Happy 25th Anniversary to Elliott Smith’s third studio album Either/Or, originally released February 25, 1997.

I first became aware of Elliott Smith from a mixed tape, which is—or was—probably one of the more intimate ways you can learn of a song, or an artist. It was the mid-to-late ‘90s, I was in college in Pennsylvania, and the tape came in the mail with a handwritten letter from my friend Kara. The tape, too, was handwritten—the pre-printed grid, delineating sides A and B, crammed with Kara’s messy handwriting. There were no doubt many good songs on that compilation, but the song that really stuck out was Elliott Smith’s “Angeles” from his album Either/Or.

Someone’s always coming around here

Trailing some new kill

The English major in me appreciated the poetic shock of that first line, how it evoked sheer, vicious survival in contrast with Smith’s quiet, understated vocals and intricate fingerpicking. I liked how the song was about a city, but, through Smith’s direct address, could also be construed as being about a love interest, with “Angeles” sounding almost like “Angela” if you weren’t listening with perked ears.

Its sound reminded me of my mom’s ’60s folk records, which I’d sit and listen to for hours on Saturdays growing up, my mother’s maiden name written in loopy teenage scrawl on each record jacket, giving me a glimpse into the girl she once was. But the punk edge to the lyrics, and a willful nonchalance to Smith’s voice, made it not your mother’s folk.

I’m not sure how Kara came across Elliott Smith. We were both into our local punk-rock scenes to one degree or another—me in PA, she in Virginia, but Kara was also a cinephile, and so it’s more likely she would have come across his music in the 1997 blockbuster Good Will Hunting. Director Gus Van Sant had somehow stumbled across Smith’s music and knew immediately that it could fit with the film’s mood. “I think even before we started shooting I was thinking in terms of Elliott’s music,” Van Sant told Boston Magazine. “But I didn’t know until finally we were able to put it in whether it was going to work.”

Van Sant decided to use it first, ask permission later. “We contacted him and sort of gingerly explained to him that we put his music all the way through our movie, and would he consider letting us [use] it,” Van Sant said. “And so he watched the movie in my house and said yes. And then he did the last song ‘Miss Misery’ at the end. We wanted an original song. The ones that we were using had already been released.”

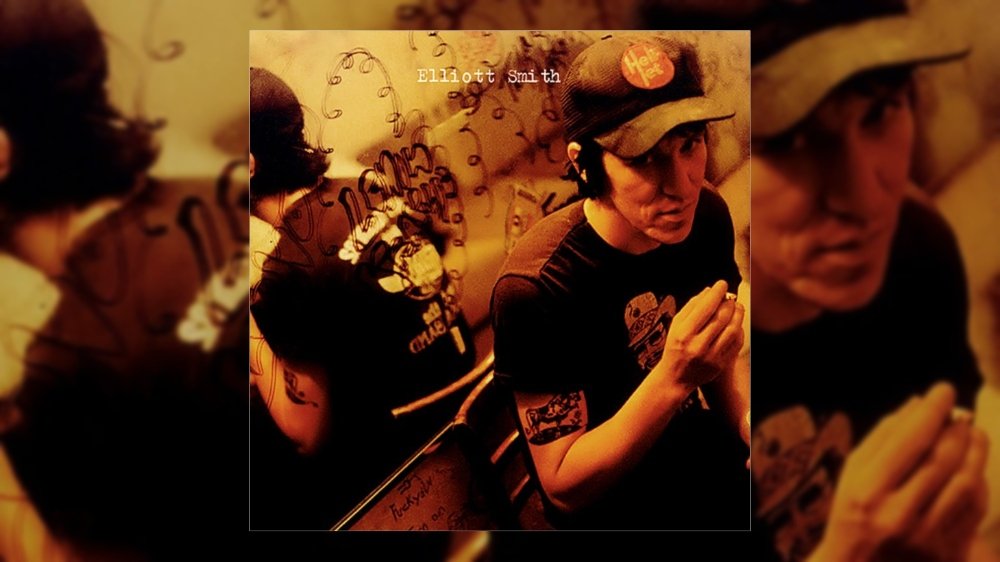

Three of the songs used, including “Angeles,” are from Smith’s 1997 album Either/Or, regarded as Smith’s last album before he got his “big break” and was signed to a major label (DreamWorks). On the cover, he looks like every late ’90s punk-rock dude, with his shrunken T-shirt, tattoos, and thrift-store trucker hat that Von Dutch would later make their own and charge a fortune for.

I loved Good Will Hunting, just like everyone else in 1997—and beyond. Stellan Skarsgard, who plays the MIT professor who takes Matt Damon’s Will under his wing, still marvels at the impact the movie has had. “It’s amazing how often people come up to you in airports and on streets and start talking about it and say, ‘I see it at least once a year,’ or ‘I’ve seen it 30 times.’ It’s a film that people carry around with them in a way.” The story of how Matt Damon and Ben Affleck, two Boston unknowns, wrote the screenplay and launched bright careers through it was admirable. I also loved Robin Williams, an absolute gem of an actor, as the grieving therapist who’s able to reach, inspire, and transform the kid from the wrong side of the tracks.

The stark contrast in Good Will Hunting between run-down Southie and fancy Harvard and sleek MIT could be seen out my own window at college each day. I was living in Bethlehem, a depressed eastern Pennsylvania steel town with the abandoned, rusted carcass of Bethlehem Steel in the center of the dilapidated south side, contrasting starkly with the stone majesty of Lehigh University’s idyllic campus.

It wasn’t really my vibe—the campus revolved around a hard-partying Greek system—but I had found enough weirdos through the English department and the Art department to forge a happy existence. I had other worries, though. My mom had been diagnosed with uterine cancer my sophomore year, and so I was spending lots of time shuttling back and forth between college and Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C., where she was receiving treatment.

I was scared, and I was sad, and, because my parents were divorced, I was also doing it alone. But Smith’s Either/Or provided just the right sound and comfort during that time. Something I could listen to softly in my bedroom, or on my headphones, and know that someone understood that quiet fight for survival, even if my fight was on my mom’s behalf.

Either/Or definitely presents as an album, rather than a collection of songs, in the sense that it has a well-honed, overarching sound, with each song presenting as a variation of mood or theme. “Speed Trials” is rhythmic, mellow and folky with a matter-of-fact sadness, meaning it doesn’t try to jerk tears out of you, but sits with you while you dab at your eyes. In contrast, the second track “Alameda” evokes a lo-fi Polaroid mood, with soft “Ooohhh” harmonies and lyrics like “You walk down Alameda looking at the cracks in the sidewalk / Thinking about your friends.” We’re anchored to a sense of place in this song, and that place is low-key and sunny. “Nobody broke your heart,” Smith assures us over and over in the chorus.

“Ballad Of Big Nothing” has a very distinct Beatles sound, and an infectious melody. It’s on this song that Smith’s voice is the surest and strongest, and it’s apparent that he’s having fun with it. “You can do what you want to / Whenever you want to,” he sings. But then the mood flips again on the next song, “Between The Bars,” where Smith’s voice is back to a near-whisper, and the pace is slow-moving and melancholy. “Pictures Of Me” builds suspense in the beginning with percussive guitar, which then turns into a rocking melody that’s less folky and nearly glam rock, and the message is that Smith isn’t what he appears to be, or how people perceive him. “So sick and tired of all these pictures of me / Completely wrong / totally wrong.”

“Rose Parade” is my second favorite song after “Angeles.” It has a nice, easy rhythm that reflects the meandering pace of a Saturday parade, and once again provides that anchored sense of place, again Los Angeles. The album ends with “Say Yes,” which is the song Gus Van Sant chose to use during the early development of Will and Skylar’s relationship in Good Will Hunting, before Will (temporarily) fucks it up with his fear of intimacy. So, the album ends on a hopeful note.

Smith ended up being nominated for an Oscar for “Miss Misery,” the original song he wrote specifically for Good Will Hunting. It plays as Will drives towards California and Skylar and the credits roll. Smith wore a white suit and performed it alone on the big stage, projecting an air of rare (for the Oscars) authenticity, and vulnerability. The song didn’t win—Céline Dion’s “My Heart Will Go On” from Titanic was chosen. “His [Smith’s] performance at the 70th Academy Awards, sparse and sad and so unlike the overly produced awards shows to come, feels like a cultural artifact that can never be recreated,” wrote critic Roxana Hadidi.

After several months of treatment, my mom’s cancer went into remission, and she has, thankfully, stayed cancer-free ever since. That album, and well-curated mixed tapes from friends, helped get me through a difficult time. Elliott Smith, however, didn’t fare as well. The addiction and depression that had been trailing him for years finally caught up, and he died by suicide in Los Angeles in 2003. Eleven years later, Robin Williams, who lent so much depth of feeling to Good Will Hunting, took his own life, too.

“Some beautiful songs try to make you think that, for a moment, there’s no crap in the world, that it’s just a beautiful place,” Slim Moon, the founder of Smith’s former record label (Kill Rock Stars), toldSPIN. “But Elliott’s songs admit that the world’s fucked up, and this is just a beautiful moment we get to have.”

LISTEN: