Happy 40th Anniversary to Madonna’s eponymous debut album Madonna, originally released July 27, 1983.

It’s easy to picture her dancing in front of Mark Kamins’ DJ booth that night in 1982 at the four-story New York nightclub Danceteria, because a couple years later Desperately Seeking Susan would nearly replicate the scene. Madonna Louise Ciccone, still new to New York from Rochester, Michigan, showing off some of her sensual moves before swaggering through the crowd of sweating bodies with a cassette in hand, ready to unleash some of her signature chutzpah.

Everyone knew that Mark Kamins, in addition to his regular gig at Danceteria, was a party DJ for Talking Heads, and an A&R guy for Island Records. So Madonna sidled up to him, and handed him the demo for her song “Everybody.” “I was flirting with him,” she admits. Madonna was a regular at Danceteria, and even in a “creative cauldron” of a club where Sade was a bartender, LL Cool J was the elevator operator, and the Beastie Boys and Keith Haring were busboys, Madonna stood out.

“She had this spark, a certain energy, that transcended everybody else,” Kamins remembered. And so he put the song on right then and there, without listening to it first. “I love spontaneity, I believe it’s the magic of life. Madonna had a cassette, I threw it on, and it worked,” he said, shrugging at the memory. “I’m not sayin’ the place went mad crazy, but it worked.”

At that point, even as an unknown in 1982, Madonna was already a well-established risk taker. “Growing up in a suburb in the Midwest was all I needed to understand that the world was divided into two categories: people who followed the status quo and played it safe, and people who threw convention out the window and danced to the beat of a different drum,” she wrote in a 2013 essay for Harper’s Bazaar. “I hurled myself into the second category.”

Instead of focusing on fitting in, she focused on her future. “For me, that was going to New York to become a REAL artist,” she recalls. “To be able to express myself in a city of nonconformists. To revel and shimmy and shake in a world and be surrounded by daring people.”

According to lore, Madonna arrived in New York in 1978 with $35 to her name, and told the cabbie, “Take me to the center of everything,” and so he dropped her off in Times Square. It was there that she got a job at Dunkin’ Donuts, until she got fired for (allegedly) squirting jelly in a customer’s face. The daughter of a devoutly Catholic Italian-American father and French-Canadian mother, Madonna lost her mother, Madonna Sr., to breast cancer when she was five years old. The oldest girl in a family of eight kids, Madonna grew up fast after her mother’s death, taking care of her younger siblings and rebelling against mainstream conventions (although for a while in high school she was a popular cheerleader). She began gravitating towards an edgy style and stopped shaving her legs and armpits.

She soon gave up cheerleading for ballet classes at a little studio on Main Street in Rochester. It was at this studio that she met Christopher Flynn, her dance teacher, mentor, and an out-and-proud gay man who would have an enormous influence on her life. Sensing a natural talent in her, he demanded a laser-focused discipline to her craft, but he also took her to art galleries and concerts in Detroit, as well as out dancing at some of the city’s hippest gay clubs.

It gave young Madonna, who was accustomed to taking charge at home (and, eventually, everywhere else), an entirely new self-concept. “I kept seeing myself through macho heterosexual eyes. Because I was a really aggressive woman, guys thought of me as a really strange girl. They didn’t want to ask me out. I felt inadequate,” she recalls. “And suddenly when I went to the gay club, I didn’t feel that way anymore. I just felt at home. I had a whole new sense of myself.”

Watch the Official Videos:

She was also exposed to a more racially diverse crowd in Detroit than she was in mostly-white suburban Rochester and that, too, became her new normal. Another byproduct of these years was that Madonna, for the first time, began to feel beautiful. In a 1991 interview with Carrie Fisher, she told the actress that she had never felt attractive as a child. “So when did you?” Fisher asked. “When I started hearing it from my ballet teacher when I was about sixteen,” Madonna answered. “By then you had solidified the impression that you were not attractive?” Fisher inquired. “I thought I was a dog from hell,” said Madonna.

Madonna graduated from high school a semester early and, endorsed by Flynn who was about to take up a professorship there, she was awarded a dance scholarship at the University of Michigan. In 1977, after a year at the university, she won another scholarship to the prestigious Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater for its summer workshop in New York. When she returned to Michigan, she began working with choreographer Pearl Lang, a visiting artist-in-residence at the university. Lang recognized Madonna’s talent, and encouraged her to ditch her university program for the world of professional dance in New York. Christopher Flynn co-signed the move, and Madonna didn’t need to be encouraged any further.

After securing the ill-fated Dunkin’ Donuts job after her inaugural New York taxi ride in 1978, Madonna joined the American Dance Theater, where Lang and Ailey each ran their own companies, as an understudy. At night, she got into the local punk scene—she worshipped Debbie Harry and Chrissie Hynde—and started dressing in ripped pantyhose, safety pins, lingerie as outerwear, and big rags as hairbows. Pearl Lang eventually got her a better job as a coat-check girl at the Russian Tea Room. “Because I thought she was losing weight and needed one decent meal a day,” Lang recalled.

Not long after joining Lang’s company, Madonna was walking through a rough part of town when she was grabbed by a man at knifepoint and dragged up the stairs of a building, onto the roof. He raped her, leaving her crying and shaking uncontrollably. She sat there for a long time, afraid to leave in case he was waiting on the stairs. It was one harrowing experience in a series of many. “New York wasn't everything I thought it would be,” Madonna wrote in 2013. “It did not welcome me with open arms. The first year, I was held up at gunpoint. Raped on the roof of a building I was dragged up to with a knife in my back, and had my apartment broken into three times. I don't know why; I had nothing of value after they took my radio the first time.”

After the rape, she quit the dance company. Her self-esteem had temporarily been shattered, and she had also begun to realize that it would take years of strenuous work to become a principal dancer, much less a choreographer. She turned to the club scene to forget her troubles. In 1979 while out dancing, she met a musician named Dan Gilroy who had a band with his brother Ed called The Breakfast Club. Madonna and Dan began dating, but their relationship took a pause when Madonna got a job in Paris with a disco revue. It picked back up when she returned to New York in 1980, with Madonna joining the Breakfast Club as a drummer and occasional singer.

Eventually, Madonna and Gilroy broke up and she started a short-lived rock band called Madonna & The Sky. Then, Steve Bray, an old boyfriend from Michigan, moved to New York, and he and Madonna began writing songs together. They called their group, simply, Madonna (even though Bray thought it sounded too Catholic, and narcissistic). For a while, the duo were picked up by a small management company, which allowed Madonna to move to a safer neighborhood.

At that point, Madonna and Bray were still making rock music, but her heart wasn’t totally in it. Against the advice of their management company, they began to write funk-infused songs, and a result of those writing sessions was the single “Everybody.” Madonna approached DJ Mark Kamins with the demo that fateful night at Danceteria, and everything changed.

Madonna and Kamins started dating, moving into a railroad apartment on the Upper East Side. Kamins arranged a meeting with Chris Blackwell at Island Records, but Blackwell wasn’t impressed by Madonna’s demos. “He didn’t want to sign his A&R’s girlfriend, and she’d had a rough night, she hadn’t taken a shower, so Chris said she didn’t smell too good that day,” Kamins remembered. After Blackwell’s rejection, Kamins took Madonna to meet Seymour Stein at Sire. “Seymour was in the hospital at the time,” Madonna told Rolling Stone. “I got signed while he was lying in bed in his boxer shorts.” Stein remembered the day similarly. “When Madonna came by, I was caught with dirty pajamas with a slit up the back of my gown,” he said. “I saw a young woman who was so determined to be a star.”

A session for “Everybody” and a song called “No Big Deal” was booked at Blank Tape Studios in the summer of 1982. Steve Bray was relegated to the sidelines, and Kamins assumed the role of producer. “Everybody” is full of bubbly, youthful energy, but it was stripped-down and had edge, too, and so Fab Five Freddy would allegedly soon hear it blasting from a boombox carried by Puerto Rican teenagers. Like many a Madonna song, it’s an invitation—and a demand—to dance, an ode to the transformative power of the nightclub. In January 1983, the record peaked at #3 on the dance charts. Madonna then wrote “Lucky Star” about Mark Kamins.

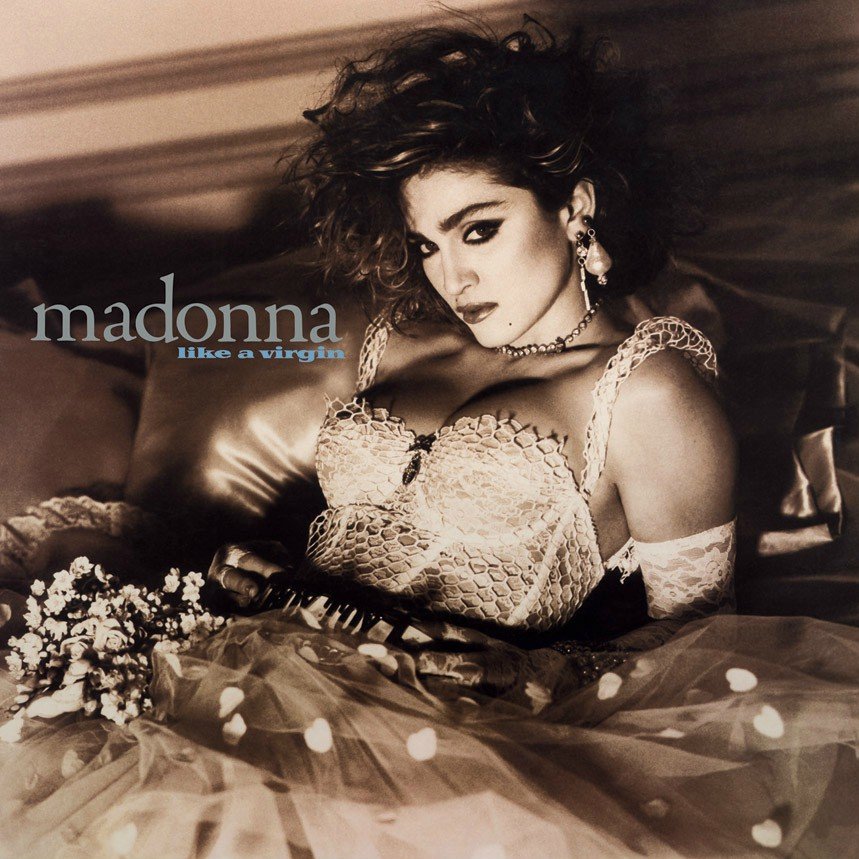

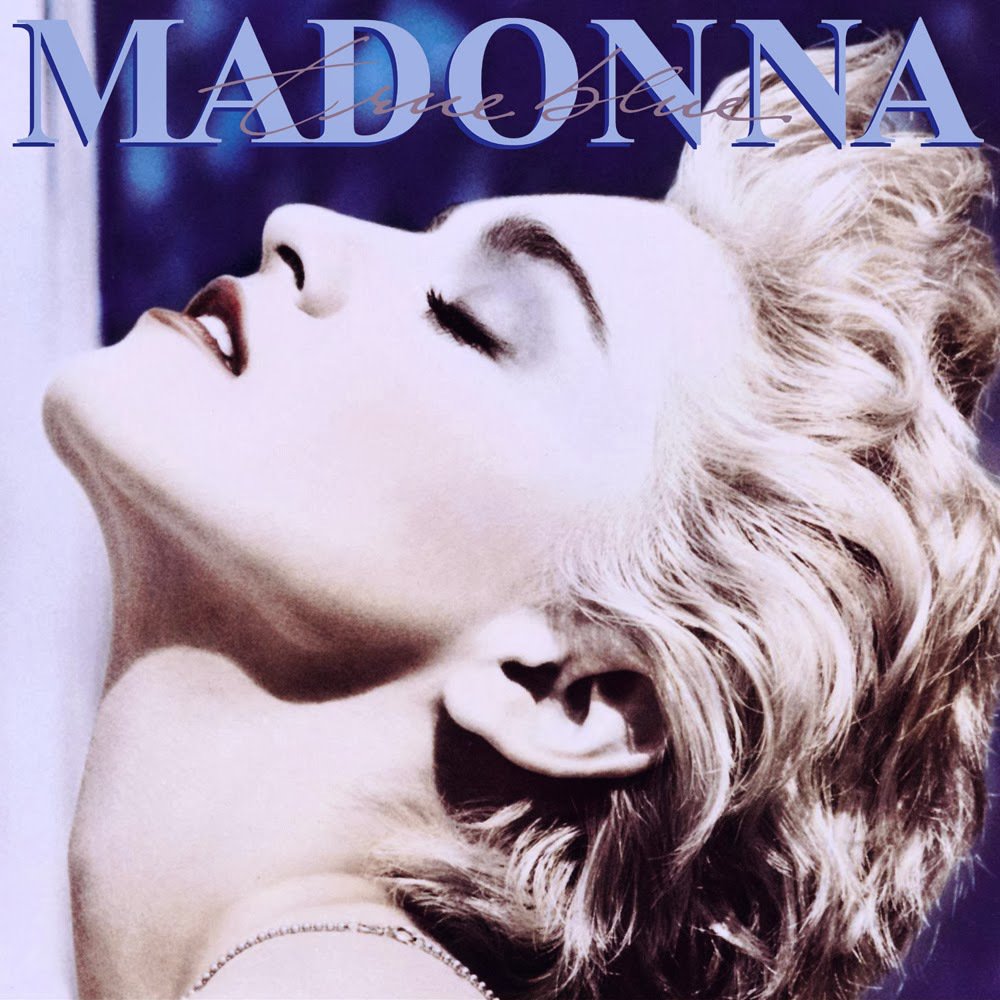

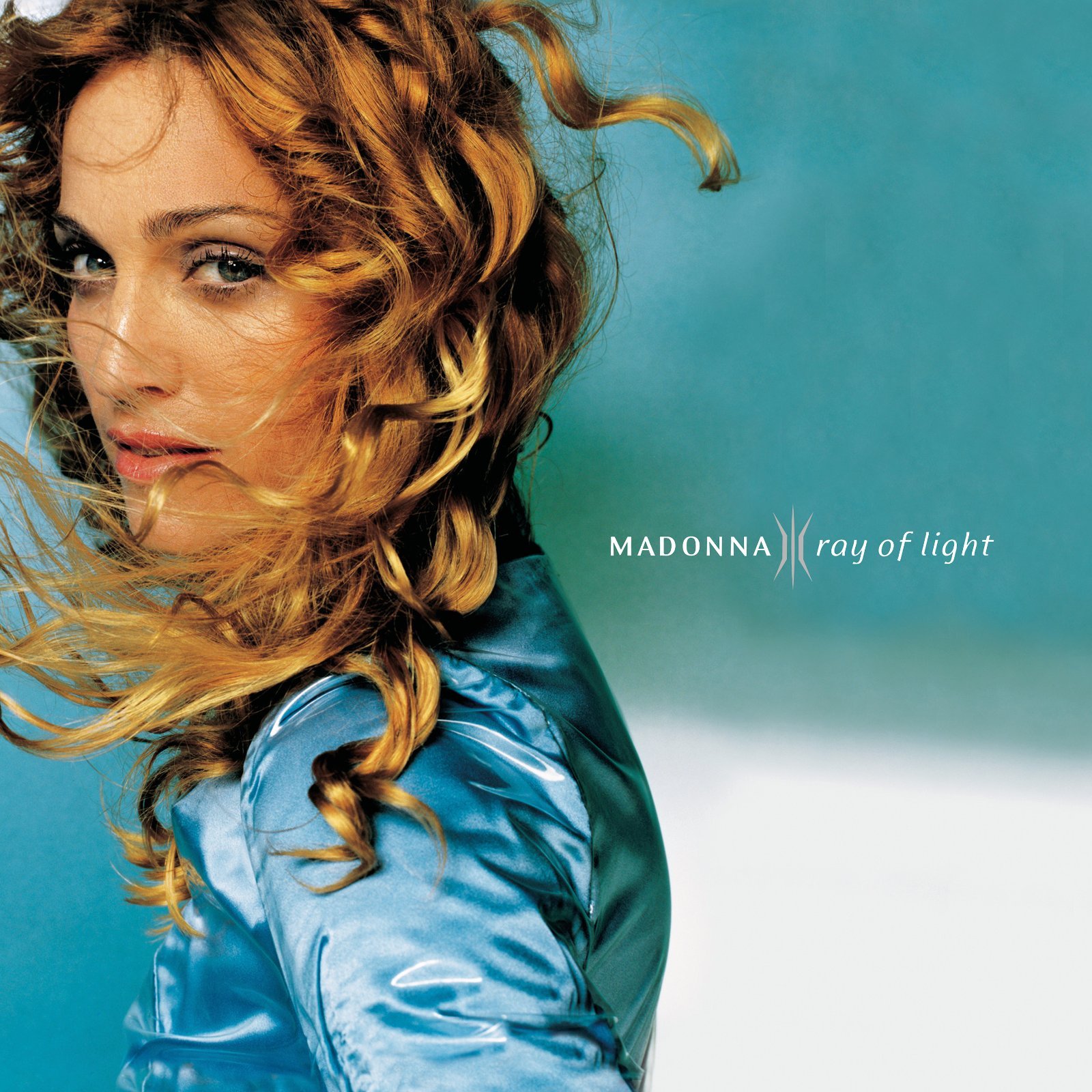

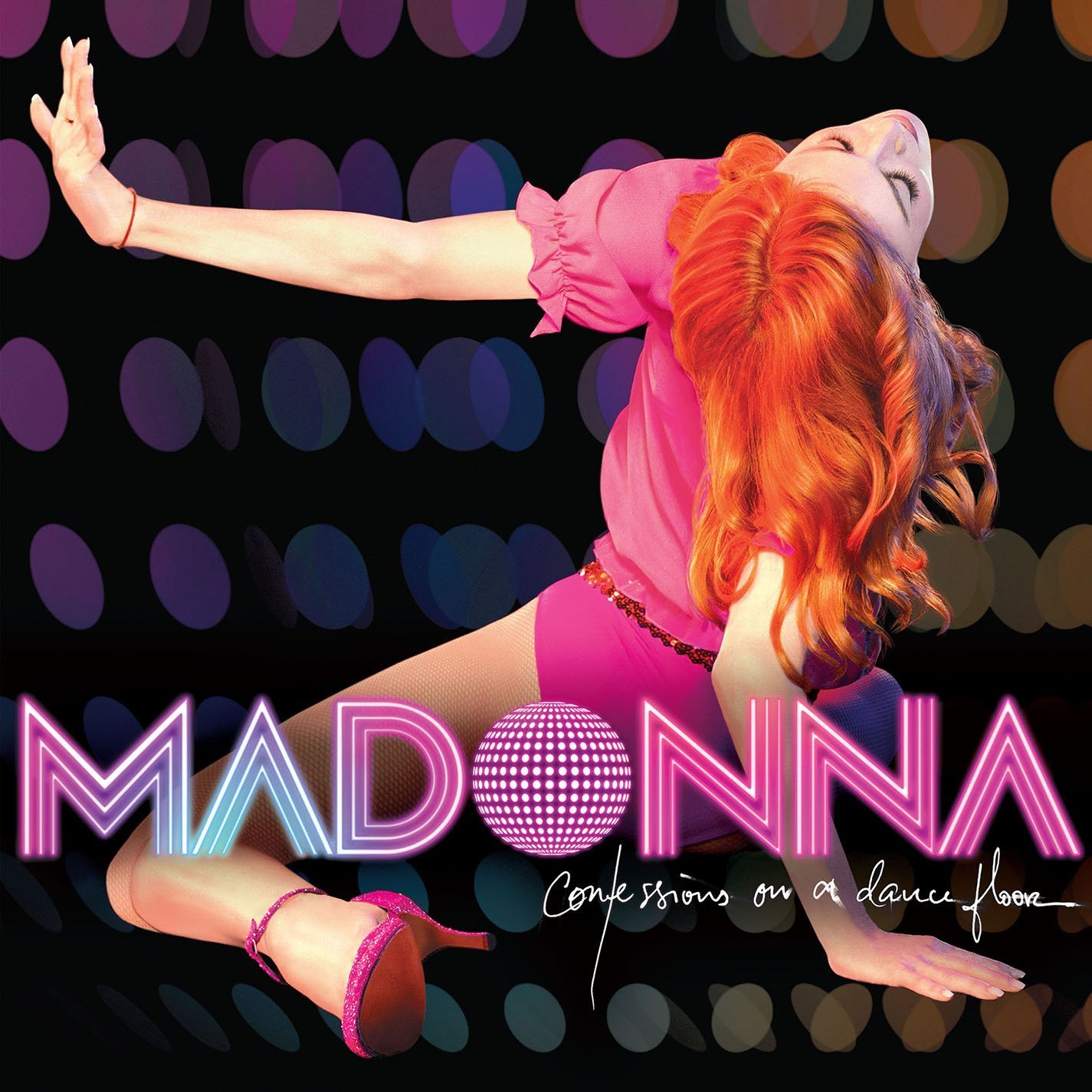

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about Madonna:

As “Everybody” started becoming a hit, Madonna had a brief romantic dalliance with artist Jean-Michel Basquiat, but it soon died out due to a stark difference in lifestyle. According to Basquiat’s assistant Steve Torton: “I saw her at Bond’s and I said, ‘How’s Jean?’ and she said, ‘He’s on dope. I went over there tonight and he was nodding out on heroin. I’m not having anything to do with that.’”

While Madonna and Basquiat were breaking up, she began writing her second single “Burning Up.” Mark Kamins assumed that he’d be producing it, but Madonna’s record company chose R&B mover-and-shaker Reggie Lucas. Kamins wasn’t all that upset, understanding that Madonna needed someone who could achieve a more robust vocal sound (“Everybody,” Kamins admitted, sounded a bit thin). Plus, Kamins had been shrewd enough to sign Madonna to his own production company, ensuring that he’d receive a percentage of future royalties.

“Burning Up” is about blazing lust, and unrequited love. It has a quintessentially ’80s synth vibe, but the first time I heard it since my ’80s childhood—in fact, I had completely forgotten about it —was in the early 2000s, when I had just made my own move to New York. My friend Dahlia was in an electroclash band, and they would often perform “Burning Up” as part of their set. Maybe because of how seamlessly it fit into that early-aughts music movement—it’s stark, and unconventionally punky—I tend to regard “Burning Up” as both forward-looking and timeless.

“Burning Up” became Madonna’s first video for MTV. She shimmies sexily in the middle of a highway, waiting to be run down by her reckless boyfriend in a convertible—until the very end of the video, where she subverts convention and ends up being the one driving the car. MTV was a medium Madonna would grow to dominate, and it allowed her to craft a much more complex artist statement than she ever would have been able to simply through her music.

Over the decades, she would continue to subvert—kissing a Black saint, introducing mainstream America to gay club culture, flirting with BDSM, and weaving an intricate world of diversity—via her videos. Madonna is, at heart, a multimedia artist, and it was her earliest videos, including “Burning Up,” that first attracted the attention of social critic Camille Paglia, whose scholarly essays in the early ’90s would solidify Madonna as a post-modern icon and socio-political force to be taken very seriously.

“Madonna, role model to millions of girls worldwide, has cured the ills of feminism by reasserting woman’s command of the sexual realm,” Paglia would assert. Sex-positive Third Wave feminism followed (with the Riot Grrrls riding Madonna’s coattails), as did an entire niche of academia dubbed Madonna Studies. In fact, the subject of Madonna was my first formal introduction to feminism when my English Comp class was assigned Paglia’s essays my senior year of high school. And it resonated—big time. I was only 7 or 8 years old when Madonna first became truly famous in the mid-’80s, but I knew—as did every little girl—that this woman was radically transforming what it meant to be born female.

To capitalize on her MTV success, Madonna went on a promotional club tour with dancers Erica Bell, Bags Riley, and Martin Burgoyne. (The latter’s eventual death from AIDS would devastate Madonna and spark her activism for a cure). “You couldn’t take your eyes off her,” said Ginger Canzeroni, former manager of The Go-Go’s, who saw Madonna on that tour. “She was very attractive, she was street. There was something different about her.” When Madonna returned, Sire decided that she was ready to make an album and sent her into the studio with Reggie Lucas.

At times, Madonna and Lucas clashed because she favored a minimalist approach, whereas Lucas preferred complexity. Eventually, she’d recruit another club deejay, John “Jellybean” Benitez, to remix some of Madonna’s tracks before the album was released. The end result was a funky New Wave disco album that became a snapshot of both downtown New York, and pre-fame Madonna herself.

The post-disco “Borderline,” to Madonna, was too nuanced and subtle, possibly because it doesn’t have a clearly delineated chorus (though it would become a hit). “Lucky Star,” on the other hand, with its shimmer, bounce, and earworm chorus, is a prime example of Madonna’s winning simplicity. As a dancer, she knew instinctively what would make someone bop their head, or get out on the floor.

“I Know It” is a slightly hokey, baroque-leaning number about the dissolution of a romance that’s very ’80s throwback—in the most dated way. “Holiday,” a last-minute add-on produced by Jellybean Benitez, is one of my all-time favorite Madonna songs, one that manages to capture both exuberance and introspection. As a child of the ’80s, I’ll always link “Holiday” with Cyndi Lauper’s hit of the same year “Girls Just Wanna Have Fun”—and each are more powerful for their association with the other. Both songs convey an ebullient celebration of being a defiant, wholly modern girl.

“Think of Me” fuses ’70s disco with some very ’80s saxophone. It’s kitschy in a fun way, one of those obscure, forgotten Madonna tracks that you could throw on at a party and people would still tear up the dance floor, recognizing immediately who it is. “Physical Attraction” is another kitsch-fest, though not as catchy, with steamy lyrics about lust, soulful ooh-ahh backup vocals, and glittery synth. It conjures a purple laser backdrop and a very powerful smoke machine.

The album ends as it all began with “Everybody,” a swaggering, zigzagging anthem where Madonna uses some of her well-honed sex appeal to breathily invite you, you, and yes, YOU, to the dancefloor. “Everybody, come on dance and sing/ Everybody get up and do your thing,” she sings over and over until it becomes a hypnotic mantra working its way under your skin. Just as we can easily picture her moving through the Danceteria with attitude, Mark Kamins could still picture her, too: “When she danced, everyone would stand around her.”

Listen: