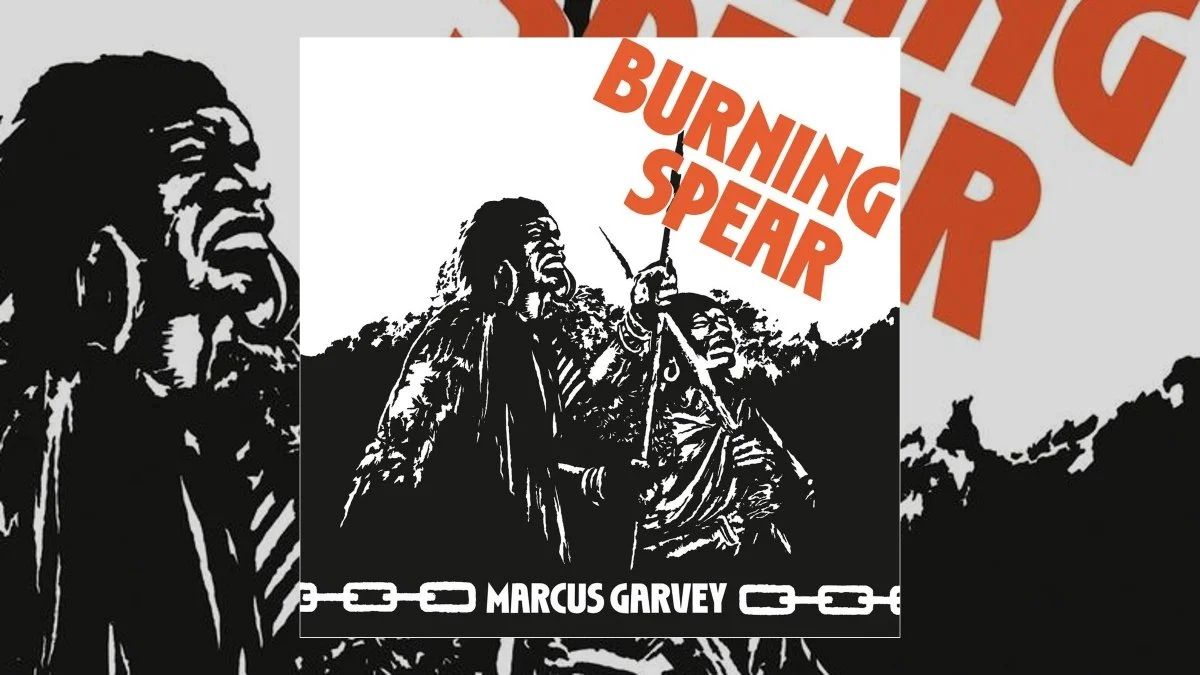

Happy 50th Anniversary to Burning Spear’s third studio album Marcus Garvey, originally released December 12, 1975.

Few genres of music illuminate the juxtaposition of beauty and pain like reggae. Its most prominent artists are like prophets, conveying detailed descriptions of abject poverty, steeped in spiritual imagery. These griots weave anthems of liberation, hoping to inspire the downtrodden Black population throughout the globe, encouraging those to use both action and education as the means to attain freedom. Burning Spear’s Marcus Garvey, released 50 years ago, is such an album. It motivates while creating some of the most exquisite and poetic compositions ever recorded.

These days, Burning Spear is the stage name of Winston Rodney, of Saint Ann’s Bay, Jamaica. But back in the 1970s, Burning Spear was a vocal trio, fronted by Rodney, and backed by Rupert Willington and Delroy Hinds. Rodney first entered the recording business in 1969 and became known for his stunning vocal chops. Bob Marley himself, also a native of Saint Ann’s, advised Rodney to get in contact with the venerable Coxsone Dodd, head of the Studio One label, to explore recording opportunities. The trio recorded a number of singles and a pair of solid albums for Studio One before taking their career, and reggae music, to another level with Marcus Garvey.

A key component to the success of Marcus Garvey is Burning Spear’s collaboration with Lawrence “Jack Ruby” Lindo. Lindo was a record producer and sound system operator known for his distinctive techniques and innovative use of horn arrangements. Unlike most Jamaican music producers, he didn’t operate out of Kingston, instead based in Ocho Rios, which is located on the island’s Northeastern coast. Rodney was encouraged to record with Lindo and his Sound System, and they began working together in short order.

The initial session resulted in what would become Marcus Garvey’s title track. The Jamaican-born Garvey, a Black Nationalist, pioneer in Pan-Africanism, and political activist, was incredibly influential during the first half of the 20th century and considered a hero in his native country. His message of self-determination had resonated not only with Rodney, but also the Black population worldwide.

Listen to the Album:

“Marcus Garvey” was a hit, and the two decided to continue working together. Wishing to continue the recording process, the two soon assembled a full backing band, which Lindo dubbed The Black Disciples. It’s questionable whether they at first intended to release a full project, or just keep churning out singles. Eventually, the group recorded enough material for an album, which they dubbed Marcus Garvey.

The album’s success in Jamaica led to a record deal with Island Records, the label who had brought reggae artists like Marley, Jimmy Cliff, and Toots and the Maytals to a global audience. But the distribution came at a price that infuriated Rodney, Lindo, and the rest of the collaborators. Island had Marcus Garvey remixed without the group’s permission, believing the original recordings were too raw. Hence, they cleaned up the mixes, at times altering the songs’ speed, in hopes of creating a product that was more appealing to white audiences. The label also added a tenth song, “Resting Place,” which the group had previously recorded and released separately as a single.

I personally have never heard the original Jamaican mix of the album and can’t vouch for its superiority. I don’t know if I’ve gotten suckered into enjoying the more palatable version of the album. I can only judge the version of this album that’s been part of my life since I was a sophomore in college, first really getting into reggae via osmosis through a longtime friend. Regardless, I’m in agreement with the pervasive belief the Marcus Garvey is one of the best reggae albums of all time.

On an aesthetic level, Marcus Garvey a perfect album to chill out to. Cool and mellow vibes radiate from the music provided by the Black Disciples and the vocals of Rodney and his cohorts. The lyrics are understated, yet powerful, capturing the sentiments of sections of the population of Jamaica in the mid-1970s. The album is an ode to the philosophies of Garvey, and a call for an awakening, both spiritual and social, for the population of the island and Black people across the globe.

Garvey is a complex individual, but these days his contributions to the ideal of Black empowerment are more widely recognized and celebrated. But a half-century ago, he was beginning to be more widely acknowledged for his impact. Marcus Garvey aims to show how Garvey’s ideas were still applicable to life in Jamaica, and how the population should adopt the spirit of his teachings in order to improve themselves and the island that they called home. At the same time, the content and tone of the lyrics convey a great amount a pain and weariness, echoing the frustration of living in poverty, desperately seeking some measure of peace.

Marcus Garvey begins with the title track, which provides a view of what it was like to live in Jamaica during the mid-1970s, as the country navigated an economic downturn in the second half of the decade. “Marcus Garvey’s words have come to pass,” Rodney intones, describing a country where one “can’t get no food to eat / Can’t get no money to spend.” The intricacies of Lindo’s horn arrangements shine throughout the song, as they drive the song as much as the skanking guitar. A subtle organ solo during the bridge between the second and third verses adds to the song’s complexity.

Using the persistent pain of the country’s past and present to motivate to a better future is the central theme around which Marcus Garvey is built. “Slavery Days” strikes a sharp chord in its description of Africans forced into bondage and forced to work in the sugar plantations through the mid-1800s. Amidst the constant refrain of “Do you remember the days of slavery?”, Rodney depicts visions of the enslaved pulling boats with shackles around their necks, lamenting, “They used us until they refused us.”

“The Invasion” is another potent entry, as he implores Jamaicans to remember and honor their African culture, as colonizers try to rob them of their history. The drum and percussion work on the track stands out, as does Rodney’s extended coda to end the track, riffing seamless streams of thoughts about liberty. “Old Marcus Garvey” features Rodney arguing for Garvey’s recognition alongside more accepted national heroes like William Gordon and William Clarke Alexander Bustamante. It features one of the heaviest grooves on the album, almost masking the force of its message.

“Give Me” addresses the push for independence, as Rodney demands liberation from oppressors, stating, “set me free, let me be free from all misery.” Here the horns are bolstered by a flute solo which run the length of the track. The flute is also featured prominently throughout “Live Good,” with the group expressing a desire to live a virtuous existence. Meanwhile, songs like “Jordan River” and “Tradition” function like hymns, deeply spiritual in their message. The songs feature minimal lyrics, conveying the mood through their musical backdrops. “Jordan River” becomes a solemn meditation, while “Tradition” expresses near boundless joy.

“Resting Place” may not have originally been intended for Marcus Garvey, but it fits in well as the album’s final track. Here the group seeks the solace of a “broad shaded tree” to give them respite from a strenuous existence that’s permeated by “too much pollution.” It’s an apt final statement to cap an album steeped in retelling the physical and psychological pain felt by the global African population.

Burning Spear released a few more albums through Island Records, before going off on his own. One of these releases was Garvey’s Ghost (1976), a dub version of Marcus Garvey, which is spectacular in its right. These days, the albums are often packaged together, and make for outstanding listening experience.

In late 1976, Rodney dissolved “Burning Spear” as a group, and adopted the moniker for himself as an artist. Inspired by his issues with Island remixing Marcus Garvey without his permission, he created the Burning Spear imprint to distribute his music through soon after, which he used to release his music through the mid-2000s, before it morphed into simply Burning Music. Rodney has continued to preach Garvey’s philosophy of self-determination throughout his career, striving to lead by example. And much like Marcus Garvey, he continues to honor the past while looking towards the future.

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2020 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.