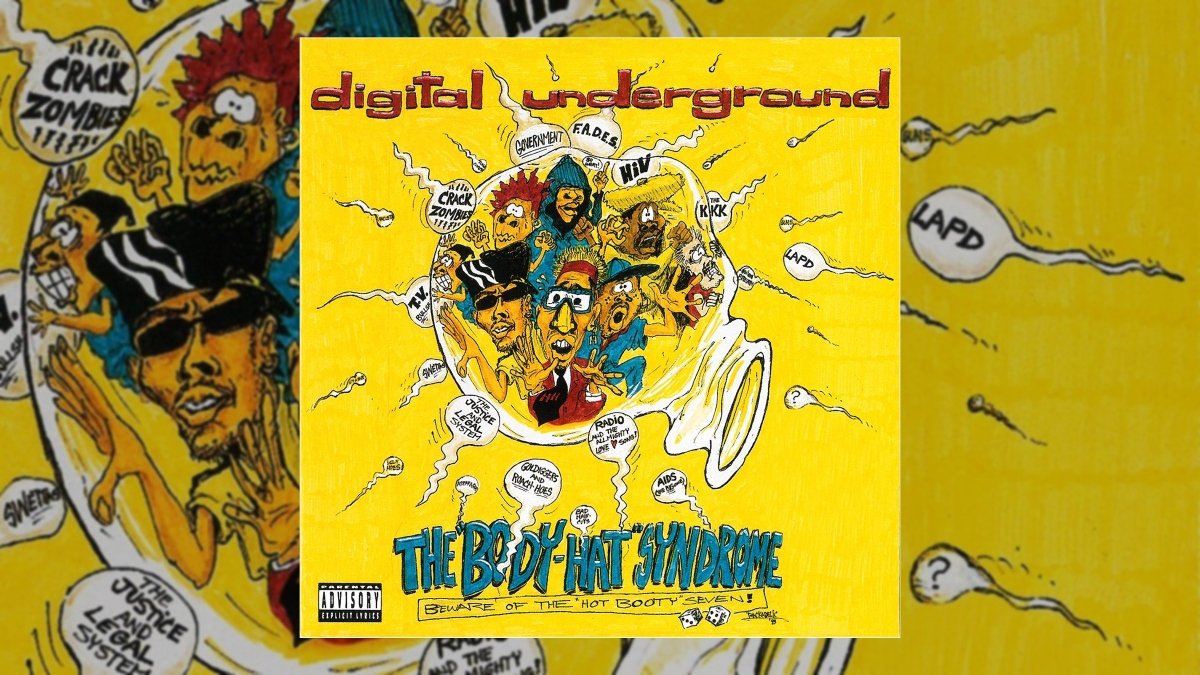

Happy 30th Anniversary to Digital Underground’s third studio album The Body-Hat Syndrome, originally released October 5, 1993.

Digital Underground’s discography is absolutely fascinating. Greg “Shock G” Jacobs, the Bay Area-based group’s architect, was one of hip-hop’s great visionaries. As I’ve written about a few times before, he worshiped at the altar of George Clinton and Parliament-Funkadelic, viewing their music not just as a potential sample source, but as a guiding principle. Shock followed their example and sought to create ambitious projects containing all sorts of big and small ideas, approaching them from angles that most rappers would never conceive.

Digital Underground’s releases might not all be great, but they are never boring. Each has a distinct character and none of them sound like what came before from the group. I’ve written tributes to nearly all of their full-lengths and have found something absorbing about each one.

Which brings us to The Body-Hat Syndrome, the group’s third full-length and fourth project overall. Released 30 years ago, it’s probably the most maligned album in Digital Underground’s catalogue. It was a commercial flop and sustained withering reviews when it was released. And yet, I’ve always enjoyed it. The project is a bit of a greased pig, thus hard to wrangle, but it’s an interesting and frequently entertaining undertaking.

A consistent observation about Tommy Boy Records is that they were a singles label, for better or worse. And to hear it from many of the imprint’s former artists, it was often for worse. If a group or emcee scored a hit record, then the label expected all of your subsequent material to be slightly modified iterations of that same hit.

Which is where Digital Underground found itself after the success of the single “The Humpty Dance.” The certified Gold single was the group’s foot in the door to stardom, fronted by Shock’s alter ego Humpty Hump, setting up the Platinum success of Sex Packets (1990), their debut. After scoring that smash, Tommy Boy now saw Digital Underground ideally as a vehicle for Humpty. When they turned in Sons of the P (1991), their second full-length, the higher-ups at Tommy Boy mandated that they go back to the studio and add more appearances of a character that Shock had first seen as a one-off “joke.” And during the Body-Hat Syndrome sessions, the expectation was that the group would serve as a Humpty Hump delivery system.

“When we were making The Body-Hat Syndrome we felt like we were this group of all these different varieties and MC’s, faces, sounds and abilities,” Shock said in an interview with Vibe. “We felt like we were getting squeezed into just being the Humpty band. Tommy Boy made it seem like Humpty was Digital Underground’s lead rapper … they wanted all our singles to feature him. They were really starting to piss us off. We were fighting for our lives. You have a guy in your group who doubles as three people who are believed to be real. How about promoting that?”

Even further complicating matters was the success of 2Pac’s “I Get Around.” The song, produced by Shock G and featuring guest verses from him and Money B, was at that point the biggest hit of 2Pac’s career. Shock said that Tommy Boy was upset that Shock G didn’t keep the beat so it could be used as a Digital Underground track, preferably featuring Humpty Hump. Shock’s explanation that 2Pac was a member of Digital Underground and the song’s success would only help in promoting the group fell on deaf ears.

Fed up with the interference, Digital Underground delivered their label an awesomely passive aggressive project in the completed Body-Hat Syndrome. “What we were doing is an anti-radio, anti-commercial album on purpose,” Shock explained to Vibe. “We knew we were going to be out of there as a pop group, so we sat down and thought, ‘How can we make a record that our fans would still like, but Tommy Boy would hate?’”

The Body-Hat Syndrome is heavy on ambition and brimming with ideas. The project builds on the central themes of Sons of the P, freeing one’s mind through music, and then takes things a few steps further. It features commentary on the AIDS crisis, corporate and governmental sponsored propaganda, the state of sampling in the early to mid-1990s, and sex and sex work of all stripes. It fires in all of these directions at once, with only the faintest hits of a guiding principle.

Listen to the Album:

Furthermore, their approach to these subjects is substantially more abstract than their other endeavors. Rapping in an odd manner and extensively using non-sequiturs comes with the territory when you’re died-in-wool Parliament-Funkadelic disciples, but The Body Hat Syndrome is even head-scratchingly weird for a Digital Underground album.

Some of that may have to do with the personnel. Shock G brought new voices into the Digital Underground fold, including newcomer Clee, as well as Saafir and the duo No Face. Saafir was a hardened street soldier known for his impenetrable, extremely unorthodox lyrics and delivery, while No Face were a pair of emcees formerly signed to Rush Associated Labels. Their debut, Wake Your Daughter Up! (1990) was an “adult oriented” album that mixed 2 Live Crew-level raunch with Richard Pryor-esque comedy. Saafir would use this album as a launching pad for his masterful debut, Boxcar Sessions (1994), while No Face would go on to release the single “No Brothas Allowed,” the best Digital Underground song not on a Digital Underground album.

Body-Hat Syndrome was also the first album Digital Underground recorded after Shock G lost all of his possessions, including his record collection, to the 1991 Oakland Hills firestorm. In the face of this trauma, Shock didn’t shrink from the challenge. He modified his approach to production, embracing a much less accessible sound. Shock continued to sample Parliament-Funkadelic records, but the beats are much denser and muddier. With this combination of beats and subject matter, it should not surprise anyone that Tommy Boy had no idea what to do with this offering.

It should be noted that Body Hat Syndrome has A LOT of Humpty Hump. Seemingly in response to Tommy Boy’s complaining, the group crams in many, many Humpty appearances throughout the album, featuring him early and often. On the cassette version of the album, two of the album’s first three tracks are Humpty solo exhibitions.

The first is “Return of the Crazy One,” a fittingly unhinged ode to the return of Edward Ellington Humphrey III. Humpty basks in his own glow over both of the song’s verses, celebrating his care-free attitude, and declaring himself “original high yellow rich rigger bum.” The beat plays like the soundtrack for a demented carnival, incorporating organ and a sampled portion of Parliament’s “Aqua Boogie.”

Shock has said that Tommy Boy insisted that “Return…” both begin the album and serve as its initial single. And, truthfully, it would have worked well as an opening salvo to get listeners into the album…had Digital Underground not filmed a potentially X-Rated music video to support it. MTV refused to play a video that incorporated bits of a writhing orgy involving members of the group and possible sex workers. However, it was a big hit on the Playboy Channel.

“Shake & Bake,” the second Humpty solo cut, is an energetic romp, featuring Hump acting a fool over portions of Parliament’s “Funkentelechy.” Again, it’s a song that has many of the trappings of a commercially successful single, except for the fact that Humpty spends much of the track describing explicit sex acts. No song where the emcee labels himself as “the bust a nut double decker, booty-getting heckler / The kinky ho, closet freak, sphincter muscle wrecker” was ever going to receive airplay on mainstream radio, even during the mid-1990s.

The Body-Hat Syndrome’s title track is split into three sections and spread out across the project’s length, breaking the six-minute song into two separate minute-and-a-half portions and another three-minute increment. The subject matter can be a bit tough to decipher, as Digital Underground appears to advertise full-body condoms for everyday life in order to block out the “F.A.D.E.S.,” or “Falsely Acquired Diluted Education Systems.” The emcees in the group continuously pass the mic, with each delivering clusters of lines in short bursts. The track’s beat showcases Shock G’s creativity, as he takes a section of Parliament’s “Flashlight” and severely warps it.

Digital Underground communicates their messages a little more clearly on “Doo Woo You.” It’s a seven-and-a-half-minute dedication to the use of their music as a means for mind expansion and a shield against misinformation, set to a mash of horn-based samples, including pieces of Parliament’s “Rumpofsteelskin.” “Dope-A-Delic (Do-U-B-Leeve-In-D-Flo?)” features Shock G and newcomer Clee working in tandem, encouraging wack emcees to step up their game and follow Digital Underground’s example. “Let this bless you, take you, and make you bigger,” Shock G raps.

The group touches upon serious subject matter with “Wussup Wit the Luv,” the album’s second single. The production strikes the right somber notes as the group explores the ills in the Black community and the obstacles that the population faces in order to live in harmony. The song features a brief eight-bar verse from 2Pac, who vents his frustration. “We try to cry, but still they all die,” he raps. “I try to speak to the youth, and the truth is they all high.”

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about Digital Underground:

The only other time 2Pac appears on Body-Hat Syndrome is as the co-host of the (of course) fictional “Humpty Dance Awards.” The extended sketch is on its surface a goof, as Digital Underground nominates dozens of songs for the best sampled use of the “The Humpty Dance” drum break. However, there was serious thought at work here: Shock G wrote an impassioned screed in the album’s liner notes targeting the rise of sample clearance lawsuits that plagued hip-hop in the post-Cold Chillin’ vs. Gilbert O’Sullivan world. He writes, “[N]o one person can rightfully claim a beat, a melody, or any musical phrase as if they own it … But there are a lot of greedy negotiators and businesspeople who use foul, funked-up legal tricks and tactics off of music that they have no natural right to tax.”

It should not be a surprise that large portions of The Body-Hat Syndrome concern sex, particularly its “darker” side. “Hollywantstoho,” is a dense and chaotic adaptation of Funkadelic’s “Holly Wants To Go To California.” Both Shock G and Saafir describe the nominal Holly’s attempts to get into sex work as a means for financial gain and improved status. “Bran Nu Swetta” features one of the best composed beats on the project, mixing live instrumentation with live sample stabs. Shock G, Money B, and Saafir each take turns discussing women that get too attached too quickly after intimate relations.

“Digital Lover” is another unorthodox recording for the album and a unique entry into Digital Underground’s discography. It’s mostly instrumental, as Shock G chops a relatively small portion of Parliament’s “Aqua Boogie’ (again) and adds in vocal samples from various adult films and Zapp’s “Computer Love.” Aside from brief freestyled verses from Saafir and Clee, vocals are scarce for much of the track’s length. Mostly, members of the crew whisper variations of “You need a digital lover” repeatedly.

The three-part, nearly seven-and-a-half minute “Jerkit Circus” suite is Body-Hat’s sole whiff. The extended dedication to “a place where you can hold your sausage hostage” has some juvenile appeal, just for the creative ways that the crew describe self-pleasure. The sub-text about the fear of STDs is present, as they proclaim “I wanna bust it, but I can’t trust it” and “Sometimes it ain't cool even when you wear a hat.” And Money-B’s verse about embracing masturbation as a result of performance anxiety is something you don’t hear often in sex-related rhymes. But the song’s swirling clutter is borderline unlistenable, not helped by the emcees all shouting their verses.

Sometimes the misfires are more interesting. Even though “Do You Like It Dirty?” is far from my favorite song on Body-Hat Syndrome, I do respect its execution. The song is a “duet” between Shock G and Humpty Hump and plays like a rap version of Funkadelic’s odes to sweaty, freaky, nasty sex. Shock and Hump describe a spur of the moment tryst with a “ho 5-0” who pulls him over, as well as a wild, food-filled foray into carnal pleasure with a separate woman. Shock loops up a portion of Lou Donaldson’s “Pot Belly,” distorting it past the point of recognition.

For all of Body-Hat Syndrome’s excess, it’s fitting that the album ends with “Wheeee!”, where the group embraces the mess. The song was likely recorded in a single take, with the group members starting, stopping, and re-starting their verses. Or freestyling and improvising over the same early 1980s funk grooves. Or just laughing uncontrollably and shouting “WHEEEEEEEE!!!!!!!!” Most of the emcees acknowledge that they’re not on their lyrical A-Game here. Saafir ends his contribution by rhyming, “I smell like, uh, the Bee Gees band… Damn, that shit was wack…”

After The Body-Hat Syndrome’s release and unsurprising commercial flop, Digital Underground got what they wanted: Tommy Boy released them early from their seven-album deal. The group hopped labels a few times, but still released ambitious and occasionally enthralling albums. Though they never could quite shake Humpty Hump, Shock G eventually recorded a solo album that put him at peace with the character.

I have no idea what would have happened if Digital Underground had acquiesced to Tommy Boy’s wishes and spent the rest of their career churning out variations of “The Humpty Dance.” I doubt they would have made it through all seven albums on their contract, as the gimmick would have worn thin. It might have resulted in some fun music, and the group could have coasted for a while on the “I Love the ’90s” tour circuit. Personally, I prefer the direction that they ended up taking. Their music from their post-Tommy Boy days could be difficult and challenging, but it was ultimately more rewarding. And it was unique compared to anything that had been released before or since.

Listen: