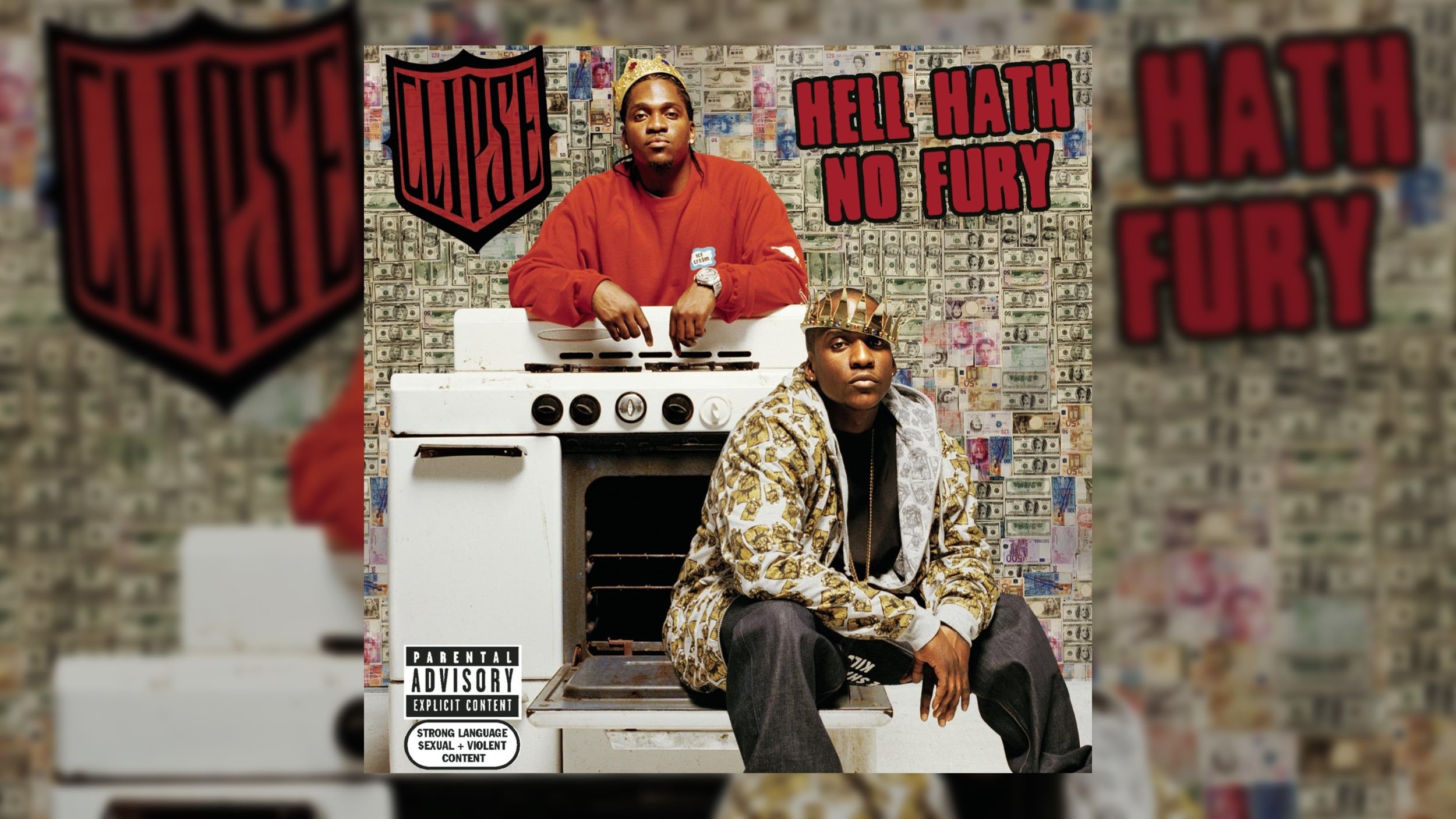

Happy 15th Anniversary to Clipse’s second studio album Hell Hath No Fury, originally released November 28, 2006.

I’ve written about how rappers Ice-T and Scarface pretty much invented the “crime rapper with remorse” genre of hip-hop. Ice-T tended to tackle the legal and societal ramifications of selling drugs in the community, while Scarface made his career delving into the psychological and spiritual toll that doing dirt has on one’s psyche. Both rapped expansively about how criminal activity would significantly decrease one’s lifespan, but Scarface illustrated how these actions could drag one’s soul through mental hell as well.

Clipse come from the Scarface school when it comes to documenting how they’ve struggled with their misdeeds. The duo, comprised of brothers Gene “Malice” and Terrence “Pusha T” Thornton, are deeply religious and have incorporated Christian imagery into their rhymes and videos throughout their career. While the Bronx-born, Virginia Beach-based duo has long rapped about enjoying the spoils of their hustling, there’s always an underpinning of spiritual regret, and the knowledge that they’re someday going to have a reckoning with their Creator. These sentiments are the most apparent on Hell Hath No Fury, released 15 years ago.

The Neptunes production team, made up of Pharrell Williams and Chad Hugo, are integral to the Thornton brothers’ success. Williams had known the pair back when it was just Malice rapping and Pusha had yet to pick up a mic. After a few starts and stops, Clipse released their debut LP Lord Willin’ (2002) through Arista, produced in its entirety by Williams and Hugo. Its success was anchored by “Grindin’,” one of the best singles of the ’00s. They earned nearly Platinum status and vast critical acclaim. But when the group began recording a follow-up, they were met with obstacles that they’d never anticipated.

A big part of Hell Hath No Fury’s legend comes from the labors that Clipse and The Neptunes endured in order to secure its release. The poisonous label politics that occurred between the group and Jive Records shaped the project’s character and sound. I don’t know if a “happy” Clipse would have recorded an album as uncompromised without the adversarial relationship that developed between the pair and the record label.

After the success of Lord Willin’, The Clipse worked to capitalize on their momentum by starting to record their follow-up in late 2003. However, the recording process was put on hold in 2004 while the group worked to untangle their contract situation. During the merger between Sony and BMG, there was a mass shuffling of artists from one label to another label or sub-label now owned by the unwieldly conglomerate. During the ensuing complications, Clipse migrated from Arista Records to Jive/Zomba after the latter “bought” their contract.

Jive in 2004 wasn’t very much like the Jive of the late 1980s and early 1990s. Though the label may have made its name through hip-hop acts like A Tribe Called Quest, Boogie Down Productions and Too $hort, by the late 1990s and early 2000s, they were home to mega pop acts like Britney Spears, Backstreet Boys, and N-SYNC. Seeing that they didn’t fit into the mold of the type of act now signed to Jive, Clipse had hoped to follow The Neptunes, who’s Star Trak imprint was now being distributed through Interscope. However, the label balked, setting up a contentious relationship from the outset.

The duo spent the better part of two years wrangling with the label in order to get Hell Hath No Fury released and filing lawsuits to get out of their four-album contract. In response, the project was met with a seemingly endless procession of delays as Jive and Clipse tried in vain to work things out. All of the drama effected The Neptunes’ relationship with other Jive artists; Pharrell didn’t work with Justin Timberlake for a decade reportedly due to the clashes with the label.

By the time Clipse re-started the recording process, they were collectively in a much darker mood. They were not happy that the momentum they’d built from “Grindin’” and Lord Willin’ had potentially stalled. As a result, much of their sophomore project projects a decisively foreboding tone.

As with Lord Willin’, The Neptunes handle the entirety of the production on Hell Hath No Fury. The Virginia-based duo is well-known for their work across many genres of music. When working with rappers, they’ve done excellent work with Jay-Z, Ol’ Dirty Bastard, Mystikal, Busta Rhymes, Ludacris, and Snoop Dogg. However, they always had the best chemistry with The Clipse.

The Neptunes really outdo themselves on Hell Hath No Fury, as they fit perfectly with Pusha and Malice’s rhymes. Which is strange, because none of the beats featured on Hell Hath No Fury were created for Clipse. In an interview with Complex, Pusha revealed that the tracks were initially offered to Jay-Z for his “comeback” album Kingdom Come (2006). Fortunately for the brothers, Jay-Z passed on all of the beats, and they went “back” to the duo.

The craftmanship for these musical backdrops is transcendent. They’re often seemingly simple, but actually contain great complexity. It speaks to the special chemistry that Clipse and The Neptunes shared, in that many emcees would sound great on nearly every beat on Hell Hath No Fury, but none would ever sound as good as Malice and Pusha.

Malice and Pusha give world-weary but emboldened performances throughout Hell Hath No Fury. They rap unapologetically about both their material riches and the illicit means they used to acquire them. But everything is tinged with a guardedness born of knowing that danger is omnipresent. Pusha and Malice are far from the first emcees to turn selling drugs on record into a subgenre, but they did it better than nearly everyone.

“Momma I’m So Sorry” is emblematic of the themes explored on Hell Hath No Fury, as the duo wrestle with internal conflict over their involvement in the drug game. On one hand, Pusha basks in the success that his extensive engagement in illegal activities has provided, marveling in his own cleverness. On the other, Malice seeks forgiveness from his family for profiting from his misdeeds, hoping to cleanse his conscience by steering the next generation to a better way of living.

This contrasts well with “Hello New World,” in which Pusha and Malice channel Cyrus from The Warriors, delivering a sermon to all of the world’s hustlers and drug dealers, advocating for all to work in unity so that everyone can get rich together. “I ain’t coming at you, quote-unquote famous rapper,” Malice raps. “Who turn positive, try to tell you how to live / But this information, I must pass to the homies / If hustling is a must, be Sosa, not Tony.” It’s a bit nihilistic to hear the two give their full-throated endorsement of selling cocaine as a viable means of getting rich, but the pair traverse this territory with ease.

There’s a run towards the front end of Hell Hath No Fury that features some of the greatest hip-hop released in the 21st century to date. It begins with “Mr. Me Too,” the album’s first single, a rumbling, devious endeavor. Joined by Pharrell on the mic, Pusha and Malice boast about their impeccable lifestyles, and mock those who try to imitate them. “Wanna know the time? Better clock us,” Malice raps. “N****s bite the style from the shoes to the watches / We cloud hoppers, tailored suits like we mobsters / Break down keys into dimes and sell ’em like Gobstoppers.”

With its groaning bassline and drums, “Mr. Me Too” was an unorthodox choice for an initial offering for the album. According to Pusha, they knew Jive wasn’t going to put a lot of effort into promoting the album. Hence, they decided to cater to their hardcore fans. However, when you consider how left-of-center “Grindin’” was for commercially successful hip-hop at the time, you can’t fault the group for following their instincts.

“Wamp Wamp (What It Do)” was another unconventional single and one of Clipse’s top recordings. Malice and Pusha exude both cool and contempt throughout their verses, coming off like a pair of Jimmy “The Gent” Conways. Slim Thug gives a commanding vocal performance, assert imposing authority on the song’s hook. The Neptunes create an all-time great track, manipulating steel drum samples and making congas sound gangsta as fuck.

“Ride Around Shining” is one of the sparsest dedications to rolling around in your ride and expensive timepieces that I’ve ever heard. The track’s stark simplicity contributes to much of its appeal, as The Neptunes sample the intro to classical pianist Nora Orlandi’s “Ode to Bondage #3,” adding in vocal stabs and a thumping drums track. The brothers enlist Ab-Liva for the assist, who’s twisting rhymes wind their way through the track. However, Malice shines the brightest here, as he raps, “Who would've thought such riches stem from ill rhymes? / Canary yellow diamonds size of yield signs.”

Meanwhile, “Keys Open Doors” is one of the few times The Neptunes go for an all-out aural assault with their production, putting together layers of drums, chimes, and percussion, along with ghostly vocals. When paired with Pusha and Malice’s verses, it becomes one of the best rap tracks about selling cocaine ever. “Open the Frigidaire, 25 to life in here,” Pusha raps. “So much white you might think your holy Christ is near / Throw on your Louis V millionaires to kill the glare / Ice trays? Nada, all you'll see is pigeons paired.”

Clipse are joined by Ab-Liva and Sandman on “Ain’t Cha.” The four emcees had collaborated to create the Re-Up Gang and had released a pair of popular mixtapes in the mid-’00s, allowing Clipse to deliver music to their audience while Hell Hath No Fury was delayed. “Ain’t Cha” proves their ability to collaborate over original material, rather than rap over other artists’ instrumentals. All four are in full swagger mode, riding the bouncy track while bragging about their hustling abilities.

With most of the album is devoted to the duo pushing cocaine on the streets, “Chinese New Year” provides an alternative view, with the pair and homie Roscoe P. Coldchain detailing their alleged history committing armed robbery. Pusha’s opening verse is as potent as ever, as he professes to have gone “in and out of homes like the Orkin man.” Later he threatens, “Give up the cash before I turn you Cookie Monster blue!”

Hell Hath No Fury ends with “Nightmares,” their tribute to the Geto Boys’ “Mind Playin’ Tricks On Me.” The song is a gothic hymn to paranoia and fear, anchored by melancholy organ riffs. Here Malice and Pusha are haunted by the lives they’ve taken during their rise to the top of the game. Pusha directly invokes Willie D with his verse, wary that every person that he encounters could well be a potential enemy seeking blood-soaked revenge. “Still, I creep low, thinking n****s trying to harm me,” he raps. “Hoping my karma ain’t coming back here to haunt me / Was it that n***a? I took his powder with a smile / Praying to Lord the gun ain’t pop and hit the child.”

Hell Hath No Fury might not have sold as well as Lord Willin’, but it’s their most overall acclaimed project. In 2007, Clipse reached an agreement with Jive, where the duo was released from their contract. They eventually signed with Columbia, where they’d release what would be their final as album as a group, Til the Casket Drops (2009).

Even I, an avowed “backpack” rap fan, know that Hell Hath No Fury is one of the best albums of the ’00s. The duo’s rhymes hold high entertainment value and depth, and The Neptunes out-do themselves behind the board. Even though so many things went astray while recording this album, the pain of the process can be felt in the music, and it strengthened its core. The duo were fitting heirs to the Scarfaces of the world and soared to similar heights as their role models.

Note: As an Amazon affiliate partner, Albumism may earn commissions from purchases of vinyl records, CDs and digital music featured on our site.

LISTEN via Apple Music | Spotify | YouTube: