Happy 45th Anniversary to the Bee Gees’ fifteenth studio album Spirits Having Flown, originally released February 5, 1979.

When the Bee Gees and their co-producers Albhy Galuten and Karl Richardson regrouped at Miami’s Criteria Recording Studios in March 1978 to begin work on the band’s fifteenth studio album, the commercial heat of the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack was still at a magmatic boil, particularly in the United States.

The album had reached number one on the Billboard Top 200 in late January and would remain in that place for an astonishing twenty-four consecutive weeks. The Gibbs’ third single release, “Night Fever,” reached number one in the latter part of the month and become their third single in a row to top the chart in less than three months. The Bee Gees’ singles from the soundtrack alone accounted for fifteen weeks at the summit of Billboard’s Hot 100 in a twenty-week span from December 24, 1977 through May 13, 1978.

True to their character as consummate songsmiths, the Bee Gees renounced the opportunity to bask in their grandeur in favor of buckling down and writing their next chapter. Eleven months later, they surfaced with Spirits Having Flown—their most complex and ambitious album to date.

The success of Saturday Night Fever was all at once magnificent and alarming, an experience Barry Gibb would years later compare to the sustained force of a hurricane. The four songs the Gibbs somewhat reluctantly contributed to the film out of obligation to their manager, Robert Stigwood, were not only hits—they became the unintentional propellers of a massive societal shift. Fever thrust the images and sounds of a long-existing “disco” subculture created by, and for, the marginalized working class into a global spotlight, and, by association, the Bee Gees’ universally appealing music was the score of its explosive transition from East Coast respite to fashionable global phenomenon.

Fever’s impact loomed large as Barry, Robin, Maurice, Galuten, Richardson, and established bandmates Blue Weaver (piano and keyboards), Dennis Bryon (drums), and Alan Kendall (guitar) prepared to ensconce themselves at Criteria for the next eight months to create Spirits Having Flown. The songs that comprised the now infamous first side of the soundtrack album were more than just monumental hits—they were game-changing recordings from a technical perspective that had stretched them immeasurably as singers, writers, and producers. Public expectations would be high, although they seemed to be equally so among the Gibbs and their associates.

“We had to live up to this standard, this bar, we’d set,” Richardson tells me during a recent conference call, with Galuten also on the line. “There was some talk about, ‘okay, we just can’t let anything go out that isn’t higher than this bar.’ And that was the dedication of the project. Nothing went out the door without the complete approval of everybody all the way around. Only after the mixes were in the can did we feel, like, ‘oh, we finally got [there]. We raised the bar high enough.’ We didn’t talk about it that much because it was so fun doing it, but we knew there was that thing of...not pressure so much, but we weren’t going to let it go until it was right.”

Although the focus was inarguably on quality, Galuten insists the team’s virtually flawless track record instilled a level of confidence that their efforts would inevitably pay off. “We were no longer saying, ‘I wonder if this is a hit,’ but rather, ‘I wonder how many weeks at number one this will be?’”

With Spirits Having Flown, the Bee Gees usurped the creative control that had been tugged away from them after their last studio album, 1976’s Children of the World. Fever wasn’t their vision, nor was the woefully misguided turn they were impelled to take as a Beatles cover band in yet another Stigwood-helmed film, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The Gibbs and their co-producers agreed that the new album needed to take a calculated step away from its predecessors.

“We knew it wasn’t going to be dance music so much,” Richardson reveals. “It was more like a direction, a consciousness. The R&B was always there, and that was Barry’s right hand. He’d pick up the acoustic guitar and made those rhythms from the get-go. We had drifted away from the dark side of discotheque, because that whole era—and we’d had great success with ‘You Should Be Dancing’ and things like that—it became a little bit more of an art form to make records rather than just a groove. It was a conscious decision by all of us in the control room.”

For the first time in their twenty years together as a group, the Bee Gees’ positionality afforded them the resources to create and experiment in ways that hadn’t existed previously. What resulted is considered by many to be a masterclass in album production.

Robin Gibb’s son, Spencer, who has worked in the industry for years as an engineer, producer, and singer-songwriter, agrees that Spirits is the pinnacle of the Bee Gees’ recorded works.

“Sonically, it’s probably the most perfect record the brothers ever made,” he shares during a recent phone conversation from his studio in Austin. “That’s certainly not to demean anything else that came later or before. You had this crew of people—the brothers, Karl and Albhy, and the band members, Alan, Blue, and Dennis—that had been doing this together for a few years at this point, and they were basically the tightest they’d ever been.”

The Bee Gees’ sound on Spirits Having Flown is an evolution of the soulful flavors they unearthed for Main Course, which had pulled them out of demi-obscurity in the middle of the decade. Barry’s powerful and agile falsetto voice, which fueled the energy of Fever’s up-tempo arsenal (“Stayin’ Alive,” “Night Fever,” and “More Than A Woman”) became the focal point, and the production team explored every possible nuance it could offer. The mortar for the project is, of course, the Gibbs’ harmony singing, which is performed with a level of precision that other vocal groups could only hope to achieve through studio trickery.

Listen to the Album:

The album’s first single, the gorgeous, soaring “Too Much Heaven,” arrived ahead of the album in November 1978. Employing a full orchestra, including audible flugelhorn and flute by Chicago founding members Lee Loughnane and Walt Parazaider, the arrangement evokes some of the Bee Gees’ late ‘60s ballads that were flush with swells of strings and horns. The track’s unusual bass line punch, which at points sounds almost as if it’s off-pitch, gives it a decidedly R&B movement as it edges forward.

The Gibbs’ vocals on “Too Much Heaven” achieve a pristine depth and unity that it almost sounds electronically processed. What you’re actually hearing, according to Galuten, is a cascade of note-perfect takes that capture just how uncommonly good they were as singers.

“I remember Barry never listened to other vocals when he was singing his background tracks, he explains. “I don’t think he had to do a second take on any of them. And then we put them up, and they were all absolutely on time together, every breath together, every vibrato—everything in tune.”

“Yeah, it was breathing tremolo,” Richardson adds. “You know, [mimicking] ‘ahh-ha-ha-ha.’ And he would pace them according to the rhythm of the tune. And you’re right, he wasn’t hearing any of the background vocals—in fact, any of the vocals we did with the Gibbs, we never played them any of the tracks in the headphones. It was all just raw.”

Spencer endorses Galuten and Richardson’s observations. “If you listen to [“Too Much Heaven”] as an arrangement, especially from a producer’s perspective, what is unique is that because you have the orchestra underneath and minimal other instrumentation, the vocals might as well be a choir with the orchestra. It’s so lush and textured together. I had the opportunity to be in the studio with them many, many times, and the way they knew each other was just fucking creepy. My dad would be doing a vocal take and Barry would be sitting at the console, and what I’d hear was something magical. And Barry was like, ‘ahh...no. You’re flat.’ And I’m like, ‘no, he fucking wasn’t!’ And I have a good ear. My dad would say, ‘okay,’ and then he’d sing again, and it would be just slightly more perfect. Not much, to my ear, but then Barry would say, ‘okay, perfect. You’ve got it.’

And then Barry would go in and my dad would produce him, and it’d be the same thing. They could just hear shit in each other’s voices that nobody else could, and that was just a part of being brothers and growing up together. My dad and Barry would often sing a lead vocal together and it would sound like one voice.”

All told, “Too Much Heaven” incorporated twenty-one vocal tracks into the final mix. Advances in recording technology toward the end of the 1970s gave the production team a greater range of options to work with as they toyed with arrangements in the studio.

“There were three tracks of Barry on each of three parts in two octaves, so that’s eighteen tracks of Barry,” Galuten recalls. “Then three tracks of the three brothers singing together. I remember we did three of the tracks, since we were tripling everything, with the three of them singing just to sort of add the rougher edge because Barry’s were almost too perfect. George Terry played the guitar part—I guess it was a Leslie guitar [mimicking the tune] ‘da-da-dah-da-dow-doo.’ And Jimmy Pankow used the Chicago horns on that song.”

“Yes, yes. Because they were next door,” Richardson interjects. “We went into [Criteria’s] little Studio D, and we overdubbed [there], but we kept Studio C open as well. We were running back and forth, if I remember correctly. The album was recorded mostly in Studio C, but it was mixed in D, along with some overdubs.

We had forty-eight-track machines for Spirits Having Flown [using] a thing called a mag sync, and it was designed to do audio-to-film, but we used it as dueling twenty-four-tracks to make forty-eight. There was a pause where you had to wait for one machine to catch up to the other and it would finally lock in. Mixing was a little bit more tedious than recording because we were using slave reels where we had a basic cue mix on a twenty-four-track tape, and then you could do eighteen tracks of vocals and not think anything about it because those eighteen would get bounced down to one pair or two pairs, or whatever. On the master slave, it was a forty-eight-track mix, eventually—and you may not have used all forty-eight, but you certainly had the luxury. The idea was that you could control how much harmony on the chorus was actually audible.”

“Too Much Heaven” gave audiences their first taste of what they could expect from the highly anticipated Spirits Having Flown. After an impressive debut of number 35 on the Billboard Hot 100 on November 18, 1978, the single reached number one seven weeks later on January 6, 1979.

The Gibbs had committed all royalties in perpetuity from “Too Much Heaven” to benefit UNICEF’s world hunger programs, which reportedly had amounted to more than seven million dollars by 2003. The Bee Gees, Andy Gibb, ABBA, Olivia Newton-John, among others, participated in the Music for UNICEF Concert: A Gift of Song, which was broadcast by NBC on January 10, 1979, where they performed their current number one single live at the United Nations General Assembly in New York.

Although penned by Barry and recorded two years earlier during the sessions for Children of the World, the country-infused “Rest Your Love On Me” deserves mention as the chosen B-side of the “Too Much Heaven” single. The song gained enough traction at country radio to earn them a top forty hit on Billboard’s Hot Country Songs, peaking at number 39 on January 13, 1979. The song would be resurrected by The Osmonds later that year, and then on Andy Gibb’s After Dark as a duet with Olivia Newton-John. In 1981, Conway Twitty would record his own version that would reach number one on the country charts.

“Barry wrote the lyrics to ‘Rest Your Love On Me’ live on the mike,” Galuten remembers. “Stephen Stills was playing bass, and Barry was on the mike and just, literally, made up the words to [it] on the fly.”

Spirits Having Flown’s next single, “Tragedy,” made a strong impression before it was even on tape. “We went over to the beach house, and Robin and Maurice were there, and Barry had his acoustic guitar,” Richardson reminisces. “And they did [it] live, a cappella, with the guitar for Albhy and me before we’d even committed it to the album. [We] looked at each other and were just, like, ‘well, that’s obvious.’

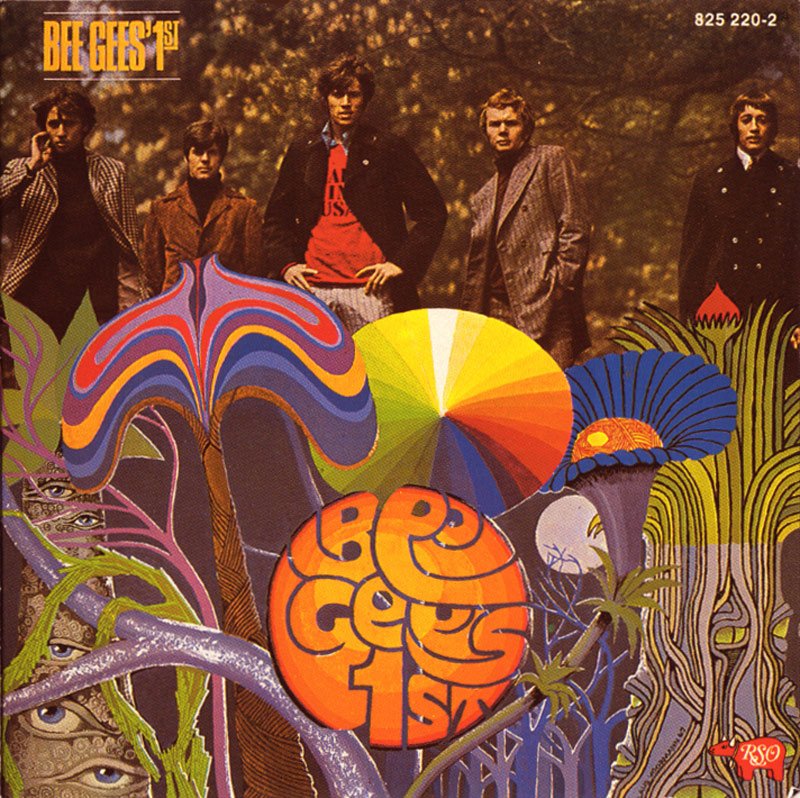

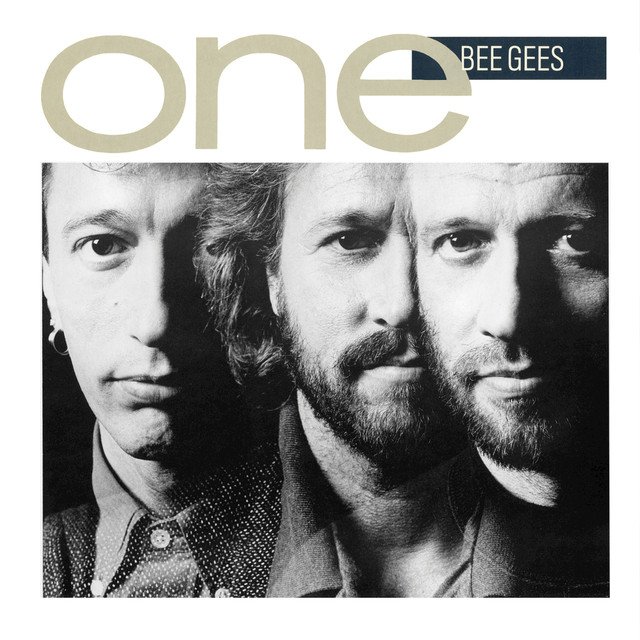

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about the Bee Gees:

I remember Barry used to sit on his couch and he would thumb around on his acoustic guitar and write songs in real time. He would have melodies and stuff kicking around and some semblance of lyrics or phrases, but he had the ability to compose in real time. And when you see that happening in front of you, live, it’s really an amazing thing.”

The dark pulse of “Tragedy” is unlike any previous Gibb composition—not even the solemn survivalist edge of “Stayin’ Alive” seems as passionately urgent. The protagonist is in agony, ("Here I lie in a lost and lonely part of town / held in time, in a world of tears I slowly drown"), and each keystroke, drum beat, and vocal phrase communicates their struggle with escalating clarity.

The intricate network of synths that chatter incessantly underneath the melody line are fascinating to deconstruct over multiple listens, as are the macabre waves of horns that crash over the chorus, almost like cinematic sound effects that would personify the presence of a villain suspiciously entering a scene. Sure, “Tragedy” might be danceable, but its theatrics borrow just as heavily from stadium and glam rock. U2’s Bono is just one of many artists who have complimented its genius.

The explosion at the song’s climax has been the subject of much interest, and footage filmed at Criteria that aired in a Bee Gees special on NBC later in 1979 documented a session with Barry in front of a studio microphone blowing through his cupped hands to achieve the effect.

Richardson describes how they processed that raw sound to give it more authenticity. “It was a thing called a product generator. It was a new toy that someone...you know, we were in tune with all the [Audio Engineering Society] shows—you know, ‘what’s the new stuff coming out?’ And I guess we just got a sample of it. It was a box and you put two inputs in it, and it generates all these harmonics and products.

So, the two things that went into it were Albhy, or maybe Blue, holding the notes on the bottom end of a piano across multiple keys—maybe as many keys as you could mash down on a grand piano—and then Barry’s voice going ‘pbbhhhh!’ into a dynamic microphone, blowing air through the diaphragm to distort it. And then you mix these two signals through the generator, and whatever came out sounded like dynamite [laughs]. It was very technological—nobody had that sound, I know that for a fact.”

The team spent hours in the studio pushing the limits of new gadgets and techniques. "[Spirits] was our first real flexibility to have multiple tracks that we could plan on and put together,” Galuten explains. “And we had a click [track] that we could use to drive a sequencer. I remember on ‘Tragedy,’ the bass drum was a noise generator from the sequencer, and we had all these sequenced parts from an Arp. It was a little box that had sixteen sort of de-tented faders—one for each sixteenth note. And you could set the pitch on each note and then program the sound, and it would play them following the click, and then we’d delay the click so it would come out on time. So, if you listen to ‘Tragedy,’ there’s all these sequenced things, and the bass drum part was a synthesizer that might have been the first thing we laid down.”

Richardson adds: “I remember the big [synth] pads, though [mimicking the intro on ‘Tragedy’] ‘dah-daahh-daaahhh, dah-daahh-daaahhh...,’ you know, all those...”

“That was a sawtooth [wave],” Galuten confirms. “Three waveforms slightly out of tune so they would beat nicely. It was sort of one of my classic sounds that I used to use.”

“We had all kinds of stuff,” Richardson continues. “There were Moogs and Arp synthesizers. There was a lot of stuff that nobody got to hear because we tried a lot of things, and we were very much in experimental mode because we had the freedom. We knew that the budgets weren’t the issue—it was creativity and getting it right. And we went to a great extent to get it right because we knew that hit records...they last for a long, long time, and once you put it out there, that’s what you put out.”

The boldness of “Tragedy” resonated loudly with record buyers. It rose to number one on the Billboard Hot 100 on March 24, 1979, and achieved the same position in the UK, Ireland, Spain, Canada, Italy, and France. It was the Bee Gees’ fifth consecutive number one single in the United States.

The third single from the album was the funkier “Love You Inside Out,” which would also be the Gibbs’ third consecutive number one hit from the album when it reached the top of the Billboard Hot 100 on June 9, 1979. It also tied the Bee Gees with the Beatles for the chart’s record of six total consecutive number one singles, inclusive of the previous three they’d scored with Saturday Night Fever’s “How Deep Is Your Love,” “Stayin’ Alive,” and “Night Fever.”

“From a songwriting perspective, ‘Love You Inside Out’ is very unique and very bizarre,” Spencer points out. “The chorus-verse-bridge structure is all jacked up.”

It’s an accurate description, as the song bounces dramatically between downtempo and midtempo passages, ramping up to a near-manic break just past its halfway point before it returns to the refrain for the last minute of its duration. In some ways, it’s similar to Andy’s “(Love Is) Thicker Than Water” in a compositional sense, which was also slightly out of character structurally for Gibb songs of the period. Nonetheless, it’s a fantastic piece of pop.

“'Love You Inside Out’ had the Leslie [amped] piano, that [mimicking] ‘dah-dun-dah-dah-dun-dun'—the low grand piano part,” offers Galuten.

“That was a great R&B feel, too,” says Richardson. “The rhythm and blues on that record just when you think about how the groove worked...I remember Michael Jackson came back to us and said, ‘you know, that’s one of my favorite records to play.’”

Post-Spirits, “Love You Inside Out” received an excellent cover treatment from Canadian singer-songwriter Feist (titled “Inside And Out”) on her 2004 album Let It Die, accumulating robust radio play in North America the following year when it was released as a single. Snoop Dogg sampled it prominently on his 2005 single “Ups & Downs.”

The balance of Spirits Having Flown that didn’t see wide release as singles are unmined gems that have been long underappreciated for their diversity and caliber. “Reaching Out,” with its finger-picked acoustic guitar undercurrent, showcases the Gibbs’ consistent ability to write and sing ballads that balance sensitivity and intensity. "[It] sounds like one of those classic Philadelphia R&B tracks,” Galuten observes. “It’s like, ‘oh, this could have been a Spinners hit.’”

“Stop (Think Again)” is more deliberately blues-hued, challenging Barry as lead vocalist to navigate a tricky time signature and a markedly different soundscape than much of anything the band had produced to date. Over the course of the song’s six minutes and forty-one seconds, the range of feeling he’s able to illustrate with his voice allows you to appreciate the truly unique instrument the Bee Gees had at their disposal—quite literally at points where it matches the rasp and sear of Gary Brown’s thick saxophone solo.

The track also posed a set of interesting obstacles in the control booth. “’Stop (Think Again)’ is a great song,” Galuten declares. “It’s like a B.B. King song—just a great slow blues ballad and a fantastic song that should be covered by somebody. But I remember it was the most tape edits I think ever done on one track in the world. It was a very slow tempo and it was very hard to play, and we finally got a take that we thought had all the right dynamics and the right feel. It sort of moved around a lot in time, and so Karl would...I don’t know, I remember there must have been a hundred, hundred-and-fifty splices in it.

Taking time out [of the track] was easy. Putting time in meant that it needed the ambience, so he had little bits of tape all over the wall with markings on them, like, that this [splice] had the ‘right overhead at minus twenty.’ And when we needed [that], he’d find the right piece with the tape on it and splice it in.”

“What was interesting was that it was two-inch-wide tape, so when you put it in the splicing block, you’re slicing it at an angle,” Richardson expounds. “And some of the slices were about three-eighths of an inch, so, basically, you’re taking out a very, very small amount of time, hand-splicing tape, which was a very physical process. The master, because it was two-inches wide, I played it and recorded it on another machine, and I called it a dumb master because you weren’t going overdub with all these splices flying through the heads. It was a mechanical marvel. And the song wasn’t in 4/4 [time], it was in 12/8 or something, which was funny. But we got through it.”

“Search, Find,” which opens the album’s second side, is buoyed by the dexterous bass work of session veteran Harold Cowart, and sparkling ribbons of horns and strings chase the rhythmic bounce of the choruses: (“Search...find / no stone unturned, no hell, no fury gonna stop my love and all its glory”) It could have easily been a fourth single.

“I’m Satisfied,” featuring legendary jazz/world music flautist Herbie Mann, is cut from the same cloth, although its groove is slowed down a few steps. The countermelodic interplay in the latter half is fun and frolicsome, again demonstrating how adeptly the Gibbs used their voices to create texture and dimension.

Tucked away on the album’s second side is “Living Together,” arguably one of the most interesting pieces of ear candy they crafted during this period. Opening with a full symphonic, Beethoven-esque overture, it escalates into a waft of strings before it dissolves into a low synth hit and transitions into a satisfying funk shuffle. The refrains break twice and fold into verses with Robin’s lead vocal, which is a startling, and quite wonderful, contrast to Barry’s.

“[It] really showcases my dad’s crazy falsetto. It’s nuts,” Spencer muses. “Spirits was one of the first Bee Gees records that didn’t feature my dad heavily on lead vocals. And I wish there had been more of that. It’s my only real criticism of it.

If you take a look at the ‘60s, in many respects – or even most respects – my dad was the voice of the Bee Gees. In the ‘70s, Barry became the voice. And by the time they got to Spirits...my dad had sung lead on a lot of tracks on Children of the World, and Saturday Night Fever wasn’t backing away from that specifically, there were other songs he sang on that they didn’t get to finish before they submitted stuff for [the film].

There was a big preoccupation with having hits, there was a big preoccupation with having a cohesive sound, and I think that my dad kind of took a back seat vocally in terms of leads because they wanted that cohesive sound, they wanted the hits.”

The album’s beautiful title track diverts from R&B and instead embraces a sparser Afro-Caribbean vibe with acoustic guitars, congas, and woodwinds, relying on Barry’s natural voice to meander through the verses and falsetto harmonies to push the choruses skyward. The song’s outro after the second chorus is a lengthy extrapolation of the instrumental break after the first, gradually incorporating swirls of strings that Barry and Albhy had composed together.

“I’m really happy with a lot of the orchestrations on that song,” Galuten affirms. “We did the strings in Miami and, so, it was a fair amount of work because they’re not like the New York or L.A. string players—not the same kind of experience. But we had time, so we spent more time with them and got all the pieces really right. And the Boneroo Horns and all of the parts were just well-put-together around the vocals and the arrangements for the song. I was just very pleased with how it came out.

It was, again, where Barry and I were kind of firing on all cylinders. I would go to his house and we would play a cassette, and we would sing the parts to each other and I’d write them down and then orchestrate them. And it was a lot of, again coming back to that theme, the confidence that if he could hear something in his head, he knew we could get it onto tape.”

While “Spirits (Having Flown)” was not released as a single connected to its parent album, it was pushed out to markets outside North America to promote the Bee Gees Greatest compilation that arrived later in 1979. It resulted in a UK top twenty hit in early 1980—the last one the Bee Gees would have in their motherland until 1987.

An eleventh track, the excellent “Desire,” had been worked on and then dropped from the lineup after several weeks. The completed version was eventually added to Andy’s After Dark album, where his lead was substituted for Barry’s. But all the background vocals and instrumentation that had been recorded during the original Spirits sessions remained intact. Released as After Dark’s first single, it reached number 4 on the Billboard Hot 100 in March 1980.

Closing the album was the short, minimal ballad “Until,” which again exerted Barry’s natural voice backed by flourishes of spacey synths and a little string sweetening.

“It was spontaneous in the studio,” Blue Weaver recollects in an email we exchanged recently. “I was programming the Yamaha CS-80 for another song when I started playing around with that sound. Barry came in and started to sing and within about thirty minutes we had put down the synth and most of the vocal ideas. It was a perfect track to end the album with and such an emotional performance.”

That so many of the pivotal moments on Spirits Having Flown revolved around Barry’s prominence has led to lengthy debates among fans about what opportunities Robin and Maurice were given to contribute throughout its conception.

“[Barry] was at the peak of his creative ability,” says Galuten. “He was writing up a storm and his singing was great. He always lived in the studio, so he was there the whole time. Robin and Maurice would come in and go out as we were working on things, as would the band members, but Barry was there almost twenty-four-seven.

It was not like we sat down and made a decision, ‘oh, let’s make this a Barry record.’ He would just do stuff and he would come out and it would be amazing, and everyone would go, ‘okay, well that’s fantastic!’ And then you would try something else, maybe, and it wouldn’t be as good. As a result of him being in such a creative place and that we were all working together so well, his ideas would just happen.”

“Also, I think the three of us were all in sync,” explains Richardson. “We didn’t really need to talk too much because we used eye contact. Frankly, it was hilarious. We would sit in the control room and pretty much never stop laughing. The idea of how pleasant of a recording experience this all was. You know, you hear stories about sessions where people are arguing and going crazy. These were all the opposite of that—it was joy. We couldn’t wait to keep going.”

“One of the things I feel about Spirits that was so special was that they had the freedom to be very much themselves,” Spencer articulates. “The brothers always hated being referred to as disco, because in their minds, they weren’t—they were R&B. And sometimes even a little political. I never considered them to be disco. In the ‘70s, Michael Jackson was very disco, and Donna Summer—everything had all these little blips and bloops. The brothers were darker.

And Spirits is not a disco record, under any circumstances. At all. If anything, it’s the most intentional record they made since Odessa.”

The public response to the finished Spirits Having Flown confirmed all assumptions that it would continue the Bee Gees’ solid platinum success. On March 3, 1979, it became their first number one album (not counting Saturday Night Fever as a composite work) on the Billboard Top 200, where it remained for six weeks, and went on to spend a total of fifty-five weeks on the chart. The Gibbs would also reach another career milestone when Spirits landed at number 9 on Billboard’s Top R&B albums tally. Worldwide, the album is estimated to have sold approximately thirty million copies.

The Bee Gees supported Spirits with a fifty-city North American tour, which began on June 28th, 1979 in Fort Worth, Texas, and concluded in Miami on October 6th. It grossed over $10 million ($37 million in 2019 terms, adjusted for inflation). Perhaps a testament to its rigorous studio arrangements, only two songs from the new album— “Tragedy,” and an acoustic version of “Too Much Heaven”—were included on the set list.

But as the Gibbs contended with becoming one of the biggest bands in the world in an incredibly short timeframe, the physical and emotional toll on them was evident, as they outwardly admitted they were considering what life after the Bee Gees might look like. “We don’t want to be an old group again,” Robin told People in an interview during one of their tour stops in California. “No lasting images, like Nixon standing on the White House lawn with the chopper behind him, waving goodbye. We came into this world to work together, but we can’t be Bee Gees forever. We want to go out on top.”

Four-and-a-half decades later, Spirits Having Flown remains a compelling snapshot of the Gibbs at their zenith, encircled by a pop music kingdom they built by their own talent and innovation. Robin’s statement held some truth. By the end of 1979, the rapidly turning tide of the music industry and the accompanying popular backlash that condemned disco—and the Bee Gees for their implied responsibility for it—implored them to consider other creative options.

The brothers began to work on separate projects for other artists, although they would reassemble at different points to write songs together. Later in the year, Maurice co-produced The Osmonds’ Steppin’ Out with Steve Klein, Robin and Blue Weaver formed a production partnership for R&B legend Jimmy Ruffin’s 1980 album, Sunrise, and Barry, Karl, and Albhy continued with their team approach for Barbra Streisand’s Guilty (1980). The Bee Gees wouldn’t return to the studio as a complete entity until 1981 to record the Living Eyes album.

But in the wider view of the Bee Gees’ lengthy career, Spirits Having Flown reflects more than just the era in which it was recorded. Its ingenuity also embodies the realized dreams of three brothers who dedicated themselves guilelessly to their craft, and to the millions they touched with their music.

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2019 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.