Happy 45th Anniversary to Diana Ross’ ninth solo studio album The Boss, originally released May 23, 1979.

In March 1976, the preeminent female super power of Motown Records—Diana Ross—released “Love Hangover,” a smoky slice of disco that was one of three singles to be lifted from her eponymous sixth album issued one month beforehand. The charter became another milestone for Ross and though she seemingly reveled in its luxe compositional persuasion—as overseen by the late producer Hal Davis—Ross was not the staunchest advocate for the genre, at least not yet.

Though disco had transfixed both the club and radio crowds of the mid-to-late 1970s, the sound hadn’t just happened in a vacuum. Uptempo R&B—which sat at the core of disco—had been active in the preceding decade with Motown Records as one of its seminal architects. However, by 1975, that proto-disco chrysalis would fall away to reveal a glamorously fresh sonic form that irrevocably altered the popular music landscape.

Diana Ross, ever an adaptive force of nature all her own, did come around and adjust; she stopped short of completely reinventing herself as some sort of radical dance diva. Instead, Ross began blending her patented soul-pop colors with disco’s brighter tones.

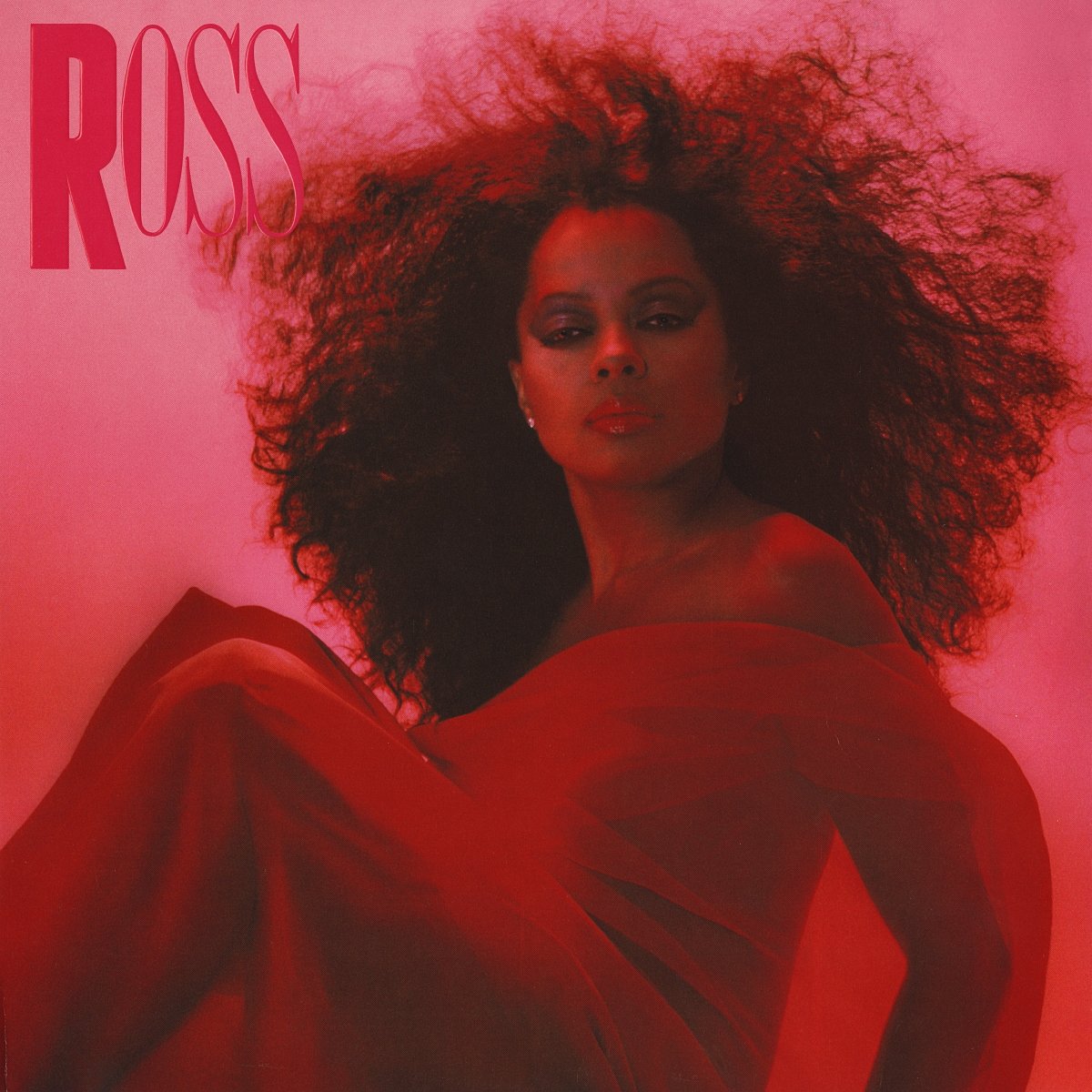

Post-Diana Ross, Baby It’s Me (1977) and Ross (1978) put this mixture of black pop, disco and formal R&B into practice. The former set—with the assistance of producer Richard Perry—struck an inventive balance between these sonics. The latter record flatlined artistically due to it being a “catch-all” for shelved material curated alongside new songs of a subjectively lesser quality. Creative merits of either album aside, they each yielded soft sales.

Ross easily could have set aside making records to pursue further film or television work; the “variety hour” vocation had proven lucrative for Ross’ pop counterpart Cher when her music career encountered sporadic lulls in the ‘70s. Unlike Ms. Sarkisian, Ross’ musical muse wouldn’t let her settle for primetime hostess duties. Accordingly, the vocalist began to conceive of an album—soon to be aptly designated as The Boss—to restore her creatively, critically and commercially. It would also locate that sweet spot between her traditional R&B style and disco.

Listen to the Album:

To ensure a successful execution for this plan of action, Ross reached out to Nickolas Ashford and Valerie Simpson. In addition to their own work as a knockout R&B duo, the husband-wife team were also amazing songwriters and producers too. Their professional relationship with Ross began when they were contracted as producers for The Supremes’ fifteenth LP, Love Child (1968).

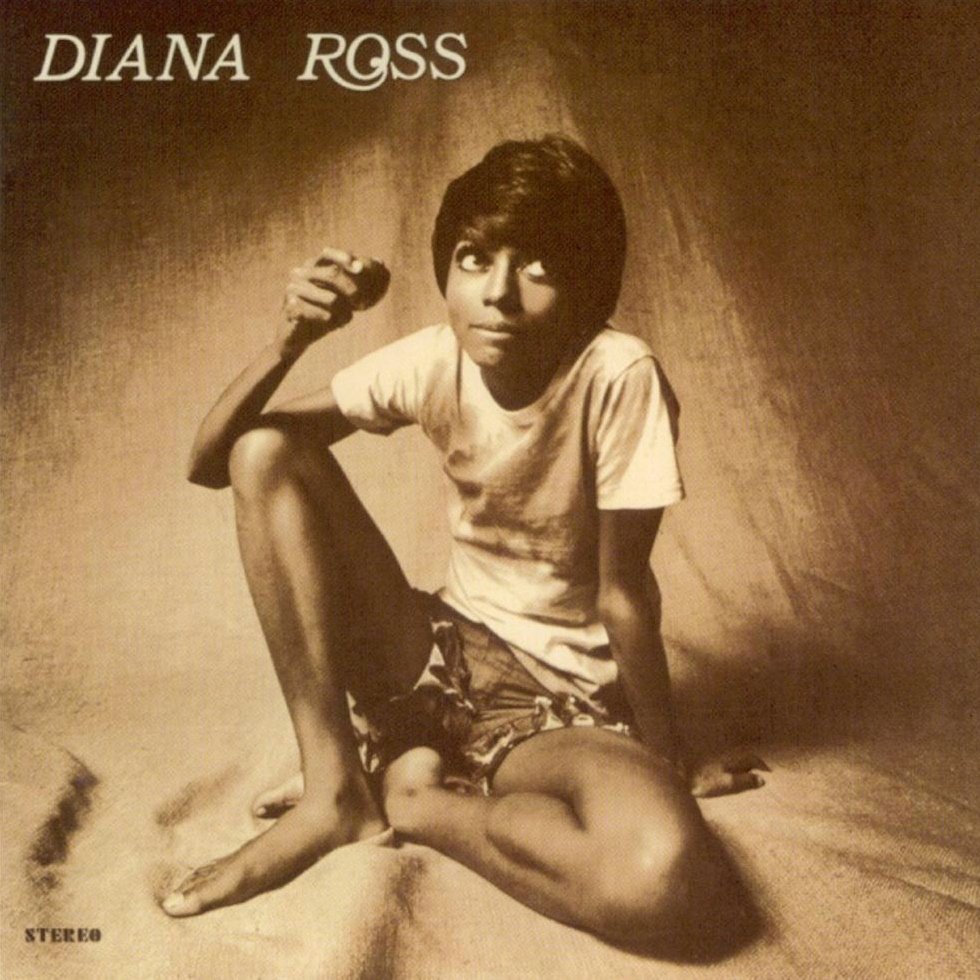

When Ross finally struck out alone, they joined with the former Supreme for Diana Ross (1970) and Surrender (1971), often heralded as Ross’ superlative albums as the songs were tailored to her persona. Ashford & Simpson returned to this same procedure with The Boss—they scripted and produced all eight of the record’s sides that appear on the final product released to the public on May 23, 1979.

“No One Gets the Prize”—a high drama dancefloor piece dripping in brass, bass rhythms and modest digital programming flourishes—opens the long player with a bang. In fine and full vocal form, Ross is a firestorm on “No One Gets the Prize.” While Ashford & Simpson provide solid back-up throughout the record with their own gospel flecked flair, it is Ross who turns in one mesmerizing performance after another on The Boss.

Catwalking through an impressive series of club friendly numbers, their tempos ranging from politely funky (“I Ain’t Been Licked,” “It’s My House”) to feverishly floor-filling (“Once in the Morning,” “The Boss”), Ross displays a joyful and surprisingly authoritative command over the disco aesthetic. On “All for One,” “Sparkle” and “I’m in the World,” Ross indulges in her hallmark balladic appetites; the three selections later became canon highlights for the singer.

The Boss benefits from a robust rhythm section and opulent orchestral accompaniment—courtesy of Ashford & Simpson’s exacting direction—that unify into a striking veld of disco and black pop where Ross can extol her thematic evergreens of romance (“Sparkle”), female empowerment (“I Ain’t Been Licked”) and altruism (“All for One”). Curiously, The Boss is the last Ross record Ashford & Simpson piloted; it can be posited that out of the trio of long players they drafted together, the third entry was their most triumphant.

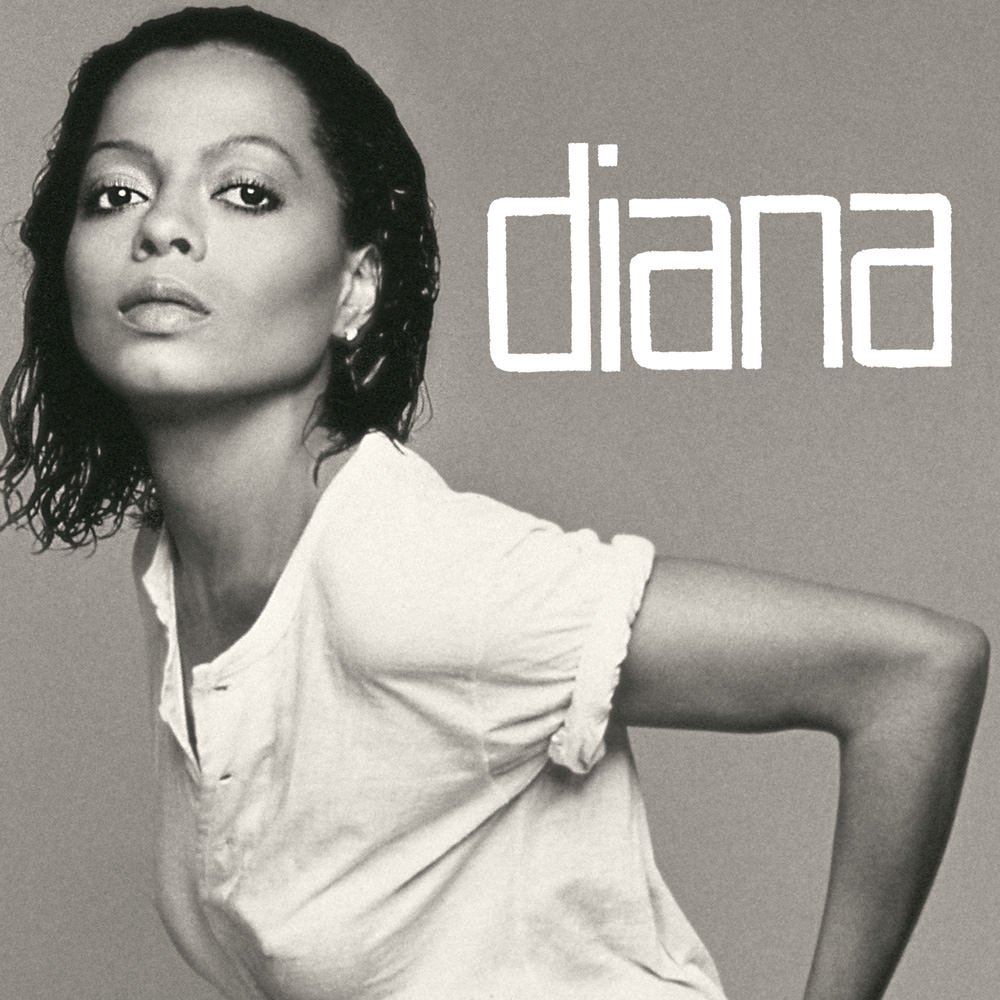

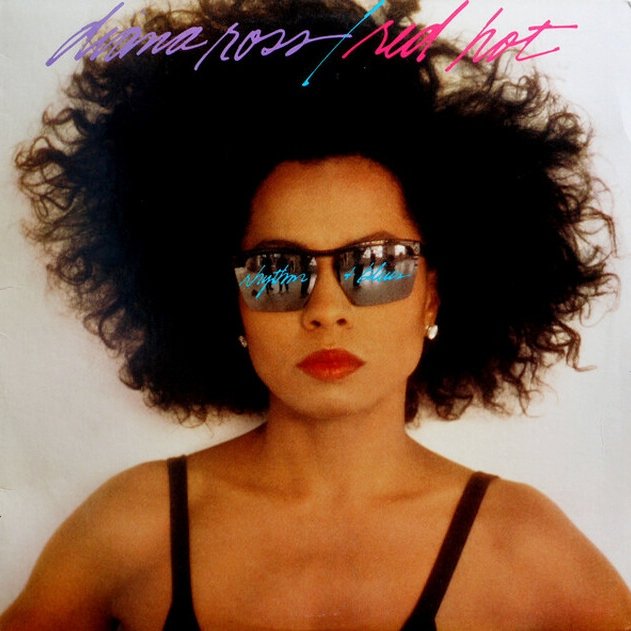

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about Diana Ross:

Representative of an upswing for Ross in all three quarters where she sought restoration—creative, critical and commercial—The Boss was also her first album to successfully employ the dance music method. Three singles— “The Boss,” “No One Gets the Prize” and “It’s My House” —went on to moderate chart gains and, like their parent LP, paved the road for its successor, Diana (1980). The Chic Organization helmed song cycle was clearly modeled after The Boss, although some revisionist historians have tried to reduce the impact of The Boss in favor of championing diana’s more explicit mercantile charms.

But, the agency of The Boss with respect to Ross’ catalog cannot be denied. By accepting disco and making that sound work for her, Ross demonstrated that there was no contemporary genre or commercial trend out of her reach that she couldn’t put into service for her own indomitably innovative will. They don’t call her “the boss” for nothing.

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2019 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.