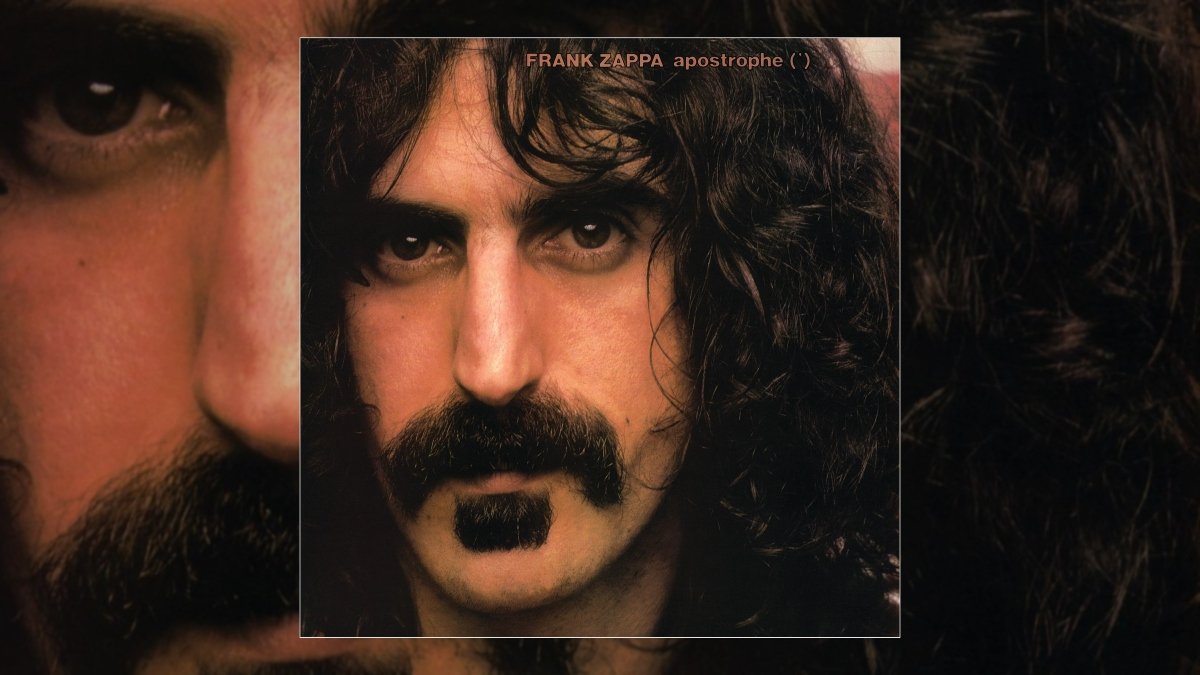

Happy 50th Anniversary to Frank Zappa’s eighteenth studio album Apostrophe (‘), originally released March 22, 1974.

Frank Zappa possessed a genius that I don’t fully understand. The guitarist/composer/arranger seemingly spoke his own unique musical language whenever he recorded, and it’s one I feel that I can hardly wrap my brain around at times. During his life, Zappa was especially prolific, recording and releasing dozens of albums while alive, and dozens more posthumously. When approaching his music, I feel similar to when I try to explore the works of other eccentric departed geniuses like Sun-Ra or Lee “Scratch” Perry: it’s a daunting endeavor, for which I feel like I’m barely scratching the surface of what Zappa has to offer.

All that said, I do know that I love Apostrophe (’), Zappa’s eighteenth album, released 50 years ago. I feel a little strange that I’ve gravitated to his most commercially successful (it was certified Gold by the RIAA and made the Billboard Top 10), since, as a listener, I try to seek out the road less travelled. That being said, Apostrophe (’) certainly doesn’t present a compromised or watered-down version of Zappa. It’s every bit as weird and experimental as many of the entries in his discography.

Apostrophe (’) came on the heels of Over-Nite Sensation (1973), which is considered Zappa’s break-out record. Over-Nite was not well-received critically; the subject matter of many of the songs is sex, which Zappa covered in a tongue-in-cheek, yet juvenile way. Even though Apostrophe (’) is mostly devoid of sexual content and innuendo, it is not a course correction; Zappa tended not to give a shit about what the critics thought of his music.

Apostrophe (’) isn’t any less juvenile as Over-Nite or many of his other albums. However, it’s juvenile in a hilarious and infectious way. The musicianship is impressively expert, blending many musical genres and taking risks that many musicians wouldn’t hazard to attempt. Zappa also possessed a strong anti-authoritarian streak, which manifests itself in different ways throughout Apostrophe (’).

A central component to Zappa’s music is what he termed “Protect/Object” or “conceptual continuity.” Songs on his album frequently segue together seamlessly, flowing effortlessly from track to track. However, he also saw each one of his albums as tied to something larger, an oeuvre where musical ideas and characters would appear throughout many of the projects. It’s a technique that he uses throughout Apostrophe (’). Reportedly the first half of Apostrophe (’) was recorded at the same time as Over-Nite Sensation, while many of the other tracks came from various sessions in the preceding years. Zappa pieces everything together in a way so that everything feels vital and current, no matter when it was actually recorded.

Listen to the Album:

Much of Apostrophe (’)’s legend is built on its extended opening, often referred to as the “Nanook” suite, a four-part goofily surreal undertaking. The premise, in true Zappa fashion, is ridiculous: he describes a dream where, as Nanook the Eskimo, he engages in unorthodox combat at the North Pole with a nefarious fur trapper who is accosting a baby seal. It would be enough if the suite just gave us the classic line, “Watch out where the huskies go and don’t you eat that yellow snow,” but the suite’s first half details the use of lead-filled snowshoes and weaponized urine-soaked snow. The musical backdrop shifts constantly, from prog rock to slinky soul to experimentations in jazz.

Musically, Zappa picks up the pace during the suite’s second half, as the blinded fur-trapper stumbles across the tundra, only to discover a Catholic parish in the midst of serving the world’s sleaziest pancake breakfast. “St. Alfonzo’s Pancake Breakfast” and “Father O’Blivion” each feel like dance tracks, as he layers xylophones with triumphant horn blasts with high tempo guitar work. Over six-and-a-half minutes, Zappa continues to pile on over-the-top imagery, from sausage patty abuse to margarine thievery to a priest’s surreptitious sexual relationships with a Leprechaun, all held together by the celebration of the light and fluffy pancakes.

Apostrophe (’)’s appeal doesn’t rely on the Nanook Suite alone. Zappa uses the Blues-drenched “Cosmik Debris” to air grievances, in particular his deep dislike of gurus, mystics, and various other new age hucksters. Some of the humor is recycled (or subject to conceptual continuity); the line “Is that a real poncho or a Sears poncho” appeared on Over-Nite Sensation. However, so help me, I find the puerile line “The price of meat has just gone up and your old lady has just gone down” to be funny as hell.

Apostrophe (’)’s other centerpiece is the title track. It’s a lengthy instrumental jam featuring Zappa on guitar, session drummer Jim Gordon on drums, and possibly Jack Bruce on the bass. Though the Cream bassist is listed in the album’s liner notes and Zappa has described the session, Bruce has been a little cagey in interviews about what, exactly, he contributed to the song. Regardless, the track is a guitar-driven epic that sounds like something that could have easily appeared on a late 1960s Jimi Hendrix album.

“Uncle Remus” is the album’s best individual achievement. Co-written with keyboardist George Duke, it’s a bittersweet and borderline satirical look at the status of the Civil Rights movement in the mid-1970s. Zappa takes the perspective of the African American protesters, increasingly frustrated at how even in the 1970s, the United States had to be dragged kicking and screaming into recognizing the rights of its Black population. He also touches on respectability politics on the gospel-influenced track, as he sings, “We look pretty sharp in these clothes / Unless we get sprayed with a hose.” Zappa still keeps the fighting spirit alive, as he promises to “take a drive to Beverly Hills just before dawn / And knock the little jockeys off the rich people’s lawn.”

Though Apostrophe (’) was Zappa’s most popular album, it did successfully encapsulate everything that made him great as a musician. Few musicians contrasted “low” subject matter with “high” musical art like him. And even though I still feel a little intimated by the volume of his discography, I respect that he was a fearless iconoclast whose subversive proclivities made him a one-in-a-billion type of artist. Even if I’m still just scratching the surface, I’m blown away by what he had to offer.

Listen: