Happy 45th Anniversary to Marvin Gaye’s fifteenth studio album Here, My Dear, originally released December 15, 1978.

Soul music, by its very name and definition, should mine every nook, cranny and secretive corner of the human condition. Unvarnished, raw and ugly with no stone left unturned, it reveals the pain, heartache and occasional joys of the human spirit.

Though history bulges with great soul albums, few—if any—reach the darkest, secluded recesses of the soul in the way that Marvin Gaye’s Here, My Dear does. Released in December 1978, it was his fifteenth studio album and followed a winning run that has few parallels in musical history.

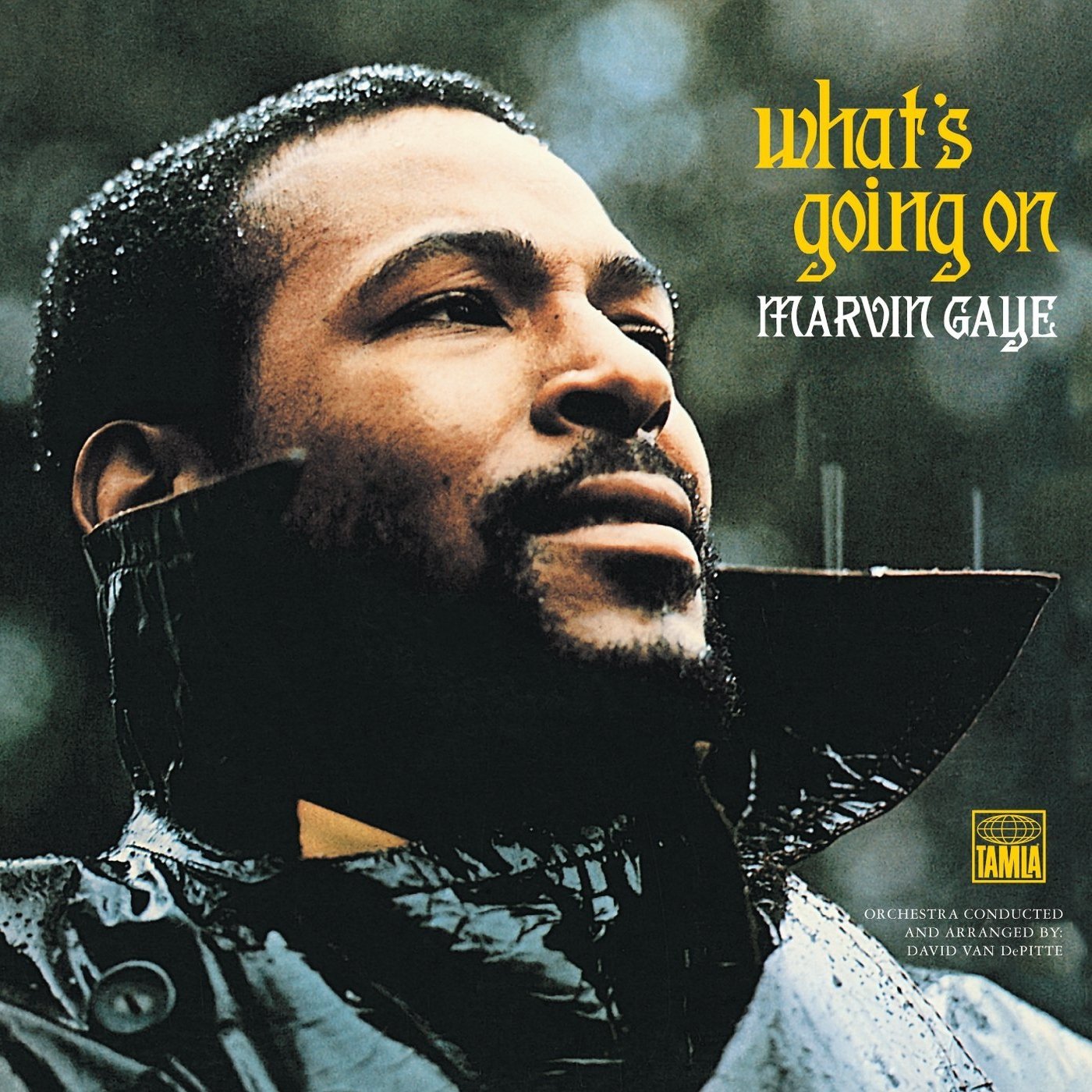

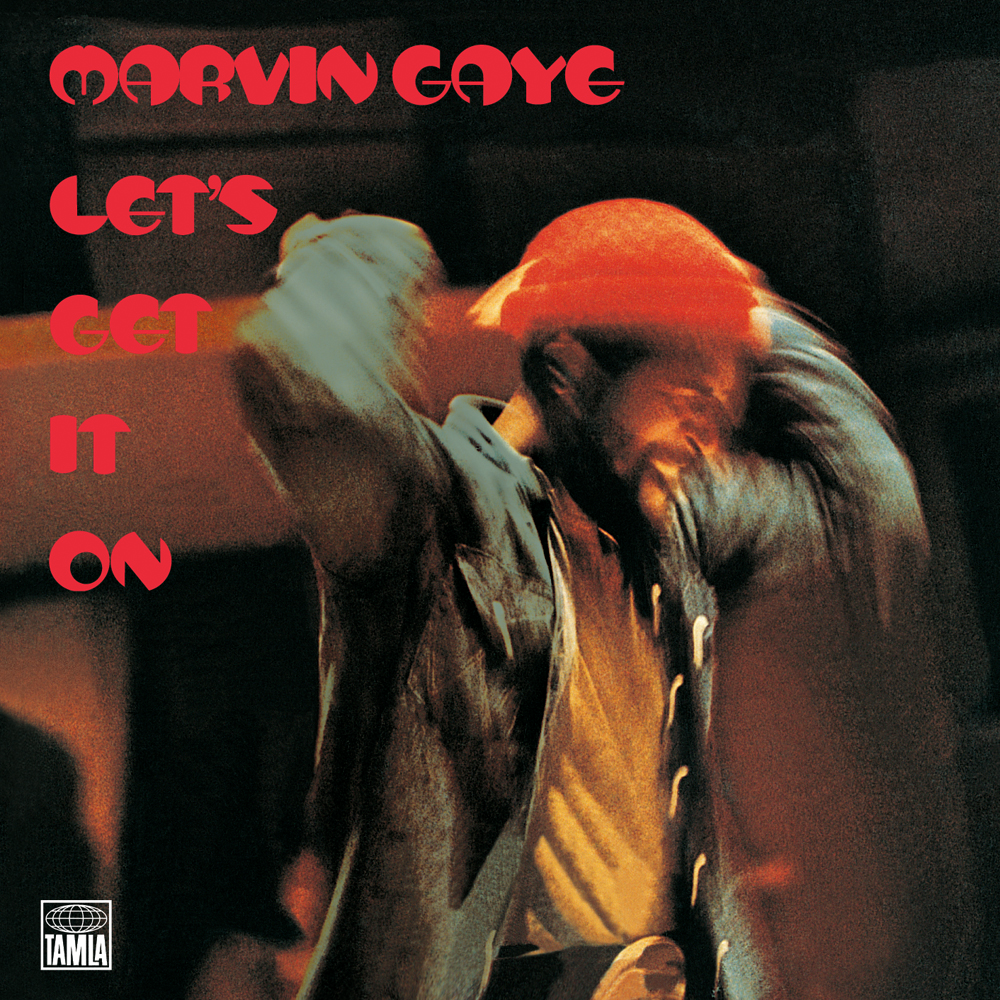

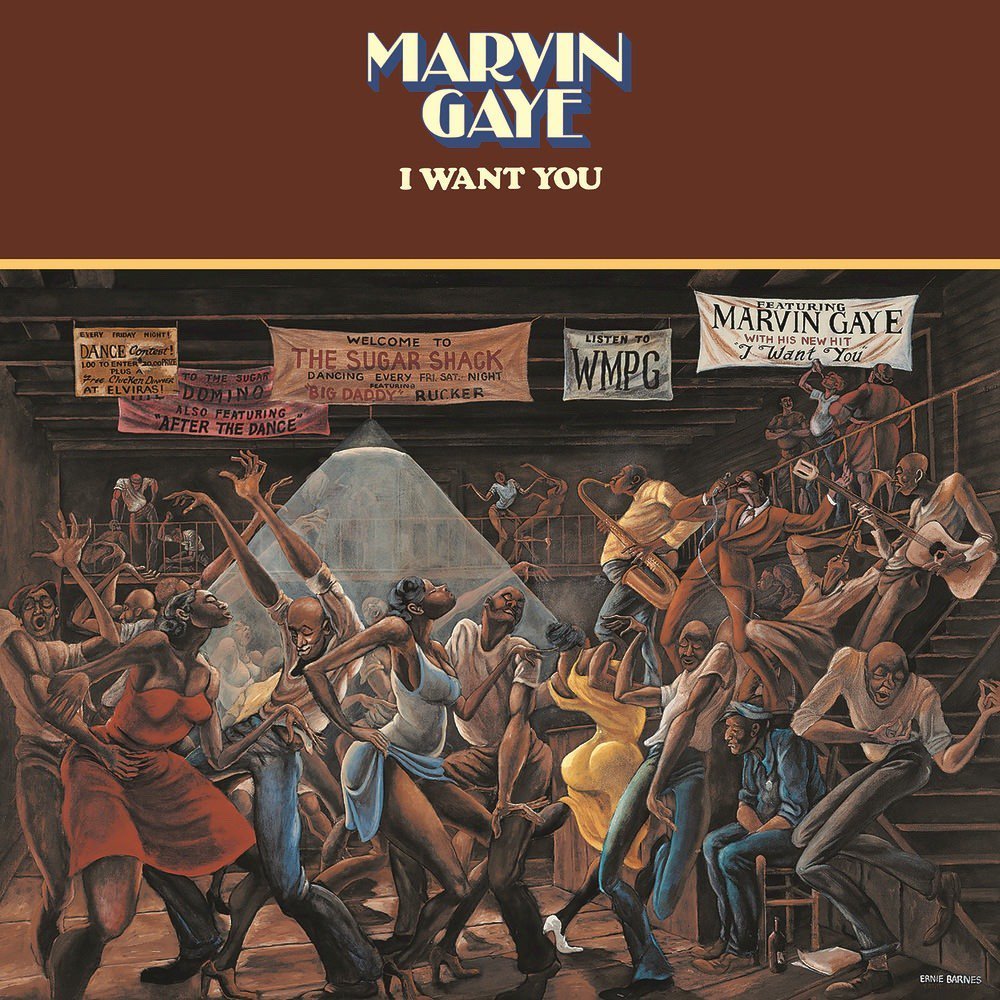

1971 saw him change the face of Motown and soul music in general with the sanctified masterpiece What’s Going On. 1973 brought the equally masterful, but totally unholy Let’s Get It On. And 1976 produced the stunning, erotic ode to Janis Hunter (of whom there will be more later) that is I Want You.

Here, My Dear saw that run come to a screeching halt. Record buyers and critics shunned it, deeming it weird and inaccessible. And they had a point. Even now, 45 years later, it lives up to both of those epithets if the listener isn’t prepared to dive to the depths of despair to the accompaniment of Marvin Gaye’s peerless voice.

To say Gaye was in a hole at this point in his life would be a gargantuan understatement—it was a meteor-sized bombsite of a hole, brought on by his own personal demons and encouraged further by copious amounts of most available illicit substances. And right there, at the epicenter of the bomb blast, was his marriage to Anna Gordy Gaye—a marriage that was decaying like road-kill in the autumn. It was slow and ugly.

In November of 1975, the long, slow death throes of the marriage had reached their conclusion—Anna filed for divorce citing irreconcilable differences. By autumn of 1976, things had plummeted to the point where a warrant for Gaye’s arrest (for non-payment of alimony) was issued. The ignominy of being unable to support his son (Marvin Gaye III) drove further resentment to the darkest corners of Gaye’s heart and what was an already toxic relationship, somehow managed to plumb new depths of enmity.

With no end in sight, Gaye’s attorney (Curtis Shaw) tabled an unusual plan to finally end the interminable process of separation. He suggested that the next album would see Anna receive 50% of the royalties. It made sense. After all, he’d just had a major hit with “Got To Give It Up.” However given Gaye’s complicated psyche, it was never going to be that straightforward.

Listen to the Album:

At first, Gaye imagined an album as cursory gesture—a willingly disdainful failure of artistry designed to be the ultimate “fuck you” to the woman who (to his mind anyway) had mangled his heart. However, as he dwelt on the idea longer, he began to consider making Anna the heart of a concept album about the life and slow death of their relationship.

There were those who thought the relationship was one of—at least to some extent—convenience. In 1964, when Gaye married his boss’s sister Anna, his career was beginning to lift off to new places, but having Berry Gordy’s sister as his wife couldn’t exactly hurt his career. Anna, meanwhile, would become the wife of a star and receive all the trappings that this would bestow upon her. From such rocky foundations sprang jealousy and infidelity.

Throw in an unhealthy dose of Gaye’s oedipal complex, a fully unreconstructed chauvinist attitude to women and the wealth, adulation and drugs that came with success and it wouldn’t have taken a detective to see how the marriage would pan out. Which explains why a “warts and all,” “air your dirty laundry in public” and “get it all of your chest” approach paid such creative dividends (even if they came posthumously, a handful of years removed from the album’s release).

In listening to Here, My Dear 45 years later, the sheer, unadulterated honesty cuts like a double-edged sword. For all the artistic integrity in mining the heartache and pain, there is the odd splash of self-pity and sniveling wounded male ego. It’s there on the central and recurring theme “When Did You Stop Loving Me, When Did I Stop Loving You”—having the bare-faced cheek to sing, “If you ever loved me with all of your heart / You’d never take a million dollars to part” whilst setting up home with Janis Hunter and having two children while still married to Anna, is the work of a “special” kind of man.

Those misgivings aside, isn’t truth what great art is all about though? This may be an ugly and flawed truth, but it is his truth and it is set to such a supreme musical backdrop that it stands as the equal of anything he recorded. The album is a gaping wound of shattered pride to the soundtrack of the sweetest soul music and this contrast is magical.

At 73 minutes long, it dwarfs his previous masterpieces and it seems only fitting that it does. Just as the marriage was a slow, sustained dive to oblivion, so the album simmers just below boiling point, content to release the anger and frustrations of married life in sporadic bursts across the extended running time. Indeed, one of those moments is as perfect a moment as you will find anywhere in soul music.

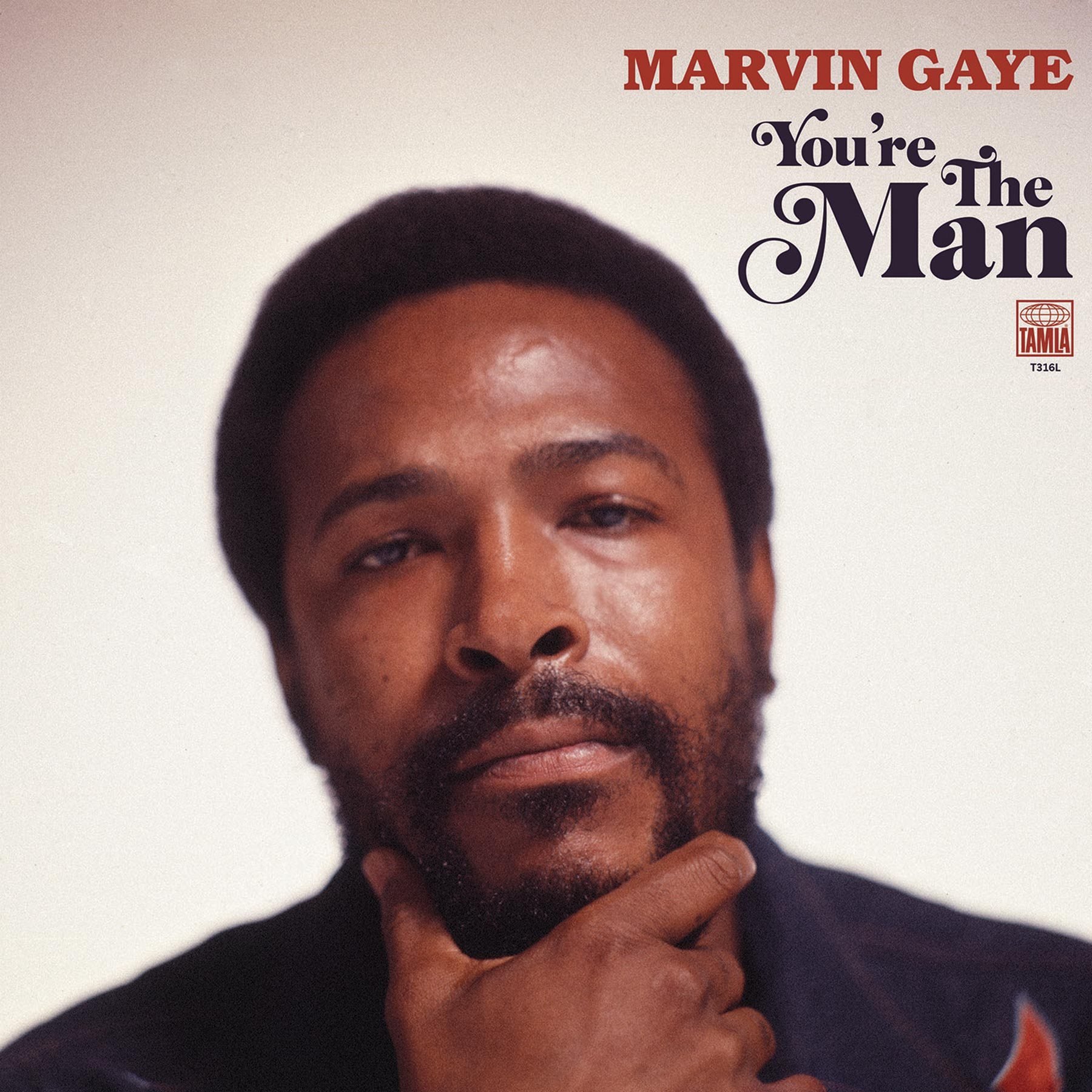

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about Marvin Gaye:

In the midst of the delicate and loosely structured “Anna’s Song,” he lets out three calls of Anna’s name, each one communicating a different emotion with the single word. The third of those is a plaintive, primal plea that somehow manages to convey loneliness, heartache, anger and despair all within a few heartbeats. It is quite astonishing.

The musical palette is mainly populated by the same smooth, sensual soul sounds that dominated I Want You and Let’s Get It On, and at times it feels as if songs bleed into one another to create an extended stream of musical consciousness. Breaking those grooves are a nod to Gaye’s earliest musical stylings—the doo-wop inspired title track and opener “Here My Dear” and a strutting, futuristic re-imagining of his and Anna’s relationship on “A Funky Space Reincarnation.”

It always seems churlish to me to pick out songs from the album for the simple fact that it belongs together as a whole, in the sequence it was laid to wax. But what would a tribute be without mentioning the two standout cuts from this momentous album?

The aforementioned “When Did You Stop Loving Me, When Did I Stop Loving You” shines as the centerpiece of the album, coming as it does, with a reprise towards the end of the album. It sums up the relationship with a mix of fragile and wounded male ego, bitterness, resentment and reminiscence of times well spent together. Not only does it summarize the relationship’s multi-faceted nature, it demonstrates Gaye’s voice in all its heavenly glory.

His voice was always capable of expressing strength and vulnerability at the same time, but here, on his grief-stricken tour-de-force, he seems capable of bristling with hubris and being torn down and broken in the same breath. Then there is the imperious vocal layering that is one of his hallmarks. If one Marvin can shake you to the core, imagine what a celestial choir of Marvins can do. Perfection.

An unequivocally bitter and candid portrait of their relationship, “You Can Leave But Its Going To Cost You” is the other of the twin pillars of confessional brilliance that underpin the album. In between bouts of revealing Anna’s own demons (“Sometimes your eyes was red as fire / Intoxicated”), Gaye finds time to reflect on the battle that was dragging them both through the courts to the tune of his twisted triumphalism, when he sings, “You tried to have them shackle me / Bring me in / Tell me what for / So I’d satisfy you baby / You have won the battle / Oh but Daddy’s gonna win the war.”

That the album finishes (excepting a reprise of “WDYSLMWDISLY”) with a decidedly positive and upbeat “Falling In Love Again” is a surprise given the animosity and bile that precedes it. Yet it predictably brings a tinge of sadness to proceedings as this feted new love with Janis Hunter would be over before it had barely begun.

By the time the record was actually released in December of 1978, the blossoming new love had gone the same way as that with Anna, albeit much more quickly. David Ritz said it best in the liner notes for the reissued album in 1994: “When it came to dealing with women, Marvin had a gift for making himself miserable.”

Luckily for us though, that misery has never sounded as good as it did here. Mining the depths of his soul for our edification, he sacrificed his sanity so that we could regain some of ours through his extraordinary gift.

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2018 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.