Happy 45th Anniversary to Carly Simon’s fifth studio album Playing Possum, originally released April 21, 1975.

“You feel almost as if you’re opening the door on a party that’s already started…”

The line struck me in its succinctness regarding Carly Simon’s fifth album Playing Possum, issued to the record buying public in the spring of 1975. The statement about the set’s inviting mood had come courtesy of Billy Mernit, an accomplished author/songwriter/musician who featured on the long player as a collaborative guest.

Our conversation occurred only a few weeks ahead of the expected deadline for my 45th anniversary retrospective on this largely misunderstood collection. However, as my exchange with Mr. Mernit evinced, there was more to Playing Possum than what was often assumed.

“There is a playful freedom, a sensual sort of a basking in an unrestricted way,” is how Mernit further (and fondly) describes Playing Possum; this artistic abandon hadn’t happened in a vacuum. To understand how Simon arrived at this song cycle, one must go back to where it all began for her musically.

Issued on Kapp Records in 1964, The Simon Sisters – Lucy & Carly—also stylized as Meet the Simon Sisters—was a demure raft of folk-pop from the two siblings who hailed from Riverdale, New York. The beautiful blend of Lucy’s soprano and Carly’s contralto had attracted attention via the LP’s first single “Winkin’, Blinkin’ and Nod.” The handsome adaption of the American writer Eugene Field’s poem “Wynkin’, Blynkin’ and Nod” afforded The Simon Sisters their inaugural flush of modest success.

But, large scale triumph remained just out of their reach. Two more albums followed their debut—one on the Kapp label and another on Columbia Records—with Cuddlebug (1964) and The Simon Sisters Sing the Lobster Quadrille and Other Songs for Children (1969). Neither troubled the charts and the duo amicably disbanded.

Opting not to return to Sarah Lawrence to resume her studies that she’d tabled when things heated up for The Simon Sisters, Carly Simon embarked on a string of odd vocational pursuits: secretary, television handler-hostess, youth camp counselor. As she juggled these various occupations, music was never too far from her mind even if her path toward it wasn’t without obstacles.

It was during her tenure at the Indian Hill Camp in the Berkshires of Western Massachusetts when Simon intersected with two other camp staffers: Jacob Brackman and Billy Mernit. None of them knew it then, but Brackman and Mernit were to play seminal roles in Simon’s personal and professional life.

Mernit speaks warmly of meeting Simon in those early days, “We have been friends since the summer of ’69; I met Carly at a drama and arts camp at Indian Hill. She had been a guitar instructor there and it just so happened that I had sort of fallen in with the same group of friends and people she’d been friendly with (there)—and I kept hearing ‘Wait until you meet Carly!’ We just really loved each other and hit it off and became really good friends.”

Not long after Simon departed the camp, a series of events put her in line to sign a deal with Elektra Records. Once there, she started constructing her eponymous LP Carly Simon. Issued in 1971, the record garnered Simon a “Best New Artist” Grammy Award one year later at the 1972 ceremony. Then, in rapid succession, came Simon’s gold and platinum triumphs: Anticipation (1971), No Secrets (1972) and Hotcakes (1974).

As this was happening, Mernit hadn’t left Simon’s orbit. “Over that period of time when she was becoming ‘Carly Simon,’ so to speak, we continued to be close friends and write together, Mernit recalls. “I played piano on that first album (Carly Simon), I co-wrote some lyrics with her for one of the songs—“Reunions”—in fact, is about that camp (Indian Hill). It’s sort of a personal reflection of that (experience).

“One thing we always did was play each other our latest stuff or sort of compare or talk about lyrics and things like that. The song ‘When You Close Your Eyes’—which is on the No Secrets album—that was a case where she had half of a song basically; one time when I was visiting her in the city, she played it for me, we were both sitting at the piano and she played it as far as she’d gone with it. And she said, ‘Well, this song really needs a bridge and I don’t quite know where to go—it needs some sort of big surprise.’ And I just looked at her and put my hands down on the piano on a chord—that was not in the verse or chorus— and sang ‘big surprise!’ and that actually became the ultimate bridge-change of the song, we went from there. The line that follows is ‘Big surprise, you’ve been informed you’re not asleep’ and it goes on. So, that was the kind of relationship that we had.”

Out of the quartet of records Simon cut from 1971 through to 1974, No Secrets and Hotcakes had been overseen by the same producer, Richard Perry. Perry was instrumental in Simon actualizing her vision of amalgamating album-oriented-rock, folk, country, and R&B tonalities in a vibrant pop fashion.

Lyrically, No Secrets and Hotcakes were also in possession of enthralling character studies and semi-autobiographical pieces—the bulk of which came from Simon’s pen. When the brainstorming for Playing Possum gave way to serious song scripting, Simon requested Perry to return to guide the sessions; he agreed to do so.

Simon understood that it was time to take things to the next level and expound on the ground she covered on her two previous outings; and, as it was on those collections, her real-life courtship with folk hero James Taylor acted as a source of inspiration for this long player too; the two had married in late 1972.

On Playing Possum, Perry provides Simon with an intimate, but luxuriously rhythmic sound that emphasizes melody and groove perfectly synced to her evocative vocalizing. The three-song suite that pulls the curtain back on Playing Possum—“After the Storm,” “Love Out in the Street,” “Look Me in the Eyes”—displays the exquisite effectiveness of this approach. Trimmed in lush string swaths, undulating bass work and spicy percussive touches, these compositions hold fast as Simon’s strongest trio of compositions to initiate any of her albums.

Almost all the rest of Playing Possum stays ensconced in this seductive mold; only the saloon styled funk of “More and More” and the proto-disco of “Attitude Dancing” barely break from Playing Possum’s cool, jazzy vibe. Additionally, these two sides are a testament to the talent gathered to lend their skills in service to Simon. Departed greats Mac Rebennack and Alvin Robinson pen and play on “More and More” and compeer Carole King sings back-up for Simon on “Attitude Dancing”—but the guest list is not limited to Rebennack, Robinson and King. Taylor—singing and playing guitar—and Mernit (on piano) join in too. In fact, Mernit gifts Simon with one of the finest cuts on Playing Possum, “Sons of Summer.”

“When she was recording this album (Playing Possum), she had already heard ‘Sons of Summer’—I had played it for her when I first wrote it. When I played her ‘Sons of Summer,’ she almost immediately said, ‘God, I would love to record that.’ So when she got to Playing Possum, she decided it would be a good song for the record and she very much wanted me to come to L.A. and be the piano player on the track. The only thing I didn’t realize at the time was that it was just going to be me. The decision got made to just have it be (me on) piano and—the loveliest part—Carly creating a ‘chorus’ out of her own double-tracked, triple-tracked vocals, which was just extraordinary. I will always treasure that recording because it’s just the two of us.”

A reflection on youthful days gone by, “Sons of Summer” points to a slight bend in the narrative road for Playing Possum and lays bare the meaning behind the record’s appellation relating to the behavioral pattern used by the possum to throw off predators. Simon herself was eager to “throw off” certain detractors who might try to dismiss Playing Possum as thematically shallow when it was anything but that.

It is true that many of the pieces on Playing Possum are paeans to romance and sensuality as best expressed on “After the Storm” and “Are You Ticklish?” Yet, Simon’s carnality belies an emotional curiosity that can shift the song’s topical tenor when least expected; this allows Simon to balance sex with introspection. “Waterfall” and the title song have Simon exploring her factual union with Taylor on the former and a likely fictional experience on the latter.

And then there is the centerpiece of Playing Possum: “Slave.” Here, Simon addresses the danger of romanticized gender inequity and how women are culturally conditioned to see that imbalance as a state of natural attraction. Some misread Simon’s intent with “Slave” as if she were calling for a normalization of antiquated emotional masochism at the height of second-wave feminism—a movement Simon had more than done her part to empower and advance with her music. This (seemingly) willful misinterpretation of “Slave” was indicative of the mixed reviews that swamped Playing Possum as soon as it landed on store shelves in April of 1975.

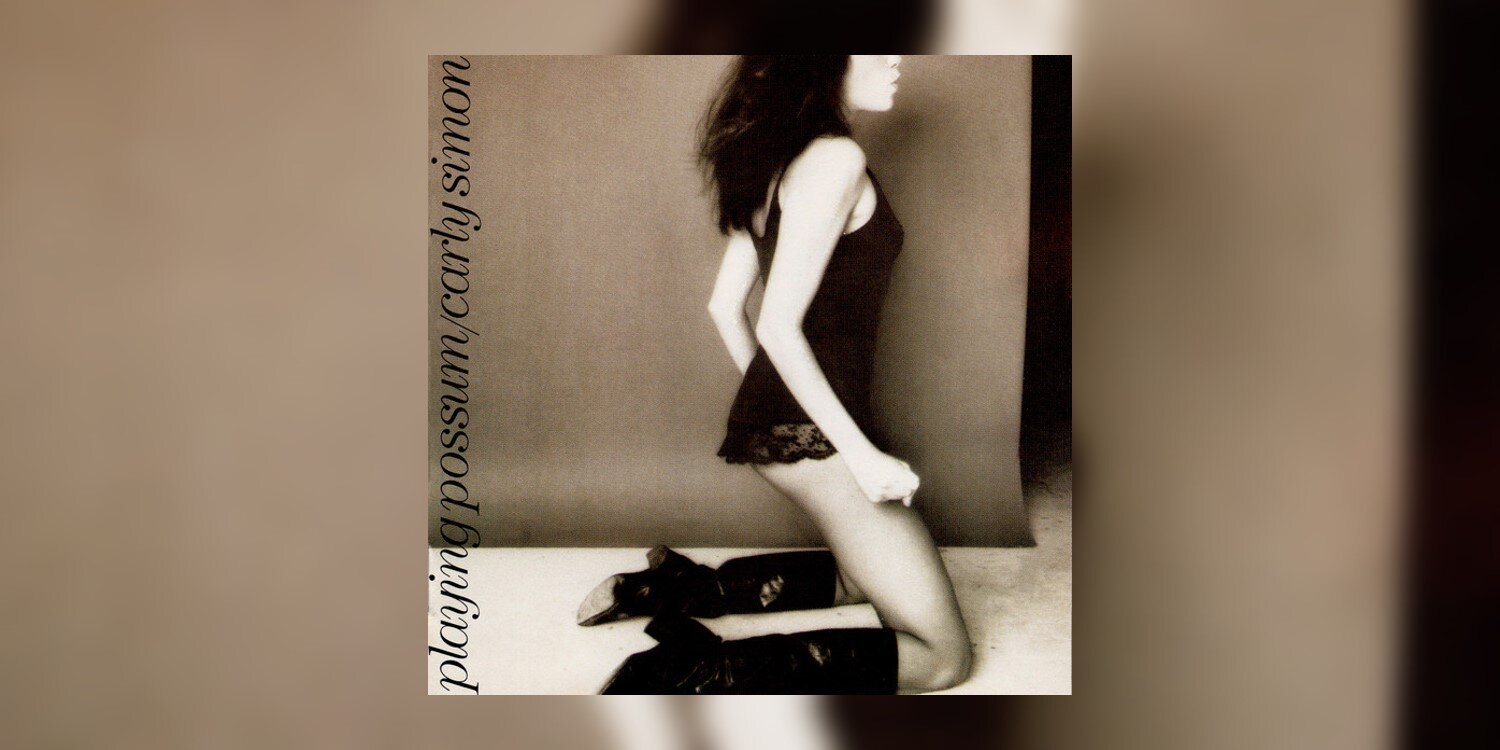

“I was certainly surprised at the time by the reaction,” Mernit confides. “I felt that some of that reaction was oddly in response to the package (cover) from that wonderful photo session she did with Norman Seeff and—my God, did she look glorious or what? The openness that I see (there) is so central to who Carly is as a person—and I think there was kind of a backlash to that. I think there was also a backlash to the ‘celebrity coupling’ of her and James (Taylor) and the success she had had (up to that point).

“How does Playing Possum sound now? I think it sounds great! Obviously I’m prejudiced because I was a part of it, but again, the openness, the warmth, the kind of relaxed feeling of it—I love the way this album opens (on ‘After the Storm’). Those opening chords on the piano…there’s a great feeling of somebody really being comfortable in their body and soul.”

Mernit’s recollection of the critical and commercial drubbing Simon encountered with Playing Possum wasn’t wrong. The effort became Simon’s first individual affair to yield her no RIAA certification. Out of the four singles it produced—“Attitude Dancing,” “Waterfall,” “More and More,” “Love Out in the Street”—only “Attitude Dancing” ended up as a minor charter. Simon did achieve her seventh Grammy Award nomination in 1976 for “Best Album Package.”

At the same time, as Mernit had also rightly observed, the artistic thrust of Playing Possum did have a significantly positive impact on Simon’s canon—then and now. Thumbing her nose at the rigid expectations of the female singer-songwriter model that the popular music intelligentsia tried to force on Simon, she boldly diverted to her own experimental route that ran through the seven albums to emerge in the decade after Playing Possum’s release.

Every record birthed during this expanse was wholly unique and—excusing her groundbreaking covers LP Torch (1981)—her songwriting sat at the heart of each one. While it can never be overstated what Carly Simon’s first four albums did to establish her legend, it was Playing Possum that contributed further levels of complexity and dimension to that legend to ensure its continued endurance.

Read more about Quentin Harrison’s perspective on Carly Simon in his book Record Redux: Carly Simon, available physically and digitally now. Other entries currently available in his ‘Record Redux Series’ include Donna Summer, Madonna and Kylie Minogue. His forthcoming book is a large-scale overhaul of his first book Record Redux: Spice Girls due out in December 2020.

LISTEN: