hit was when his head hit the concrete / Got knocked clean off his feet.”

Ace displays his superior storytelling ability on “Jack B. Nimble,” a gangsta fairytale of a different sort. Ace plays the narrator, recounting the final minutes of the eponymous Jack. The story begins in medias res, with Jack fleeing hordes of crooked police officers, desperately looking for safe harbor somewhere in his neighborhood. He frantically searches for a hiding place, regretting threatening to report those cops who allowed him to sell drugs in the neighborhood.

Ace continues to use humor throughout the album, particularly on “Who U Jackin’?” his duet with Paula Perry. Produced by the Bluez Brothers (Lord Digga and Witchdoc), it’s an adversarial male vs. female song in the spirit of Ice Cube and Yo-Yo’s collaboration on “It’s a Man’s World.” The song has a unique spin to it, with Ace playing the role of a cocky stick-up kid and Perry as a street-savvy Brooklyn resident. Over a loop of Galt McDermott’s “Harlem Medley,” Ace attempts to stick Perry for her jewels, only to have Perry turn the tables on him with a little help from her concealed razor.

Ace also cuts loose a bit on “Jeep Ass Niguh,” SlaughtaHouse’s first single, a dedication to his love of playing hip-hop out of his jeep at exceedingly high volumes. Over another Bluez Brothers produced track, Ace raps over blaring horns as well as the rumbling bassline sampled from George Benson’s version of “California Dreaming.” He describes a roll through the streets of Brooklyn in his jeep, blasting A Tribe Called Quest’s The Low End Theory (1991), challenging rival cars and police officers alike to sound system battles.

Ace also engages in a good number of lyrical demonstrations on SlaughtaHouse. He frequently utilizes his “On Beat/Off Beat” style throughout these types of tracks, purposely falling off beat and then sliding back to effortless at will. Tracks like the jazzy “Mad Wunz” or the bouncy “Ain’t Tha Masta?” are more upbeat. But Ace really excels when his sound veers towards a more sinister atmosphere.

One example is “Big East,” one of the finest songs on the album. Here Ace rhymes over a beat created by Connecticut’s The Beatheads, consisting of a bare-bones drum track and a loop of the intro guitar solo of Earth, Wind & Fire’s “Handwriting on the Wall.” Ace utilizes a slower flow, letting the syllables and phrases ooze over the track. He raps, “I'm hitting ’em over the head with lyrical styles like a bottle / My foot’s on the pedal, my hand is on the throttle.”

“Style Wars,” produced by Ace himself, maintains the ominous feel, bolstered by a magnificent chop of B.B. King’s “The Thrill is Gone,” as he trades rhymes with Lord Digga. Digga, with his imposing baritone and robust delivery, shines throughout the album, providing ad-libs, performing the choruses on various tracks, and dropping thorough verses on track like “Style Wars” and the slippery “Crazy Drunken Style.”

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about Masta Ace:

The album ends with “Saturday Night Live,” a posse cut featuring various members of Masta Ace Incorporated. Ace is joined by Digga, Eyce, and Uneek (who also produced the song), to romp over a flip of Melvin Bliss’ “Synthetic Substitution.” All four emcees contribute boisterous verses, but Digga shines the brightest as the self-described “the microphone mutilator / With the hardcore data to mash motherfuckers like potatoes / I dare a little punk to try to diss me / You wanna know why? ’Cause I spit on spectators.” The song features scratches by an uncredited DJ Premier, who uses his hand skills to cut a line from Big Daddy Kane’s “Get Into It” with precision.

Though Ace expresses a good deal of anger throughout SlaughtaHouse, he also attempted to lead by example. He presented his thoughts on bringing unity to the Black community and re-elevated his game as an artist, providing an exceptional musical alternative to what was being presented in the mainstream.

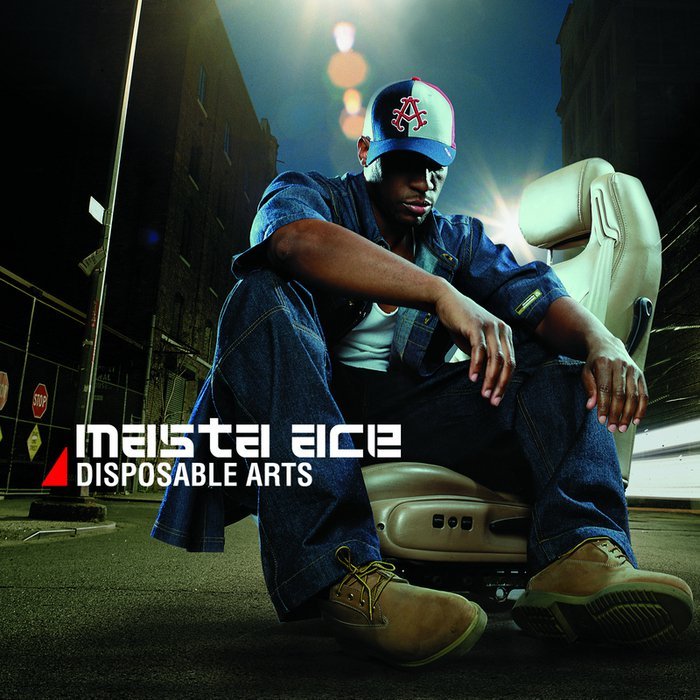

Ace continued on this same path throughout his career, even when further re-dedicating himself towards creating East Coast rider music on his follow-up album Sittin’ On Chrome (1995). Then after a half-decade hiatus, Ace had one of the great career resurgences beginning in the ’00s, which continues today. And even now, though he’s progressed even further as an artist, Ace carries with him the ethos that he expressed on SlaughtaHouse. And hip-hop music is better off for it.

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2018 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.