Happy 55th Anniversary to Aretha Franklin’s twelfth studio album Lady Soul, originally released January 22, 1968.

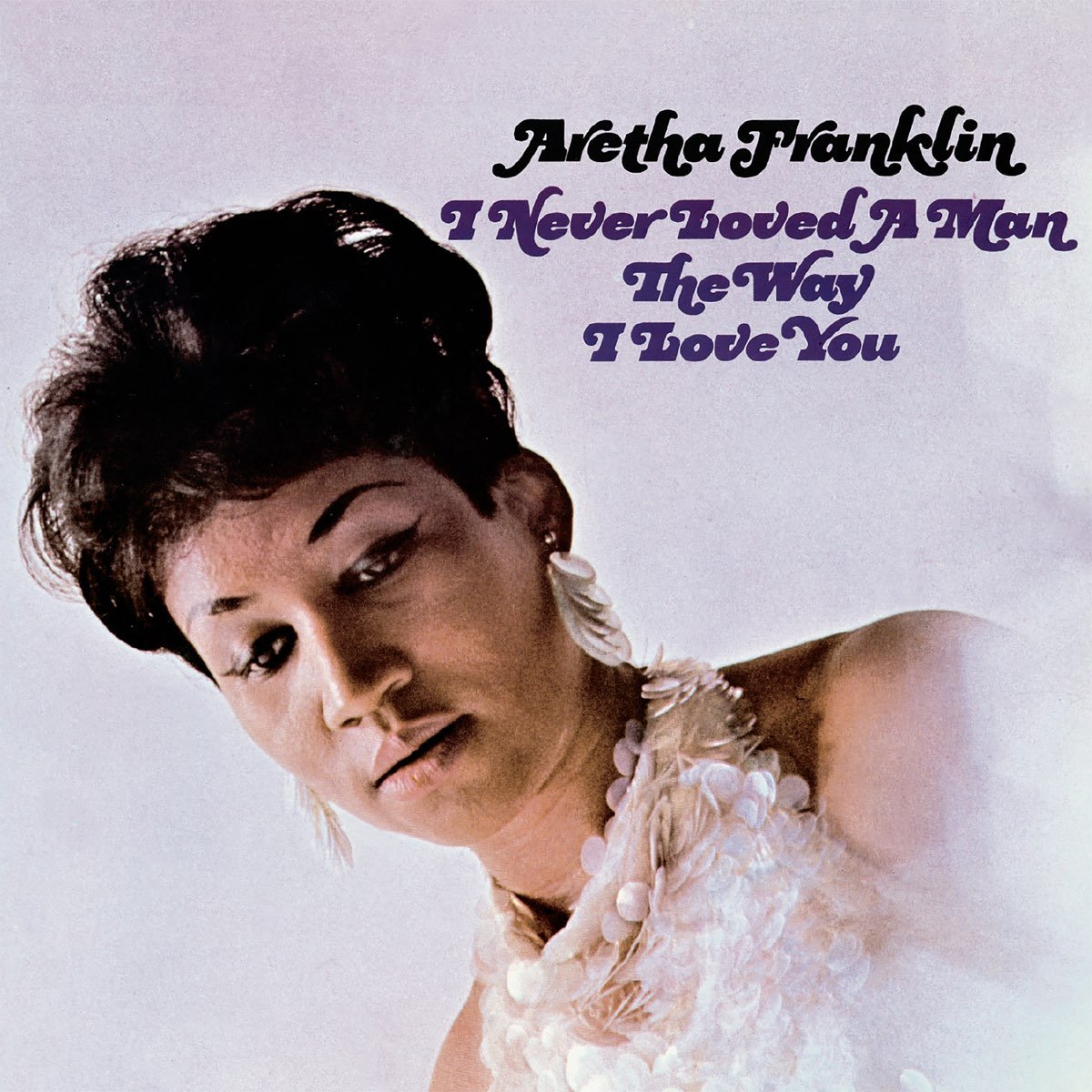

When the final sessions for her third album on Atlantic Records wrapped in mid-December of 1967, Aretha Franklin was relishing the fruits of a breakthrough in her seven-year career as a recording artist. She opened that year with the release of her epoch-making, gold-selling first album recorded for Atlantic, I Never Loved a Man the Way I Love You, spawning classic staples such as the irresistible blues-tinged title track, the ultra-sultry “Dr. Feelgood (Love Is a Serious Business),” the sentimental “Do Right Woman, Do Right Man” and her beloved, political call-to-arms reading of Otis Redding’s “Respect.” Her sophomore Atlantic album, Aretha Arrives, was released in the summer of that year.

A handsomely subdued, yet swanky potpourri of contemporary pop-rock covers, classic standards, and soul-stirring originals, Aretha Arrives garnered lukewarm reception from a record-buying public caught in the fervor of I Never Loved a Man. Nevertheless, the album supplied the then 25-year-old Franklin with her third top-ten hit, as the funky, pop-soul oriented ditty “Baby, I Love You” zoomed up the pop and soul charts later that same summer.

As her career was experiencing a fruitful revamp since capping her six-year tenure at Columbia Records and transitioning to Atlantic in 1966, Franklin had little time to rest on her laurels. Atlantic certainly wasted no time in galvanizing the momentum of her success, sustained across a stretch of eight months. To hold her anxious fan base and public over, the label released singles for “(You Make Me Feel Like) a Natural Woman” and “Chain of Fools” toward the end of 1967. These two singles would set the stage for the eventful release of her third Atlantic offering, 1968’s aptly titled Lady Soul.

The fascinating aspect of Franklin’s enduring artistry was her gift for combining several forms and genres of music into a mightily unified expression of her own emotional resonance and cultural lineage. She never limited herself to a singular style, or settled on sticking to the traditional modes of a musical form. Whether she chose a treasure from the Great American songbook, or ended up conjuring her own material, she uninhibitedly stuck to her own instinct and taste to emote the power of whatever she sang.

As her former mentor and producer Jerry Wexler explained in his 1994 David Ritz-assisted autobiography, Rhythm and the Blues: A Life in American Music: “There are three qualities that make a great singer—head, heart and throat. The head is intelligence, the phrasing. The heart is the emotionality that feeds the flames. The throat is the chops, the voice. Ray Charles certainly has the first two. Aretha, though, like Sam Cooke, has all three.” With one listen to Lady Soul, the rare combination of Franklin’s musical virtuoso, intellect, and feeling is vividly manifested.

Compared to its predecessors, I Never Loved a Man the Way I Love You and Aretha Arrives, Lady Soul is a more refined, yet eclectic rendering of her deep soul underpinning. Her unparalleled blend of hard-edged rural blues with the polished modes of city blues stretches across the album’s ten exquisite selections. Driven by a King Curtis-led horn section, the rhythm backing of the Muscle Shoals delegation and a who’s who roster of all-star musicians, including Joe Smith, Eric Clapton, and a young Bobby Womack, there’s an earthy urgency that runs through the album. Even when it sweetens a bit, it’s still direct. The grooves knock with rock-solid precision. While she will always be credited with infusing her innate gospel sensibilities within hard-hitting R&B, Lady Soul epitomizes the core of Franklin’s idiosyncratic pop mastery: improvising her own personal style of blues to create an emotional space in her music.

Watch the Official Lyric Videos:

When Franklin’s fellow labelmate, R&B singer-songwriter Don Covay penned “Chain of Fools” as a young boy, he was inspired by field hands he saw as a child in South Carolina. Years later, Jerry Wexler requested that he come up with material for Otis Redding. Covay cut a stripped-down, bluesy demo of the song, with his guitar playing and overdubbed lead and background vocal. When he played the demo for Redding in Wexler’s office, Wexler insisted that Covay give it to Franklin. When she heard it, she immediately loved it. Covay slightly reworked the song to fit her, lessening its original blues-flavored intent. The rest was history.

Recorded on June 23, 1967, “Chain of Fools” serves as the powerhouse ignition that sets the tone for Lady Soul, with its country-fried Southern funk and Franklin’s gospel-rooted pop prowess. The song’s seamless cross between pop, rock, and soul music is beautifully triggered by singer-songwriter Joe South’s distinctive, Pops Staples-tinged electric guitar figures throughout the song. His heavy use of vibrato adds a robust, gritty texture to the song’s percussive pulse. Never contrived or mechanical, the lively, harmonic interplay between Franklin, her sisters, Carolyn and Erma Franklin, and the Sweet Inspirations perfectly synchronizes with the relentless funk power. Franklin’s older sister, Erma, flexes her commanding, husky voice, driving the vocal interplay home.

Whereas Convay reflected on the Jim Crow-ridden South, Franklin wailed from the perspective of an agonized black woman, scorned by a lover’s betrayal and heartbreak. Ironically, for those who knew her best, the song’s devastating lyrics alluded to her abusive relationship with then-manager and husband, Ted White. Her sister, Carolyn Franklin once revealed in an interview: “Aretha didn’t write ‘Chain,’ but she might as well have. It was her story. When we were putting on the backgrounds with Ree doing lead, I knew she was singing about Ted.” Furthering the political implications of “Respect,” “Chain of Fools” eventually grew emblematic of the determination, hope, and strength women, freedom fighters, and black vets fighting in the Vietnam War upheld in an era when social unrest and inequality was boiling over.

Centering a timely gaze on black America’s tumultuous challenges and unprecedented promise, Franklin takes on James Brown’s “Money Won’t Change You” and the Impressions’ “People Get Ready.” On “Money Won’t Change You,” Brown spun a funky indictment on the socioeconomic disparities that plague people who are darker than blue, assuring them that dignity and pride could save them from succumbing to their present condition. While Franklin doesn’t alter the tenacity of Brown’s message completely, she breathes a less restrained immediacy into Brown’s kinetic original. Even more amazingly, she flips Brown’s male-centric perspective and positions it onto herself, intersecting the motives of the Civil Rights Movement with women’s active role in it.

An admirer of Curtis Mayfield’s artistry, Franklin douses Baptist fervor into the Impressions’ contemplative call for unity and peace in her version of “People Get Ready.” From the Sweet Inspirations’ angelic opening refrain of “I believe, you know I believe” to its rousing, sanctified conclusion, Aretha underscores the classic’s connection to the gospel vision and black political legacy.

P.J. Proby’s foray into Cajun-flavored patois and hipness led to his biggest American hit with 1967’s “Niki Hoeky.” Franklin morphs the original’s jubilant, blue-eyed soul nuance into a smooth, Memphis-bred, deep soul juggernaut. When she gets wind of the Young Rascals’ unlikely 1967 hit “Groovin’,” the original’s cool allure is retained, with the Sweet Inspirations soulfully intoning the distinctive “Sunday, Sunday” line, in reference to the Mamas and Papas’ signature song “Monday, Monday.”

Enjoying this article? Click/tap on the album covers to explore more about Aretha Franklin:

The Franklin and Ted White composition, “(Sweet Sweet Baby) Since You’ve Been Gone” boisterously prowls with a mighty funk and soul punch, while a hard-rocking take on Ray Charles’ “Come Back Baby” features strong guitar backing from Bobby Womack.

Franklin’s blues bent oozes through the devastating, 12/8-meter after-hours ballad, “Good to Me as I Am to You.” Written entirely by Franklin (Ted White’s co-writing credit was used for unknown legal reasons), the song echoes the empowering sentiment reached in her previous hit “Respect,” depicting a woman’s call for reciprocation of the loyalty and consideration she gives her lover. In the midst of recording Cream’s 1967 sophomore album Disraeli Gears, Eric Clapton was brought into the recording session for the song by his mentor, Ahmet Ertegun. Ertegun encouraged Clapton to lay down his stinging blues licks to augment Franklin’s arresting delivery. It worked flawlessly. Afterwards, Clapton was said to be both intimidated and astonished by her performance.

Producer Jerry Wexler often marveled at Franklin’s inner strength as a woman. He recognized this characteristic as an essential component to her emotional resonance and survival. Using this observation as inspiration, Wexler asked Brill Building stalwarts Carole King and Gerry Goffin to write a song about a “natural woman" for Franklin. They came up with “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman.” A spiritually graceful piece of pop-soul, Franklin tackles the grandiose ballad with her tasteful gospel flair, never allowing the song’s stately pop arrangement to interfere with her unwavering conviction.

Most commonly associate Franklin’s version of “Natural Woman” with its innate intent, citing it as a love song, showcasing a woman devoting her gratitude to a man who has given her a sense of purpose. However, when she sang it, she devoted her love to the Lord. Her masterful phrasing and ability to retain the cascade of varying emotions demanded by the lyrics infuses each line with transcendental potency.

When Carole King recorded her criminally disregarded take for her 1971 landmark LP Tapestry, she stripped the grandeur, revealing pure vulnerability that Franklin’s version doesn’t capture as eloquently. It’s not just in King’s unhurried, fragile delivery that arresting intimacy is found, but the song’s sparse ambiance, in general. Where Franklin relied on scared etherealness to convey emotion, King brought the ballad back to its intended context. Nevertheless, Franklin’s peerless vocal performance may be the only glowing strength that makes her version a beloved standard-bearer in popular music. It remains the centerpiece of Lady Soul.

Although she wasn’t as well-known as her famous older sister, Carolyn Franklin was an accomplished singer and songwriter in her own right. Her church-honed vocal stylings were a prominent mainstay in many of her sister’s hits, but she also penned some of the most hauntingly beautiful work in her vast repertoire. The beauty of Carolyn’s classic ballad, “Ain’t No Way” relies on its heartbreaking pensiveness. Aretha achingly sings of a woman exorcising unnerving agony to her man, declaring that she can’t fully deliver her love and devotion to him in his repugnance toward her. In the midst of Aretha’s sturdy lead, Cissy Houston’s heavenly soprano obbligato creeps into the backdrop, conjuring an otherworldly aura to the somber, torch-like ballad.

Aretha Franklin was inaugurated as “the Queen of Soul” during her sweeping breakthrough of 1967. But, with Lady Soul, she was rightfully sworn into the great company of music royalty. It’s often difficult to rank Franklin’s mountainous peaks and target the one that encapsulates the summit of her artistry. There are way too many in her illustrious, seven-decade career. Lady Soul stands as the most important one that towers above her vast repertoire—a virtual masterpiece that places her shape-shifting virtuosity, political prowess, and womanism in the greatest, widest context possible.

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2018 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.