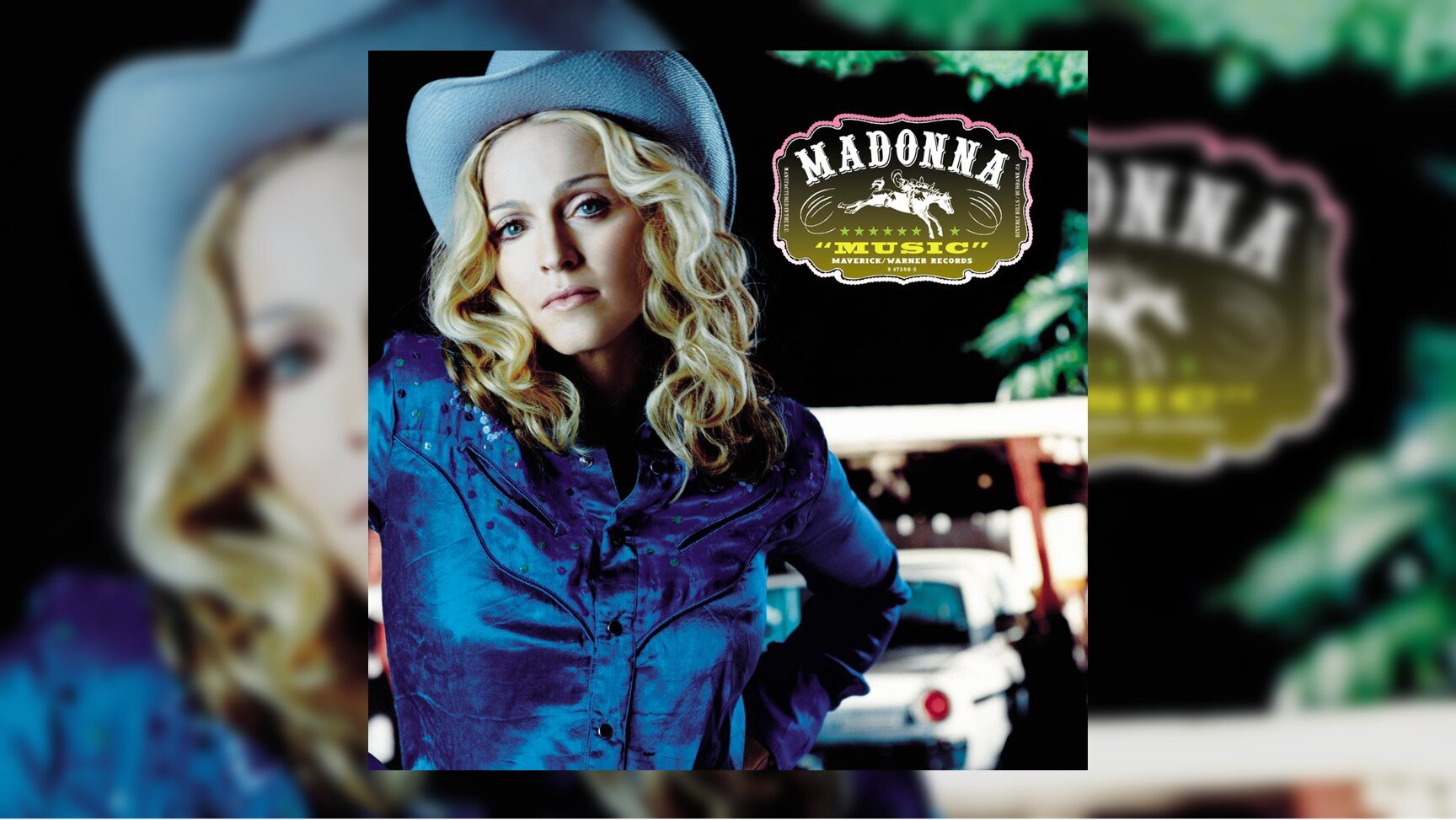

Happy 20th Anniversary to Madonna’s eighth studio album Music, originally released September 18, 2000.

Written and performed by Don McLean, “American Pie” doubled as the introductory single and title to his sophomore album of the same name—both were issued in late 1971. The song was a true slice of folk-rock Americana centered somewhat on the loss of innocence; McLean drew a symbolic parallel to a significant event in American pop culture to flesh out that concept: the deaths of rock idols Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens and Perry “The Big Bopper” Richardson Jr. in 1959. “American Pie” went on to become a requisite chart smash of its day—edited down from its nearly nine-minute expanse for radio—and achieved critical acclaim. Given all the history associated with McLean’s inaugural take, it was a song not many dared to approach.

The Next Best Thing, the final entry in the venerated oeuvre of film director John Schlesinger, was also Madonna’s penultimate acting venture. Alongside her leading man Rupert Everett, the singer-actress stirred up some charming chemistry. Ultimately though, mixed reviews tanked the flick upon its disclosure on March 3, 2000—however, its soundtrack did curry favor. Among entries from Manu Chao, Christina Aguilera, Moby and Groove Armada (to name some) were two freshly minted tracks from Madonna: “Time Stood Still”—an original—and an ambitious cover of the McLean staple “American Pie.” The latter cut was used as a minor plot device in The Next Best Thing and as the lead-off single for its companion album.

Like “Beautiful Stranger” in 1999, “American Pie” wasn’t commercially put forward as a physical single in the United States—it was confined to an airplay-only release domestically. Overseas, “American Pie” got the proper rollout. Madonna’s sensitive, electro-pop revision—with co-production assistance courtesy of colleague William Orbit—connected with audiences. Specifically, in the United Kingdom, “American Pie” awarded Madonna with her ninth number-one single.

It wasn’t every day that someone could take another individual’s definitive artistic statement, make it their own and turn it into an unequivocal commercial victory 29 years later. Then again, Madonna isn’t just anyone. The “rustic chic” direction of the “American Pie” music video—courtesy of Philipp Stölzl—forecasted what was coming visually for her eighth studio set Music, but sonically, the single was just a mere warm-up for the Queen of Pop.

Due in the second half of 2000, Music promised to be a big payoff in all quarters.

The scripting for Music started in September 1999 and stretched into the incipient half of 2000. Guiding the sessions for the project was Madonna’s desire to maintain the album-oriented cohesion emblematic of Bedtime Stories (1994) and Ray of Light (1998). As she had on those two anterior efforts, a partial “changing of the guard” was enacted, but William Orbit—Madonna’s chief partner on Ray of Light—remained. Together, they drafted “Runaway Lover” and “Amazing,” two selections that revisited the vibrant psychedelics and polite digital accents of “Beautiful Stranger” and “American Pie.”

The expected infusion of new blood was demarcated by additional collaborations with writer-producers Guy Sigsworth, Damian LeGassick, Mark Stent, Talvin Singh and Joe Henry—Madonna’s brother-in-law—all of whom aided in further rounding out the record. However, stationed to primary production and co-writing duties in tandem with Madonna for six sides on Music was Mirwais Ahmadzaï. Their paths crossed at the onset of the album’s birth, à la Madonna’s manager Guy Oseary, when the French song constructionist submitted a demo tape to her Maverick Records imprint for consideration. While Ahmadzaï didn’t end up onboarding at Maverick, his avant-gardist approach sparked an instant connection between both parties.

Opposite to the warming techniques employed for the electronica found on Ray of Light, Music fostered Madonna’s interest in juxtaposing organic and inorganic sounds. Whether it is the serrated, electro-hop edge of the title piece, the amber-hued acoustica of “I Deserve It,” or the string-laden “Paradise (Not For Me)”, Music is an eclectic study of electro-funk, folktronica and chamber pop finery—amongst other sonic textures.

Focusing on the guitar work on “I Deserve It,” the instrument became a lively foil to the twitchy production gadgetry that buzzed on that entry as well as “Nobody’s Perfect” and “Don’t Tell Me.” Although not necessarily in the league of Orbit, Sigsworth or any of the other seasoned guitarists at work on Music, Madonna taught herself to play the acoustic variation of the instrument—this was yet another layer of compositional complexity added to the LP.

Madonna further pursued exploring the aesthetic space between the natural and the artificial as a singer on Music. The limited, artful use of the vocoder—notably on “Impressive Instant” and “Nobody’s Perfect”—is beautifully contrasted against Madonna’s unadorned vocals on “What It Feels Like for a Girl” and “Gone.” The former selection is a stirring examination of girlhood anxieties—crowned with a striking Charlotte Gainsbourg quote from the 1993 film The Cement Garden—that signposts one of two topical arcs that inform the collection: introspection and levity.

Guy Ritchie—the laddish British auteur that romanced (and eventually wed) Madonna during her eighth record’s gestation—was an endless source of inspiration for her. It is likely that the complexities of her relationship with Ritchie were transposed onto “Don’t Tell Me,” an ode to adult love that began life as a product of Joe Henry’s musical imagination as “Stop.” Madonna and Ahmadzaï reworked “Stop” into “Don’t Tell Me” to suit her requirements, thematic or otherwise.

Elsewhere, the spiritual existentialism of Ray of Light sweeps back in on “Paradise (Not for Me)” and “Cyber-Raga.” “Cyber-Raga”—which backed “Music” on its B-side and was assigned to the international iterations of Music along with “American Pie”—saw Madonna return to the mesmeric Sanskrit musings of “Shanti/Ashtangi,” a deep cut from her seventh LP.

The lighter fare on Music proved to be just as gripping as the serious song stock. Not too dissimilar in its narrative structure from “Into the Groove” or “Vogue” is “Music”—a clarion call for unification and expression through dance music culture. However, “Impressive Instant,” “Runaway Love” and “Amazing” use amative attraction—albeit fictional—in its various states as lyrical fuel. Madonna imbues all four selections with a seemingly dichotomous blend of instinctiveness and emotional maturity.

In describing the mystique of the creative process that governed Music in a September 2000 Rolling Stone cover-story interview, Madonna explained, “Creativity is sometimes unconscious, subconscious, conscious—and often it’s a mixture of all three. And to try to explain it sometimes—it’s like talking about love, you know? As soon as you start talking about it, you’ve formed a new opinion about it, and it’s obsolete.”

Released four weeks prior to the album’s arrival, lead single “Music” performed to critical and commercial expectation in every market and its partnering video clip was equally popular. Cleverly disguising her pregnancy—she and Ritchie’s son Rocco was born on August 11th—Madonna took a satirical swipe at the excess of hip-hop culture; her longtime friends Debi Mazar and Niki Harris also star. British comedian Sacha Baron Cohen (in his “Ali G” persona) acts as the limousine driver escorting Madonna and her gal pals throughout the video’s runtime.

The blockbusting success of Music extended into 2001 with the release of “Don’t Tell Me” and “What It Feels Like for a Girl” as singles; “Impressive Instant” was set-up as a possible fourth single—promotional copies were pressed and remixes commissioned—but it went no farther. “Don’t Tell Me” and “What It Feels Like for a Girl” each made respectable chart headway, however Madonna briefly (and unnecessarily) courted controversy with the video treatment for “What It Feels Like for a Girl.” Supervised by her husband, Madonna exacts violent retribution against the entrenched patriarchal system. Lost underneath the brash, celluloid spectacle—and the ensuing furor it kicked up—was the actual message for “What It Feels Like for a Girl.” A generic electro-pop single edit, remitted by the remix disc jockey duo Above & Beyond, only muddied things more.

That misstep was soon forgotten once Madonna took her show on the road with the “Drowned World Tour” in June of 2001; her fifth concert series was a triumphant reclamation of the stage after a gap of eight years. Madonna capped off her busiest twenty-four-month cycle—up to that point—with GHV2 (2001), her second formal singles compilation.

Two decades parted from its launch, Music is one of four records in a stratum to denote an imperial period for Madonna (creatively) which spanned from 1994 to 2003. I remarked about the staying power of this effort in my book Record Redux: Madonna, “Music proclaimed that Madonna could party, contemplate and sustain her visionary proclivities all on one album.” Music is a singular example that anything was possible for Madonna when she fixed her sights solely upon her craft—only the sky was the limit of her reach in those days.

Editor’s Note: Read more about Harrison’s perspective on Madonna in his book, ‘Record Redux: Madonna,’ available physically and digitally now. Other entries currently available in his ‘Record Redux Series’ include Carly Simon, Donna Summer and Kylie Minogue. An overhauled version of his first book ‘Record Redux: Spice Girls’ will be available in early January 2021.

Note: As an Amazon affiliate partner, Albumism may earn commissions from purchases of vinyl records, CDs and digital music featured on our site.

LISTEN: