Happy 30th Anniversary to Ice Cube’s fourth studio album Lethal Injection, originally released December 7, 1993.

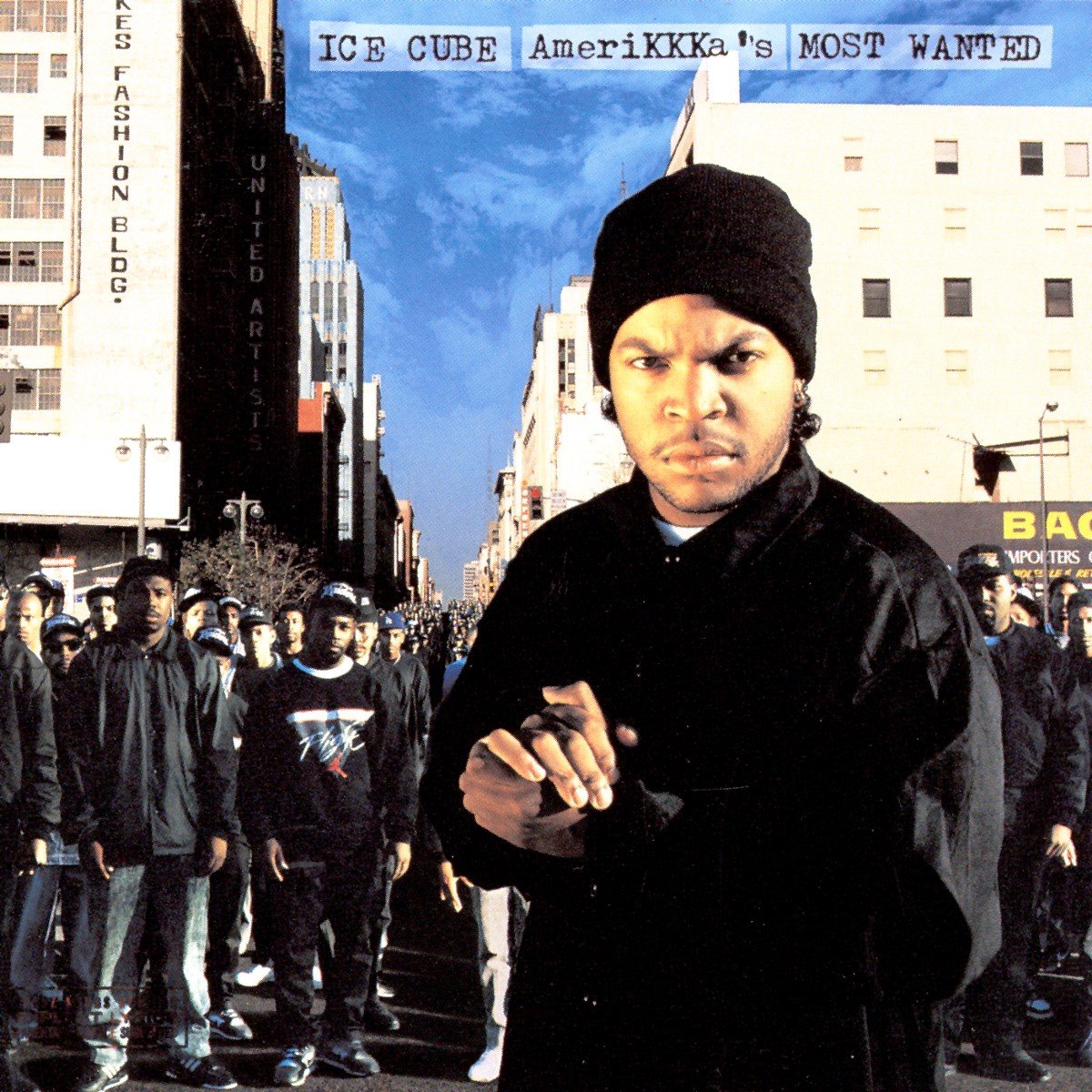

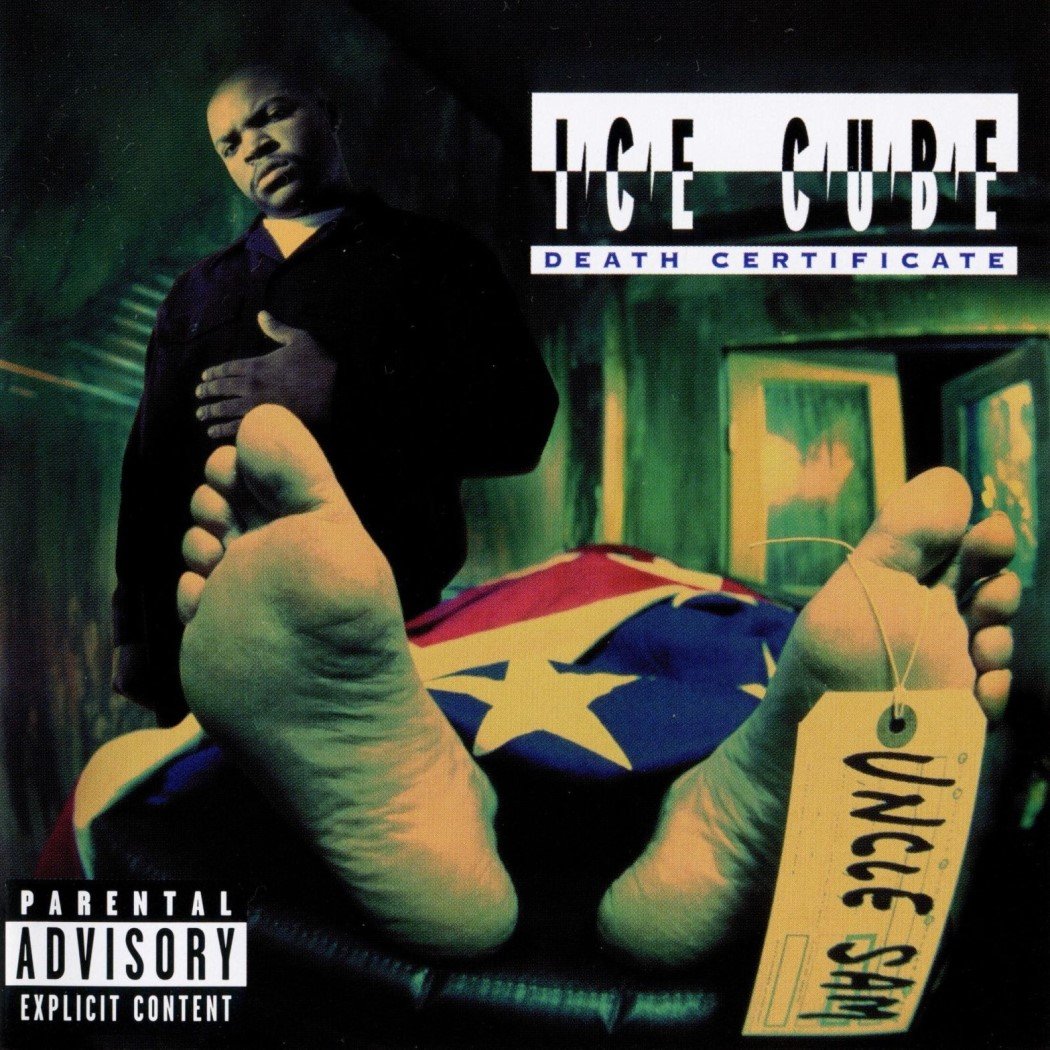

O’Shea “Ice Cube” Jackson kicked off his solo career with a helluva run. It included five releases spanning a three-and-a-half-year period, including four full lengths. Some of these projects, like AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted (1990) and Death Certificate (1991), are rightly considered among the greatest albums of all time. All of the endeavors captured the zeitgeist of the time, and function as the raw, no punches pulled diaries of young Black men in the United States struggling to stay above ground.

The final entry of this reign was Lethal Injection, released 30 years ago. Comparatively speaking, it’s the weakest entry of Cube’s initial full lengths. Cube had set an impossibly high standard with his previous releases and Lethal Injection doesn’t quite rise to the heights of greatness that his audience expected of him. However, it was still a commercial success, as it’s certified Platinum and still features some very potent and memorable entries in Cube’s discography. The South Central LA-based emcee revised his approach, but still remained true to himself.

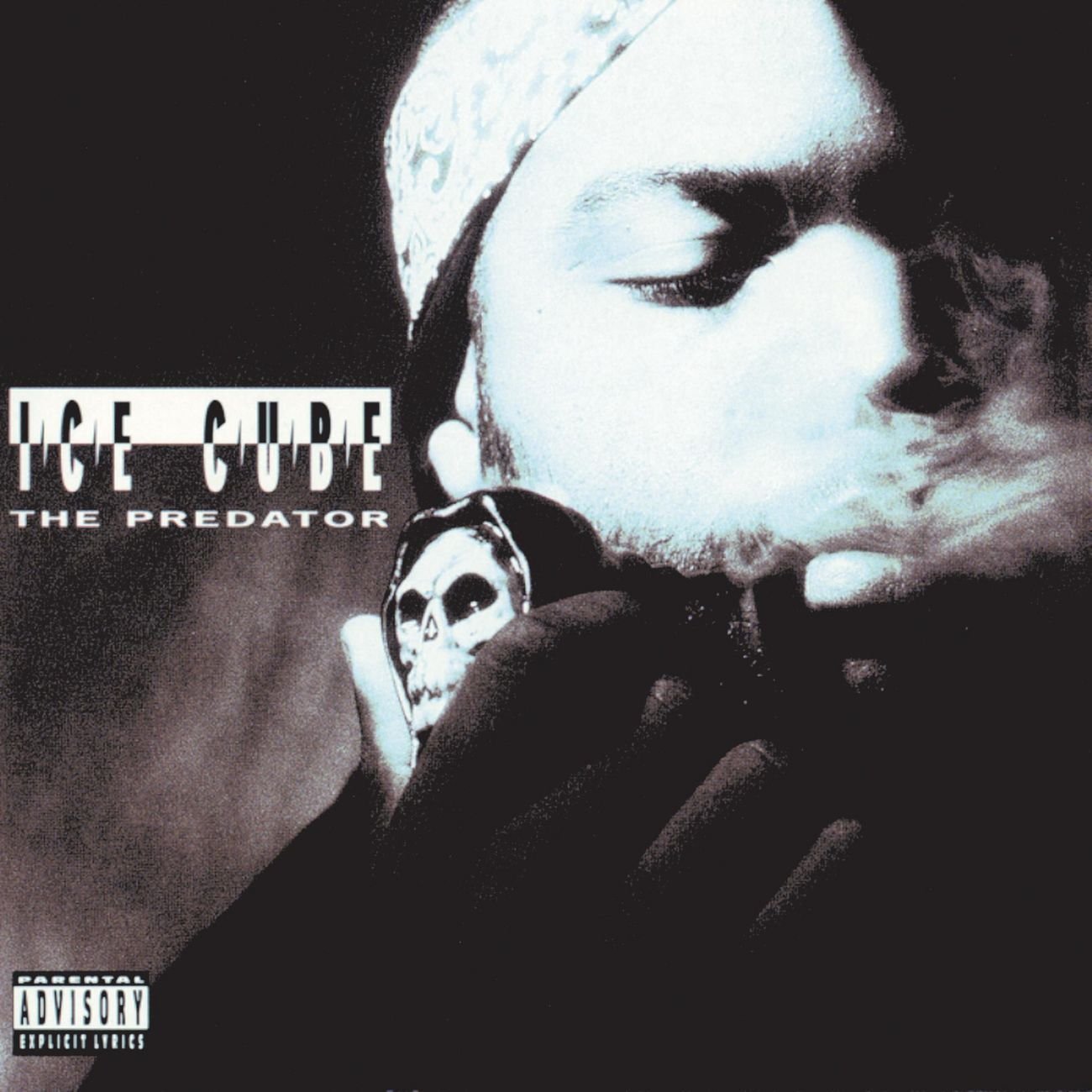

Cube had been adjusting his rhyme style on The Predator (1992), his previous album. He’d simplified things, moving from a more complex to a slower, straight-forward delivery. It was occasionally not my particular cup of tea, but I couldn’t argue with its success. Cube’s more simplified approach to rhyming made his personality on record more relatable when necessary.

The beats on Lethal Injection sound unlike anything that Cube had featured on his previous projects. This owes to the fact that Cube works with a completely different slate of producers than those he teamed with on his first three albums, forgoing beat-smiths like The Boogie Men, The Bomb Squad, and DJ Muggs. QDIII is the album’s musical MVP, hooking up many of the album’s best tracks. The son of the legendary Quincy Jones had worked with Cube’s camp on Yo-Yo’s You Better Ask Somebody (1993) and continued their partnership. Cube also has chemistry with O.G. Laylaw, as well as Danish production team Madness 4 Real. Others, such as Brian G and the 88 X Unit team, have mixed success.

“Bop Gun (One Nation),” one of the album’s early singles, was not particularly well received. The party-oriented track doesn’t lack for ambition, as producer QDIII meticulously recreates the main groove of Funkadelic’s “One Nation Under a Groove,” one of the funk group’s most beloved and iconic recordings. Cube and QDIII also enlist George Clinton, then in the midst of his career relaunch, to croon the song’s more memorable portions.

Watch the Official Videos:

For such a largely inoffensive undertaking, it's a bit odd that the song was roundly rejected by portions of Cube’s fanbase. It’s not like rapping over a Funkadelic sample was something alien to the South Central rapper. Maybe the issue was the song’s length; the album version exceeds 11 minutes, while the single version clocks in at over five. Cube’s verses aren’t particularly creative, as he strings together references to sing titles and lyrics from the Funkadelic/Parliament/Clinton library, as well as other funk jams from the 1970s and early 1980s. It’s also possible Cube’s audience was hesitant to accept a party-oriented track from a rapper who’d made his name recording street-themed, politically charged hip-hop.

For what it’s worth, “Bop Gun” is one of the very few tracks where Cube keeps things light. Much of the rest of the album is as deadly serious, inflammatory, and aggressive as what appeared on Death Certificate and The Predator. Cube is in full-on street soldier mode on “Really Doe,” a menacing entry produced by the aforementioned Laylaw and Derrick McDowell. Cube stalks through the track, “living unforgiven with the mic on,” unafraid to confront police officers and other shit-starters. On the song’s second verse, he describes navigating a 30-day stint in county jail, making do in nearly unlivable conditions and contending with belligerent correctional officers.

One of the other frequent complaints about Lethal Injection is that Cube began to utilize the G-Funk styled production. This musical style was popularized by Dr. Dre’s The Chronic (1992), which then began influencing hip-hop production as a whole. QDIII in particular crafts G-Funk tracks but does an outstanding job in doing so. In fact, Lethal Injection features two of the best G-Funk tracks that didn’t come out of Dre’s or the group Above the Law’s camp.

The first is “Ghetto Bird,” which serves as a screed against the omnipresent police helicopters that roamed the night skies over economically depressed communities in Los Angeles. When not fantasizing of downing one of these mechanical buzzards with a rocket launcher, Cube spins a scenario where he seeks to escape the scavenger. He describes furiously traversing the greater Los Angeles area, first behind the wheel of a stolen car, then scrambling through the darkened streets on foot. It’s one of the album’s strongest narratives.

The overall strongest story rap is “What Can I Do?” Cube has always excelled at weaving detailed, first-person accounts of the highs and lows of engaging in criminal behavior. The song serves as a somewhat telescoped version of Death Certificate’s “My Summer Vacation,” as Cube chronicles his rise from street dealer to drug kingpin doing business in Minnesota with “a house next to Prince, so now I can kick it.” Though Cube is eventually arrested by the feds, the song goes beyond his incarceration, delving into his strained attempts to reintegrate into society, reduced to working at McDonald’s in order to make ends meet.

However, Cube explicitly spells out that the point of the song isn’t that crime doesn’t pay; it’s the United States as a whole is failing the Black population. He explains how this country perpetuates a system where the youth are not given the skills or opportunities to better themselves and support their families, and thus are forced to turn toward illegal means.

Unfortunately, the production on “What Can I Do?” doesn’t quite live up to Cube’s effort on the mic. Fortunately, the song received a much-needed remix by the aforementioned Derrick McDowell and Laylaw. The album version “Lil’ Ass Gee” has similar production issues, as Cube’s description of the murderous ruthlessness of teenagers conditioned to believe that their lives have no value is hampered by a cluttered track. The “Gumbo Funk” remix by N.O. Joe would give the song new life.

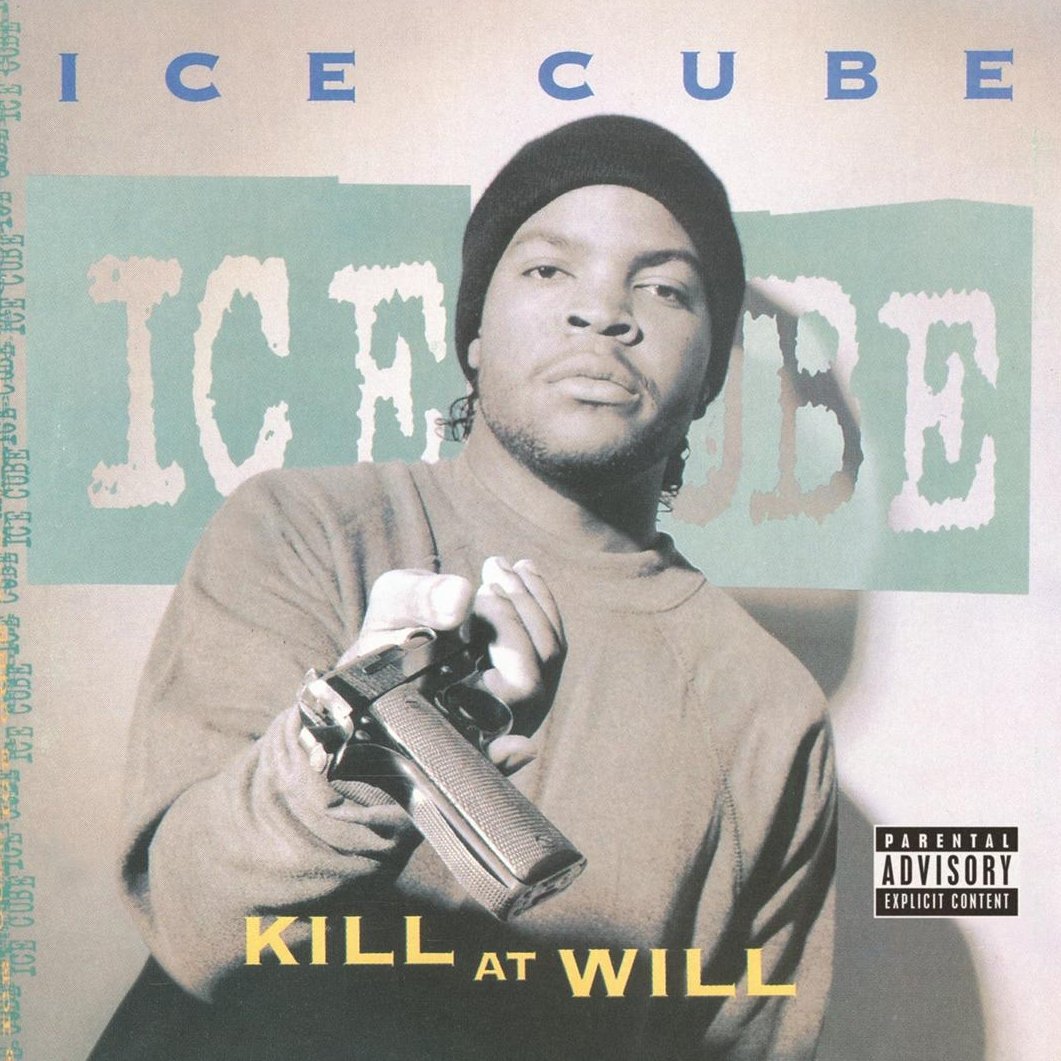

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about Ice Cube:

Overall, many of Lethal Injection’s strongest tracks are the slower-paced entries. “You Know How We Do It,” the album’s third single, is a perfect piece of rider music and the album’s other outstanding G-Funk infused song. QDIII is masterful behind the boards, combining a replay of Evelyn “Champagne” King’s “The Show is Over” with squealing synths inspired by Kool & the Gang’s “Summer Madness.” Like many of the best G-Funk tracks, Cube focuses his verses on rolling across Los Angeles’ asphalt arteries, conversating with his friends and looking to get into a little bit of trouble.

“Make It Smooth, Make It Rough” is an adept exercise that demonstrates how two emcees can take two distinct approaches to a track and have both work. The QDIII-produced song is a duet with Cube and K-Dee, part of Da Lench Mob collective and original member of Cube’s first group, C.I.A. (f.k.a. Stereo Crew). The two trade bars and short verses, with K-Dee’s laid-back approach contrasting well with Cube’s blunt delivery.

Madness 4 Real slows things to an absolute crawl on “Down 4 Whatever,” one of the most unique recordings in Cube’s discography. Cube matches the song’s tempo with his creeping drawl, muses about his pursuit of the opposite sex and reminisces about his father’s drunken exploits. Some years later, the song would be used to excellent effect in the film Office Space (1999).

Cube closes Lethal Injection with a pair of songs full of equal parts contempt and revolutionary zeal. “Enemy” functions as a rejection of non-violence as a means to combat racism in the United States, instead endorsing a militant call to arms. Over a funk-filled guitar and horn samples, he envisions a blood-soaked revolution in 1995, where the Black population rises up against the “Devils” in control to achieve some justice.

“When I Get To Heaven” isn’t outwardly violent but is every bit a screed against oppressors in the Black community. Cube vociferously discards what he sees as a passive form of spirituality in the form of Christianity as outlined in the King James version of the Bible. He mocks the surface-level, capitalistic nature of many churches and the “Waiting on the Lord!” version of salvation, pondering, “So Mr. Preacher, if I couldn’t pay my tithe, will I have to wait outside?”

Cube took a hiatus from his solo career after Lethal Injection, not releasing another album of original solo material for close to five years. In between, he put out the Bootlegs & B-Sides (1995) compilation and started recording with an expanding roster of artists. His most prominent project during this period was the self-titled debut from Westside Connection, a three-emcee supergroup featuring himself, WC, and Mack 10.

Mostly though, Cube acted. He cultivated his career on the big screen, hoping to appeal to established fans and a new audience as a movie star. It worked, as many today are more familiar with him as the star of films like Friday and the Ride Along series than as an emcee.

Though Cube eventually re-assumed his solo career, nothing he released since has been as good as Lethal Injection. Though his passion and anger have gone unmodulated as the last three decades have passed, he rarely seems interested into channeling it into his solo material. As a capper to an impressive run, Lethal Injection succeeds in showing that Cube’s fervor still ran as hot as ever, even as he modified his focus on the means by which his fans would consume his art.

Listen: