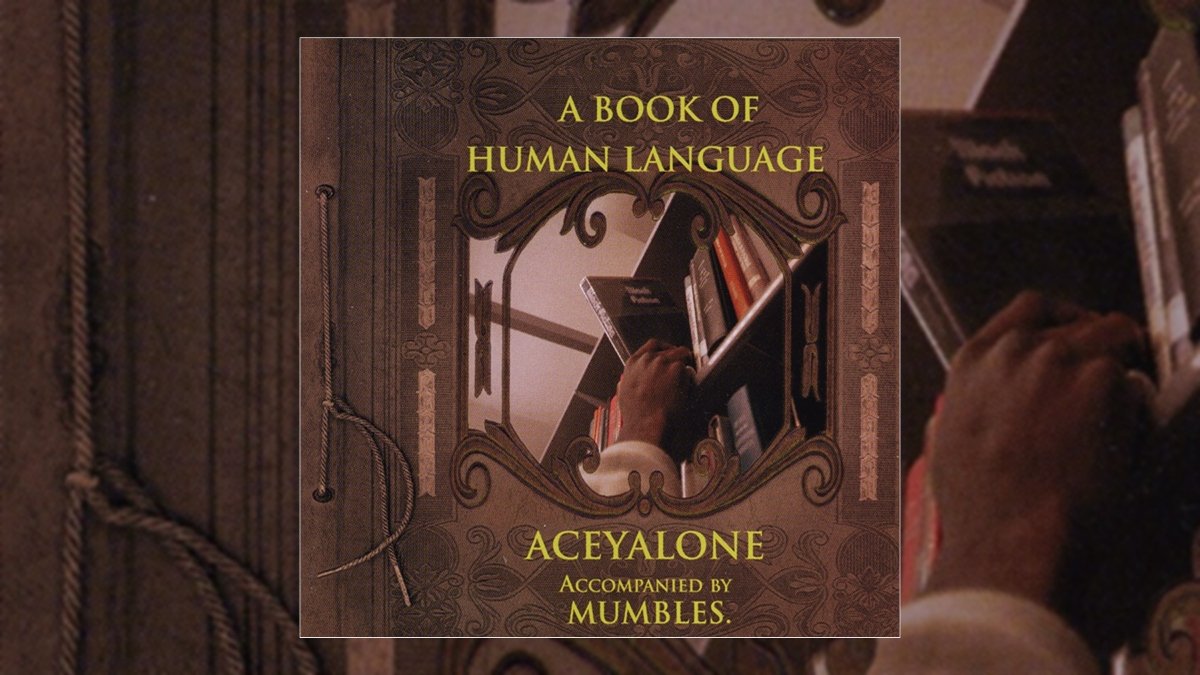

Happy 25th Anniversary to Aceyalone’s second studio album A Book of Human Language, originally released April 14, 1998

Hip-Hop is often an exercise in the micro over the macro. Most artists express themselves by creating raps that relate to their own personal circumstances. Sometimes they’ll tie their rhymes into larger societal problems, but if they do, they let the listener connect the appropriate dots.

The philosophical ambition of Aceyalone’s A Book of Human Language is part of what makes it distinctive. Released 25 years ago, it’s an album that explores big ideas and concepts. Much as the title of the album suggests, it’s literary in its execution, with each song serving as a “chapter” in the project’s overall story. It’s the strongest of Aceyalone’s solo albums and one of the best overall albums that he’s contributed to.

Edwin “Aceyalone” Hayes, Jr. was first known as a member of the Freestyle Fellowship crew, a pioneering group of legendary lyricists from Los Angeles. As a member of the Fellowship and the Project Blowed collective, Aceyalone had already proven himself as one of the foremost lyrical talents in hip-hop, mastering verbal gymnastics and executing complicated flows, styles, cadences and off-the-head techniques. By showing that he could skillfully shift gears to addressing big concepts, he further established his emcee pedigree.

Just as integral to the album’s success is Matthew “Mumbles” Fowler. Aceyalone first worked with the Bay Area-born producer on his first solo album, All Balls Don’t Bounce (1995). Mumbles was the musical creative force behind two of the album’s most memorable songs: “Greatest Show On Earth” and “Makeba.” Acey chose to have Mumbles behind the boards for the entirety of Human Language and it pays off. Mumbles created the beats mostly using rough-and-tumble jazz samples, layering them into a complex soundtrack to accompany Acey’s deep thoughts. The result makes A Book of Human Language one of the most outstanding one emcee/one producer collaborations in the history of hip-hop.

Aceyalone begins the album with “The Guidelines,” previously known as “Guidelines ’94,” a hold-over from the All Balls recording sessions. Despite its origins, the song naturally fits into the scheme of the album sonically and thematically. Acey explains how he works to redefine the rules and break the barriers of what’s considered acceptable in his approach to hip-hop music, because “I’d rather stimulate your mind than emulate your purpose / And we have only touched on the surface of the serpent.”

On tracks like “The Balance” and “The Hold,” Aceyalone is able to expound on concepts like finding balance in life and learning how to let go without sounding didactic or even overtly sentimental. “The Energy” is the album’s most fast-paced and briefest full song, a swift consideration on how the power of maintaining a positive outlook can conquer negative circumstances. “I said it hurts so good but it’s…not pain,” he raps. “Just the electric charge coming from the mainframe / And my main aim to dig through the dirt, stay alert / Insert the power cord so my energy will work.”

Listen to the Album:

Aceyalone’s way with words and complex rhyming styles allows him to delve into broad topics in a unique manner. On “The Faces,” he considers how physical appearance shapes human interaction and our perceptions of each other. Meanwhile, “The Walls & Windows” is a nearly six-minute song literally dedicated to the power and significance that walls and windows hold. The beat is Mumbles’ oddest creation for the album, filled with warped horns, chimes, and rattling percussion. It was originally an instrumental track called “At the Mountains of Madness” released on the Deep Concentration (1997) compilation. Yet Aceyalone’s exceptional delivery makes for an ideal marriage to the eccentric track.

Spoken word poetry remains a large component of A Book of Human Language. Often tracks end with extended poetic codas, and Acey incorporates other pieces as stand-alone tracks, such as “The Vision,” which examines the power of inspiration. As a whole, the spoken word pieces often function as the connective tissue and bridges from track to track. And really, only Aceyalone could incorporate an a cappella reading (through heavy vocal distortion) of “The Jabberwocky,” as in Lewis Carroll’s masterpiece of a nonsense poem from Through the Looking Glass, into the flow of the album.

At times Aceyalone explores the poverty that permeates the neighborhoods where he was raised. On “The Hurt,” he describes the pain that he feels when he observes the crime-ravaged communities that surround him. He hopes that his fellow residents will be able to rise up from these dire circumstances, but fears the worst, rapping, “But who am I to tell on who will prevail / And who's gonna fail and who in the hell / Are you going to tell? You’re new to the trail / You’re doomed to sail away.”

“The March” serves as a brief inspirational counterpoint to “The Hurt.” Here Aceyalone acknowledges the difficult environment where he was raised, and pledges to “refuse to be abused.” The ethereal guitar and bass-heavy track makes the song and Acey’s vocal performance nearly shimmer.

“The Grandfather Clock,” a meditation on the relentless nature of time, is the album’s peak. Mumbles outdoes himself, creating a pulsing, methodical drum track and bassline that of course sound very much like components of the nominal clock. Meanwhile, percussion and other haunting sounds filter in and out, giving the song an eerie feel. For his part, Aceyalone examines the exorable determination of time’s passage, even rhyming from the perspective of the clock and time itself, reminding the listener that “If you ever race against me, you will surely come up short."

“The Thief in the Night” explores similar themes, more specifically the inevitably and unpredictability of death. For this track, Mumbles creates a decidedly somber tone, building a track from mournful flute samples and melancholy chimes. The content itself is fittingly morbid, as Aceyalone reflects that death’s arrival is inevitable, and no matter how you prepare yourself, it often strikes when least expected.

The album’s last full-track is “Human Language,” Acey’s dedication to the power of words, language, and ideas. It’s also probably his best overall performance on the album. Mumbles sets the mood for the lyrical presentation, sampling “Lonely Woman” by jazz legend Ornette Coleman. The resonant, oddly tempo-ed bassline is ideal for Acey’s unorthodox flows, verbal construction, and rhyme schemes, as a flute echoes in the background. In the midst of explaining how he works to cultivate new ways of thinking, he expertly explains his pedigree: “Scientifically ain’t no ripping me, I’m terrifically well-spoken / See many attempts to get a glimpse to see what the hell I'm smoking / But it ain’t no ’bamma, I just mastered this bastard grammar / I go outside my parameter and stretch out my diameter It gets bigger than Gamera / So picture that with your camera.”

Aceyalone has continued to record music over the last quarter-century, mostly as a solo artist, occasionally as a member of a group (either Freestyle Fellowship or Haiku D’Etat). However, this was one of Mumbles’ last production releases; he’s released music only sparingly since A Book of Human Language’s release. It’s a shame the pair never worked together again, because their compelling collaboration resulted in the type of album that most artists would not deign to try. We should consider ourselves fortunate that these two decided to execute this ambitious undertaking, while further demonstrating hip-hop’s literary merit.

LISTEN:

Editor's note: this anniversary tribute was originally published in 2018 and has since been edited for accuracy and timeliness.