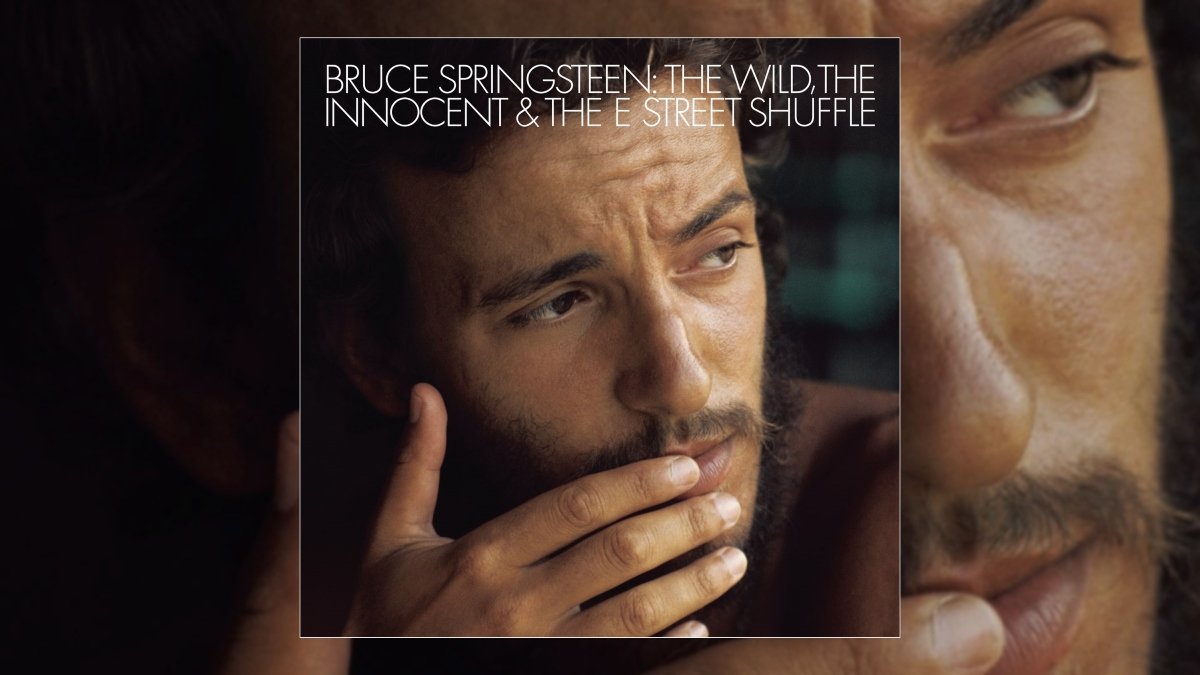

Happy 50th Anniversary to Bruce Springsteen’s second studio album The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle, originally released November 5, 1973.

Most of the listening public seems to think that Bruce Springsteen’s career started in 1975 with Born to Run, peaked with Born in the U.S.A. (1984), and re-emerged decades later when he co-hosted that podcast with Obama. As a result, many excellent records that fail to conform to this narrative—Nebraska (1982), Tunnel of Love (1987), The Rising (2002)—often go unheard by the general public. These links in the chain staying under the radar are why Springsteen’s music is so often misunderstood as artificial populism. This is the stuff that fills in the details and makes it real.

The Wild, The Innocent, and the E Street Shuffle is the skeleton key to the entire operation. Across these seven weird tracks, he ushers you through a dream world with complete sincerity. At age twenty-four, he was already looking back on halcyon teenaged days, a boardwalk world that had already dissolved or rendered itself unrecognizable to him. The Wild, The Innocent, and the E Street Shuffle is a way to fix these elusive memories into physical form, so that they can always live somewhere. It’s not a performance of anything—it’s an accounting.

But the documentation is not stable. Like Tony Soprano’s fever dreams on the same boardwalk, The Wild, The Innocent, and the E Street Shuffle frays at the edges. “Wild Billy’s Circus Story” is the most out-there track of them all, bringing in a caravan with the flying Zambinis, dancing elephants, and a nefarious circus boss who threatens to lure the young Springsteen to the next town. It’s obviously a coincidence that the circus’ next stop is Nebraska—a state whose devastated position in Springsteen lore wouldn’t be established for nearly a decade—but does suggest that there is a darkness lurking just around the bend.

The other notable moment of true instability is “New York City Serenade.” After a surprise and impassioned breakdown, the song’s final verse plays fast and loose with the melody, transforming slowly over the course of its run. Eventually, the instruments fall out of time completely as reality itself begins to collapse. Springsteen whispers “listen to your junk man” as things fall apart, but the ship rights itself all of a sudden with the “he’s singing” epilogue. Of course, if the junk man is singing, he must have found quite a score—maybe the boardwalk itself has fallen into his clutches, to be repurposed into something else. Springsteen’s vocals become unintelligible, Clarence Clemons wails on the sax, and the last thing we hear is a twinkle of David Sancious’ piano over a nostalgic string orchestra. We wake from the dream, in an early-morning haze that would be continued two years later with the opening notes of “Thunder Road.”

Listen to the Album:

To love The Wild, The Innocent, and the E Street Shuffle is to be willing to abandon the straightforward world that defines the rest of Springsteen’s career. On the later records, we’re told that open roads hold promise, bosses hold us back, and a good night of rock & roll is all you need to find salvation.

But at the circus, there’s no clean cause and effect, no concept of departure (except on “Rosalita (Come Out Tonight)”). The world just is what it is and threatens to flutter away in the breeze at any moment; Springsteen just sounds like he’s trying to get it all on paper as quickly as he can. It’s all fleeting, so the rhythms bounce in a slipshod way and the band has to warm up at the beginning of the first song.

Which is not to say that The Wild, The Innocent, and the E Street Shuffle is an experimental record by any means—especially not by the standards of 1973. There’s quite a lot of rough-and-tumble rock & roll on this record, with the infectious groove of “The E Street Shuffle,” the slinking tour de force of “Kitty’s Back,” and Springsteen’s titanic monument to the concept of youthful foolishness, “Rosalita (Come Out Tonight).”

What makes these rock tracks notable, and distinct, from other bangers in the Springsteen canon like “Bobby Jean” or “Badlands” is perspective. Before Springsteen got anthemic, cinematic, and most importantly, self-aware, he was peddling these shaggy tales of boardwalk romance that didn’t seem to go anywhere. On Darkness on the Edge of Town (1978), he critiqued the promise of ever getting out of your small town. On Born to Run, he rendered that promise into cinematic, maximalist form. On The Wild, The Innocent, and the E Street Shuffle, he just lived it.

This is what makes the album’s status as a collection of unaware hallucinations so compelling. Springsteen merely captured a world that was fragile and unstable, because he was inside of it. The strangeness of this record is not a simulacrum of the scene or the sound, it simply is the scene and the sound. If you were trying to make a concept album about this scene, you’d make something like The River (1980): a collection of zippy, three-minute bar band tunes interspersed with the occasional eulogy. You wouldn’t write seven meandering tunes, all of which reach four-and-a-half minutes and most of which crack seven. But this is not a concept album. It’s just The Wild, The Innocent, and the E Street Shuffle.

Listen: